Colorado Labor Wars

The Colorado labor wars were a series of labor strikes in 1903 and 1904 in the US state of Colorado, by gold and silver miners and mill workers represented by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). Opposing the WFM were associations of mine owners and businessmen at each location, supported by the Colorado state government. The strikes were notable and controversial for the accompanying violence, and the imposition of martial law by the Colorado National Guard in order to put down the strikes.

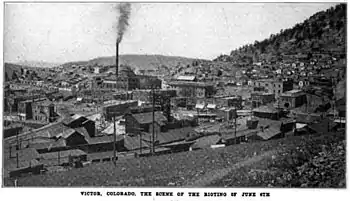

"Victor, Colorado, The Scene Of The Rioting Of June 6th", c. 1904. | |

| Date | 1903 - 1904 |

|---|---|

| Location | Colorado, United States |

A nearly simultaneous strike in Colorado's northern and southern coal fields was also met with a military response by the Colorado National Guard.[1]

Colorado's most significant battles between labor and capital occurred between miners and mine operators. In these battles the state government, with one exception, sided with the mine operators. Additional participants have included the National Guard, often informally called the militia; private contractors such as the Pinkertons, Baldwin–Felts, and Thiel detective agencies; and various labor entities, Mine Owners' Associations, and vigilante groups and business-dominated groups such as the Citizens' Alliance.

The WFM strikes considered part of the Colorado labor wars include:

- Colorado City, March to April 1903, and July 1903 to June 1904

- Cripple Creek mining district, March to April 1903, and August 1903 to June 1904

- Idaho Springs, May to September 1903

- Telluride, September to December 1903

- Denver, July to November 1903

- Durango, August to September 1903

Two scholars of American labor violence concluded, "There is no episode in American labor history in which violence was as systematically used by employers as in the Colorado labor war of 1903 and 1904."[2] The WFM as well embraced more violent strike tactics, and "entered into the one of the most insurgent and violent stages that American labor history had ever seen."[3]Page 93

Western Federation of Miners

In late 1902, the Western Federation of Miners boasted seventeen thousand members in one hundred locals.[4]p.58[5]p.15

Early victory in Cripple Creek

In January 1894, mine owners tried to lengthen the workday for Cripple Creek miners from eight to ten hours without raising pay. This action provoked a strike by the miners. In response, mine owners brought in strike breakers. The miners intimidated the strike breakers, so the mine owners raised a private army of an estimated 1,200 armed men. The gunmen were deputized by El Paso County Sheriff F. M. Bowers.[5]p.19 The miners were also armed, and were prepared for a confrontation.

Colorado Governor Davis Waite convinced the mine owners to go back to the shorter workday in what was called the "Waite agreement."[5]p.19 Governor Waite also called out the state militia to disarm the 1,200 gunmen who were no longer taking orders from the sheriff. The Waite agreement on miners' hours and wages subsequently went into effect, and lasted nearly a decade.[5]p.19-20

WFM builds power

Downtown Cripple Creek was destroyed by fires in 1896. Carpenters and other construction workers rushed to the area to rebuild the city, and unions arose to organize them. The carpenter's union and other unions owed their leverage to the Western Federation of Miners.[6]p.62 The strike victory in 1894 enabled the WFM to build labor organizations at the district, state, and regional levels.

Mining companies acted on a concern about miners stealing high grade ore by hiring Pinkerton guards. In one case three hundred miners walked out to protest the policy, the company negotiated, and the Pinkerton guards were replaced by guards nominated by the union. The new agreement stipulated that miners suspected of theft would be searched by a fellow miner in the presence of a watchman. To ensure a cooperative work force, mine managers and superintendents found it useful to urge all miners to join the union.[6]p.71-74

El Paso County included both heavily working class Cripple Creek and more conservative Colorado Springs, home to many of the mine owners. Backed by the pro-union Victor and Cripple Creek Daily Press, the unions elected union members to public office, and split the mining district from El Paso County, by creating Teller County.[6]p.69 Teller County was a union county where the eight-hour workday was enforced, and workers were paid union scale. Unions used social pressure, boycotts, and strikes to ensure that union goals were enforced. The unions were powerful enough to simply announce wages and hours, and any businesses that failed to comply were boycotted. Non-union products were eliminated from saloons and grocery stores.[6]p.70

WFM turns to socialism

Outside the Cripple Creek District, however, things were not going well for the WFM. The union had lost a strike in Leadville in 1896, and in 1899 there was another confrontation at Coeur d'Alene, Idaho which ended with hundreds of union miners locked up by the militia in temporary prisons. WFM Secretary-Treasurer Bill Haywood concluded that the companies and their supporters in government were conducting class warfare against the working class.[4]p.55

At their 1901 convention the WFM delegates proclaimed that a "complete revolution of social and economic conditions" was "the only salvation of the working classes."[6]p.179 WFM leaders openly called for the abolition of the wage system. By the spring of 1903 the WFM was the most militant labor organization in the country.[5]p.15 This was a considerable change from the WFM's founding Preamble, which envisioned a future of arbitration and conciliation with employers, and an eventual end to the need for strikes.[3]p.23

Craft versus industrial unionism

Bill Haywood, the WFM's powerful secretary treasurer and second in command, had adopted the industrial unionism philosophy of his mentor, former WFM leader Ed Boyce. Boyce disagreed with Samuel Gompers, head of the AFL, over union organization.[5]p.23 Haywood thought that unions should cover whole industries, and that the WFM should extend to workers at ore processing mills as well, and that all workers in an industrial union should stand up for the rights of other workers. Haywood believed he had the necessary weapon to force the mill owners to negotiate: the solidarity of the workers in the mines that fed the mills.[4]p.60,79

Under the leadership of Ed Boyce, Cripple Creek unions also helped to organize, and provided leadership for the Western Labor Union, a federation formed in response to the American Federation of Labor (AFL) which had federated the craft unions in the east. In 1899, the WFM wrote industrial unionism, its response to the AFL's craft philosophy, into its charter.[6]p.63,68

Anti-union forces in Colorado

Colorado's employers observed the WFM's socialist pronouncements with trepidation, because the union's goal was now the elimination of private ownership of the mines.[5]p.28

Republican James Peabody ran a campaign for governor of Colorado pledging to restore a conservative government which would be responsive to business and industry. He nonetheless expressed warm sentiments toward unionism while campaigning in the Cripple Creek District. Labor organizations were not persuaded and opposed his candidacy, but the Republicans gained control of the state government[5]p.39-41 when the Democrats and Populists split the progressive ticket.[6]p.201

Peabody saw the Western Federation of Miners as a threat to his own class interests, to private property, to democratic institutions, and to the nation itself. He promised in his inaugural address to make Colorado safe for investments, if necessary using all the power of the state to accomplish his aims.[5]p.45

National employers' movement

A national employers' movement aimed directly at the power of unions was gaining strength. In his 1972 book Colorado's War On Militant Unionism, George Suggs, Jr. reported that antiunion employers' organizations in Ohio, Illinois, Missouri, and Wisconsin had effectively stopped the growth of unions through open shop campaigns.[5]p.65-66

In 1903, David M. Parry delivered a speech at the annual convention of the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) that was a diatribe against organized labor. He argued that unions' goals would result in "despotism, tyranny, and slavery." Parry advocated the establishment of a great national anti-union federation under the control of the NAM, and the NAM responded by initiating such an effort.

