Colorado Coalfield War

The Colorado Coalfield War was a major labor uprising in the southern and central Colorado Front Range between September 1913 and April 1914. Striking began in late summer 1913, organized by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) against the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I) after years of poor working conditions. The strike was marred by targeted and indiscriminate attacks from both strikers and individuals hired by CF&I to defend its property. Conflict was focused in the southern coal-mining counties of Las Animas and Huerfano, where the Colorado and Southern railroad passed through Trinidad and Walsenburg. It followed the 1912 Northern Colorado Coalfield Strikes.[7]:331 While the entirety of the strike-related violence is also commonly called the “Colorado Coal War” and the “Colorado Civil War,” some historians use these terms only to refer to the final ten days of intense fighting at the end of April.[8][9]

| Southern Colorado Coalfield War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Coal Wars | |||||||

Colorado National Guard soldiers guarding positions outside the Ludlow Colony, 1914. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Colorado Coal miners United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) |

Colorado National Guard Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I) Baldwin–Felts Detective Agency[1] Support from: Victor-American Fuel Company[2] | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Strike leaders: Louis Tikas † John R. Lawson Support from: Mother Jones[3] |

Gov. Elias Ammons John D. Rockefeller Jr. Adjutant Gen. John Chase Lt. Karl Linderfelt Support from: John C. Osgood | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000-12,000 striking miners[4] |

Peak Strength: 75 armed detectives 695 enlisted 397 officers[4][note b] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

19+ strikers killed[5]:222–3 400+ arrests |

37+ deaths[5]:223–4 Several troops court-martialed[6][note c] | ||||||

| Total deaths, including Ludlow Massacre: 69 – 199 | |||||||

Tensions climaxed at the Ludlow Colony, a tent city occupied by about 1,200 striking coal miners and their families, in a massacre on 20 April 1914 when the Colorado National Guard attacked. In retaliation, armed miners attacked dozens of mines and other targets over the next ten days, killing strikebreakers, destroying property, and engaging in several skirmishes with the National Guard along a 225-mile (362 km) front from Trinidad to Louisville, north of Denver.[5]:197 Violence largely ended following the arrival of federal soldiers in late April 1914, but the strike did not end until December 1914. No concessions were made to the strikers.[10] An estimated 69 and 199 people died during the strike, though far fewer are officially recorded being killed by the fighting. It has been described as the "bloodiest labor dispute in American history."[11][12][note a]

Background

In 1903, the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company was taken over from its founder, John C. Osgood, by a group of Colorado-based board members and investors with the support of John D. Rockefeller. Osgood was the wealthiest Coloradan at the time, and founded the Victor-American Fuel Company later that year.[13]

Colorado Fuel and Iron's treatment of its workers degraded after its sale to John D. Rockefeller, who gave his portion of the company to his son John D. Rockefeller, Jr. as a birthday gift. The company already had a history of buying political figures and banking "graft," but Lamont Montgomery Bowers–who was hired to “untangle the mess”–caused additional issues.[14]:78[15]:3 Bowers, made chairman of the CF&I board in 1907, admitted that company had "mighty power in the entire state." Under his leadership, every employee–regardless of citizenship status–as well as company mules were registered to vote. The workers were coerced to vote for the company's interests.[14]:29 He cut the Sociological Department and embraced the idea of a hands off approach to employee management. This caused rampant dishonesty in middle management, to the detriment of the mine workers.[5]:266

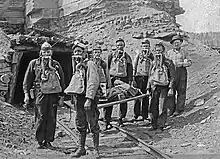

Between 1884 and 1912, Colorado's fatality rate among miners was more than double the national average, with 6.81 miners killed for every 1,000 workers (against a national average of 3.12).[16]:147 In the decade preceding the 1913-1914 Strike, CF&I mines had been involved in several major accidents.[17] These included the 31 January 1910 explosion that killed 75 at the Primero Mine[18][19] and the Starkville Mine explosion that killed 56 on 8 October of that year.[20] Both of these accidents took place in Las Animas County, part of what became the strike zone and where the Ludlow Colony was established.[17] These incidents raised the fatality rate in Colorado to above 10 deaths per 1,000 workers, three times the national average.[16]:147

In April 1912, the Northern Colorado Coalfield Strikes slowly ended following several years of striking and negotiations. This strike had seen internal tensions between different districts of UMWA miners, as some members of neighboring districts were recruited as strikebreaker, leading some members of the Industrial Workers of the World, through their publication Industrial Worker, to claim "autonomous district organization is on par with scabbery."[21]

Since the Colorado Labor Wars of 1903–1904, CF&I had spent $20,000 annually on private detectives and security to monitor and infiltrate unions. Bowers viewed these private investigators as “grafters” and sought to cut ties with them. However, local CF&I fuel manager E. H. Weitzel retained Pinkerton detectives in the southern Colorado coalfields to monitor the collective organizing of miners in the region.[14]:62–63

The Copper County Strike of copper workers in Calumet, Michigan, for nine months from 1913 to 1914, ran concurrently with the Colorado strike, and both strikers and Guardsmen were aware of the events in Michigan through coverage in Collier's and other nationally circulating publications.[22][23]

Beginning of the Strike

The Coalfield Strikes of 1913-1914 began in the late summer of 1913 when the United Mine Workers of America organized its regional District 15, led by John McLennan, to represent southern Coloradan coal field workers and put forward demands to Colorado Fuel and Iron.[11] Demands that emphasized enforcement of new regulatory laws were not met.[3][5]:266 Among the demands unheeded was the enforcement of a mine-safety bill passed in 1913 which required better ventilation in the mines, but which had no enforcement provision.[24]:127

