The Wedding at Cana

The Wedding Feast at Cana (Italian: Nozze di Cana) (1563), by Paolo Veronese (1528–1588), is a representational painting that depicts the biblical story of the Marriage at Cana, at which Jesus converts water to wine (John 2:1–11). Executed in the Mannerist style (1520–1600) of the late Renaissance, the large-format (6.77m × 9.94m) oil painting comprehends the stylistic ideal of compositional harmony, as practised by the artists Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo.[1]:318

| The Wedding Feast at Cana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Paolo Veronese |

| Year | 1563 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 6.77 m × 9.94 m (267 in × 391 in) |

| Location | Louvre Museum |

The art of the High Renaissance (1490–1527) emphasized human figures of ideal proportions, balanced composition, and beauty, whereas Mannerism exaggerated the Renaissance ideals — of figure, light, and colour — with asymmetric and unnaturally elegant arrangements achieved by flattening the pictorial space and distorting the human figure as an ideal preconception of the subject, rather than as a realistic representation.[1]:469

The visual tension among the elements of the picture and the thematic instability among the human figures in The Wedding Feast at Cana derive from Veronese's application of technical artifice, the inclusion of sophisticated cultural codes and symbolism (social, religious, theologic), which present a biblical story relevant to the Renaissance viewer and to the contemporary viewer.[2] The pictorial area (67.29 m2) of the canvas makes The Wedding Feast at Cana the most expansive picture in the paintings collection of the Musée du Louvre.

History

The commission

.jpg.webp)

At Venice, on 6 June 1562, the Black Monks of the Order of Saint Benedict (OSB) commissioned Paolo Veronese to realise a monumental painting (6.77 m × 9.94 m) to decorate the far wall of the monastery's new refectory, designed by the architect Andrea Palladio, at the Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore, on the eponymous island. In their business contract for the commission of The Wedding Feast at Cana, the Benedictine monks stipulated that Veronese be paid 324 ducats; be paid the costs of his personal and domestic maintenance; be provided a barrel of wine; and be fed in the refectory.[3]

Aesthetically, the Benedictine contract stipulated that the painter represent “the history of the banquet of Christ’s miracle at Cana, in Galilee, creating the number of [human] figures that can be fully accommodated”,[4] and that he use optimi colori (optimal colours) — specifically, the colour ultramarine, a deep-blue pigment made from lapis lazuli, a semi-precious, metamorphic rock.[5] Assisted by his brother, Benedetto Caliari, Veronese delivered the completed painting in September 1563, in time for the Festa della Madonna della Salute, in November.[3]

Composition and technique

In the 17th century, during the mid–1630s, supporters of Andrea Sacchi (1599–1661) and supporters of Pietro da Cortona (1596–1669) argued much about the ideal number of human figures for a representational composition.[6] Sacchi said that only a few figures (fewer than twelve) permit the artist to honestly depict the unique body poses and facial expressions that communicate character; while da Cortona said that many human figures consolidate the general image of a painting into an epic subject from which sub-themes would develop.[6] In the 18th century, in Seven Discourses on Art (1769–90), the portraitist Joshua Reynolds (1723–92), said that:

The subjects of the Venetian painters are mostly such as gave them an opportunity of introducing a great number of figures, such as feasts, marriages, and processions, public martyrdoms, or miracles. I can easily conceive that [Paolo] Veronese, if he were asked, would say that no subject was proper for an historical picture, but such as admitted at least forty figures; for in a less number, he would assert, there could be no opportunity of the painter's showing his art in composition, his dexterity of managing and disposing the masses of light, and groups of figures, and of introducing a variety of Eastern dresses and characters in their rich stuffs.[7]

As a narrative painting in the Mannerist style, The Wedding Feast at Cana combines stylistic and pictorial elements from the Venetian school's philosophy of colorito (priority of colour) of Titian (1488–1576) to the compositional disegno (drawing) of the High Renaissance (1490–1527) used in the works of Leonardo (1452–1519), Raphael (1483–1520), and Michelangelo (1475–1564).[8] As such, Veronese's depiction of the crowded banquet-scene that is The Wedding Feast at Cana is meant to be viewed upwards, from below — because the painting's bottom-edge was 2.50 metres from the refectory floor, behind and above the head-table seat of the abbot of the monastery.[4]