Colorado employers' movement

Among those present at the Chicago conference was President James C. Craig of the Citizens' Alliance of Denver.[5]p.68 Within three weeks after its creation on April 9, the Citizens' Alliance of Denver had enrolled nearly 3,000 individual and corporate members, and had a war chest of nearly $20,000. The Citizens' Alliance of Denver believed in the principle of an employer's absolute control over the management of business. Craig led the fight against union labor throughout Colorado.[5]p.68 The organization had a "clandestine character," and all the inner workings of the organization were enshrouded "in deep secrecy," raising the possibility that "the group might take extralegal action against all organized labor."[5]p.69[7] The alliance stepped into the middle of labor disputes, and one of their early accomplishments was preventing amicable settlements between companies and their unions.[5]p.70 Other employers' alliances in Colorado followed the constitutional formula of the Citizens' Alliance of Denver.[5]p.69

Pinkerton detectives

James McParland, famous for his role in prosecuting the Molly Maguires years earlier in Pennsylvania, ran the Denver Pinkerton office. He directed the activities of scores of spies that had been placed within the Western Federation of Miners.[4]p.89 Charles MacNeill, general manager of the USRRC refining company, had been a Pinkerton client since 1892.[4]p.327

Eight-hour day issue

The agreement settling the 1894 strike in the Cripple Creek District provided an eight-hour day for miners.[8]p.219 The WFM argued that working long hours in a mine or smelter were hazardous to workers' health, and that the eight hour day should become state law for mine and mill workers. Republicans opposed the law, and sought an opinion from the Colorado Supreme Court. The Court advised that such a law would be unconstitutional.[8]p.219

Then a similar law was passed in Utah, and it withstood a U.S. Supreme Court challenge. Legislators used the precise language from the Utah law in the legislation. The Colorado Supreme Court again ruled that the law was unconstitutional, this time with respect to the state constitution. It would take an amendment to the Colorado Constitution to satisfy the Colorado high court.[8]p.219

The amendment to the Colorado Constitution was endorsed by the Republican, Democratic, and Populist parties. The Colorado State Legislature put the matter to a referendum, which submitted to voters.[8]p.219 On November 4, 1902, Colorado voters passed the amendment 72,980 to 26,266, an approval rate of greater than 72 percent.[8]p.218-219

The new law, with the force of a state constitutional amendment, had only to go back to the state legislature in the 1903 session for final implementation. Under pressure from mining companies,[8]p.219-220 the Colorado state government ignored the results of the referendum, and did not pass the enabling legislation.[4]p.65 Governor Peabody, elected with pro-business support, had the opportunity to rescue the amendment, but opted not to do so. In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt would write that Peabody's failure to pass an 8-hour law was "a grave error" and "unpardonable."[8]p.218-219

Strike in Idaho Springs, May to August 1903

In Idaho Springs, WFM miners struck in May 1903 for an eight-hour day.

In July, a dynamite attack in the middle of the night destroyed the powerhouse at the Sun and Moon mine, where strikebreakers were working. The attackers fled, leaving behind a union miner mortally injured by a premature dynamite explosion. A number of union officials were arrested that same night, and accused of complicity in the bombing.[5]p.76

On the night after the dynamite attack, The following night, nearly 500 people, including most businessmen and city officials, met to decide on a response. After angry speeches, the crowd marched to the jail, removed the prisoners and expelled 23 union members from the town. Suggs wrote that the Citizen's Protective League,

"directed law enforcement, held secret strategy sessions, ordered the arrest and interrogation of suspects whom they held incommunicado, watched incoming trains, and warned union sympathizers to leave town."[5]p.77

Although this was a "brazen, illegal exercise of power,"[5]p.77 Governor Peabody ignored it.[5]p.79 District Judge Frank W. Owers ruled the expulsions illegal, and issued an injunction against the League to prevent interference with the return of the union miners. Eight WFM members returned to Idaho Springs, were arrested and tried for the powerhouse explosion, and were acquitted. Owers then issued bench warrants for 129 of the Citizens' Protective League vigilantes, charging them with "rioting and making threats and assaults." The district attorney had cooperated with the League, and refused to prosecute the warrants.[5]p.79

Durango smelter strike, August and September 1903

The Western Federation of Miners local at Durango, Colorado, ordered a strike on 29 August 1903. Out of the 200 employees of the Durango smelter, 175 walked off, demanding an 8-hour day. The strike effectively stopped work at the smelter for several days, but the smelter replaced the strikers, and resumed normal operation. Extra deputies were hired, and arrangements made to house workers on the smelter grounds. The strike failed.[9]

First Colorado City mill workers strike, March and April 1903

In August 1902, the WFM organized the mill workers of Colorado City, who refined the ore brought down from the Cripple Creek District. The mill operators hired Pinkerton detective A.H. Crane to infiltrate and spy upon the local union. Crane became "rather influential" in the union, and forty-two union men were fired. It was "practically admitted" that the dismissals were simply for joining the union.[10]p.73 Charles MacNeill, vice-president and general manager of the United States Reduction and Refining Company (USRRC), refused to negotiate with the union,[6]p.200 declining even to accept a document with the union's list of demands. The demands were the rehiring of the union workers, the right to organize, and a wage increase.[5]p.47 Thwarted in their efforts to negotiate, the mill workers went on strike on February 14 to protest the dismissals. When other mills also declined to accept the union's terms, they were struck as well.

There was close cooperation between the mill operators and El Paso County law enforcement. General Manager MacNeill received an appointment as deputy sheriff, and for a time the USRRC paid the salaries of additional deputies protecting its properties. Limited production continued with non-union workers,[5]p.47 and strike-breakers were hired with the understanding that their jobs were permanent. Tensions mounted on the picket line, and the sheriff appointed more than seventy men for strike duty. But MacNeill was demanding 250 guards for the USRRC properties alone.

W.R. Gilbert, sheriff of El Paso County, requested troops from the governor, writing: "It has been brought to my attention that men have been severely beaten, and there is grave danger of destruction of property. I accordingly notify you of the existence of a mob, and armed bodies of men are patrolling the territory, from which there is a danger of commission of felony."[10]p.91

Historian Benjamin Rastall declared that there was "No apparent necessity for the presence of troops... Colorado City was quiet... No destruction of property had occurred, and 65 deputies would seem an ample number."[10]p.76 Gilbert later testified that the troops were necessary not to suppress existing violence, but to prevent it. The investigation revealed enormous pressure on the sheriff from the refining companies[5]p.48 to secure state troops.

Governor sends in troops

More than three hundred National Guard soldiers arrived in Colorado City to protect the mills, and escort non-union employees to and from work.[5]p.50 The Colorado City mayor, the chief of police, and the city attorney complained to the governor in a letter that "there is no disturbance here of any kind." At least 600 citizens of Colorado City opposed the deployment by signing petitions or sending wires to the governor stating, for example, that "a few occasional brawls" did not justify military occupation. But the soldiers dispersed union pickets. They searched union member's homes and they put the union hall under surveillance.[10]p.77

Governor Peabody worked in close association with Craig to form an employer-based citizens' alliance for his home town of Canon City, which the governor later joined.[5]p.80 He appointed an anti-union mine manager and former sheriff's deputy[6]p.80 from the Cripple Creek District, Sherman Bell, to the office of adjutant general,[5]p.80

For secretary of Colorado's state military board, Peabody appointed John Q. MacDonald, manager of the Union smelter at Florence, part of the USRRC, the company in the middle of a Western Federation of Miners strike. Peabody appointed two aides-de-camp, Spencer Penrose and Charles M. MacNeill, who were, respectively, treasurer and vice-president/general manager of the USRRC.[5]p.82-83 Peabody described MacNeill and Penrose as his two "Colorado Springs Colonels."[6]p.200

First Cripple Creek strike, March 1903

The WFM asked all mines not to sell ore to the ore mills in Colorado City, with the understanding that the union would call a strike at any mine not cooperating. The mine owners met on 5 March 1903, and refused to stop selling ore to the struck mills. The businessmen of Victor convinced the WFM to delay the strike one week, to see if the mill strike could be negotiated without the strike spreading to the mines.[10]

On 14 March, the union locals at Cripple Creek declared a strike against 12 mines shipping ore to the Colorado Reduction and Refining mills, and 750 miners walked out. By this time, the Portland and Telluride mills had signed agreements with the union. Two mines, the Vindicator and Mary McKinney agreed not to sell ore to the struck mills, and were not struck. Some mines had contracts with the struck mills, and could not stop shipping ore without incurring legal penalties.

The governor spoke to representatives of the union, but he simultaneously sought information about obtaining "an allotment of Krag guns," because "a serious strike was imminent."[6]p.203

Governor Peabody brokers an agreement

Governor Peabody invited both sides to meet in the governor's office on 14 March. Manager MacNeill walked out of the negotiations, but the Portland mill and Telluride mill signed agreements to hire back fired union members, and not to discriminate against union members going forward. The strikes against those two mills were called off, but those against the two Colorado Reduction and Refining mills continued. The governor agreed to withdraw the National Guard troops.[10]

Manager MacNeill finally succumbed to the governor's arm-twisting, and verbally promised not to discriminate against union workers in the future.[10] The strikes in both Colorado City and Cripple Creek were called off.