In Southern Colorado, an expanded strike began on 23 September 1913 during a rainstorm. That day, the strike peaked with up to 20,000 miners and family members being evicted from company housing. Prior to the eviction, there had been plans to move them all into union supplied tents.[3]:266 Eight tent colonies were supposed to have been constructed with materials from the UMWA in anticipation such an eventuality, but most of the tents arrived late, leading some families to resort to using furniture as improvised shelters.[25] Despite internal statistics at CF&I that suggested only 10 percent of miners were union-members, Rockefeller was informed soon after the strike began that between 40 and 60 percent of the miners in the strike zone had left work, which became roughly 80.5 percent–7,660 men–by the 24th.[25] The day the strike was declared, Mother Jones led a march on the Trinidad town hall, giving a brief speech outside and inside:

"Rise up and strike! If you are too cowardly, there are enough women in this country to come in here and beat the hell out of you. [...] When we strike, we strike to win."

Most sheriffs and deputy sheriffs in the area were affiliated with Colorado Fuel and Iron and acted as an initial force against the strikers. Their numbers were bolstered as the strike began by recruiting of new sheriffs and deputies, including Karl Linderfelt, who later led the militia. Many of those deputized, and at least 66 in two days, were from Texas, while others were from New Mexico.[26]

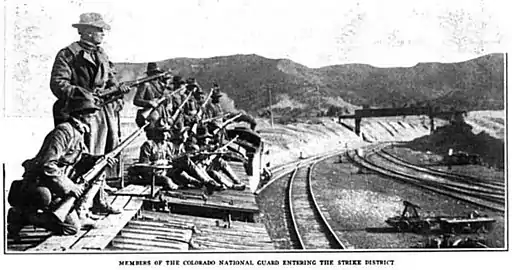

General John Chase had been the leader of the National Guard during the suppression of the 1903-1904 Cripple Creek Strike and was disposed positively towards the mine guards and hired detectives that would eventually supplement his ranks. CF&I vehicles and other infrastructure were regularly employed by the Guard for the duration of the strike. Chase, in his position at the head of the Colorado National Guard, embraced an aggressive stance against the strikers.[14]:141

Though there were strikes in places such as Walsenburg and Trinidad, the largest of the strike colonies was in Ludlow. It had around 200 tents with 1,200 miners. The escalating situation caused Governor Elias Ammons to call in the Colorado National Guard in October 1913, but after six months all but two companies were withdrawn for financial reasons. However, during this six-month period, guardsmen were allowed to leave if their primary livelihood was threatened and many of the guardsmen were “new recruits”–mine guards and strikebreakers in National Guard uniforms.[11]

As was common in mine strikes of the time, the company also brought in strikebreakers and Baldwin-Felts detectives. These detectives had experience from West Virginia strikes in which they had defended themselves from violent strikers. Balwin-Felts detectives George Belcher and Walker Belk had killed UMWA organizer Gerald Liappiat in Trinidad on 16 August 1913, five weeks before the strikes began.[5]:219[note d]

Further detectives were brought into the state once the strike commenced. Upon arrival, these between 40 and 75 detectives were deputized as county sheriffs.[14]:88–89 The Baldwin-Felts were also responsible for the recruitment of mine guards meant for service directly under CF&I.[27]

The Baldwin-Felts and CF&I had an armored car nicknamed the Death Special, which was equipped with a machine gun,[4] as well as eight machine guns purchased by CF&I from the Coal Operators' Association of West Virginia–a mining company association.[1] Three additional machine guns reached the strike zone by the end of the conflict, though how these weapons were sourced is uncertain.[26] Death Special was constructed at a CF&I shop in Pueblo for company use against their striking workers and passed on to the militia later in the conflict.[27] Prior to being distributed to the militia, company-employed detectives were accused of firing randomly into and above the miners' colonies from Death Special.[4]

The strikers also armed themselves through private sales, primarily through local private dealers. Colorado gun dealers are recorded as having sold to both sides in the various calibers that were commercially popular at the time–especially .45-70 and .22 Long Rifle.[28] Dealers in Walsenburg and Pueblo also sold explosives to both sides of the conflict, though the investigating congressional committee noted they did "not believe a majority of the people of Colorado indorse [sic] such actions."[26]

Violence early in the strike

September 1913

On 24 September, a marshal employed by CF&I named Robert Lee was attempting the arrest of four strikers accused of vandalism when he was ambushed and killed at Segundo. Another lawman later testified that Lee had been particularly hated by the strikers for his insults against their wives.[27]

October 1913

A Colorado and Southern route that connected the Front Range and passed near the Ludlow Colony began to be used as a firing position to harass strikers on 8 October 1913, resulting in no immediate casualties.[15]:3

At roughly 1:30 PM on 9 October 1913, a striking miner who had been hired as a rancher, Mark Powell,[5]:222 was herding cattle near patrolling CF&I mine guards. The guards were passing near a Colorado and Southern train bridge. A sudden burst of gunfire erupted, sending the guards to cover and killing Powell. His death came the same day four pieces of artillery arrived in the strike zone with a National Guard company. News of the incident resulted in a run on guns in Trinidad.[15]:3[14]:117

A mine in Dawson, New Mexico collapsed on 22 October, killing 263 miners. The disaster was at the time the worst mining disaster in the Western United States. It served to further raise ire amongst the miners and added perceived legitimacy to the UMWA strike just north of the Colorado-New Mexico border.[29][5]:108–109

