Code of Hammurabi

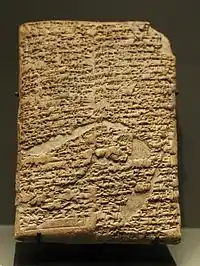

The Code of Hammurabi is a well-preserved Babylonian code of law of ancient Mesopotamia, dated to about 1754 BC (Middle Chronology). It is one of the oldest deciphered writings of significant length in the world. The sixth Babylonian king, Hammurabi, enacted the code. A partial copy exists on a 2.25-metre-tall (7.4 ft) stone stele. It consists of 282 laws, with scaled punishments, adjusting "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth" (lex talionis)[1] as graded based on social stratification depending on social status and gender, of slave versus free, man versus woman.[2]

| Code of Hammurabi | |

|---|---|

A side view of the stele "fingertip" at the Louvre Museum | |

| Created | c. 1754 BC |

| Author(s) | Hammurabi |

Nearly half of the code deals with matters of contract, establishing the wages to be paid to an ox driver or a surgeon for example. Other provisions set the terms of a transaction, the liability of a builder for a house that collapses, or property that is damaged while left in the care of another. A third of the code addresses issues concerning household and family relationships such as inheritance, divorce, paternity, and reproductive behavior. Only one provision appears to impose obligations on a government official; this provision establishes that a judge who alters his decision after it is written down is to be fined and removed from the bench permanently.[3] A few provisions address issues related to military service.

The code was discovered by modern archaeologists in 1901, and its editio princeps translation published in 1902 by Jean-Vincent Scheil. This nearly complete example of the code is carved into a diorite stele[4] in the shape of a huge index finger,[5] 2.25 m (7.4 ft) tall. The code is inscribed in the Akkadian language using cuneiform script. The material was imported into Sumeria from Magan - today the area covered by the United Arab Emirates and Oman.[6]

It is currently on display in the Louvre, with replicas in numerous institutions. These include: the Headquarters of the United Nations in New York City, Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law in Chicago, the Clendening History of Medicine Library & Museum at the University of Kansas Medical Center, the library of the Theological University of the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands, the Pergamon Museum of Berlin, the Arts Faculty of the University of Leuven in Belgium, the National Museum of Iran in Tehran, the Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, the University Museum at the University of Pennsylvania, the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Russia, the Prewitt-Allen Archaeological Museum at Corban University, Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, and the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

History

Hammurabi ruled from 1792 to 1750 BC (according to the middle chronology). At the head of the stone slab is Hammurabi receiving the law from Shamash,[7] and in the preface, he states, "Anu and Bel called by name me, Hammurabi, the exalted prince, who feared God, to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil-doers; so that the strong should not harm the weak; so that I should rule over the black-headed people like Shamash, and enlighten the land, to further the well-being of mankind."[8] The laws were arranged in 44 columns and 28 paragraphs; some follow along the rules of "an eye for an eye".[9]

It was taken as plunder by the Elamite king Shutruk-Nahhunte in the 12th century BC and was taken to Susa in Elam (located in the present-day Khuzestan Province of Iran), where it was no longer available to the Babylonian people. However, when Cyrus the Great brought both Babylon and Susa under the rule of his Persian Empire and placed copies of the document in the Library of Sippar, the text became available for all the peoples of the vast Persian Empire to view.[10]

In 1901, Egyptologist Gustave Jéquier, a member of an expedition headed by Jacques de Morgan, found the stele containing the Code of Hammurabi during archaeological excavations at the ancient site of Susa in Khuzestan.[11]

The stele unearthed in 1901 had many laws scraped off by Shutruk-Naknunte. Early estimates pegged the number of missing laws at 34, however the exact number is still not determined and only 30 have been discovered so far. The common belief is that the code contained 282 laws in total.[12]

Laws of Hammurabi's Code

.jpg.webp)

The Code of Hammurabi was one of the only sets of laws in the ancient Near East and also one of the first forms of law.[13] The code of laws was arranged in orderly groups, so that all who read the laws would know what was required of them.[14] Earlier collections of laws include the Code of Ur-Nammu, king of Ur (c. 2050 BC), the Laws of Eshnunna (c. 1930 BC) and the codex of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin (c. 1870 BC), while later ones include the Hittite laws, the Assyrian laws, and Mosaic Law.[15] These codes originate from similar cultures in a relatively small geographical area, and they have passages that resemble each other.[16]