On 1 May, after the strike had ended, the WFM negotiated a wage increase for the mill workers at the Portland and Telluride mills. Wages of $1.80 per day for the lowest-paid workers increased to $2.25. Again, the mills of the Colorado Reduction and Refining Company held out, and refused to increase wages.[10]

Denver mill workers' strike, July 1903

Western Federation of Miners union members working at the Grant and Globe smelters in Denver proposed a reduction in the work day from the existing 10 or 12 hours down to 8. American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO), which owned the smelters, refused. On 3 July 1903, at a meeting of the local also attended by national officers Charles Moyer and Bill Haywood, the mill workers voted to strike. The strikers immediately went to the Grant smelter and ordered the employees to quit working. They then went to the Globe smelter and did likewise; 5 or 6 workers at the Globe smelter were beaten and kicked by the strikers. By the time the company manager learned of the strike, the smelters were closed and the fires extinguished. The strikers forced three of the furnaces to shut down so quickly that molten metal congealed in the pipes, requiring laborious repair work.[11]p.132-137

The number of workers idled at the two smelters was 773, about half of whom were union members. The union established pickets at the two smelters, in spite of a court injunction against picketing. On 7 July, the Globe smelter brought back 20 employees to do repair work caused when the furnaces were extinguished unexpectedly, while a police force of 31 guarded both plants. The picketing remained peaceful, and the police guards were withdrawn on 21 July. [11]p.137-143

WFM members at ASARCO's Eiler smelter in Pueblo made the same demand for 8-hour days, but agreed to keep working when management agreed to grant to its Pueblo employees any concessions won by the WFM strikers in Denver. Likewise the owners of the Argo smelter in Denver agreed to match any concessions by the Grant or Globe smelters [11]p.144-146

On 19 July, Asarco brought 62 workers from Missouri to Denver, but when they learned of the strike, all but 20 left town. The Grant smelter had out-of-date equipment, and the company decided to keep it closed. But in mid-August, ASARCO restarted its Globe smelter. Striking employees were re-hired only if they declared that they had quit the union.[11]p.143-144

On Thanksgiving Day 1903, a crowd of strikers attacked 7 workers at the Globe smelter, also badly beating a policeman who came to their aid. Nine of the assailants were tried and sentenced to 6 months in jail. The strike was never officially called off.[11]p.145

One Pinkerton spy was assigned to sabotage the union's relief program during a strike. According to Bill Haywood, Secretary-Treasurer of the WFM, the man at first overpaid strike benefits, and then distributed insufficient food for the miners' families.[12]

Second Colorado City mill workers' strike, July 1903

MacNeill hired back most of the strikers, but they were offered different, less satisfactory jobs than they'd held before. MacNeill had promised to rehire all but fourteen union members, yet forty-two WFM members were not rehired. Some union men refused the proffered jobs because they had once belonged to other union men who were not re-hired. The union felt that MacNeill had acted in bad faith. On 3 July 1903, the WFM struck the two ore processing mills of the Colorado Reduction and Refining Co. Only nine men walked out.

Although the Telluride mill had increase wages on 1 May, on 5 July the company announced that it was cutting back part of the increase. Under the new schedule, the lowest-paid position, which had recently increased from $1.80 to $2.25 per day, would be cut back to $2.00 per day.

On 25 August 1903, Walter Keene, the head precipitator at the Telluride mill was attacked by a crowd of union members inside the mill, hit on the head with a dinner pail, and his life threatened if he did not either join the union or quit his job. Keene promptly resigned. H. W. Fullerton, the manager of the Telluride mill fired two of Keene's assailants, and told the union that violence against non-union employees would not be tolerated. He reminded them that he had agreed in writing not to discriminate against union men, and expected the union likewise not to harass non-union employees. The union demanded that Fullerton rehire the two men he had fired, and when he refused, the WFM struck the Telluride mill.[10]p.76

Second Cripple Creek miners' strike, August 1903

The WFM again tried to shut down the mines supplying ore to the struck mills in Colorado City. But this time, the leadership decided on a massive show of union force. Rather than strike just the mines supplying ore to the struck mills, as before, on 8 August, the WFM shut down the entire mining district, declaring strikes at about 50 mines, and idling 3,500 workers.[6]p.205 Although the union had no issue with mine owners, the WFM hoped that a larger strike would put more pressure on mill owners to settle.[10]p.76 The Cripple Creek district had been a union stronghold for the Western Federation of Miners since its success in the strike of 1894, and it seemed a safe base from which to expand union power into the ore processing mills.

The strike had been called by the district council of the WFM, representing the leaders of the various WFM union locals around the mining district. A recent change in the WFM constitution gave union leadership the right to call strikes in support of other locals without a strike vote, and the rank and file were not given the opportunity to vote on the strike. A large majority of the union miners were said to be opposed to the strike; Rastall estimated up to 90 percent were against.[10]p.89

The WFM hoped to win the strike by having the mine owners pressure mill operators to settle.[5]p.86 However, although some mine owners wanted the mills to accept WFM demands, the Cripple Creek Mine Owners' Association preempted defections, declaring that the dispute with the mills should not have caused a strike of mines in the Cripple Creek District.[6]p.206 That argument by the CCMOA resonated with many of the union miners, who had given up their right to vote on strikes individually in their convention,[5]p.85 and may have privately had second thoughts.

But the maverick owner of the Portland mine, who had come to terms with the union five months earlier over the mill workers' strike, once again broke ranks with the other mine/mill operators and came to an agreement with the WFM. Five hundred miners returned to work,[5]p.85 giving hope to the WFM leadership.

The WFM wielded tremendous economic leverage in the Cripple Creek District.[5]p.86 But merchants were concerned that the union seemed willing to hold the local economy hostage for the sake of mill workers outside the district. The concept of industrial unionism may have been obvious to union miners, but it wasn't a persuasive philosophy to their creditors. Many of the merchants announced that they would sell only for cash, cutting off credit for miners on strike. Then Craig arrived to help the merchants establish the Cripple Creek District Citizens' Alliance, with about five hundred businessmen and others joining up in the first week.[5]p.88

By the end of August 1903 the entire district was polarized and tense, with any chance for a settlement rapidly slipping away. Mine owners and businessmen had concluded that the central issue of the strike was who would control the district,[5]p.89 and they were reluctant to give up any of the control that they had.

Several incidents occurred in the Cripple Creek District, some strike related. A union member's house burned, and so did the shaft-house at the Sunset-Eclipse mine. Some individuals were beaten. Sheriff Henry Robertson, a member of the WFM, deputized guards for the mines, their salaries provided by the mine operators. The sheriff saw no reason to request state support, insisting that he was investigating the crimes. The county commissioners[5]p.89 and the mayor of Cripple Creek supported the sheriff. The mine owners disagreed, and so did Mayor French of nearby Victor, who was manager of the C.C.C. Sampler.[10]p.94

Notable labor organizer, Mary "Mother" Jones, was ordered to be kept out of the state by the governor. She managed to enter in order to aid the strike, and she wrote a letter to Governor Peabody saying, "I wish to notify you, governor, that you don't own the state. When it was admitted to the sisterhood of the states, my fathers gave me a share of stock in it; and that is all they gave you. The civil courts are open. If I break a law of state or nation it is the duty of the civil courts to deal with me. That is why my forefathers established those courts to keep dictators and tyrants such as you from interfering with civilians."[13]

National Guard sent to Cripple Creek

Although business interests had supported National Guard intervention in Colorado City,[5]p.50 Governor Peabody hesitated to send the guard to Cripple Creek. WFM President Charles Moyer had portrayed the Colorado City intervention as unnecessary,[5]p.90 and certainly many had seen it that way.[5]p.50 Peabody appointed three individuals to an investigative team, two of whom had already recommended intervention.[5]p.91 The union was not consulted during their investigation, and, among those consulted, only Sheriff Robertson and Mayor Shockey spoke out against intervention. The commission concluded that a "reign of terror" existed in the district, and intervention was justified. The Cripple Creek Mine Owners' Association agreed to secretly finance the troops.[5]p.92-93 By the end of September 1903 nearly a thousand soldiers were guarding the Cripple Creek District mines and patrolling the roads.