On 24 October, a day after Governor Ammons left the strike zone, Walsenburg Sheriff Jeff Farr recruited 55 deputies. Later that day, while escorting a set of wagons belonging to a non-striking family on Seventh Street, the deputies fired into a hostile crowd, killing three foreign miners. Fearing a military response, an armed group of Greek strikers were sent by John Lawson to prevent troops from arriving in the area by the Colorado and Southern train, and they fired with little effect on it as it passed through.[14]:125–126 Lieutenant Linderfelt, one of the first deputized into the militia, then led a group of 20 militiamen to hold a section house along the railway a half-mile south of Ludlow when at 3 PM they came under fire from strikers in elevated positions on the ridges. John Nimmo, a mine guard and National Guardsman from Denver,[5]:114 was killed early in the engagement.[14]:127 A relief force of 40 militia and Baldwin-Felts arrived with a machine gun after the fighting had shifted to the multiple camps in nearby Berwind Canyon. This, coupled with a snowstorm, broke up the battle.[5]:118[30]

The National Guard was mobilized on 28 October and began field operations the next day. The next day, several buildings were set on fire in Aguilar, including a post office. The Guard later arrested several strikers in relation to this arson and handed them over to the U.S. Marshal Service.[28]

November 1913

After an agreement between General Chase and John Lawson, on 1 November the National Guard marched between the mines and tent colonies to effect a disarmament on both sides. The military report of the incident records a warm reception by the strikers, especially those at Ludlow who created a band to herald the arrival of soldiers, though the National Guard only received a reported 20-30 weapons, including a toy gun.[28]

On the morning of 8 November, at the Oakview Mine, in the La Veta Pass and near the pro-union town of the same name, pro-union men began harassing "scabs"–non-striking and strikebreaking miners. William Gambling rejected offers to join the union on his way to the local dentist and, returning in a mail carrier's car with three CF&I company men, was ambushed. Gambling was the only survivor. The militia rounded up several men after finding a pile of repeating rifles.[14]:140 Also that morning, strikebreaker Pedro Armijo was being escorted through a crowd of strike-supporters when he was shot in the head. The bullet wounded striker Michele Guerriero, who lost an eye and was arrested by the militia, who held him for three months on suspicion of knowing who fired the bullet.[5]:129 Later that day, the National Guard reported that strikers assaulted Herbert Smith, a clerk working at the McLaughlin Mine. The Military Commission held three to four men in relation to the Smith attack before releasing them to civil authorities.[28]

The National Guard reported that on 18 November the Piedmont home of Domenik Peffello, a miner who had quit the strike, was dynamited.[28] Peffello likely lost his home after returning to it upon abandoning the Piedmont tent colony.[16]:250

Baldwin-Felts detective George Belcher was killed by Italian striker Louis Zancanelli in Trinidad on 22 November in what the National Guard's official report deemed an assassination.[28] Zancanelli was sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder, though this conviction was overturned in 1917 when the trial was determined to be improperly judged.[14]:323, 340

December 1913

Mine guard Robert McMillen was shot and killed at Delagua, a mine owned by Colorado's second-largest coal company, Victor-American Fuel Company, and which had been one of the first mines to go on strike, on 2 December.[16]:247[5]:223[31]

On 17 December, the National Guard, under orders from Gov. Ammons from 1 December, allowed for the strikebreakers to resume entering the strike zone following a brief moratorium on any workers other than those already present in Southern Colorado working.[28]

January 1914

The return of Mother Jones to Trinidad on 11 January resulted in considerable response. She was arrested shortly thereafter by the National Guard on the orders of Gov. Ammons and taken to San Rafael Hospital.[28] She would be held for nine months.[15] Strikers attempted to liberate Jones on the 21st by marching on the hospital but failed to secure her release.[28]

On 27 January, the National Guard reported discovering an unexploded bomb near their camp at Walsenburg, estimating that it could have killed many of the troops stationed there. The Guard used this incident, which resulted in new arrests, as evidence of striker aggression towards the military in the region.[28]

The same day, the United States House Committee on Mines and Mining opened an investigation on both the Northern and Southern Colorado Coalfield strikes, as well as the Calumet strike. The report pertaining to the Southern Colorado strike was released on 2 March 1915.[26]

Events before Ludlow

Due to the influence of the Colorado National Guard and Greek Union leaders, such as Louis Tikas in Ludlow Colony, the strike had become relatively peaceful by the beginning of 1914. The strikers and the Guardsmen sat opposite each other at Ludlow, with brown tents for the soldiers appearing on the opposite side of the track from the white ones belonging to the colonists starting in November 1913.[32]

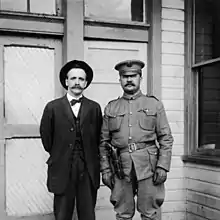

There was still tension, though, and on 14 January Linderfelt was accused of hitting Tikas while at Ludlow in retaliation for Tikas not divulging the whereabouts of a boy related to an incident in which Linderfelt and his men ran into barbed wire on a path. The official report by the National Guard detachment commander at Aguilar to General Chase on 18 January denied the claim, as did a telegram to Governor Ammons sent personally from Linderfelt.[33][34] Lawson, however, asserted in a telegram to Gov. Ammons that Linderfelt had used the "vilest of language" towards the boy in question and had said to the strikers "I am Jesus Christ, and my men on horses are Jesus Christs, and we must be obeyed." Lawson also suggested Linderfelt had acted with the intention of provoking the strikers to violence.[34]