The Code of Hammurabi is the longest surviving text from the Old Babylonian period.[17] The code has been seen as an early example of a fundamental law, regulating a government – i.e., a primitive constitution.[18][19] The code is also one of the earliest examples of the idea of presumption of innocence, and it also suggests that both the accused and accuser have the opportunity to provide evidence.[20] The occasional nature of many provisions suggests that the code may be better understood as a codification of Hammurabi's supplementary judicial decisions, and that, by memorializing his wisdom and justice, its purpose may have been the self-glorification of Hammurabi rather than a modern legal code or constitution. However, its copying in subsequent generations indicates that it was used as a model of legal and judicial reasoning.[21]

While the Code of Hammurabi was trying to achieve equality, biases still existed against those categorized in the lower end of the social spectrum and some of the punishments and justice could be gruesome. The magnitude of criminal penalties often was based on the identity and gender of both the person committing the crime and the victim. The Code issues justice following the three classes of Babylonian society: property owners, freed men, and slaves.[22]

Punishments for someone assaulting someone from a lower class were far lighter than if they had assaulted someone of equal or higher status.[22] For example, if a doctor killed a rich patient, he would have his hands cut off, but if he killed a slave, only financial restitution was required.[23] Women could also receive punishments that their male counterparts would not, as men were permitted to have affairs with their servants and slaves, whereas married women would be harshly punished for committing adultery.[22]

Other copies

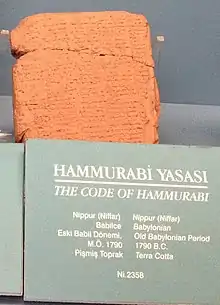

Various copies of portions of the Code of Hammurabi have been found on baked clay tablets, some possibly older than the celebrated basalt stele now in the Louvre. The Prologue of the Code of Hammurabi (the first 305 inscribed squares on the stele) is on such a tablet, also at the Louvre (Inv #AO 10237). Some gaps in the list of benefits bestowed on cities recently annexed by Hammurabi may imply that it is older than the famous stele (currently dated to the early 18th century BC).[24] Likewise, the Museum of the Ancient Orient, part of the Istanbul Archaeology Museums, also has a "Code of Hammurabi" clay tablet, dated to 1790 BC (in Room 5, Inv # Ni 2358).[25][26]

In July 2010, archaeologists reported that a fragmentary Akkadian cuneiform tablet was discovered at Tel Hazor, Israel, containing a c. 1700 BC text that was said to be partly parallel to portions of the Hammurabi code. The Hazor law code fragments are currently being prepared for publication by a team from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[27]

Laws covered

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

Today, approximately 282 laws from Hammurabi's Code are known. Each law is written in two parts: A specific situation or case is outlined, then a corresponding decision is given.[28]

One of the best known laws from Hammurabi's code was:

Ex. Law #196: "If a man destroy the eye of another man, they shall destroy his eye. If one break a man's bone, they shall break his bone. If one destroy the eye of a freeman or break the bone of a freeman he shall pay one gold mina. If one destroy the eye of a man's slave or break a bone of a man's slave he shall pay one-half his price."[29]

Hammurabi had many other punishments, as well. If a son strikes his father, his hands shall be hewn off. Translations vary.[30][31]

The laws covered such subjects as:

- Slander

- Ex. Law #127: "If any one 'point the finger' at a sister of a god or the wife of any one, and can not prove it, this man shall be taken before the judges and his brow shall be marked (by cutting the skin, or perhaps hair)."[29]

- Fraud

- Ex. Law #265: "If a herdsman, to whose care cattle or sheep have been entrusted, be guilty of fraud and make false returns of the natural increase, or sell them for money, then shall he be convicted and pay the owner ten times the loss."[29]

- Slavery and status of slaves as property

- Ex. Law #15: "If any one take a male or female slave of the court, or a male or female slave of a freed man, outside the city gates, he shall be put to death."[29]

- The duties of workers

- Ex. Law #42: "If any one take over a field to till it, and obtain no harvest therefrom, it must be proved that he did no work on the field, and he must deliver grain, just as his neighbor raised, to the owner of the field."[29]

- Theft

- Ex. Law #22: "If any one is committing a robbery and is caught, then he shall be put to death."[29]

- Trade

- Ex. Law #104: "If a merchant give an agent grain, wool, oil, or any other goods to transport, the agent shall give a receipt for the amount, and compensate the merchant therefore, he shall obtain a receipt from the merchant for the money that he gives the merchant."[29]