As in Colorado City, the civil authorities and a large number of citizens in the Cripple Creek District deplored the intervention. The county commissioners unanimously condemned it. The Victor city council claimed that Mayor French had deliberately misrepresented conditions and the wishes of his constituents when he supported intervention. Sheriff Robertson declared that the governor had exceeded his authority. Mass meetings and demonstrations opposed the decision.[5]p.94 More than two thousand signatures were collected on petitions protesting the action.[6]p.207

The CCMOA, the Cripple Creek Citizens' Alliance, and other employers' associations supported the action.[5]p.94 The goal of the employers' organizations was not just ending the strike, but terminating the influence of the union. The CCMOA announced plans to sweep the WFM from the district.[6]p.27 Peabody facilitated that goal in his orders to Sherman Bell, which directed the National Guard to assume the responsibilities of the local sheriff and civil officials.

Military rule

In her 1998 book All That Glitters, historian Elizabeth Jameson quoted a Pinkerton detective reporting that there was "no radical talk or threats of any kind that I can hear, on the part of the miners."[6]p.207-208 But the National Guard leaders were ready for war. A thousand Krag-Jorgensen rifles and sixty thousand rounds of ammunition were sent to the district.[6]p.210 Sherman Bell, the former mine manager and leader of the Guard forces declared: "I came to do up this damned anarchistic federation." Another Guard officer, Thomas McClellend, said: "To hell with the constitution, we aren't going by the constitution." Bell justified his actions as a "military necessity, which recognizes no laws, either civil or social."[6]p.207 Sherman Bell supplemented his state salary with $3,200 annual pay from the mine owners.[4]p.62 Rastall wrote that Bell returned a hero from the Spanish–American War, but lost popularity because of his "overbearing ways and self-conceit."[10]p.157

George Suggs observed,

Using force and intimidation to shut off debate about the advisability of the state's intervention, Brigadier General John Chase, Bell's field commander, systematically imprisoned without formal charges union officials and others who openly questioned the need for troops. Included among those jailed were a justice of the peace, the Chairman of the Board of County Commissioners, and a member of the WFM who had criticized the guard and advised the strikers not to return to the mines.[5]p.95

So frequently were individuals placed in the military stockade or "bull pen" at Goldfield for reasons of "military necessity" and for "talking too much" in support of the strike that the Cripple Creek Times of September 15 advised its readers not to comment on the strike situation. Not even the newspapers escaped harassment. When the Victor Daily Record, a strong voice of the WFM, erroneously charged that one of the soldiers was an ex-convict, its staff was imprisoned before a retraction could be published.[5]p.96

While Victor Daily Record editor George Kyner and four printers were in the bullpen, Emma Langdon, a Linotype typesetting machine operator married to one of the imprisoned printers, sneaked into the Daily Record office and barricaded herself inside. She printed the next edition of the paper, and then delivered it to the prisoners in the bullpen,[6]p.209 surprising the guards in the process.

On September 10 the National Guard began "a series of almost daily arrests" of union officers and men known to be strongly in sympathy with the unions.[10]p.80 When District Judge W. P. Seeds of Teller County held a hearing on writs of habeas corpus for four union men held in the stockade, Sherman Bell responded: "Habeas corpus be damned, we'll give 'em post mortems."[4]p.62 Approximately ninety cavalrymen entered Cripple Creek and surrounded the courthouse. The prisoners were escorted into the courtroom by a company of infantry equipped with loaded rifles and fixed bayonets,[10]p.101 and the soldiers remained standing in a line during the court sessions. Other soldiers took up sniper positions and set up a gatling gun in front of the courthouse. Angered by the intimidating display, an attorney for the prisoners refused to proceed and left the court.[5]p.97 Undaunted by the military presence, the judge ruled for the prisoners. Judge Seeds commente:

I trust that there will never again be such an unseemly and unnecessary intrusion of armed soldiers in the halls and about the entrances of American Courts of Justice. They are intrusions that can only tend to bring this court into contempt, and make doubtful the boasts of that liberty that is the keynote of American Government.[14]

Yet Chase refused to release the men until Governor Peabody ordered him to do so.

Even those Colorado newspapers which had supported the intervention expressed concern that court orders were not being obeyed by the National Guard.[5]p.98 The Army and Navy Journal editorialized that using the Colorado National Guard in such a biased way "was a rank perversion of the whole theory and purpose of the National Guard."[10]p.99

The Colorado Constitution of the period "declares that the military shall always be in strict subordination to the civil power."[10]p.101 The district court ruled that Bell and Chase should be arrested for violating the law. Bell responded by declaring that no civil officer would be allowed to serve civil processes to any National Guard officer on duty.

Within a week after the arrival of troops, the Findley, Strong, Elkton, Tornado, Thompson, Ajax, Shurtloff, and Golden Cycle mines began operations again, and recruited replacement workers brought in from outside the district. The mine owners recruited from surrounding states, not telling potential miners that there was a strike. When they arrived and learned of the strike, some were "practically forced" to go to work. Emil Peterson, a worker recruited from Duluth, ran when he realized the purpose of the military escort. Lieutenant Hartung fired a pistol at him as he ran. A warrant for the lieutenant was ignored by the military officers.[10]p.102

The CCMOA began to pressure companies to fire union miners who were still working in mines that had not been struck. Companies that refused to do so, or who in some other way refused to join the employers' alliance movement, were blacklisted.[5]p.107-115 When the Woods Investment Company ordered their employees to quit the WFM, the employees joined the strike instead. The superintendent and the shift bosses accompanied all of the workers out the door.[6]p.209

Plot to derail a train

A railroad track walker had discovered missing spikes.[6]p.210

The incident at first appeared to be an attempt to wreck a train carrying strike breakers to non-union mines.[4]p.69 A former member of the WFM by the name of H.H. McKinney was arrested and confessed to K.C. Sterling, a detective employed by the Mine Owners' Association, and D.C. Scott, a detective for the railroad, that he had pulled the spikes. McKinney implicated the president of District Union No. 1, the president of the Altman local, and a WFM activist in an alleged conspiracy to wreck the train. But then McKinney repudiated his confession by writing a second confession, stating that he had been promised a pardon, immunity, a thousand dollars, and a ticket to wherever he and his wife wanted to go, to "any part of the world," if he would lie about the spikes. He didn't know who had pulled them, and the first confession had been brought to him, already prepared, while he was in the jail.[6]p.210

McKinney and his wife were then given new suits of clothing, and he was granted unusual privileges, allowed to spend time away from the jail for free meals and to see his wife. A trial was held for the three union men, and McKinney changed his story again, this time asserting that his original confession was true, and that the repudiation was false. He testified that he didn't know who paid for the meals and clothes.[10]p.105-106

But some of the testimony in the trial implicated the detectives who had arrested McKinney, and suggested that the detectives pulled the spikes, intending to blame the union. One of the two arresting detectives admitted to being employed by the CCMOA for secret work, and a third detective confessed to helping plot the derailing. One of the detectives had also been seen with another man working on the railroad tracks.[6]p.211[4]p.70

McKinney testified he would be willing to kill two hundred or more people for five hundred dollars.[10]p.107 In his autobiography, Bill Haywood, the secretary treasurer of the Western Federation of Miners, stated that the president of the Victor Miners' Union and many other union men were on the train.[15] Haywood charged that McKinney had also worked with a third detective named (Charles) Beckman, from the Thiel Detective Service Company. Beckman had worked undercover as a member of Victor Miners Union No. 32 since April. His wife was an undercover member of the union's Ladies' Auxiliary.[6]p.211

Additional testimony indicated that Detective Scott inquired of a railroad engineer named Rush, where would be the worst place for a train wreck. Rush pointed out the high bridge where, if a rail was pulled, the train would crash three or four hundred feet down an embankment, killing or injuring all on the train. Scott told Rush to be on the lookout for damaged track that night at that spot. Later that evening Rush stopped his train, walked ahead on the track and discovered that spikes had been pulled.[16]:142–143

Sterling admitted in his testimony that the three detectives had tried to induce WFM members to derail the train.[6]p.211 But in Bill Haywood's perception, Detectives Sterling and Scott put all the blame on McKinney and Detective Beckman.[16]:142–143 A jury of non-union ranchers and timbermen unanimously found the three union men "not guilty."[4]p.70 McKinney was allowed to go free on the train-wrecking charge, but was later arrested for perjury. He was released on $300 bond, which the Mine Owners' Association covered.[6]p.211 Detectives Sterling, Scott, and Beckman were never arrested.