Forbes Colony Murder

On March 8, 1914 the body of a strikebreaker, Neil Smith, was found on the train tracks near the Forbes tent colony, located near the then-emptied company town of the same name, an incident that occurred as a congressional committee was touring the area. The National Guard claimed that the colony harbored the murderers and was "so established that no workmen [could] leave the camp at Forbes without passing along or through" the colony.[28] In retaliation, the Guard destroyed the colony on 10 March, burning it to the ground while most inhabitants were away and arresting all 16 men living in the tents, an action that indirectly resulted in the deaths of two newborn children.[16]:270

Battle and Massacre at Ludlow

On the morning of April 20, 1914, the day after the Eastern Orthodox Church's Easter Sunday and after months of increased tension between the armed factions, the Ludlow Massacre occurred. On Sunday, 19 April, it was reported that a group of union-aligned women playing baseball at Ludlow exchanged insults with National Guardsmen, one of whom is reported as saying to the women, "Go ahead, have your good time to-day, and to-morrow we will get your roast."[25] On the morning of 20 April, Tikas was summoned by soldiers claiming a woman sought to speak to her husband, a supposed resident of the Ludlow Colony. Tikas refused the initial invitation to meet in the soldiers' tent. Major Patrick Hamrock, the Irish-born leader of the "Rocky Mountain Sharpshooters" and a veteran of the Wounded Knee Massacre,[14]:213 persuaded Tikas to meet at the Ludlow train stop. Tikas told his agitated fellow Greek strikers to remain calm.[25]

Sensing the militia's intent to act that day after seeing machine guns placed above the colony and choosing to disobey Tikas, strikers took cover in hastily constructed fire positions.[14]:214–215[35] Accounts of who fired the first shot differ, but fighting began or escalated after the militia at Ludlow detonated warning charges to notify Linderfelt's troops stationed at Berwind Canyon and another detachment at Cedar Hill.[7]:220[14]:216 By 9:30 AM, the gunfire had begun to reach its peak intensity.[14]:217 Families of the strikers sought shelter in cellars beneath their tents as the fighting raged through the morning and until past 5 PM.[14]:221 National Guardsmen fired a machine gun from Water Tank Hill, an elevated position above the colony that had served as an observation post for much of strike.[36] A twelve year old, Frank Snyder, left his shelter and was hit by a bullet that removed much of his head, killing him instantly. National Guardsman Pvt. Martin was fatally shot in the neck.[16]:2 In total, some 177 militia and soldiers participated in the fighting.[14]:221

A pumpman for the Colorado & Southern train that passed through the town named M. G. Low helped use a train engine to protect some of those fleeing the battle and directed them towards cover.[14]:217 At the end of the battle, a fire began and the colony burnt down. Tikas and other strikers were found shot in the back, along with others killed in the combat. Eleven children and two women were found suffocated by smoke in one of the subterranean cellars. All together, at least 18 of the union side had been killed, while Martin is the only confirmed casualty from the Guard.[16]:2, 222–223 During the 1915 Commission on Industrial Relations Congressional hearings on the massacre, Rockefeller maintained that he was not aware of any animosity among the deputized militia subsidized by CF&I, nor that had he ordered the massacre, despite accusations to the contrary from activists including Margaret Sanger.[37][38]

The 10-Day War

The news of the massacre soon reached the other tent colonies, including the large group of strikers in Walsenburg. The response was an decentralized expedition throughout Southern and Central Colorado known as the "Ten Days War."[1] At this point the union made an official "Call to Arms",[1] a departure from their previous policy of suppressing violence on the part of the strikers. This led to widespread violence across the Southern Colorado Coalfield area, unlike the small pockets of violence that occurred in canyons in the early days of the strike.[15]:3–4, 6

Popular opinion began to side with the miners. Newspapers that had previously sided with the company and Ammons, such as the Daily Camera and Rocky Mountain News, began to sympathize with the strikers and blame "dilly-dallying" on Ammons' part for the deaths.[14]:244–245

Strikers sought revenge on non-striking miners, attacking Southwestern Mine Co.'s Empire Mine on Wednesday, 22 April, only to relent after a 21-hour siege. Armed strikebreakers killed two strikers at the loss of the mine's superintendent. A minister named McDonald from nearby Aguilar heard the fighting and rightly fearing the strikers intended to kill all those at the Empire Mine. He and the Aguilar mayor negotiated a ceasefire that resulted in the strikers withdrawing.[5]:186[14]:248–249 However, before the siege broke, national news outlets began erroneously reporting that the families trapped in the Empire Mine were likely suffocated.[39] Three mine guards were killed at Delagua, where four attempts were made by strikers to take the town, and another was killed at Tabasco.[5]:189[39]

By the evening of the 22nd, Lt. Gov. Fitzgarrald was attempting to secure a ceasefire through UMWA's influential Denver lawyer Horace Hawkins. The following day, John McLennan, the president of UMWA District 15 when the strike was declared, was arrested by militia at the Ludlow stop on his way from Denver to Trinidad. Hawkins made a ceasefire conditional on McLennan's release, which was secured. Despite union anger at Hawkins for negotiating, they observed the truce along what had become a 175 miles (282 km) front.[5]:190

