Common People

"Common People" is a song by English alternative rock band Pulp, released in May 1995 as the lead single off their fifth studio album Different Class. It reached number two on the UK Singles Chart, becoming a defining track of the Britpop movement and Pulp's signature song in the process.[1] In 2014, BBC Radio 6 Music listeners voted it their favourite Britpop song in an online poll.[2] In a 2015 Rolling Stone readers' poll it was voted the greatest Britpop song.[3]

| "Common People" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Pulp | ||||

| from the album Different Class | ||||

| B-side | "Underwear" | |||

| Released | 22 May 1995 | |||

| Recorded | 18–24 January 1995 | |||

| Studio | The Town House, London | |||

| Genre | Britpop | |||

| Length | 5:50 | |||

| Label | Island | |||

| Songwriter(s) | ||||

| Producer(s) | Chris Thomas | |||

| Pulp singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Common People" on YouTube | ||||

The song is a critique on those who were perceived as wanting to be "like common people" and who ascribe glamour to poverty.[4] This phenomenon is referred to as slumming or "class tourism".[4] The song was written by the band members Jarvis Cocker, Nick Banks, Candida Doyle, Steve Mackey and Russell Senior. Cocker had conceived the song after meeting a Greek art student while studying at the Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in London (the college and the student feature in the lyrics). He came up with the tune on a Casiotone keyboard he had bought in a music store in Notting Hill, west London.

Justin Myers of the Official Charts Company wrote, "Common People was typical Pulp – a biting satire of posh people ‘roughing it’ and acting like tourists by hanging with the "common people". Jarvis delivered his scathing putdown with glee, in an iconic music video featuring actress Sadie Frost as the posho on the receiving end of Jarvis' acid tongue."[1] Pulp first performed the song in public during the band's set at the Reading Festival in August 1994. A year later they performed it at Glastonbury Festival as the headline act. The song has since been covered by various artists. In 2004, a Ben Folds-produced William Shatner cover version brought "Common People" to new audiences outside Europe.

Inspiration

The idea for the song's lyrics came from a Greek art student whom Pulp singer-songwriter Jarvis Cocker met while he was studying at the Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design. Cocker had enrolled in a film studies course at the college in September 1988 while taking a break from Pulp. He spoke about the song's inspiration in NME in 2013:

I'd met the girl from the song many years before, when I was at St Martin's College. I'd met her on a sculpture course, but at St Martin's you had a thing called Crossover Fortnight, where you had to do another discipline for a couple of weeks. I was studying film, and she might've been doing painting, but we both decided to do sculpture for two weeks. I don't know her name. It would've been around 1988, so it was already ancient history when I wrote about her.[5]

In a 2012 question and answer session on BBC Radio 5 Live Cocker said that he was having a conversation with the girl at the bar at college because he was attracted to her, although he found some aspects of her personality unpleasant. He remembered that at one point she had told him she "wanted to move to Hackney and live like 'the common people' ". Cocker used this phrase as the starting point for the song and embellished the situation for dramatic effect, for example reversing the situation in the song when the female character declares that "I want to sleep with common people like you" (Cocker said that in real life he had been the one wanting to sleep with the girl, while she had not been interested in him).[6] Taking this inspiration, the narrator explains that his female acquaintance can "never be like common people", because even if she gets a flat where "roaches climb the wall" ultimately, "if [she] called [her] dad he could stop it all", in contrast to the true common people who can only "watch [their] lives slide out of view".

A BBC Three documentary failed to locate the woman, who, Cocker stated, could have been in any fine art course but that "sculpture" sounded better.[7] The lyrics were in part a response by Cocker, who usually focused on the introspective and emotional aspects of pop, to more politically minded members of the band like Russell Senior. Furthermore, Cocker felt that 'slumming' was becoming a dominant theme in popular culture and this contributed to the single's rushed release. Cocker said "it seemed to be in the air, that kind of patronising social voyeurism... I felt that of Parklife, for example, or Natural Born Killers – there is that noble savage notion. But if you walk round a council estate, there's plenty of savagery and not much nobility going on."[8]

In May 2015, Greek newspaper Athens Voice suggested that the woman who inspired the song is Danae Stratou, wife of Yanis Varoufakis, a former Greek Finance minister. Stratou studied at St. Martins between 1983 and 1988 and is the eldest daughter of a wealthy Greek businessman.[9] Greek newspaper Ta Nea contacted Stratou who replied that "I think the only person who knows for whom the song was written is Jarvis himself!",[10] although the London Evening Standard reported that an email exchange with Varoufakis indicated that there was truth in the rumour.[11] Katerina Kana, a Greek-Cypriot who also studied at St. Martins during that time, has claimed since 2012 that the song was about her,[12] though Cocker has not commented on this.