Telluride strike, September 1903

WFM members walked out of the ore processing mills at Telluride on 1 September 1903, for a reduction in the workday from 12 hours to 8. The mill shutdowns caused a shutdown of most of the mines which had no place to send their ore to be processed. The ore mill for the Tom Boy mine tried to reopen with a nonunion workforce, but the WFM struck the mine, and posted picketers armed with pistols and rifles around the Tom Boy’s mine yard, preventing strikebreakers from entering.[11]

In November, mine owners at Telluride made several requests that the governor send in national guard troops. There were no disturbances, but the owners wanted to reopen the mines with strikebreakers, and wanted national guard protection. The governor sent a committee of five led by the attorney general. The committee reported that Telluride was peaceful, but that the union picketers were armed, and if the mines reopened, local authorities would not be able to prevent violence. Governor Peabody asked President Theodore Roosevelt to send in US Army soldiers; the president refused. The governor sent in 500 Colorado National Guard troops, who arrived in Telluride on 24 November 1903.[11]

On 21 November, deputy sheriffs confronted the armed picketers at the Tom Boy mine, and demanded that they surrender their weapons. The picketers refused, and the deputies arrested five of them. Six more picketers were arrested on 24 November, and when the president of the WFM local visited the men in jail, he was arrested as well; all were charged with conspiracy to commit a misdemeanor.[11]

Deputy sheriffs began arresting striking miners and charging them with vagrancy. Anyone without a job, meaning all those on strike, were being found guilty of vagrancy, so that WFM strikers had to leave the district to avoid repeated arrests and fines. On 23 December, 11 WFM members were arrested and charged with intimidating strikebreakers. The charges were dropped 5 days later, and the 11 were released, but they were released from the jail in Montrose, Colorado, 71 miles away from Telluride.[11]

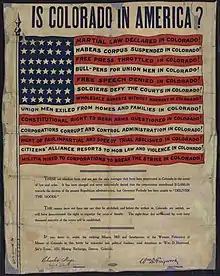

Telluride inspires a famous poster

During the Telluride strike, a union man named Henry Maki had been chained to a telegraph pole. Bill Haywood used a photo of Maki to illustrate a poster displaying an American flag, with the caption, "Is Colorado in America?"[16]:141 The poster was widely distributed, and gained considerable attention for the WFM strike. Peter Carlson describes the "desecrated flag" poster as famous, and "perhaps the most controversial broadside in American history."[4]p.71

The WFM obtained an injunction against further deportations in Telluride, and WFM President Charles Moyer decided to go there to test the injunction. Moyer was arrested on a charge of desecrating the flag for having signed the poster, and the National Guard refused to release him when the civilian courts ordered them to do so. For the journey, Moyer had accepted an offer from a Cripple Creek striker by the name of Harry Orchard to travel along as a bodyguard. Orchard later became one of America's most famous, and controversial, assassins.[4]p.71

National guard troops left Telluride on 1 January 1904. By then, the mines and mills were operating with imported, nonunion labor.[11]

After the militia left, dozens of expelled strikers returned to the area. The Citizens' Alliance responded by issuing National Guard rifles to attendees at their meeting. The meeting was adjourned and the armed vigilantes immediately rounded up seventy-eight of the union men and sympathizers, expelling them again.[4]p.70 A Telluride merchant, Harry Floaten, had been deported for his union sympathies. He, along with others, tried for three days to meet with Governor Peabody about their treatment at the hands of an anti-union mob, but Peabody refused to see them.[5]p.139 Floaten penned a bitter parody that, according to Peter Carlson, "channeled the miners' frustrations.”:

- Colorado, it is of thee,

- Dark land of tyranny,

- Of thee I sing;

- Land wherein labor's bled,

- Land from which law has fled,

- Bow down thy mournful head,

- Capital is king.[4]p.77

Strikes not called

Once the Western Federation of Miners shut down the Cripple Creek mining district, the national leadership tried to bring as many locals out on strike as possible, to shut down metal mining in the state. But the locals were autonomous, and some refused to strike.

The Silverton WFM local was asked by the national leadership to strike the mines there in support of the Durango mill strike, which started on 29 August 1903. Most of the ore processed by the Durango mills came from Silverton. But the Silverton local had a contract with the mines that would not expire until 1905, and the Silverton miners were unwilling to abrogate their agreement.[17]

On 19 August 1903, the local WFM union at Ouray voted 150 to 50 not to strike.[18]

Other WFM locals which declined to strike were union smelter workers at Leadville and Pueblo.[19]

Colorado National Guard ensures its status

In the analysis of historian Melvyn Dubofsky, the Colorado National Guard served private capital more than the public interest.[20] Yet the National Guard leadership wasn't beyond reminding their wealthy benefactors to live up to their arrangement, even if it required a little mayhem, or even gunfire.

An item in The Public, a Chicago magazine, printed a sworn affidavit from a member of the Colorado militia, Major Francis J. Ellison:

When General Bell first sent me to Victor I offered him certain evidence in regard to the perpetrators of the Vindicator explosion, which he has failed to follow up, but which would have led to the arrest and conviction of the men who are responsible for the placing of that infernal machine. At about the 20th of January, 1904, by order of the adjutant of Teller County military district, and under special direction of Major T. E. McClelland and General F. M. Reardon, who was the Governor's confidential adviser regarding the conditions in that district, a series of street fights were commenced between men of Victor and soldiers of the National Guard on duty there. Each fight was planned by General Reardon or Major McClelland and carried out under their actual direction. Major McClelland's instructions were literally to knock them down, knock their teeth down their throats, bend in their faces, kick in their ribs and do everything except kill them. These fights continued more or less frequently up to the 22d of March. About the middle of February General Reardon called me into Major McClelland's office and asked me if I had a man in whom I could place absolute confidence. I called in Sergeant J. A. Chase, Troop C, First Cavalry, N. G. C., and, in the presence of Sergeant Chase, he stated to me that, owing to the refusal of the Mine Owners' Association to furnish the necessary money to meet the payroll of the troops, it had become necessary to take some steps to force them to put up the cash, and he desired me to take Sergeant Chase and hold up or shoot the men coming off shift at the Vindicator mine at 2 o'clock in the morning. I told General Reardon that I was under the impression that most of these men caught the electric car that stopped at the shaft house so that such a plan would be impracticable. He then said to me that the same end could be reached if I would take the sergeant and fire fifty or sixty shots into the Vindicator shaft house at some time during the night. Owing to circumstances making it impossible for Sergeant Chase to accompany me, I took Sergeant Gordon Walter of the same troop and organization, and that same night did at about 12:30 o'clock fire repeatedly into the Vindicator and Lillie shaft house. Something like sixty shots were fired from our revolvers at this time. Afterwards we mounted our horses and rode into Victor and into the Military Club, reporting in person to General Reardon and Major McClelland. The next day General Reardon directed me to take Sergeant Walter and look over the ground in the rear of the Findlay [sic] mine with a view of repeating the performance there, but before the plan could be carried out General Reardon countermanded the order, stating his reason to be that the mine owners had promised to put up the necessary money the next day, which, as a matter of fact, they did. General Reardon, in giving me directions regarding the shooting up of the Vindicator shaft house, stated that Governor Peabody, General Bell, he himself, and I were the only ones who knew anything about the plan.[21]

The magazine stated that Ellison's affidavit was corroborated by the affidavits of Chase and Walters.[21] The Durango Democrat reported that Major Ellison's testimony was "unquestionably true, being corroborated by the affidavits of other guardsmen, and victims of the whitecappers."[22]

Union violence, anti-union violence, and unnatural disasters

Using dynamite to effect social changes seems to have been a tradition in the Cripple Creek District even when there was no strike. Private assay offices catered to the individual prospector, and to miners who stole gold out of the mines. Mine owners were concerned about ore theft, and several large mines hired Pinkerton agents beginning in 1897,[6]p.75 but high grading — the theft of rich gold ore by miners — was difficult to control. Jameson observes that "the Mine Owners' Association paid (someone) to blow up assay offices in 1902 to try to stop high grading."[23]

Explosion in the Vindicator mine

On 21 November 1903, two management employees at the Vindicator mine were killed by an explosion at the 600 foot level. The coroner's jury could not determine what had caused the explosion.[6]p.211-212 Although the mine was heavily guarded by soldiers and no unauthorized personnel were permitted to approach, the CCMOA blamed the explosion on the WFM. Fifteen strike leaders were arrested but were never prosecuted.