At midnight on 22 April, a call went out for all National Guardsmen to head for the strike zone. Chase had claimed prior to Ludlow that he was able to muster 600 men to return to the field at a moment's notice, yet only 362 men reported for duty. Seventy-six soldiers of Troop C–nicknamed "Chase Troop" as two of the general's sons along with other family members were part of the unit–mutinied, as they had been forced to stay in an uncomfortable Guard armory since returning from their initial deployment to the strike zone. Troop C did not return to coalfields for the duration of the conflict. Two 3 inches (76 mm) field guns and 220 rounds of shrapnel shells were brought with the 23-car train of 242 soldiers going south from Denver on 23 April.[5]:189 Empty carts were attached to the front of the engines to protect against dynamite traps.[14]:247 A group of pro-strikers sought to deliver weapons by car before Chase's troops arrived in Walsenburg and, despite delays, managed to bring guns and ammunition to the strikers before the train full of troops reached the strike zone. The newly arrived troops were then spread out in attempts to bring the region under their control.[14]:248–249

Through the day on 25 April the Chandler Mine near Canon City was fired upon. A non-striking miner was killed and a mine guard seriously injured before National Guardsmen arrived.[14]:258 Most of the civilian population of Walsenburg fled as sporadic violence began to overrun the city. Striking Greek miners, dissatisfied with a perceived lack of response from union officials to Ludlow, began organizing guerrilla attacks in the town and attacked the McNally Mine located nearby, killing one.[14]:259–260

A sit-in by over a thousand members of the Women's Peace Association–led by Alma Lafferty, Helen Ring Robinson, and Dora Phelps–paralyzed the Capitol building on 25 April.[14]:251[24] These women forced a "drawn and haggard" Ammons to send a request for U.S. President Woodrow Wilson to send federal troops to the strike zone.[16]:279–281

The northernmost battle took place on 28 April at the Hecla mine in Louisville. The mine was owned by the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company, which had hired the Baldwin-Felts to help protect its property between Denver and Boulder.[40] During the ten-hour battle, Captain Hildreth Frost led a small contingent of troops that had been among those rotated off the southern front. Several mine guards were seriously injured during the fighting.[5]:197

On 28–29 April, the National Guard fought strikers in the Battle of Walsenburg for control of the town and the hogback which overlooked it. Two strikers were killed on the 28th, including one by friendly fire. Colonel Verdeckerg, who was placed in command of the Guard at Ludlow following the massacre, was ordered by Chase to take 60 men to Walsenburg to retake the town on the morning of the 29th.[5]:206 Verdeckberg was ordered to hold the town until federal troops arrived then retire back.[14]:266 Several men of this detachment–Lieutenant Scott, Private Wilmouth, and Private Miller–were wounded by gunfire in the afternoon, while Walsenburg-native and medic Major Pliny Lester was killed tending to either Scott[5]:207–208 or Miller.[14]:266 At 5 PM that day, an unarmed pro-union man named Henry Llyod on a motorcycle was killed by strikers in an incident of mistaken identity.[5]:206, 222

Part-owner John D. Rockefeller, Jr. refused President Wilson's offer of mediation, conditioned upon collective bargaining, leading Wilson to exert pressure on Ammons and other elected officials in Colorado and threaten to deploy federal troops. The Mexican Revolution meant that any deployment of an already reduced and largely deployed Army would be a risky move.[14]:253 Earlier in April, the Tampico Affair had raised tensions and on 22 April U.S. sailors fought the Mexican military at the Battle of Veracruz. On 28 April, Wilson spoke with Secretary of War Lindley Garrison and ordered the Department of War to begin moving units towards Colorado while preparing to federalize National Guard units.[14]:257 Wilson would invoke the Insurrection Act of 1807 the same day for the first time since 1894 and for only the ninth time since the law's enactment.[41]:208 Garrison's stated goal for the federal troops was to "preserve [...] an impartial attitude." Only after this intervention to disarm did the war end.[16]:282

On 29 April, Lawson issued an order for remaining armed miners to stand down.[42] On 2 May, a proclamation from Garrison was issued, stating that "all persons 'not in the military service of the United States'" were to disarm, although this statement was understood as only disarming the strikers, as Wilson had received assurances from Ammons that the militia was withdrawing and did not need to turn over their weapons.[43]

The strike continued until the union ran out of funds in December 1914. While Wilson succeeded in bringing order to the situation, he demonstrated support for the labor union and the miners' unconditional surrender to the companies was seen as a defeat for Wilson.[10]

Aftermath

Theodore Roosevelt, Letter to Rep. Edward P. Costigan.[15]

Fatalities during the strike are generally assumed to be under-reported, as Las Animas County coroner's office reports more bodies related to the strike than appear in contemporary news reports.[5]:119 The office recorded 232 violent deaths from the beginning of 1910 to March 1913 with only 30 deaths resulting in a trial, which a later congressional committee would claim demonstrated a pattern of disinterest in recording fatalities associated with the mining companies. It has been suggested that this policy of under-reporting deaths in deference to the mining interests continued during the strike's violence.[26] Modern and contemporary estimates of fatalities vary widely, but following the Ludlow Colony's destruction an estimated 30 strikebreakers, National Guard, and mine guards were killed while a handful of pro-union fighters are reported to have died.[16]:278–279[5]:222–223 Clara Ruth Mozzor–a social worker who would later become the first female Assistant Attorney General of Colorado–wrote for International Socialist Review in 1914 that "waste and ruin, death and misery were the harvest of this war that was waged on helpless people. Mothers with babies at their breasts and babies at their skirts and mothers with babies yet unborn were the targets of this modern warfare."[44][note f]

Six mines and several company towns, including the abandoned Forbes, were damaged or destroyed.[16]:279 The Associated Press estimated the financial cost of the strike at $18 million (equivalent to $459,448,505 in 2019). CF&I lost $1.6 million with $5.6 million still on hand, while the UMWA spent $870,000.[16]:283–285 By 1915, CF&I mines had reached 70 percent of their pre-strike outputs.[16]:282