- Liability

- Ex. Law #53: "If any one be too apathetic to keep his dam in primly condition, and does not so keep it; if then the dam break and all the fields be flooded, then shall he in whose dam the break occurred be sold for money, and the money shall replace the crops which he has caused to be ruined."[29]

- Divorce

- Ex. Law #142: "If a woman quarrel with her husband, and say: "You are not congenial to me," the reasons for her prejudice must be presented. If she is guiltless, and there is no fault on her part, but he leaves and neglects her, then no guilt attaches to this woman, she shall take her dowry and go back to her father's house."[29]

- Adultery

- Ex. Law #129: "If the wife of a man has been caught lying with another man, they shall bind them and throw them into the waters. If the owner of the wife would save his wife then in turn the king could save his servant."[32]

- Perjury

- Ex. Law #3: "If a man has borne false witness in a trial, or has not established the statement that he has made, if that case be a capital trial, that man shall be put to death."[29]

See also

- Code of the Assura

- Cuneiform Law

- Hippocratic Oath

- List of ancient legal codes

- Quid pro quo

- Urukagina – Sumerian king and creator of what is sometimes cited as the first example of a legal code in recorded history

Footnotes

- Prince, J. Dyneley (July 1904). "The Code of Hammurabi". The American Journal of Theology. The University of Chicago Press. 8 (3): 601–609. doi:10.1086/478479. JSTOR 3153895.

- Gabriele Bartz & Eberhard König, Arts and Architecture—Louvre, (Köln: Könemann, 2005), ISBN 978-3-8331-1943-9. The laws were based with scaled punishments, adjusting "an eye for an eye" depending on social status and gender.

- Code of Hammurabi Archived 21 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine at commonlaw.com Code of Hammarubi at Commonlaw, 22 May 2017

- Moorey, P. R. S. (Peter Roger Stuart), 1937- (1999). Ancient mesopotamian materials and industries : the archaeological evidence. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns. p. 29. ISBN 1575060426. OCLC 42907384.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Iconographic Evidence for Some Mesopotamian Cult Statues, Dominique Collon, Die Welt der Götterbilder, Edited by Groneberg, Brigitte; Spieckermann, Hermann;, and Weiershäuser, Frauke, Berlin, New York (Walter de Gruyter) 2007, pp. 57–84

- RAGOZIN, ZENAIDE A. (2017). STORY OF CHALDEA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO THE RISE OF ASSYRIA : treated as a general ... introduction to the study of ancient history. [Place of publication not identified]: FORGOTTEN Books. p. 209. ISBN 978-1330342589. OCLC 990104817.

- Wells, H. G. (1961). The Outline of History: Volume 1. Doubleday. p. 176.

- Edited by Richard Hooker; Translated by L.W King (1996). "Mesopotamia: The Code of Hammurabi". Washington State University. Archived from the original on 9 September 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Hammurabi's Code" "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), Think Quest, retrieved on 2 Nov 2011.

- Marc Van De Mieroop: A History of the Ancient Near East, second edition p. 296

- Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2013. ISBN 9781588394750. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- "The Discovery of Hammurabi's Code" "The PLEA: Hammurabi's Code". Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- L.W. King (2005). "The Code of Hammurabi: Translated by L.W. King". Yale University. Archived from the original on 16 September 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- "The Code of Hammurabi: Introduction," , Ancient History Sourcebook, March 1998, retrieved on 2 November 2011.

- Barton, G.A: Archaeology and the Bible. University of Michigan Library, 2009, (originally published in 1916 by American Sunday-School Union) p. 406.

- Barton 2009, p. 406. Barton, a scientist of Semitic languages at the University of Pennsylvania from 1922 to 1931, stated that while there are similarities between the Mosaic Law and the Code of Hammurabi, a study of the entirety of both laws "convinces the student that the laws of the Old Testament are in no essential way dependent upon the Babylonian laws." He states that "such resemblances" arose from "a similarity of antecedents and of general intellectual outlook" between the two cultures, but that "the striking differences show that there was no direct borrowing."

- "The Code of Hammurabi," , The History Guide, 3 August 2009, Retrieved on 2 November 2011.

- What is a Constitution? William David Thomas, Gareth Stevens (2008) p. 8

- Flach, Jacques. Le Code de Hammourabi et la constitution originaire de la propriete dans l'ancienne Chaldee. (Revue historique. Paris, 1907. 8. v. 94, pp. 272–289.