WFM member Harry Orchard later confessed to setting the dynamite bomb on the 600-foot level next to the mine shaft, and rigging it to explode when the next person got off on that level. He wrote that he and another WFM member, Billy Aiken, had entered the mine through an old unused shaft, and that a third, Billy Gaffney, had stayed at the surface as a lookout. Orchard wrote that he had been paid to plant the dynamite by Mr. Davis, the president of the Altman local, one of the WFM locals in the Cripple Creek district. When they heard nothing about an explosion during the next few days, they assumed that their bomb had failed to explode. But they had mistakenly set the bomb on an inactive level, and it did not go off until some time later, when the superintendent and the shift boss got off to inspect the 600-foot level, and set off the dynamite.[24]

The union blamed the employers for the Vindicator mine explosion, claiming it was just another devious plot that went wrong. They issued a pamphlet which attributed the motive for the explosion to the fact that "it was currently reported that the State militia was about to be ordered home, and the mine owners' association was against this removal."[25] The Vindicator explosion occurred not quite three months prior to the "shooting" plot of the Colorado National Guard described by Major Ellison, who later testified to a motive quite similar to that speculated on by the union (that is, getting the Colorado National Guard forces paid to stay in the field).[21]

The Vindicator incident and the apparent efforts to wreck a train raised tensions and provoked rumors throughout the Cripple Creek District. It was said that a shadowy vigilante organization called the Committee of 40, which was composed of "known 'killers' and the 'best' citizens," was formed to uphold law and order. The miners were said to have formed a "Committee of Safety" in response, for they feared that the Committee of 40 planned acts of violence that could be blamed on the WFM, thus creating a pretext for the union's destruction.[5]p.102-103 The National Guard stepped up its harassment, and began arresting children who chided the soldiers.[5]p.103 On December 4, 1903, the governor proclaimed that Teller County was in a "state of insurrection and rebellion"[5]p.103 and he declared martial law.[6]p.212

Sherman Bell immediately announced that "the military will have sole charge of everything..." The governor seemed embarrassed at Bell's public interpretation of the decree and tried to soften the public perception.[6]p.212 Bell was undeterred; within weeks, the National Guard suspended the Bill of Rights. Union leaders were arrested and either thrown in the bullpen, or banished.[5]p.105-106 Prisoners who won habeas corpus cases were released in court and then immediately re-arrested. The Victor Daily Record was placed under military censorship, and all WFM-friendly information was prohibited. Freedom of assembly was not allowed. The right to bear arms was suspended—citizens were required to give up their firearms and their ammunition. An attorney who dared the Guard to come and get his guns found himself confronting soldiers and was shot in the arm.[6]p.213 On January 7, 1904, the Guard criminalized "loitering or strolling about, frequenting public places where liquor is sold, begging or leading an idle, immoral, or profligate course of life, or not having any visible means of support."[6]p.214

Hoist accident in the Independence mine

On January 26, 1904, a cage full of non-union miners broke from the hoist at the Independence mine, and fifteen men fell to their deaths. The coroner's jury found that management was negligent, having failed to install safety equipment properly. The WFM echoed the accusation about negligence, while management claimed the WFM had tampered with the lift, in spite of the union having no access to the militarized property. Reportedly 168 men quit the mine.

On March 12, troops occupied the WFM's Union Hall in Victor. Merchants were arrested for displaying union posters.[6]p.215 Then the CCMOA began pressuring employers inside and outside the district to fire union miners, issuing and requiring a "non-union card" to work in the area, while the WFM took counter-measures to limit the impact.

Of the original 3,500 strikers, 300 had returned to work. There was evidence that the non-union mine operators were paying a heavy price for their actions, and the union believed that it was winning the strike.[6]p.216-218

Explosion at the Independence Depot

On June 6, 1904, an explosion destroyed the platform at the Independence train depot, killing thirteen and injuring six non-union men going to the night shift at the Findley mine. Sheriff Robertson rushed to the scene, roped off the area, and began an investigation.

Immediately after the explosion, the CCMOA and the Citizens' Alliance met at Victor's Military Club in the Armory and plotted the removal of all civil authorities that they did not control. Their first target was Sheriff Robertson. When he declined to resign immediately, they fired several shots, produced a rope, and gave him the choice of resignation or immediate lynching.[26] He resigned. The mine owners replaced him with a man who was a member of the CCMOA and of the Citizens' Alliance. In the next few days the CCMOA and the Citizens' Alliance forced more than thirty local officials to resign, and replaced them with enemies of the WFM.

Then ignoring the objections of the county commissioners, the employers called a town meeting directly across the street from the WFM Union Hall in Victor. The city marshal of Victor deputized about a hundred deputies to stop the meeting, but Victor Mayor French, an ally of the mine owners, fired the marshal. An angry crowd of several thousand gathered, and anti-union speeches were made by members of the CCMOA. C.C. Hamlin, secretary of the Mine Owners' Association, urged the people to take the law into their own hands. A miner carrying a rifle challenged Hamlin, and a single shot was fired as someone tried to disarm the miner. Then a number of people began shooting into the crowd. Five men were seriously wounded, two of them fatally. All those wounded were nonunion men.[10]p.123

Fifty union miners left the scene to cross the street to the union hall.[10]p.123 Company L of the National Guard, a detachment from Victor that was commanded by a mine manager, surrounded the WFM building, and took up positions on a nearby rooftop. US Labor Commissioner Carroll Wright sifted through conflicting accounts, and concluded that a man on the roof of the miners hall shot down at the militia, and a militiaman fired back. Then several shots came from windows in the union hall, and the troops returned fire with volleys into the union hall. After an hour of gunfire on both sides, three miners were wounded, and the men inside surrendered so that the wounded could be taken to a hospital. Soldiers searched the building and confiscated 35 rifles, 39 revolvers, and 7 shotguns.[11]p.250-251

The Citizens' Alliance and their allies then wrecked the hall, wrecked all other WFM halls in the district, and looted four WFM cooperative stores. The Victor Daily Record workforce was again arrested. The day of the explosion, all mine owners, managers, and superintendents were deputized. Groups of soldiers, sheriff's deputies, and citizens roamed the district, looking for union members. Approximately 175 people — union men, sympathizers, city officials — were locked into outdoor bullpens in Victor, Independence, and Goldfield. Food requirements were ignored until the Women's Auxiliary was eventually allowed to feed the men.[6]p.218-219

On June 7, the day after the explosion, the Citizens' Alliance set up kangaroo courts and deported 38 union members. General Sherman Bell arrived with instructions to legalize the process of deportation. He tried 1,569 union prisoners. More than 230 were judged guilty — meaning they refused to renounce the union[5]p.112 — and were loaded onto special trains and released across the state line. For all practical purposes, in a matter of days the Western Federation of Miners had been destroyed in the Cripple Creek district.[5]p.76

Deportations and expulsions of union members

Deportations and expulsions from mining camps had long been practiced by both sides of labor disputes in the western U.S., including various locals of the Western Federation of Miners and its members, anti-union vigilante groups, and military authorities.