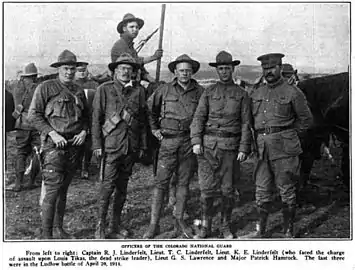

Major Patrick Hamrock and Lieutenant Karl Linderfelt were tried in independent court-martials from the rest of the National Guard and militia involved in the suppression of the strike, as they faced additional charges of assault with a deadly weapon in relation to the deaths of strikers in custody at Ludlow, including Tikas. Hamrock was charged on 13 May 1914 with arson, manslaughter, and murder, for all of which he pleaded not guilty.[45] Linderfelt admitted to striking Tikas with his Springfield rifle. The military court found Linderfelt guilty of the assault on Tikas, "but attach[ed] no criminality" to his actions.[14]:285–287

In a Trinidad court, John Lawson was found guilty of murdering Nimmo by Judge Granby Hillyer in 1915 and sentenced to life imprisonment.[46] The UMWA maintained Lawson's innocence,[47] and his conviction was overturned by the Colorado Supreme Court in 1917.[48] Of the 408 strikers charged with a crime–many with murder–there were four convictions. All four were overturned on technicalities.[14]:340 Four men charged in relation to Major Lester's death were acquitted following their trial being moved from Huerfano County to Castle Rock in Douglas County.[14]:323

Pro-union publications lamented the failure to secure immediate significant structural change in the relationship between miners and the CF&I and criticized the Guard and militia's response and actions at Ludlow.[49] The UMWA purchased a 40-acre lot that contained the Ludlow Colony and some of the land around it and began work on the Ludlow Monument at the site in 1916. It was dedicated in 1918.[50] Frank Hayes, UMWA President from 1917 to 1919 and Lieutenant Governor of Colorado from 1937 to 1939, wrote a song in tribute to the striking miners entitled "We're Coming, Colorado" set to the tune of "Battle Cry of Freedom."[51]:290[52] Folk musician Woody Guthrie released "Ludlow Massacre" in 1944.[53]

Three years after the 10-Day War, on 27 April 1917, a Victor-American Fuel Company mine in Hastings, near the former Ludlow camp, caught fire, killing 121 miners.[54] They are commemorated by a marker nearby the monument to the victims of the Ludlow Massacre. Victor-American mines had been targeted during the strike, and some were destroyed during the last week of April 1914.[55]

Rockefeller hired future Canadian prime minister Mackenzie King in June 1914 to help create a system by which miners could have internal representation within CF&I.[56][57] Rockefeller also hired Ivy Lee, an early practitioner and pioneer of public relations, and met with Mother Jones, which resulted in Rockefeller and King taking a tour of the CF&I mining communities in 1915.[58][59] These efforts would evolve into the Colorado Industrial Plan, better known as the Rockefeller Plan and the archetype for employee representation plans, as well as the creation of a CF&I company union. Through his connections with the YMCA, Rockefeller sought to encourage moral reform and provide social services that would support the miners, resulting in the YMCA creating a Mining Department and building a branch in Pueblo to serve the workers at the CF&I Minnequa steel mill there.[58] In 1917, CF&I board chairman Lamont Montgomery Bowers took over the company at the behest of Rockefeller.[60]

In 1971, Mary T. O'Neal published the only eyewitness account of the Ludlow Massacre.[61][62] The conflict has also inspired many academic histories, including The Great Coalfield War by South Dakota Senator and 1972 presidential candidate George McGovern, co-authored with Leonard Guttridge, and published the same year as the former's presidential run.[63] Controversial historian Howard Zinn said Ludlow and the strike were “the culminating act of perhaps the most violent struggle between corporate power and laboring men in American history."[64] In 1997, field work began on the University of Denver's Ludlow Massacre Archaeological Project, with research from the program published in multiple academic mediums.[65]

On 19 April 2013, Colorado governor John Hickenlooper signed an executive order creating the Ludlow Centennial Commemoration Commission in preparation for the hundredth anniversary of the Massacre a year later.[66][67] A Greek Orthodox Easter service at the memorial site took place on 20 April 2014.[68]

Following the killing of George Floyd in May 2020–among other instances of U.S. police officers killing and injuring African-Americans–widespread protests and civil unrest erupted in major U.S. metropolitan areas. The resulting riots and acts of anti-police violence led the Colorado Springs Gazette editorial board to call for the invocation of the 1807 Insurrection Act, favorably citing its usage in the Colorado Coalfield War.[69]

See also

Notes

- ^ a. The Battle of Blair Mountain, also involving the Baldwin-Felts and UMWA, is considered the largest labor uprising in the U.S. by number of combatants.

- ^ b. All but two companies of militia and Guardsmen–composed largely of mine guards–withdrawn after six months because of budgetary constraints.[4]

- ^ c. Lt. Linderfelt was convicted of assault for beating Tikas the day of the massacre.

- ^ d. Belcher would later be killed during the strike, most likely by Louis Zancanelli.[5]:219

- ^ e. The Zanetell family's furnishings from the Forbes Colony survive on permanent display in the Colorado History Museum.[70]

- ^ f. Mozzor was at her admittance to the bar in 1915 the youngest woman lawyer in Colorado and in 1917 became the first woman to serve as Assistant Attorney General of any US state.[71][72]

Footnotes

- F. Darrell Munsell (2009). "The Ten Days' War". From Redstone to Ludlow: John Cleveland Osgood's Struggle against the United Mine Workers of America. University Press of Colorado. pp. 256–276. ISBN 9780870819346. Retrieved Oct 29, 2019.

