Chaco Province

Chaco (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈtʃako]; Wichi: To-kós-wet[3]), officially the Province of Chaco (Spanish: provincia del Chaco, Spanish pronunciation: [pɾo'βinsja dεl ˈtʃako]), is one of the 23 provinces in Argentina. Its capital and largest city, is Resistencia.[4] It is located in the north-east of the country.

Chaco

Provincia del Chaco | |

|---|---|

| Province of Chaco | |

Palm trees in Resistencia City | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

.svg.png.webp) Location of Chaco within Argentina | |

| Country | |

| Official Languages | Spanish, Kom, Moqoit and Wichí |

| Capital and largest city | Resistencia |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Jorge Capitanich (PJ) |

| • Deputies | 7 |

| • Senators | María Inés Pilatti Vergara Antonio José Rodas Víctor Zimmermann |

| Area | |

| • Total | 99,633 km2 (38,469 sq mi) |

| Population (2010)[1] | |

| • Total | 1,055,259 |

| • Rank | 10th |

| • Density | 11/km2 (27/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Chacoan, chaqueño |

| Time zone | UTC−3 (ART) |

| ISO 3166 code | AR-H |

| HDI (2018) | 0.806 Very High (24th)[2] |

| Website | www |

It is bordered by Salta and Santiago del Estero to the west, Formosa to the north, Corrientes to the east, and Santa Fe to the south.[4] It also has an international border with the Paraguayan Department of Ñeembucú. With an area of 99,633 km2 (38,469 sq mi), and a population of 1,055,259 as of 2010, it is the twelfth most extensive, and the ninth most populated, of the twenty-three Argentine provinces.

In 2010, Chaco became the second province in Argentina to adopt more than one official language. These languages are the Kom, Moqoit and Wichí languages, spoken by the Toba, Mocovi and Wichí peoples respectively. Chaco has historically been among Argentina's poorest regions, and currently ranks last both by per capita GDP and on the Human Development Index.

Etymology

Chaco derives from chacú, the Quechua word used to name a hunting territory or the hunting technique used by the people of the Inca Empire.

Annually, large groups of up to thirty thousand hunters would enter the territory, forming columns and circling their prey.[5] Jesuit missioner Pedro Lozano wrote in his book Chorographic Description of the Great Chaco Gualamba, published in Cordoba, Spain in 1733: "Its etymology indicates the multitude of nations that inhabit that region. When they go hunting, the Indians gather from many parts the vicuñas and guanacos; that crowd is called chacu in the Quechua language, which is common in Peru, and that Spaniards have corrupted into Chaco".[6]

However, the earliest known mention of the term in a document was in a letter written to Fernando Torres de Portugal y Mesía, Viceroy of Peru, dated in 1589, by the then Governor of Tucumán, Juan Ramírez de Velasco, who referred to the region as Chaco Gualamba.[7] (The term Gualamba is of uncertain origin and has since fallen into disuse.[7])

Geography

The province of Chaco lies within the southern part of the Gran Chaco region, a vast lowland plain that covers territories in Argentina, Paraguay, and Bolivia.

Chaco Province covers an area of 99,633 km2 (38,469 sq mi) and ranks as the twelfth largest Argentinian province. The highest ground in the province is also the most western, near the municipality of Taco Pozo, at an elevation of 272 m (892 ft) above sea level.[8]

The Paraná and Paraguay rivers separate Chaco province from Corrientes Province and the Republic of Paraguay. To the north, the river Bermejo forms another natural border, dividing Chaco Province from Formosa Province.

In the south, the border follows the 28th parallel south, separating the region from Santa Fe Province, while in the west it borders Salta and Santiago del Estero.

Other important rivers include: the Negro, Tapenagá, Palometa, and Salado, all tributaries or anabranches of the river Paraná.