When non-union workers were deported, it was usually unclear if such deportations were directed or sanctioned by union officials, or were done by union members acting on their own. Deportations by union members were most commonly done to individuals or small groups of strikebreakers, or new arrivals regarded as potential strikebreakers, and driven away by threats or beatings. This had been the case in 1896 in Leadville, Colorado, when the WFM local bought rifles and issued them to teams called "regulators" who patrolled incoming trains and coaches, and forcing whomever they regarded as a potential strikebreaker to leave town.[3]p.3 Forced expulsions also occurred from 1901 to 1903 in Cripple Creek.[11]p.149-150

In some cases, mine officials disliked by union members were driven out of the area under death threats. In January 1894, the manager of the Isabella mine at Cripple Creek, Mr. Locke, was captured by a large body of armed men, and made to swear that he would leave and never return without permission of the miners, and that he would not identify those who forced him to leave. Once he gave assurances, he was allowed to get on a horse and leave the district.[10]p.22 In July 1894, a group of about 20 to 40 armed men came to the Gem mine in the Coeur D’Alene district in Idaho, searching for men who had been ordered by union miners to leave the country. They found one, John Kneebone, and shot and killed him. They then forced the mine superintendent and some other mine officials to walk to the Montana state line, and made them promise never to return.[27]

While deportations by unions and union members were mostly deportations of individuals or small groups, state militias acting under martial law, as in the Coeur D'Alene district of Idaho, and at Cripple Creek, sometimes deported hundreds of union members and union sympathizers.

Perhaps the largest expulsion by the WFM was in Telluride, Colorado in July 1901, when the WFM under the leadership of union local president Vincent St. John, rounded up 88 nonunion miners - a number of others fled the area ahead of the forced expulsion - marched them to the county line and warned them never to return. Despite a guarantee of safe passage by St. John, a number of the nonunion men were severely beaten, and some shot.[11]

When the Citizen's Protective League of Idaho Springs, Colorado forced 14 WFM officers and members out of town following the dynamite attack on the Sun and Moon mine, a speaker noted in justification that the WFM had recently been doing the same thing in Cripple Creek.[11]

Cripple Creek deportations

Under martial law in 1903 and 1904, the Colorado National Guard in the Cripple Creek district would carry out deportations of union men on a large scale, and it would be done by an arm of the state government, rather than by a private group.

Governor Peabody worked with the Italian secret service and the Italian consul in Denver to expel "undesirable aliens" from mining districts.[28]

On June 8, General Bell led 130 armed soldiers and deputies went to the small mining camp of Dunnville, 14 miles south of Victor, to arrest union miners. When they arrived, 65 miners were stationed behind rocks and trees on the hills above the soldiers. One of the miners shot at the troops, who returned fire. There were 7 minutes of steady gunfire, followed by an hour of occasional gunfire. Miner John Carley was killed in the gunfight. The much better-armed soldiers prevailed, and arrested 14 of the miners. The Dunnville miners had been armed with two rifles, three shotguns, and five revolvers.[11]

Eight armed men destroyed the office and machinery of the pro-union Victor Daily Record. The WFM was blamed, even though the printers recognized Citizens' Alliance members in the wrecking party. Governor Peabody offered to cover the losses with state funds, and the paper resumed operations as an anti-union paper.

The National Guard stopped all work at the remaining union mines. This was carried out on the Great Portland mine, the Pride of Cripple Creek, the Winchester mine, and the Morgan leases at Anaconda. Miners were arrested at shift change and deported. The owner of the Portland mine filed lawsuits to challenge the mine closing, but he was stopped by stockholders who preferred a non-union mine.[6]p.220

General Bell then ordered that all aid to families left behind by the deported miners had to be channeled through the National Guard. By such means he hoped to starve them out, insuring that the miners would have no reason to return to the district. Members of the Women's Auxiliary who distributed food in secret were arrested, taken to the bullpen and intimidated, although they were not held. Over the coming weeks other incidents of intimidation, gunfire, beatings, and expulsion erased every visible trace of unionism in the district.[6]p.223-225

C.C. Hamlin, the secretary of the Mine Owners' Association, would later be elected District Attorney. When court cases were brought against mine owners, mine managers, mill owners, bankers, deputy sheriffs, and other members of the Citizens' Alliance for deporting the union men, and for beatings and destruction, Hamlin refused to prosecute any of the cases.[10]p.136-137,154

Aftermath

After decades of struggle, the leadership of the Western Federation of Miners had come to a class analysis of their circumstances. Haywood said that miners were exploited by "barbarous gold barons" who "did not find the gold, they did not mine the gold, they did not mill the gold, but by some weird alchemy all the gold belonged to them."[16]:171

The language of the Cripple Creek District Citizens' Alliance suggests that they also viewed the struggle as a class conflict. Their resolutions to Governor Peabody spoke not of prosecuting the lawless strikers, but rather of "controlling the lawless classes."[5]p.147 This view echoed that expressed by the governor when he declared martial law, declaring that such actions were taken to counter "a certain class of individuals who are acting together..."[29]

Benjamin Rastall concluded: "The strike may be summarized thus: The unions sowed class consciousness, and it sprang up and destroyed them."[10]p.163

The governor publicly allied himself with the employers' alliances, and he thanked Craig of the Denver Citizens' Alliance for the honor of receiving "membership card No. 1."[5]p.147 The governor meanwhile spoke of his supporters — in particular, donors to a "Law and Order Banquet" — as the "best element of the State." The railroads offered half-priced fare for those attending the banquet, and "business and industrial leaders flocked into Denver from all over the state" to honor Governor Peabody for "his stand on law and order."[5]p.54-55, 214-215

Harry Orchard and the Independence Depot explosion

After the explosion at the Independence Depot, the civil authorities were deposed or deported, and those who replaced them assumed WFM guilt. Nonetheless, it is generally accepted that Harry Orchard, the WFM member who for one day acted as a bodyguard to WFM President Charles Moyer, and who would later assassinate former Idaho governor Frank Steunenberg, was involved in the crime.

WFM member Harry Orchard later confessed that he placed the dynamite beneath the platform, and together with Steve Adams, another WFM member, triggered the blast with a 200-foot long wire as the train approached and men crowded on the platform to meet it. Orchard said that he had been paid to blow up the depot by the WFM leadership.[30] Orchard signed a confession to a series of bombings and shootings which had killed at least seventeen men, including the explosions at the Independence Depot and the Vindicator mine.[6]p.228

In a trial three years later, Harry Orchard would confess to having served as a paid informant for the Mine Owners Association.[4]p.119 He reportedly told a companion, G.L. Brokaw, that he had been a Pinkerton employee for some time.[6]p.228 Newspaper reporters were very impressed with his calm demeanor on the witness stand,[4]p.116 even under cross-examination. But historians still disagree about Harry Orchard's bloody legacy.

Orchard confessed to a number of murders, including the explosion at the Independence depot, and said that the WFM had paid him for the crimes. But there was circumstantial evidence and testimony implicating agents of the mine owners for the Independence explosion. Witnesses to the depot explosion saw what may have been explosive powder being carried by CCMOA detective Al Bemore from the Vindicator mine to the depot. One source reported a meeting between Bemore and Orchard the day before the explosion.[6]p.229

Orchard testified that during the Cripple Creek strike, when he thought that the union was not rewarding him enough, he had contacted railroad detective D. C. Scott and warned that some men would try to derail a train. The detectives paid him $20, and arranged safe passage for him through the National Guard lines where union men were not permitted. Orchard's contacts were Scott and K.C. Sterling, a CCMOA detective. Sterling had previously admitted the goal of blaming such violence on the Western Federation of Miners.[4]p.119,125 Orchard recalled that "[Scott] told me if I ever got into trouble with the militia to let him know."[4]p.119 Detective Scott, in fact, had taken direct orders from General Sherman Bell,[6]p.229 and Major Ellison testified that Sherman Bell had been implicated in an earlier plot to "hold up or shoot" working miners just four months prior to the Independence Depot explosion.[21]

Bloodhounds were brought in to track the perpetrators of the Independence depot explosion. As US Labor commissioner Carroll Wright noted, "Accounts differ as to the trails pursued by these hounds."[11]p.253 One account was that a bloodhound followed a scent trail from the triggering device toward the Vindicator mine, and also to Detective Bemore's house. K.C. Sterling was told via telephone of bloodhounds tracking to the Vindicator mine, and he allegedly said to call off the dogs, they were on a false scent, and he knew who the dynamiter was.[6]p.229