As stipulated in the Benedictine contract for the painting, the canvas of monumental dimensions (6.77m x 9.94m) and area (67.29m2) was to occupy the entire display-wall in the refectory. In the 16th century, Palladio's great-scale design was Classically austere; the monastery dining-room featured a vestibule with a large door, and then stairs that led to a narrow ante-chamber, where the entry door to the refectory was flanked with two marble lavabos, for diners to cleanse themselves;[9] the interior of the refectory featured barrel vaults and groin vaults, rectangular windows, and a cornice.[9] In practise, Veronese's artistic prowess with perspective and architecture (actual and virtual) persuaded the viewer to see The Wedding Feast at Cana as a spatial extension of the refectory.[9][10]

The subject

In The Wedding Feast at Cana (1563), Paolo Veronese depicts the New Testament story of the Marriage at Cana within the historical context of the Renaissance in the 16th century. In the Gospel of John, the story of the first Christian miracle, Mary, her son, Jesus of Nazareth, and some of his Apostles, attend a wedding in Cana, a city in Galilee. In the course of the wedding banquet, the supply of wine was depleted; at Mary's request, Jesus commanded the house servants to fill stone jugs with water, which he then transformed into wine (John 2:1–11).

The banquet

The Wedding Feast at Cana represents the water-into-wine miracle of Jesus in the grand style of the sumptuous feasts of food and music that were characteristic of 16th-century Venetian society;[3] the sacred in and among the profane world where “banquet dishes not only signify wealth, power, and sophistication, but transfer those properties directly into the individual diner. An exquisite dish makes the eater exquisite.”[11]

_-_WGA24859.jpg.webp)

The banquet scene is framed with Greek and Roman architecture from Classical Antiquity and from the Renaissance, Veronese's contemporary era. The Græco–Roman architecture features Doric order and Corinthian order columns surrounding a courtyard that is enclosed with a low balustrade; in the distance, beyond the courtyard, there is an arcaded tower, by the architect Andrea Palladio. In the foreground, musicians play stringed instruments of the Late–Renaissance, such as the lute, the violone, and the viola da gamba.[8]

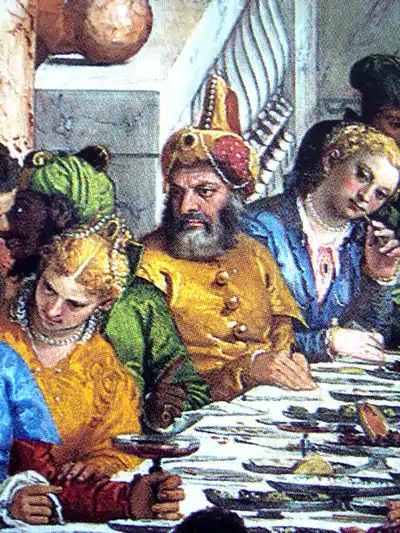

Among the wedding guests are historical personages, such as the monarchs Eleanor of Austria, Francis I of France, and Mary I of England, Suleiman the Magnificent, tenth sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V; the poetess Vittoria Colonna, the diplomat Marcantonio Barbaro, and the architect Daniele Barbaro; the noblewoman Giulia Gonzaga and Cardinal Pole, the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury, the master jester Triboulet and the Ottoman statesman Sokollu Mehmet Paşa — all dressed in the sumptuous Occidental and Oriental fashions alla Turca popular in the Renaissance.[8]

According to 18th-century legend and artistic tradition, the painter of the picture (Paolo Veronese) included himself to the banquet scene, as the musician in white tunic, who is playing a viola da braccio. Accompanying Veronese are the principal painters of the Venetian school: Jacopo Bassano, playing the cornetto, Tintoretto, also playing a viola da braccio, and Titian, dressed in red, playing the violone; besides them stands the poet Pietro Aretino considering a glass of the new red wine.[3][12] A more recent study links the identity of the performer seated behind Veronese playing viola da gamba with Diego Ortiz, musical theorist and then chapell master at the court of Naples.[13]

Symbolism

The Wedding Feast at Cana (1563) is a painting of the Early Modern period; the religious and theological narrative of Veronese's interpretation of the water-into-wine miracle is in two parts.[10]