Climate

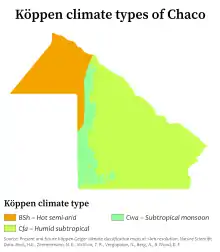

The province has a subtropical climate.[9] It is divided in two different climate zones: a more humid one in the east and a drier subtropical climate in the center and west.[10] The eastern parts of the province have a humid subtropical climate (Cfa under the Köppen climate classification) with no dry season.[11] In the west where precipitation is lower, it has a subtropical climate with a dry winter and is classified as a semi-arid climate (BS under the Köppen climate classification) due to potential evapotranspiration exceeding precipitation.[11]

Precipitation

In the most humid (eastern) parts of the province, precipitation falls throughout the year with no dry season.[11] These areas receive around 1,400 millimetres (55 in) of precipitation per year.[11] Precipitation decreases westwards and become more concentrated in the summer months.[9][11]

Temperature

Mean annual temperatures range between 21 to 23 °C (70 to 73 °F) which decreases from north to south.[11] Summers are hot with temperatures that can reach up to 38 to 41 °C (100 to 106 °F) in the eastern parts of the province.[11] The western parts experience more variation in temperatures due continental influences;[9] extreme temperatures in summer are more extreme with temperatures that frequently exceed 40 °C (104 °F).[11] During winters, incursions of cold, polar air from the south can lead to frosts and temperatures that fall below freezing.[11] Being under an area of high solar radiation during summer, a consequence is that a low pressure system forms over the province during summer.[11]

Humidity

Humidity in the province is high due to its climate, particularly in the north, the wettest portion of the province.[11] Most of the winds that transport humid air come from the north and east.[11] Winters are the most humid seasons (high humidity) due to this season being characterized by frequent fogs.[11]

History

The area was originally inhabited by various hunter-gatherers speaking languages from the Mataco-Guaicru family. Native tribes including the Toba, and Wichí survive in the region and have important communities in this province as well as in Formosa Province.

In 1576, the governor of a province in Northern Argentina commissioned the military to search for a huge mass of iron, which he had heard that natives used for their weapons. The natives called the area Heavenly Fields, which was translated into Spanish as Campo del Cielo. This area is now a protected region situated on the border between the provinces of Chaco and Santiago del Estero where a group of iron meteorites fell in a Holocene impact event some four to five thousand years ago. In 2015, Police arrested four alleged smugglers trying to steal over a ton of legally protected meteoric iron.[12]

The first European settlement was founded by Spanish conquistador Alonso de Vera y Aragón, in 1585, and was called Concepción de Nuestra Señora. It was abandoned in 1632. During its existence, it was one of the most important cities in the region, but attacks from local Indians forced the residents to leave. In the 17th century, the San Fernando del Río Negro Jesuit mission was founded in the area of the modern-day city of Resistencia, but it was abandoned fifteen years later.

The Gran Chaco region remained largely unexplored, and uninhabited, by either Europeans or Argentines until the late 19th century, after numerous confrontations between Argentina and Paraguay during the War of the Triple Alliance. San Fernando was re-established as a military outpost, and was renamed Resistencia in 1876.

The Territorio Nacional del Gran Chaco was established in 1872. This territory, which included the current Formosa Province and lands presently inside Paraguay, was superseded by Territorio Nacional del Chaco upon its administrative division, in 1884.

20th century

Between the end of the nineteenth and the first decades of the twentieth centuries, the province received a variety of immigrants, among them Volga Germans and Mennonites from Russia, Germany, and Canada. They, alongside other immigrants, transformed Chaco into a productive farming region known for its dairy and beef production.

Political structure

In 1951 the territory became a province, and its name was changed to Provincia Presidente Perón. The province was renamed again in 1955 when the government of President Juan Perón was overthrown, returning to the historical name of Chaco. Chaco voters, however, continued to support Peronist candidates in subsequent elections, notably Deolindo Bittel whose three terms as governor in the 1960s and 1970s were each cut short by military intervention. Bitell subsequently ran for vice-president in the 1983 Argentine Presidential elections and later served as mayor of the provincial capital, Resistencia.