- Victimology: Theories and Applications, Ann Wolbert Burgess, Albert R. Roberts, Cheryl Regehr, Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2009, p. 103

- For this alternative interpretation see Jean Bottéro, "The 'Code' of Hammurabi" in Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning and the Gods (University of Chicago, 1992), pp. 156–184.

- "8 Things You May Not Know About Hammurabi's Code". History.com. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- "What was Babylon?". History Extra. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- Fant, Clyde E. and Mitchell G. Reddish (2008), Lost Treasures of the Bible: Understanding the Bible Through Archaeological Artifacts in World Museums, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., p. 62.

- Freely, John, Blue Guide Istanbul (5th ed., 2000), London: A&C Black, New York: WW Norton, p. 121. ("The most historic of the inscriptions here [i.e., Room 5, Museum of the Ancient Orient, Istanbul] is the famous Code of Hammurabi (#Ni 2358) dated 1750 BC, the world's oldest recorded set of laws.")

- Museum of the Ancient Orient website Archived 3 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine ("This museum contains a rich collection of ancient ... archaeological finds, including ... seals from Nippur and a copy of the Code of Hammurabi.")

- "Code of Hammurabi Tablet Found". Inside Israel News – Arutz Sheva.

- "From the Laws of Hammurabi's Code" "The PLEA: Hammurabi's Code". Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "The Code of Hammurabi". Internet Sacred Text Archive. Evinity Publishing. 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Translated by L.W. King, Hammurabi's Code of Laws, Hammurabi's Code of Laws Archived 9 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Translated by L.W. King, Hammurabi's Code of Laws, The Code of Hammurabi King of Babylon by Robert Francis Harper (PDF)

- C. Sax, Benjamin (2001). Western Civilization Volume 1: From the Origins of Civilization to the Age of Absolutism. San Diego: Greenhaven Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-56510-988-9.

References

- Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black, Larry S. Krieger, Phillip C. Naylor, Dahia Ibo Shabaka (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Luttrell. ISBN 978-0-395-87274-1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Bonhomme, Brian, and Cathleen Boivin. "Code of Hammurabi." Milestone Documents in World History. Exploring the Primary Sources That Shaped the World: 2350 BCE – 1058 CE. Vol. 1. Dallas, TX: Schlager Group, 2010. 23–31.

- Bryant, Tamera (2005). The Life & Times of Hammurabi. Bear: Mitchell Lane Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58415-338-2.

- Driver, G.R.; J.C. Miles (2007). The Babylonian Laws. Eugene: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-55635-229-4.

- Elsen-Novák, G./Novák, M.: Der 'König der Gerechtigkeit'. Zur Ikonologie und Teleologie des 'Codex' Hammurapi. In: Baghdader Mitteilungen 37 (2006), pp. 131–156.

- Falkenstein, A. (1956–57). Die neusumerischen Gerichtsurkunden I–III. München.

- Febbraro, Flavio, and Burkhard Schwetje. How to Read World History in Art. New York: Abrams, 2010. Print.

- Hammurabi, King; C. H. W. Johns (Translator) (2000). The Oldest Code of Laws in the World. City: Lawbook Exchange Ltd. ISBN 978-1-58477-061-9.

- Mieroop, Marc (2004). King Hammurabi of Babylon: a Biography. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4051-2660-1.

- Julius Oppert and Joachim Menant (1877). Documents juridiques de l'Assyrie et de la Chaldee. París.

- Roth, Martha T. (1997). Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. Atlanta: Scholars Press. ISBN 978-0-7885-0378-8.

- Public Legal Education Association of Saskatchewan. (2016) Hammurabi's Code, The PLEA, Vol. 36, No. 2.

- Editio princeps: Scheil, Jean-Vincent (1902). "Code des Lois de Hammurabi". Memoires de la delegation en Perse. 4 (Textes Elamites-Semitiques). Paris P. Geuthner [etc.]

- Thomas, D. Winton, ed. (1958). Documents from Old Testament Times. London and New York.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Look up Hammurabi in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The Laws of Hammurapi, Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative

- The Code of Hammurabi Translated by L. W. King.

- Law Code of Hammurabi, king of Babylon | Musée du Louvre

- The Code of Hammurabi: A King with Rules

- The Code of Hammurabi (Harper translation) at Wikisource

- Hammurabi's Code, Blaise Joseph, Clio History Journal, 2009.