Composition

Cocker came up with the tune on a small Casiotone MT-500 keyboard he had bought from the Music & Video Exchange shop in Notting Hill in west London. He thought the melody "seemed kind of catchy, but I didn't think too much about it".[13] When he played it at rehearsals to the other members of the band, most of them were unimpressed; Steve Mackey said it reminded him of Emerson, Lake & Palmer's 1977 hit single "Fanfare for the Common Man".[14] Keyboardist Candida Doyle was the only member of the group who spotted the potential of the tune, saying, "I just thought it was great straight away. It must have been the simplicity of it, and you could just tell it was a really powerful song then."[15] Cocker then wrote the lyrics inspired by his time in London. The song was first performed in public during the band's set at the Reading Festival in August 1994: Cocker revealed that he had written the majority of the lyrics the night before the band's performance, and he had trouble remembering them on stage the following day.[5]

The band realised they had "written something that had slight pretensions to anthemic"[16] and wanted to find a producer that could give them a big-sounding record. Veteran producer Chris Thomas was chosen and the single was recorded in a two-week period at The Town House in London.[17] The group used all forty-eight tracks of the studio, filling them with a variety of sounds from keyboards and even a Stylophone to create the anthemic sound they were looking for: Thomas remembered that the band "were just coming up with stuff all the time, it was just trying things on here and there."[18] To keep the single at around four minutes, the final verses that begin "Like a dog lying in a corner" were omitted, although they appear on the album version. These include the peak of the crescendo where Cocker reduces to an intense whisper and describes the life of "common people".[7]

The tune bears a "very close resemblance" to the song "Los Amantes" by the Spanish group, Mecano, which came out in 1988. However, Pulp were not accused of plagiarism, despite the similarity.[19][20]

The tune also bears a "very close resemblance" to the song "Sloppy Heart" by the group, Frazier Chorus, which came out in 1987.

Music video

The accompanying music video featured an appearance from actress Sadie Frost and a dance routine improvised by Cocker on the day of shooting.[7] The video also features a homage to the "Eleanor Rigby" sequence in the animated film Yellow Submarine, with everyday people stuck in repeating loops lasting less than a second. The club scenes were filmed inside Stepney's Nightclub on Commercial Road in the East End of London. The nightclub still had its original décor, including a 1970s dance floor, and was described as a "cultural icon" when under threat of demolition in 2007.[21]

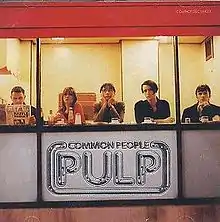

Sleeve artwork

"Common People" was released on two CD singles, one a 'day-time CD' and the other a 'night-time CD', both showing the band sitting in a café at different times of day. Four posters available on the band's 2011 tour showed a classic Pulp record sleeve, with photography notes beneath. For the poster of the "Common People" 'day-time' CD single it read:

LOCATION: Frank's Sandwich Bar, Addison Bridge Place, London W4 (eat-in and takeaway available)

TIME: 4:05pm, Wednesday 30 November 1994

PHOTOGRAPHER: Donald Milne

CAMERA: 1979 Hasselblad 500CM with 80mm lens

FILM STOCK: Fuji Super G-400 (pushed 2 stops)

DESIGN: The Designer's Republic™

ORIGINAL SLEEVE NOTES: "There is a war in progress, don't be a casualty. The time to decide whose side you're on is here. Choose wisely. Stay alive in '95."

Reception and legacy

"Common People" was a very popular song of the Britpop era with many critics praising Cocker's lyrics. The song was popular in the U.S. music press. Larry Flick of Billboard wrote: "Layered in the fabric of 'Common People' are soft keyboard threads and a majestic weave of blazing guitars. All this and witty lyrics to boot."[22] Charles Aaron of Spin considered the song to be "smarter than Blur, and slyer than Elastica." He exclaimed that "Pulp finally conquered the British charts with this exhilarating slag on class slumming."[23] He later ranked the song at number two in his pick of the singles of 1996.[24]

