Granulocyte

Granulocytes are a category of white blood cells in the innate immune system characterized by the presence of specific granules in their cytoplasm.[1] They are also called polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN, PML, or PMNL) because of the varying shape of the nucleus, which is usually lobed into three segments. This distinguishes them from the mononuclear agranulocytes. The term polymorphonuclear leukocyte often refers specifically to "neutrophil granulocytes",[2] the most abundant of the granulocytes; the other types (eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells) have lower numbers of lobes. Granulocytes are produced via granulopoiesis in the bone marrow.

| Granulocyte | |

|---|---|

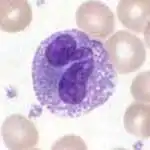

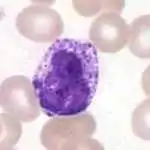

A basophilic granulocyte. | |

| Details | |

| System | Immune system |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D006098 |

| FMA | 62854 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Types

There are four types of granulocytes (full name polymorphonuclear granulocytes):[3]

Except for the mast cells, their names are derived from their staining characteristics; for example, the most abundant granulocyte is the neutrophil granulocyte, which has neutrally staining cytoplasmic granules.

Neutrophils

Neutrophils are normally found in the bloodstream and are the most abundant type of phagocyte, constituting 60% to 65% of the total circulating white blood cells,[4] and consisting of two subpopulations: neutrophil-killers and neutrophil-cagers. One litre of human blood contains about five billion (5x109) neutrophils,[5] which are about 12–15 micrometres in diameter.[6] Once neutrophils have received the appropriate signals, it takes them about thirty minutes to leave the blood and reach the site of an infection.[7] Neutrophils do not return to the blood; they turn into pus cells and die.[7] Mature neutrophils are smaller than monocytes, and have a segmented nucleus with several sections(two to five segments); each section is connected by chromatin filaments. Neutrophils do not normally exit the bone marrow until maturity, but during an infection neutrophil precursors called myelocytes and promyelocytes are released.[8]

Neutrophils have three strategies for directly attacking micro-organisms: phagocytosis (ingestion), release of soluble anti-microbials (including granule proteins), and generation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).[9] Neutrophils are professional phagocytes:[10] they are ferocious eaters and rapidly engulf invaders coated with antibodies and complement, as well as damaged cells or cellular debris. The intracellular granules of the human neutrophil have long been recognized for their protein-destroying and bactericidal properties.[11] Neutrophils can secrete products that stimulate monocytes and macrophages; these secretions increase phagocytosis and the formation of reactive oxygen compounds involved in intracellular killing.[12]

Neutrophils have two types of granules; primary (azurophilic) granules (found in young cells) and secondary (specific) granules (which are found in more mature cells). Primary granules contain cationic proteins and defensins that are used to kill bacteria, proteolytic enzymes and cathepsin G to break down (bacterial) proteins, lysozyme to break down bacterial cell walls, and myeloperoxidase (used to generate toxic bacteria-killing substances).[13] In addition, secretions from the primary granules of neutrophils stimulate the phagocytosis of IgG antibody-coated bacteria.[14] The secondary granules contain compounds that are involved in the formation of toxic oxygen compounds, lysozyme, and lactoferrin (used to take essential iron from bacteria).[13] Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) comprise a web of fibers composed of chromatin and serine proteases that trap and kill microbes extracellularly. Trapping of bacteria is a particularly important role for NETs in sepsis, where NET are formed within blood vessels.[15]

Eosinophils

Eosinophils also have kidney-shaped lobed nuclei (two to four lobes). The number of granules in an eosinophil can vary because they have a tendency to degranulate while in the blood stream.[16] Eosinophils play a crucial part in the killing of parasites (e.g., enteric nematodes) because their granules contain a unique, toxic basic protein and cationic protein (e.g., cathepsin[13]);[17] receptors that bind to IgE are used to help with this task.[18] These cells also have a limited ability to participate in phagocytosis,[19] they are professional antigen-presenting cells, they regulate other immune cell functions (e.g., CD4+ T cell, dendritic cell, B cell, mast cell, neutrophil, and basophil functions),[20] they are involved in the destruction of tumor cells,[16] and they promote the repair of damaged tissue.[21] A polypeptide called interleukin-5 interacts with eosinophils and causes them to grow and differentiate; this polypeptide is produced by basophils and by T-helper 2 cells (TH2).[17]

Basophils

Basophils are one of the least abundant cells in bone marrow and blood (occurring at less than two percent of all cells). Like neutrophils and eosinophils, they have lobed nuclei; however, they have only two lobes, and the chromatin filaments that connect them are not very visible. Basophils have receptors that can bind to IgE, IgG, complement, and histamine. The cytoplasm of basophils contains a varied amount of granules; these granules are usually numerous enough to partially conceal the nucleus. Granule contents of basophils are abundant with histamine, heparin, chondroitin sulfate, peroxidase, platelet-activating factor, and other substances.