A.C. Cole was a former Victor high school teacher and Republican who served as secretary of the Victor Citizens' Alliance, and a second lieutenant of Company L. He testified that preparations by the Victor militia had already been underway for the anticipated "riot" in the days preceding the explosion, and that they anticipated the specific date of a significant unspecified event. He had earlier been asked to participate in creating some sort of provocation, and refused. As a result of that refusal he was dismissed from his position with the Citizens' Alliance five days before the Independence Depot explosion occurred.[6]p.230 Cole stated that most of the militia and prominent members of the Citizens' Alliance stayed at the Baltimore Hotel in Victor the night before the explosion. A militia captain exhibited excitement and anticipation when he checked arms and supplies that night before the explosion. Cole testified that "It was generally understood and freely discussed that a riot was to be precipitated."[6]P.230 Other members of the Victor militia corroborated Cole's story. Also, a sergeant in the Cripple Creek militia testified that he saw a murder committed by two Mine Owners' Association gunmen to keep someone quiet about the Independence depot explosion.[6]p.231 There was additional testimony that the mine owners had plotted the Independence depot explosion, but had not intended to take lives.[6]p.231 A couple of individuals stated, in effect, that a change of the work shift had put the non-union workers onto the depot platform at the wrong time.[6]p.229-232

Violence

The number of deaths as a result of the Colorado labor war were 2 strikers and at least 17 strikebreakers and non-union men. Another 15 strikebreakers died in a hoist accident in the Independence mine, which mine owners blamed on union sabotage, and the union blamed on poor maintenance and inadequate safety practices.

The following deaths occurred during the strikes:

- 28 July 1903 - Idaho Springs: striking union miner killed by an explosion while trying to blow up the Sun and Moon mine.

- 21 November 1903 - Cripple Creek: 2 management employees killed by an explosion at the Vindicator mine.

- 26 January 1904 - 15 strikebreakers killed in a hoist accident at the Independence mine; the cause is disputed.

- 6 June 1904 - 13 strikebreakers killed by a bomb at the Independence train depot, with at least one other miner mortally wounded.[31]

- 6 June 1904 - Victor: 2 non-union men killed by gunfire at a mass meeting.

- 8 June 1904 - Dunnville: one striking miner killed in a gunfight with troops.

Independence depot explosion

It is widely accepted by popular writers and documentarians that the WFM was guilty of bombing the Independence Depot either because Harry Orchard was a union member, or because the WFM had the obvious motive of attacking strike breakers. However, some writers and historians have raised doubts.

Elizabeth Jameson summarized her research into the question of violence,

Whether or not individual members of the Western Federation of Miners committed violent acts during the strike, violence was not union policy. It was, however, the policy of the (Cripple Creek) Mine Owners' Association, the Citizens' Alliance, and the militia.[6]p.233

In 1906 Rastall concluded in part, before Harry Orchard confessed to the bombing,

Concerning the crimes committed during the latter part of the strike so little evidence has been adduced, that judgment must, for the present, be suspended. Especially is this true since, at the time the outrages were committed, the district was completely in the hands of those who sought in every possible way to fasten the guilt upon the unions.[10]p.150-152

Rastall noted that both sides had men capable of violent crimes,

Many of the men employed as guards by the mine owners during the strike were roughs of the worst type, men with criminal records either before or since that time... there were in the employ of the Mine Owners' Association during the strike men capable of almost any crime, and that, as pointed out by the unions, these men might as logically be blamed for the overt acts of the strike as any men who could possibly have belonged to the unions.

During the strike of 1894, a reign of terror was brought about by men of criminal character, many of whom were admitted to the unions.

There were certain officers [of the WFM] who were willing to countenance and even to instigate the beating of men and the destruction of property. Would they not wink at the commission of graver crimes?

Rastall notes that,

In the train wrecking case the union attorneys succeeded in throwing a great deal of suspicion on Detectives Scott and Sterling. Charles Beckman, who had joined the Federation as a detective for the mine owners, admitted that he had been urging the commission of various overt acts, but explained that he did so simply that by working into the confidence of the right men he should be in a position to know of such plots.[10]p.153

In spite of the portrayal of the WFM as a criminal organization, writer George Suggs concluded in his book about the Colorado Labor Wars,

"...at no time did the WFM engage in armed resistance against the constituted authorities, even when their extreme harassment and provocation might have justified it."[5]p.189

However, Suggs observed that in the Cripple Creek strike, "violence against union members and sympathizers was common."[5]p.114

No clear and indisputable evidence has come to light exclusively implicating either the Western Federation of Miners, or the Mine Owners' Association and their allies, in the worst atrocities. Historians continue to debate who blew up the Independence Depot, and who paid them to do so.[32]

Harry Orchard's confession

Coinciding with J. Bernard Hogg's analysis of agents provocateurs in "Pinkertonism and the Labor Question,"[33] William B. Easterly, president of WFM District Union No. 1, testified that the only person who discussed violence at Altman WFM meetings during the strike turned out to be a detective.[6]p.229

J. Bernard Hogg also wrote of "toughs and ragtails and desperate men, mostly recruited by Pinkerton and his officers from the worst elements of the community."[34] Harry Orchard confessed that he was a bigamist, and that he had burned businesses for the insurance money in Cripple Creek and Canada. Orchard had burglarized a railroad depot, rifled a cash register, stole sheep, and had made plans to kidnap children over a debt. He also sold fraudulent insurance policies.[4]p.118-119

Earlier in the strike, Detective Scott had paid Orchard $20, provided him with a railroad pass, and sent him to Denver where he would meet Bill Haywood for the first time, and offer his services as a bodyguard for Charles Moyer. During that trip to Telluride, WFM President Moyer was arrested by the San Miguel County Sheriff.[4]p.71,119

After former Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg was murdered and evidence pointed at Orchard, Pinkerton Detective James McParland obtained Orchard's confession by threatening him with immediate hanging, and said that he could avoid that fate only if he testified against leaders of the WFM. As, apparently, in McKinney's case and the Steve Adams case, Orchard was offered the possibility of freedom and a vague promise of financial reward for implicating union officials in court, with witness coaching as part of the package.[4]p.89-92,98

Orchard's original confession has never been released.[4]p.91 Presiding judge Fremont Wood wrote that the full confession had been available to the defense attorneys, who evidently found nothing in it of value to their clients, for they did not introduce it into evidence.[35] In 1907 a comprehensive Orchard confession was published in a popular magazine, in which Orchard described using a pistol as a triggering device for explosives.[36] Shattered pistols were found at the Vindicator explosion site and the Independence Depot explosion site.[6]p.211,218 There were also some contradictions in Orchard's allegations.[4]p.119-120

Orchard named at least five WFM men as his accomplices in the crimes to which he confessed. Three of those men stood trial in five court cases, four trials in Idaho and one in Colorado. The juries were hung or returned not guilty verdicts in trials of three of the men; charges against the fourth, WFM president Moyer, were dismissed, and the fifth individual, a WFM executive board member, fled and could not be found.

Fremont Wood, the presiding judge in both the Haywood and Pettibone trials, was highly impressed by the way Orchard held up under prolonged and severe cross-examination in each trial, and believed Orchard's testimony to be true. In Wood's experience, no one could have fabricated such a convoluted story, covering many years, in many locations, and including so many different people, and withstand such thorough cross-examination without materially contradicting himself. Wood later wrote that the prosecution case did not convincingly corroborate Orchard's testimony, but that the witnesses put on by the defense actually did a better job corroborating Orchard than the prosecution had done.[37]

Orchard pleaded guilty to Steunenberg's murder, and in March 1908, Judge Fremont Wood sentenced Orchard to hang.[38] His sentence was commuted, and he lived out the rest of his life in an Idaho prison.[4]p.140 In 1952, at 86 years of age and 45 years after the Haywood trial, Orchard wrote in his autobiography that all of his confession and his trial testimony were true.[39]

Western Federation of Miners after the Colorado Labor Wars

In the Colorado Labor War, culminating in the "climatic disaster" at Cripple Creek, "the WFM suffered the total destruction of its most stalwart local and the arrest of its most prominent leaders."[3]p.87 But the Western Federation of Miners didn't die during the Colorado Labor Wars. A number of WFM miners and leaders traveled to Chicago in 1905 to help launch the Industrial Workers of the World. The Cripple Creek strike officially ended in December 1907, although for all practical purposes it had ended three years earlier.[2]