The song was Pulp's most popular single, and has featured on more than sixteen compilation albums since its original release. In 2006, an hour-long documentary on the song's composition and cultural impact was broadcast on BBC Three. In 2007, NME magazine placed "Common People" at number three in its list of the 50 Greatest Indie Anthems Ever. Rock: The Rough Guide said that on Different Class, Cocker was "[s]tripping away the glamour from Britpop's idealization of the working class" (it had been performed on a TV programme called Britpop Now), and described the song as the centrepiece of the album and "one of the singles of the 90s."[25] In a poll by the Triple J in July 2009, the Pulp original was placed at number 81 in their "Hottest 100 Of All Time" from over 500,000 votes cast.[26] In September 2010, Pitchfork listed "Common People" at number 2 on their list of the Top 200 Tracks of the 1990s.[27] In April 2014, listeners of BBC Radio 6 Music voted it as their favourite 'Britpop' song in an online poll conducted by the station to celebrate 20 years since the start of the Britpop era. DJ Steve Lamacq said: "It is one of the defining records of Britpop because it seemed to embrace the essence of the time so perfectly."[2] In 2014, Paste also ranked "Common People" at number one in its list of The 50 Best Britpop Songs.[28] In 2015, Rolling Stone readers voted it the greatest Britpop song in a poll.[3] As of October 2014 the single had sold 430,000 copies.[1]

Other Pulp versions

Different versions, including the recording from Pulp's headline act at Glastonbury Festival in 1995, a "Vocoda" mix and a radically different "Motiv8 club mix", also appeared on the "Sorted for E's & Wizz" singles.[29] The Vocoda mix later featured on the 2-disc version of Different Class, which was released in 2006.

William Shatner cover version

In 2004, Ben Folds produced a cover version of "Common People" for William Shatner's album Has Been that brought the song to a new audience outside of the British Isles.[30] This version begins with an electronic keyboard Britpop or disco sound, but quickly moves into a drum kit and guitar-heavy indie rock style. Reviewers were pleasantly surprised by Shatner's spoken-word presentation of Cocker's tirade against class tourism as Shatner's previous work had been widely mocked by reviewers.[30][31] Folds abruptly replaces Shatner's voice with that of singer Joe Jackson, and then alternates and blends the two into a duet, bringing along a large chorus of young voices on the line "sing along with the common people", which finally replace Shatner and Jackson's vocals in the song's concluding crescendo.

In 2011, Jarvis Cocker praised the cover version: "I was very flattered by that because I was a massive Star Trek fan as a kid and so you know, Captain Kirk is singing my song! So that was amazing."[32]

In a listeners' poll by Australian radio station Triple J, this cover version was ranked number 21 on their Hottest 100 of 2004. In 2007, a ballet called Common People, set to the songs from Has Been, was created by Margo Sappington and performed by the Milwaukee Ballet.

Other covers

UK dark wave band Libitina covered the song as "Gothic People", with subtly altered lyrics referencing clichés of the goth subculture.[33][34][35] In the Indian-themed BBC sketch show Goodness Gracious Me, a parody called "Hindi People" is sung.

Australian music-based quiz show Spicks and Specks uses five rounds of different games chosen from a large repertoire of options, each named after a well-known song. One of these is "Common People", in which each team is given three celebrities and must figure out what they have in common.

In 2007, impressionist Rory Bremner performed a version of the song, as sung by David Cameron, on the Bremner, Bird and Fortune show on Channel 4.[36] A similar version was released during the 2010 General Election by a band under the name The Common People.[37]

In February 2019 the news website Joe.ie released a speech sampled parody version of the song with the British Brexit supporting MP Jacob Rees-Mogg supposedly singing "I want to leave the Common Market" instead of "I want to sleep with common people".[38]

Track listings

All songs written and composed by Jarvis Cocker, Nick Banks, Steve Mackey, Russell Senior and Candida Doyle; except where noted.

12-inch vinyl

- "Common People" (full-length version) – 5:51

- "Underwear" – 4:05

- "Common People" (Motiv 8 Club Mix) – 7:50

- "Common People" (Vocoda Mix) – 6:18

CD single 1 / Cassette single

- "Common People" (full-length version) – 5:51

- "Underwear" – 4:05

- "Common People" (7″ edit) – 4:08

Limited edition CD single 2

- "Common People" (full-length version) – 5:51

- "Razzmatazz" (acoustic version) – 4:05

- "Dogs Are Everywhere" (acoustic version) (Jarvis Cocker, Russell Senior, Candida Doyle, Magnus Doyle, Peter Mansell) – 3:05

- "Joyriders" (acoustic version) – 3:31

Yellow 7-inch vinyl

- Released: November 1996

- "Common People" (7-inch edit) – 4:08

- "Underwear" – 4:05

Personnel

Pulp

- Jarvis Cocker – vocals, organ, acoustic guitar

- Candida Doyle – synthesizers

- Mark Webber – electric guitars

- Steve Mackey – bass guitar

- Russell Senior – violin

- Nick Banks – drums, tambourine

Additional personnel

- Anne Dudley – piano

- Chris Thomas – producer, stylophone

- Olle Romo – programming

- David 'Chipper' Nicholas – engineering

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

|

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[52] | Platinum | 600,000 |

|

| ||

See also

References

- "Official Charts Pop Gem #79: Common People". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 18 September 2019

- Michaels, Sean (14 April 2014). "Pulp's Common People declared top Britpop anthem by BBC 6 Music". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- "Readers' Poll: The 10 Best Brit-Pop Songs". Rolling Stone. 25 March 2018.