When an infection occurs, mature basophils will be released from the bone marrow and travel to the site of infection.[22] When basophils are injured, they will release histamine, which contributes to the inflammatory response that helps fight invading organisms. Histamine causes dilation and increased permeability of capillaries close to the basophil. Injured basophils and other leukocytes will release another substance called prostaglandins that contributes to an increased blood flow to the site of infection. Both of these mechanisms allow blood-clotting elements to be delivered to the infected area (this begins the recovery process and blocks the travel of microbes to other parts of the body). Increased permeability of the inflamed tissue also allows for more phagocyte migration to the site of infection so that they can consume microbes.[19]

Mast cells

Mast cells are a type of granulocyte that are present in tissues;[3] they mediate host defense against pathogens (e.g., parasites) and allergic reactions, particularly anaphylaxis.[3] Mast cells are also involved in mediating inflammation and autoimmunity as well as mediating and regulating neuroimmune system responses.[3][23][24]

Development

Granulocytes are derived from stem cells residing in the bone marrow. The differentiation of these stem cells from pluripotent hematopoietic stem cell into granulocytes is termed granulopoiesis. Multiple intermediate cell types exist in this differentiation process, including myeloblasts and promyelocytes.

Function

Granule contents

Examples of toxic materials produced or released by degranulation by granulocytes on the ingestion of microorganisms are:

- Antimicrobial agents (Defensins and Eosinophil cationic protein)

- Enzymes

- Acid hydrolases: further digest bacteria

- Lysozyme: dissolves cell walls of some gram-positive bacteria

- Low pH vesicles (3.5-4.0)

- Toxic nitrogen oxides (nitric oxide)

- Toxic oxygen-derived products (e.g., superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxy radicals, singlet oxygen, hypohalite)

Clinical significance

Granulocytopenia is an abnormally low concentration of granulocytes in the blood. This condition reduces the body's resistance to many infections. Closely related terms include agranulocytosis (etymologically, "no granulocytes at all"; clinically, granulocyte levels less than 5% of normal) and neutropenia (deficiency of neutrophil granulocytes). Granulocytes live only one to two days in circulation (four days in spleen or other tissue), so transfusion of granulocytes as a therapeutic strategy would confer a very short-lasting benefit. In addition, there are many complications associated with such a procedure.

There is usually a granulocyte chemotactic defect in individuals suffering from type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Research suggests giving granulocyte transfusions to prevent infections decreased the number of people who had a bacterial or fungal infection in the blood.[25] Further research suggests participants receiving therapeutic granulocyte transfusions show no difference in clinical reversal of concurrent infection.[26]

Additional images

_diagram_en.svg.png.webp) Hematopoiesis

Hematopoiesis

See also

References

- WebMD (2009). "granulocyte". Webster's New World Medical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-544-18897-6.

- WebMD (2009). "leukocyte, polymorphonuclear". Webster's New World Medical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-544-18897-6.

- Breedveld A, Groot Kormelink T, van Egmond M, de Jong EC (October 2017). "Granulocytes as modulators of dendritic cell function". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 102 (4): 1003–1016. doi:10.1189/jlb.4MR0217-048RR. PMID 28642280.

- Stvrtinová, Viera; Ján Jakubovský and Ivan Hulín (1995). "Neutrophils, central cells in acute inflammation". Inflammation and Fever from Pathophysiology: Principles of Disease. Computing Centre, Slovak Academy of Sciences: Academic Electronic Press. ISBN 80-967366-1-2. Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved March 28, 2009.

- Hoffbrand p. 331

- Abbas, Chapter 12, 5th Edition

- Sompayrac p. 18

- Linderkamp O, Ruef P, Brenner B, Gulbins E, Lang F (December 1998). "Passive deformability of mature, immature, and active neutrophils in healthy and septicemic neonates". Pediatric Research. 44 (6): 946–50. doi:10.1203/00006450-199812000-00021. PMID 9853933.

- Hickey MJ, Kubes P (May 2009). "Intravascular immunity: the host-pathogen encounter in blood vessels". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 9 (5): 364–75. doi:10.1038/nri2532. PMID 19390567.

- Robinson p. 187 and Ernst pp. 7–10

- Paoletti p. 62

- Soehnlein O, Kenne E, Rotzius P, Eriksson EE, Lindbom L (January 2008). "Neutrophil secretion products regulate anti-bacterial activity in monocytes and macrophages". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 151 (1): 139–45. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03532.x. PMC 2276935. PMID 17991288.

- Mayer, Gene (2006). "Immunology — Chapter One: Innate (non-specific) Immunity". Microbiology and Immunology On-Line Textbook. USC School of Medicine. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- Soehnlein O, Kai-Larsen Y, Frithiof R, Sorensen OE, Kenne E, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, et al. (October 2008). "Neutrophil primary granule proteins HBP and HNP1-3 boost bacterial phagocytosis by human and murine macrophages". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 118 (10): 3491–502. doi:10.1172/JCI35740. PMC 2532980. PMID 18787642.

- Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, McDonald B, Goodarzi Z, Kelly MM, et al. (April 2007). "Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood". Nature Medicine. 13 (4): 463–9. doi:10.1038/nm1565. PMID 17384648.

- Hess CE. "Segmented Eosinophil". University of Virginia Health System. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- Baron, Samuel (editor) (1996). Medical Microbiology (4th edition). EditionThe University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Gleich GJ, Adolphson CR (1986). "The Eosinophilic Leukocyte: Structure and Function". Advances in Immunology Volume 39. Advances in Immunology. 39. pp. 177–253. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60351-X. ISBN 978-0-12-022439-5.

- Campbell p. 903

- Akuthota P, Wang HB, Spencer LA, Weller PF (August 2008). "Immunoregulatory roles of eosinophils: a new look at a familiar cell". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 38 (8): 1254–63. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03037.x. PMC 2735457. PMID 18727793.

- Kariyawasam HH, Robinson DS (April 2006). "The eosinophil: the cell and its weapons, the cytokines, its locations". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 27 (2): 117–27. doi:10.1055/s-2006-939514. PMID 16612762.

- Hess CE. "Mature Basophil". University of Virginia Health System. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- Lee DM, Friend DS, Gurish MF, Benoist C, Mathis D, Brenner MB (September 2002). "Mast cells: a cellular link between autoantibodies and inflammatory arthritis". Science. 297 (5587): 1689–92. doi:10.1126/science.1073176. PMID 12215644.

- Polyzoidis S, Koletsa T, Panagiotidou S, Ashkan K, Theoharides TC (September 2015). "Mast cells in meningiomas and brain inflammation". Journal of Neuroinflammation. 12 (1): 170. doi:10.1186/s12974-015-0388-3. PMC 4573939. PMID 26377554.

MCs originate from a bone marrow progenitor and subsequently develop different phenotype characteristics locally in tissues. Their range of functions is wide and includes participation in allergic reactions, innate and adaptive immunity, inflammation, and autoimmunity [34]. In the human brain, MCs can be located in various areas, such as the pituitary stalk, the pineal gland, the area postrema, the choroid plexus, thalamus, hypothalamus, and the median eminence [35]. In the meninges, they are found within the dural layer in association with vessels and terminals of meningeal nociceptors [36]. MCs have a distinct feature compared to other hematopoietic cells in that they reside in the brain [37]. MCs contain numerous granules and secrete an abundance of prestored mediators such as corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), neurotensin (NT), substance P (SP), tryptase, chymase, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), TNF, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and varieties of chemokines and cytokines some of which are known to disrupt the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [38–40].

They key role of MCs in inflammation [34] and in the disruption of the BBB [41–43] suggests areas of importance for novel therapy research. Increasing evidence also indicates that MCs participate in neuroinflammation directly [44–46] and through microglia stimulation [47], contributing to the pathogenesis of such conditions such as headaches, [48] autism [49], and chronic fatigue syndrome [50]. In fact, a recent review indicated that peripheral inflammatory stimuli can cause microglia activation [51], thus possibly involving MCs outside the brain. - Estcourt LJ, Stanworth S, Doree C, Blanco P, Hopewell S, Trivella M, Massey E (June 2015). "Granulocyte transfusions for preventing infections in people with neutropenia or neutrophil dysfunction". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD005341. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005341.pub3. PMC 4538863. PMID 26118415.

- Estcourt LJ, Stanworth SJ, Hopewell S, Doree C, Trivella M, Massey E (April 2016). "Granulocyte transfusions for treating infections in people with neutropenia or neutrophil dysfunction". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD005339. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005339.pub2. PMC 4930145. PMID 27128488.

Bibliography

- Campbell NA, Reece JB (2002). Biology (6th ed.). Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8053-6624-2.

- Delves PJ, Martin SJ, Burton DR, Roit IM (2006). Roitt's Essential Immunology (11th ed.). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-3603-7.

- Ernst JD, Stendahl O (2006). Phagocytosis of Bacteria and Bacterial Pathogenicity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84569-6.

- Hoffbrand AV, Pettit JE, Moss PA (2005). Essential Haematology (4th ed.). Blackwell Science. ISBN 978-0-632-05153-3.

- Paoletti R, Notario A, Ricevuti G, eds. (1997). Phagocytes: Biology, Physiology, Pathology, and Pharmacotherapeutics. The New York Academy of Sciences. ISBN 978-1-57331-102-1.

- Robinson JP, Babcock GF, eds. (1998). Phagocyte Function —A guide for research and clinical evaluation. Wiley–Liss. ISBN 978-0-471-12364-4.

- Sompayrac L (2008). How the Immune System Works (3rd ed.). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-6221-0.

External links

Media related to Granulozyt at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Granulozyt at Wikimedia Commons