- Doesch, Ethan (6 March 2009). "Review: From Redstone to Ludlow: John Cleveland Osgood's Struggle against the United Mine Workers of America". Economic History Association. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- Boor Tonn, Mari (2011). ""From the Eye to the Soul": Industrial Labor's Mary Harris "Mother" Jones and the Rhetorics of Display". Rhetoric Society Quarterly. 41 (3): 231–249. doi:10.1080/02773945.2011.575325. JSTOR 23064465. S2CID 144700584.

- Walker, Mark (2003). "The Ludlow Massacre: Class, Warfare, and Historical Memory in Southern Colorado". Historical Archaeology. Springer. 37 (3): 66–80. doi:10.1007/BF03376612. JSTOR 25617081. S2CID 160942204.

- Martelle, Scott (2007). Blood Passion: The Ludlow Massacre and Class War in the American West. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4419-9.

- Bovsun, Mara. "Justice Story: Women, kids killed in bloody 1913 Ludlow Massacre during coal strike". Retrieved Oct 31, 2019.

- Papanikolas, Zeese. Buried Unsung: Louis Tikas and the Ludlow Massacre. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1982. bib., illus., index.

- "Topics in Chronicling America - Colorado Coalfield War". Newspaper & Periodical Reading Room. Library of Congress. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Seligman, Edwin R. A. (5 November 1914). "Colorado's Civil War and Its Lessons". Frank Leslie's Weekly. Accessible Archives. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Heckscher, August (1991). Woodrow Wilson. Easton Press. p. 330.

- "Colorado Coal Field War Project". Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Larsen, Natalie (12 June 2018). "The Colorado Coalfield Strike of 1913-1914". Intermountain Histories. Charles Redd Center for Western Studies at BYU. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Historic Resources of Redstone, Colorado and Vicinity" (PDF). 9 July 1989. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- McGovern, George Stanley; Guttridge, Leonard F. (1972). The Great Coalfield War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0395136490. OCLC 354406.

- Sunseri, Alvin (1972). "The Ludlow Massacre: A study in the mis-employment of the National Guard". University of Northern Iowa. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Andrews, Thomas G. (2010). Killing for Coal. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-73668-9. OCLC 1020392525.

- Gerald Emerson Sherard (2006). Pre-1963 Colorado mining fatalities (Report). p. 1. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Hellmann, Paul T. (14 February 2006). Historical Gazetteer of the United States. Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 1-135-94859-3.

- Mitchell, Karen. "Primero Mine". Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "1910 Explosion at the Starkville Mine Killed 56 Men". The Denver Post. 24 August 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "COLORADO COAL MINERS" (PDF). Industrial Worker. 4 (3). Marxists.org. 11 April 1912. p. 3. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Sullivan, Mark, ed. (7 February 1914). "The Issues at Calumet". Collier's. 52 (21).

- "CAPTAIN HILDRETH FROST PAPERS". Western History and Genealogy. The Denver Public Library. p. FF11. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- Andrews, Gail M. (2012). Colorado Women: A History. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-1-60732-207-8. OCLC 1100957691.

- DeStefanis, Anthony Roland (2004). "Guarding capital: Soldier strikebreakers on the long road to the Ludlow massacre". Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. The College of William & Mary. doi:10.21220/s2-d7pf-f181. S2CID 198026553.

- House Committee on Mines and Mining, 63rd United States Congress (2 March 1915). Report on the Colorado strike investigation made under House resolution 387, sixty-third Congress, third session (Report). Government Printing Office.

- West, George P. (1915). Report on the Colorado Strike (Report). United States Commission on Industrial Relations.

- Colorado Adjutant General's Office (1914). The Military Occupation of the Coal Strike Zone of Colorado by the National Guard, 1913-1914 (Report).

- Sharpe, Tom (Oct 13, 2013). "Remembering the Dawson mining disaster, 100 years later". The New Mexican. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Hart, Steve; Osterhout, Shannon (15 June 2014). "2014 Mining History Association Tour: Historic Coal and Coking Camps - Starkville, Cokedale, Boncarbo, Berwind Canyon, Hastings, and Ludlow". mininghistoryassociation.org. Mining History Association. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "Death at Delagua". World Journal. Huerfano, Las Animas. 15 November 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- Boughton, Edward J. (2 May 1914). Ludlow, Being the report of the special board of officers appointed by the governor of Colorado to investigate and determine the facts with reference to the armed conflict between the Colorado National Guard and certain persons engaged in the coal mining strike at Ludlow, Colo., April 20, 1914 (Report). Denver: Williamson-Haffner Co.

- P.J. Hamrock. Report, Aguilar, Colorado., January 18, 1914 (Report).

- K. E. Linderfelt (January 1914). Report, Berwind, Colo (Report).

- Simmons, R. Laurie; Simmons, Thomas H.; Haecker, Charles; Siebert, Erika Martin (May 2008). "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Ludlow Tent Colony" (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 41–42.

- "Water Tank Hill". The Colorado Coalfield War Archaeological Project. University of Denver. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "In the Hot Seat: Rockefeller Testifies on Ludlow". The New York Times. 21 May 1915. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "Cannibals". The Woman Rebel. The Public Papers of Margaret Sanger: Web Edition. May 1914. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "30 BESIEGED IN MINE MAY BE SUFFOCATED; Mouth of Slope Blocked by Dynamite Explosions Caused by Strikers". The New York Times. 23 April 1914. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Conarroe, Carol, The Louisville Story. Louisville, CO: Conarroe, 1978.