Infrastructure

With few paved highways, and thus an overdependence on passenger rail services, Chaco was adversely impacted by the national rail privatizations and line closures of the early 1990s. In 1997, the services that had been previously run by the state-owned company Ferrocarriles Argentinos since railway nationalization in 1948, were taken over by the Servicios Ferroviarios del Chaco S.A. (SEFECHA) (Chaco Railway Services), making SEFECHA, at the time, the only publicly owned commuter rail service in Argentina. SEFECHA currently carries nearly a million passengers a year and has contributed to the province's vigorous recovery from the 2002 crisis.[13]

Poverty

Chaco Province continues to suffer from the worst social indicators in the country with 49.3% of its population living below the poverty line by income and with 17.5% of children between the ages of two and five in a state of malnutrition in 2009.[14] Among Argentine provinces, it ranks last by GDP per capita and 21st by Human Development Index, only above its neighbors Formosa and Santiago del Estero.

Economy

Chaco's economy, like most in the region, is relatively underdeveloped, yet has recovered vigorously since 2002. It was estimated to be US$4.397 billion in 2006, or US$4,467 per capita (half the national average and the third-lowest in Argentina).[17] Chaco's economy is diversified, but its agricultural sector has suffered from recurrent droughts over the past decade.

Agricultural development in Chaco is predominantly associated with the commercial growing of quebracho wood and cotton. Chaco currently produces 60% of Argentina's national cotton production. Agricultural food production accounts for 17% of Argentina's output. This includes crops such as soy, sorghum, and maize. Sugarcane is also cultivated in the south, as well as rice and tobacco to a lesser degree.

Cattle breeds consisting of crosses with zebu are regarded as better adapted to the high temperatures, grass shortage and occasional flooding than intensively reared pure-breeds.

Industrial contributes approximately 10% to the provincial economy and includes textiles produced from local cotton, oil and coal production, and sugar, alcohol and paper, all derived from sugar cane.

Chaco is home to the Chaco National Park, but tourism is not a well-developed industry in the province. The province's main airport, Resistencia International Airport, serves around 100,000 passengers annually.

Government

The provincial government is divided into the usual three branches: the executive, headed by a popularly elected governor, who appoint the cabinet; the legislative; and the judiciary, headed by the Supreme Court and completed by several inferior tribunals.

The Constitution of Chaco Province forms the formal law of the province.

In Argentina, the most important law enforcement organization is the Argentine Federal Police but the additional work is carried out by the Chaco Provincial Police.

Political organization

The province is divided into 25 departments (Spanish: departamentos).

| Department | Seat | Area (km2) |

Population (2010)[18] |

Population (2001)[18] |

Density (2010) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almirante Brown | Pampa del Infierno | 17,276 | 34,075 | 29,086 | 1.97 |

| Bermejo | La Leonesa | 2,562 | 25,052 | 24,215 | 9.77 |

| Chacabuco | Charata | 1,378 | 30,590 | 27,813 | 22.19 |

| Comandante Fernández | Presidencia Roque Sáenz Peña | 1,500 | 96,944 | 88,164 | 64.63 |

| 12 de Octubre | General Pinedo | 2,576 | 22,281 | 20,149 | 8.65 |

| 2 de Abril | Hermoso Campo | 1,594 | 7,432 | 7,435 | 4.66 |

| Fray Justo Santa María del Oro | Santa Sylvina | 2,205 | 11,826 | 10,485 | 5.36 |