I. On the horizontal axis — the lower-half of the painting contains 130 human figures; the upper-half of the painting is dominated by a cloudy sky and Geæco–Roman architecture, which frames and contains the historical figures and Late-Renaissance personages invited to celebrate the bride and bridegroom at their wedding feast.[3] Some human figures are rendered in foreshortened perspective, the stylisation of Mannerism; the old architecture mirrors the contemporary architecture of Andrea Palladio; the narrative treatment places the religious subject in a cosmopolitan tableau of historical and contemporary personages, most of whom are fashionably dressed in costumes from the Orient — Asia as known to Renaissance society in the 16th century.[8]

Seated behind and above the musicians are the Virgin Mary, Jesus of Nazareth, and some of his Apostles. Above the figure of Jesus, on an elevated walkway, a man watches the banquet, and a serving maid awaits for the carver to carve an animal to portions. To the right, a porter arrives with more meat for the feasting diners to eat. The alignment of the Jesus figure under the carver's blade and block, and the butchered animals, prefigure his sacrifice as the Lamb of God.[3]

bottom-right-quarter — a barefoot wine-servant pours the new, red wine into a serving ewer, from a large, ornate oenochoe, which earlier had been filled with water. Behind the wine servant stands the poet Pietro Aretino, intently considering the red wine in his glass.[3]

bottom-left-quarter — the steward of the house (dressed in green) supervises the black servant-boy proffering a glass of the new, red wine to the bridegroom, the host of the wedding feast; at the edge of the nuptial table, a dwarf holds a bright-green parrot, and awaits instructions from the house steward.

II. On the vertical axis — the contrasts of light and shadow symbolize the co-existence of mortality and vanitas, the transitory pleasures of earthly life; the protocol of religious symbolism supersedes the social protocol.

In the wedding banquet proper, the holy guests and the mortal hosts have exchanged their social status, and so Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and some of his Apostles, are seated in the place of honour of the centre-span of the banquet table, whilst the bride and bridegroom sit, as guests, at the far end of the table's right wing. Above the Jesus figure, a carver is carving a lamb, beneath the Jesus figure, musicians play lively music, yet, before them is an hourglass — a reference to the futility of human vanity.[8] Moreover, despite the kitchen's continuing preparation of roasted meat, the main course of a celebratory meal, the wedding guests are eating the dessert course, which includes fruit and nuts, wine and sweet quince cheese (symbolically edible marriage); that contradiction, between kitchen and diners, indicates that the animals are symbolic and not for eating.[10]

Plunder and re-installation

From the 16th to the 18th centuries, for 235 years, the painting decorated the refectory of the church of San Giorgio Maggiore, until 11 September 1797, when soldiers of Napoleon's French Revolutionary Army plundered the picture as war booty, during the Italian campaigns of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802). To readily transport the oversized painting — from a Venetian church to a Parisian museum — the French soldiers horizontally cut the canvas of The Wedding Feast at Cana, and rolled it like a carpet, to be re-assembled and re-stitched in France.

In 1798, along with other plundered works of art, the 235-year-old painting was stored in the first floor of the Louvre Museum; five years later, in 1803, that store of looted art had become the Musée Napoléon — the personal art collection of the future Emperor of the French.[14]

In the early 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars (1803–15), the repatriation and restitution of looted works of art was integral to the post–Napoleonic conciliation treaties. Appointed by Pope Pius VII, the Neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova negotiated the French repatriation of Italian works of art that Napoleon had plundered from the Papal States with the Treaty of Tolentino (1797) — yet, the prejudiced curator of the Musée Napoléon, Vivant Denon, falsely claimed that Veronese's canvas was too fragile to travel from Paris to Venice, and Canova excluded The Wedding Feast at Cana (1563) from repatriation to Italy, and, in its stead, sent to Venice the Feast at the House of Simon (1653), by Charles Le Brun.

In the late 19th century, during the Franco–Prussian War (1870–71), The Wedding Feast at Cana, then 308 years old, was stored in a box at Brest, in Brittany. In the 20th century, during the Second World War (1939–45), the 382-year-old painting was rolled up for storage, and continually transported to hiding places throughout the south of France, lest Veronese's art become part of the Nazi plunder stolen during the twelve-year existence (1933–45) of the Third Reich.[14]

In the early 21st century, on 11 September 2007 — the 210th anniversary of the Napoleonic looting in 1797 — a computer-generated, digital facsimile of The Wedding Feast at Cana was hung in the Palladian refectory of the Monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice. The full-sized (6.77m x 9.94m) digital facsimile is composed of 1,591 graphic files, and was made by Factum Arte, Madrid, on commission from the Giorgio Cini Foundation, Venice, and the Musée du Louvre, Paris.[15]