- "Pulp's Common People — railing against class tourism". Financial Times. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- "The 100 Greatest Britpop Songs". NME. London, England: IPC Media. 11 May 2013. p. 37.

- "Jarvis Cocker explains the truth behind 'Common People'". BBC Radio 5 Live. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- The Story of... Pulp's Common People (television programme). BBC Three. 14 February 2006. Archived from the original on 8 February 2006.

- Sutcliffe, Phil (March 1996). Common As Muck!. Q.

- "Is the mystery woman in Pulp's 'Common People' really Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis' wife?". The Independent.

- "Is Danea Stratou Pulp's gilr?" (in Greek). 8 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- Lo Dico, Joy (8 May 2015). "Yanis speaks up on the Common People debate". London Evening Standard. p. 16.

- "Katerina Kana" (in Greek). 4 April 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- The Story of... Pulp's Common People, 10:11 mins in

- The Story of... Pulp's Common People, 11:17 mins in

- The Story of... Pulp's Common People, 12:00 mins in

- The Story of... Pulp's Common People, 16:46 mins in

- The Story of... Pulp's Common People, 18:35 mins in

- The Story of... Pulp's Common People, 20:12 mins in

- Rate Your Music

- The Guardian

- Saini, Angela (13 April 2007). "Stepney's nightclub under threat". BBC. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- Flick, Larry (30 March 1996). "Singles". Billboard. Vol. 108 no. 13. p. 134. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Aaron, Charles (July 1996). "Singles by Charles Aaron". Spin. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- Aaron, Charles (January 1997). "Singles by Charles Aaron". Spin. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- Buckley, Jonathan; Ellingham, Mark, eds. (1996). Rock: The Rough Guide (1st ed.). Rough Guides. p. 699. ISBN 978-1-8582-8201-5.

- "Hottest 100 – Of All Time". triple j. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- "The Top 200 Tracks of the 1990s: 20–01". Pitchfork Media. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- Stiernberg, Bonnie (11 June 2014). "The 50 Best Britpop Songs". Paste. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Discography at". Acrylicafternoons.com. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. William Shatner – Has Been > Review at AllMusic

- David James Young. "William Shatner: Has Been". sputnik music.

- "Dave Haslam, Author and DJ – Official Site". Davehaslam.com. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "INTERVIEW: Libitina: Sheffield, London Gothic Band". In Music We Trust. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "The history of Libitina: 1994–1996". Libitina.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "Libitina – Gothic People". YouTube. 2 January 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Collins, Nick (8 April 2010). "General election 2010: ten top election spoofs". The Daily Telegraph. London, England: Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- "The Common People". Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- Lothian-McLean, Moya (1 February 2019). "Is the Jacob Rees-Mogg Britpop parody the best viral political video ever?". BBC Three. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- "The ARIA Australian Top 100 Singles Chart – Week Ending 15 Oct 1995". ARIA. Retrieved 6 July 2017 – via Imgur.com. N.B. The HP column displays the highest peak reached.

- "Top RPM Rock/Alternative Tracks: Issue 2890." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "Eurochart Hot 100 Singles" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 12 no. 23. 10 June 1995. p. 19. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Lescharts.com – Pulp – Common People" (in French). Les classement single. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- "Offiziellecharts.de – Pulp – Common People". GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "Norwegiancharts.com – Pulp – Common People". VG-lista. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- "Official Scottish Singles Sales Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Swedishcharts.com – Pulp – Common People". Singles Top 100. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- "Swisscharts.com – Pulp – Common People". Swiss Singles Chart. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "The ARIA Australian Top 100 Singles Chart – Week Ending 21 Jul 1996". ARIA. Retrieved 16 April 2020 – via Imgur.com.

- "Årslista Singlar, 1995" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Top 100 Singles 1995". Music Week. 13 January 1996. p. 9.

- "British single certifications – Pulp – Common People". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

Bibliography

- The Story of... Common People – Pulp. BBC Three, broadcast 14 February 2006.

- McCombe, J. (2014). “Common People”: Realism, class difference, and the male domestic sphere in Nick Hornby's Collision with Britpop. Modern Fiction Studies, 60(1), pp. 165–184. doi:10.2307/26421708