| General Belgrano | Corzuela | 1,218 | 11,988 | 10,470 | 9.84 |

| General Donovan | Makallé | 1,487 | 13,490 | 13,385 | 9.07 |

| General Güemes | Juan José Castelli | 25,487 | 67,132 | 62,227 | 2.63 |

| Independencia | Campo Largo | 1,871 | 22,411 | 20,620 | 11.98 |

| Libertad | Puerto Tirol | 1,088 | 12,158 | 10,822 | 11.17 |

| Libertador General San Martín | General José de San Martín | 7,800 | 59,147 | 54,470 | 7.58 |

| Maipú | Tres Isletas | 2,855 | 25,288 | 24,747 | 8.85 |

| Mayor Luis J. Fontana | Villa Ángela | 3,708 | 55,080 | 53,550 | 14.85 |

| 9 de Julio | Las Breñas | 2,097 | 28,555 | 26,955 | 13.61 |

| O'Higgins | San Bernardo | 1,580 | 20,131 | 19,231 | 12.74 |

| Presidencia de la Plaza | Presidencia de la Plaza | 2,284 | 12,499 | 12,231 | 5.47 |

| Primero de Mayo | Margarita Belén | 1,864 | 10,322 | 9,131 | 5.53 |

| Quitilipi | Quitilipi | 1,545 | 34,081 | 32,083 | 22.05 |

| San Fernando | Resistencia | 3,489 | 390,874 | 365,637 | 112.03 |

| San Lorenzo | Villa Berthet | 2,135 | 14,702 | 14,252 | 6.88 |

| Sargento Cabral | Colonia Elisa | 1,651 | 15,899 | 15,030 | 9.63 |

| Tapenagá | Charadai | 6,025 | 4,097 | 4,188 | 0.68 |

| 25 de Mayo | Machagai | 2,358 | 29,215 | 28,070 | 12.39 |

References

- "República Argentina por provincia o jurisdicción". Censo 2010. INDEC. 28 February 2012. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- "Información para el desarrollo sostenible: Argentina y la Agenda 2030" (PDF) (in Spanish). United Nations Development Programme. p. 155. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- "Lengua Wichi (Mataco). Diccionario Mataco - Español". pueblosoriginarios.com. Retrieved Oct 4, 2020.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 786.

- "Chaco". Fundación para el Desarrollo Sustentable del Chaco. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- Lozano, Pedro (1989). Descripción corográfica del Gran Chaco Gualamba. San Miguel de Tucumán: Universidad Nacional de Tucumán. p. 486.

- Edelmiro Porcel. "Chaco Gualamba". Periodico Domine. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- "23 Cumbres - Chaco". 23 Cumbres. Archived from the original on 24 September 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- "El cultivo del algodón en la cuenca media del Tapenaga. Fechas de siembra, rendimiento y precipitaciones" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional del Nordeste. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- "Provincia de Chaco" (PDF) (in Spanish). Administración Nacional de Laboratorios e Institutos de Salud. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- "Provincia de Chaco–Clima y Meteorologia" (in Spanish). Secretaria de Mineria de la Nacion (Argentina). Archived from the original on 13 September 2004. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- "Four arrested in Argentina smuggling more than ton of meteorites". news.yahoo.com. Retrieved Oct 4, 2020.

- "Argentinien - Friends of Latin American Railways". www.ferrolatino.ch. Retrieved Oct 4, 2020.

- "Capitanich admitió que Chaco tiene los peores indicadores sociales de la Argentina pero culpó a la Nación". infobae.com. 26 July 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- Ley No. 5598 de la Provincia de Corrientes, 22 de octubre de 2004

- Ley No. 6604 de la Provincia de Chaco, 28 de julio de 2010, B.O., (9092), Link Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "El déficit consolidado de las provincias rondará los $11.500 millones este año" (in Spanish). Instituto Argentino para el Desarrollo de las Economías Regionales. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "Cuadro P1-P. Provincia del Chaco. Población total y variación intercensal absoluta y relativa por departamento" (PDF). INDEC. 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

External links

Media related to Chaco Province at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chaco Province at Wikimedia Commons- Official website (Spanish)

- Pictures of Chaco