Restoration

.jpg.webp)

In 1989, the Louvre Museum began a painting restoration of The Wedding Feast at Cana (1563), which provoked an art-world controversy like that caused by the eleven-year Restoration of the Sistine Chapel frescoes (1989–99). Organised as the Association to Protect the Integrity of Artistic Heritage (APIAH), artists protested against the restoration of the 426-year-old painting, and publicly demanded to be included to the matter, which demand the Louvre Museum denied.[14]

To the APIAH, especially controversial was the Museum's removal of a rouge marron red hue over-painting of the tabard coat of the house steward, who is standing (left-of-centre) in the foreground supervising the black, servant-boy handing a glass of the new, red wine to the bridegroom. The removal of the red hue revealed the original, green colour of the tabard. In opposing that aspect of the painting's restoration, the APIAH said that Veronese, himself, had changed the tabard's colour to rouge marron instead of the green colour of the initial version of the painting.[15]

In June 1992, three years into the restoration of the painting, The Wedding Feast at Cana twice suffered accidental damages. In the first accident, the canvas was spattered with rainwater that leaked into the museum through an air vent. In the second accident, occurred two days later, the Louvre curators were raising the 1.5-ton-painting to a higher position upon the display-wall when a support-frame failed and collapsed. In falling to the museum floor, the metal framework that held and transported the painting punctured and tore the canvas; fortuitously, the five punctures and tears affected only the architectural and background areas of the painting, and not the faces of the wedding guests.[14]

Notes

- Louvre Visitor's Guide, English version (2004)

Sources

- Peter Murray; Linda, eds. (1997). Penguin Dictionary of Art and Artists (7th ed.). Penguin.

- Finocchio, Ross (2003). "Mannerism: Bronzino (1503–1572) and his Contemporaries". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2013-05-19.

- MacDonald, Deanna. "Paolo Veronese: The Wedding Feast at Cana — 1562–3". Great Works of Western Art.

- Hanson, Kate (Winter 2010). ""The Language of the Banquet: Reconsidering Paolo Veronese's Wedding at Cana". InVisible Culture: An Electronic Journal of Visual Culture (14, Aesthetes and Eaters – Food and the Arts): 5.

- Cicogna, Emmanuelle Antonio (1824). "Inscrizioni Nella Chiesa Di San Sebastiano e Suoi Contorni [Inscriptions in the church of St. Sebastion and its Environs]". Delle Inscrizioni Veneziane [Of the Venetian Inscriptions]. IV. Venice: Giuseppe Picotti. pp. 233–234.(in Italian).

- Wittkower, Rudolf (1999). "'High Baroque Classicism':Sacchi, Algardi, and Duquesnoy" (PDF). Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750, Vol II. pp. 86–87. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 Jan 2004..

- Reynolds, Joshua (1778). "A Discourse Delivered to the Students of the Royal Academy on the Distribution of the Prizes, December 10, 1771". Seven Discourses Delivered in the Royal Academy by the President. T. Cadell. pp. 124–125.

- "The Wedding Feast at Cana (1562–3), Paolo Veronese: Analysis". Art Encyclopedia.

- Lauritzen, Peter (1976). "The Architectural History of San Giorgio". Apollo. 104 (173): 4-11.

- Aline François. "Work: The Wedding Feast at Cana". Louvre Museum: Collection of Italian Paintings.

- Albala, Kenneth (2002). Eating Right in the Renaissance. University of California. p. 184..

- Priever, Andrea (2000). Paolo Caliari, called Veronese: 1528–1588. Köneann. p. 81.

- Lafarga, Manuel; Cháfer, Teresa; Navalón, Natividad; Alejano, Javier (2018) [2017]. Il Veronese and Giorgione in concerto : Diego Ortiz in Venice. Il Veronese y Giorgione en concierto : Diego Ortiz en Venecia (2nd ed.). Cullera (VLC): Lafarga & Sanz. ISBN 9788409070206. OCLC 1083839165.ResearchGate: 340814212

- Simons, Marlise (17 December 1992). "Repaired Masterpiece Redisplayed". The New York Times.

- Caliari, Paolo (January 2008). "Returning "Les noces de Cana"". Factum Arte. Archived from the original on 8 Jan 2020.

External links .

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Wedding at Cana (Veronese). |