- Laurie; Cole (1997). The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders, 1877–1945. Washington: Center of Military History, United States Army.

- Fourteenth Biennial Report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the State of Colorado 1913-1914 (PDF) (Report). Bureau of Labor Statistics. 1914. p. 204. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "MUST SURRENDER COLORADO ARMS". The New York Times. New York Times Archive. 3 May 1914. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- Mozzor, Clara Ruth (June 1914). "Ludlow". The International Socialist Review. 14: 722–724.

- "MILITIA ACCUSED OF CRIMES". Press Democrat. Santa Rosa, California. 14 May 1914. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "FIND LAWSON GUILTY OF STRIKE MURDER; Labor Leader Gets Life Imprisonment for Killing of Deputy Sheriff in Colorado. JURY OUT SINCE SATURDAY Labor Unions Defended Prisoner, Who Is a Member of Executive Board of United Mine Workers". The New York Times. May 3, 1915. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "BAR JUDGE HILLYER, WHO TRIED LAWSON; Colorado Supreme Court Prevents Him from Presiding at Future Labor Trials. LEADER MAY GET AN APPEAL Higher Court Will Review His Case on Its Merits ;- Big Victory for Mine Workers". The New York Times. August 18, 1915. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "Conviction of John R. Lawson Set Aside by Colorado Supreme Court". Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen's Magazine. Vol. 63. 1917. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Eastman, Max (June 1914). "CLASS WAR IN COLORADO". The Masses.

- Larkin, Karin. "Decolonizing Ludlow: A Study in Public Archaeology" (PDF). p. 15. Retrieved Oct 30, 2019.

- Lewis, Ronald L. (2008). Welsh Americans: A History of Assimilation in the Coalfields. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807887905. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "Colorado Coalfield War 1913-14" (PDF). College of Charleston. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Mintz, S.; McNeill, S. (2018). ""Ludlow Massacre" By Woody Guthrie". Digital History. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Clare Vernon McKanna (1997). Homicide, Race, and Justice in the American West, 1880-1920. University of Arizona Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8165-1708-4.

- Clements, Eric L. (2017). "The One-Chance Men: The Hastings Mine Disaster of 1914" (PDF). Colorado Heritage. History Colorado: 19. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Hennen, John (2011). "Reviewed Work: Representation and Rebellion: The Rockefeller Plan at the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, 1914-1942 by Jonathan H. Rees". The Journal of American History. 97 (4): 1149–1150. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaq129. JSTOR 41508986.

- Chernow, Ron (1998). Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller Sr. Random House. pp. –571–586. ISBN 0-6794-3808-4.

- Henry, Robin (2014). "In Order to Form a More Perfect Worker". In Montoya, Fawn-Amber (ed.). Making an American Workforce: The Rockefellers and the Legacy of Ludlow. University of Colorado. pp. 81–102. ISBN 9781607323099. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- Watson, William E.; Jr, Eugene J. Halus (25 November 2014). Irish Americans: The History and Culture of a People: The History and Culture of a People. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610694674 – via Google Books.

- Smith, Gerald (17 December 2015). "Bowers worked with Rockefeller, left legacy in Broome". pressconnects. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Gluck, Sherna Berger (1974). "Mary Thomas O'Neal, audio interview". Scholarship @ the Beach: The CSULB Digital Repository. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- "Thomas (O'Neal), Mary (audio interview #1 of 2)". California State University Long Beach. 1974. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- "The Great Coalfield War". Kirkus. May 15, 1972. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- "100th Anniversary of the Ludlow Massacre". Zinn Education Project. 19 April 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Ludlow Massacre Archaeological Project Celebrates 20th Anniversary". du.edu. University of Denver. 2017. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- "Gov. Hickenlooper Creates Ludlow Centennial Commemoration Commission". VoteSmart. 19 April 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Calhoun, Patricia (18 April 2013). "Ludlow Massacre centennial will be commemorated by state commission". Westword. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "Ludlow Massacre 100th anniversary service planned". The Denver Post. 2 April 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- Gazette editorial board (4 June 2020). "Colorado Springs Gazette: Local officials should not tolerate violence". Colorado Springs Gazette. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- "Obiturary: Franklin David Zanetell, Sr". Gunnison Country Times. 26 March 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Woman Prosecutor Tells How to Succeed as Lawyer". Cincinnati Commercial Tribune. January 21, 1917. p. 21. Retrieved 23 September 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "'Spirit of the West' Girl Now Colorado's Assistant Attorney General". The Pittsburgh Press. 1917-03-04. p. 67. Retrieved 23 September 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

Relevant literature

Nonfiction

- Andrews,Thomas G. Killing for Coal: America's Deadliest Labor War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

- DeStefanis, Anthony R. “The Road to Ludlow: Breaking the 1913-14 Southern Colorado Coal Strike,” Journal of the Historical Society, 12 no. 2 (September 2012): 341–390.

- Martelle, Scott. Blood Passion: The Ludlow Massacre and Class War in the American West. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2007

- Papanikolas, Zeese. Buried Unsung: Louis Tikas and the Ludlow Massacre. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1982. bib., illus., index, 331 p.

Fiction

- Kostival, Ben. The Canyons. Boston, MA: Radial Books, 2018.

- Mary Thomas O'Neal, Those Damn Foreigners. Minerva Printing & Publishing Co., 1971.