Confederate Memorial (Wilmington, North Carolina)

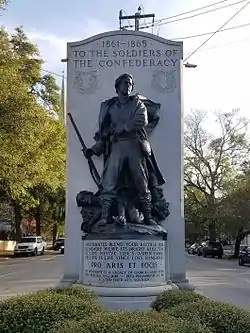

The Confederate Memorial is a monument in downtown Wilmington, North Carolina that was erected in 1924 by the estate of veteran Gabriel James Boney, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and a Confederate veterans association.[1]

The memorial, before its dismantling and covering in June 2020. Note the missing bayonet. | |

Location in North Carolina | |

| Coordinates | 34°14′03.44″N 77°56′45.2″W |

|---|---|

| Location | Wilmington, North Carolina |

| Designer | Henry Bacon and Francis Herman Packer |

| Material | Bronze and granite |

| Completion date | 1924 |

| Dedicated to | The Soldiers Of The Confederacy |

| Dismantled date | 2020 |

The monument is a 40-foot, 11-ton stele of white granite behind a granite pedestal upon which stood a bronze sculpture of two soldiers. One soldier, standing with a rifle, protects a wounded soldier holding a broken sword.

The monument, located in a narrow island in the middle of a busy street near Wilmington's downtown nightlife district, has a history of being struck by vehicles and as a target for vandals. In 2020, it became a flashpoint of civil protests against police brutality following the death of George Floyd.

In the early morning hours of June 25, 2020, the City of Wilmington removed the statue, citing public safety and protection of historical relics.[2] By June 30, the city government had covered the stele and pedestal with a black shroud, obscuring the inscriptions.[3]

The removal of the statue was coincident with the announcement by the city government that three police officers had been fired for "brutally racist" conversations recorded on official police equipment.[4]

The city government did not reveal the storage location or a date for reassembly of the monument.

Donor

Gabriel James Boney had been a soldier in Company H, 40th North Carolina Regiment during the American Civil War. He returned to Wilmington after the war and became a wealthy mill owner. He was elected a city alderman and later to the state General Assembly. He was active in a Confederate veteran's association in Wilmington. He never married and had no children.[5] Upon his death in 1915, he left $25,000 ($640,000 in 2019 dollars) to be used "for a suitable memorial to the Confederate soldier."[6]

Artists

Henry Bacon

The monument was designed by Henry Bacon, who had been the principal designer of the Lincoln Memorial.

He spent much of his youth in Wilmington and is buried there.[7]

Francis Herman Packer

The statue was sculpted by Francis Herman Packer, a native of Germany who lived on Long Island, New York and was a student of Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

A decade earlier, Packer had been hired by a United Daughters of Confederacy chapter in Wilmington to sculpt the Confederate George Davis Monument (dismantled, June 2020), located one block to the north and dedicated in 1911.[8]

Lost Cause Inscriptions

Obverse

1861–1865

To the Soldiers of the Confederacy

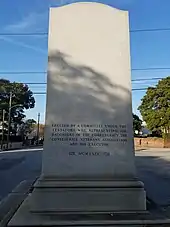

Reverse

Erected by a Committee under the

testator's Will representing the

Daughters of the Confederacy, the

the Confederate Veterans Association

and his ExecutorMCMXXIV

On the Pedestal

Confederates blend your recollections

Let memory weave its bright reflections

Let love revive life's ashen embers

For love is life since love remembers

PRO ARIS ET FOCIS

This monument is a legacy of Gabriel James Boney

Born Wallace, NC 1846 – Died Wilmington, NC 1915[9]

'Pro Aris et Focis'

The motto Pro Aris Et Focis translates from Latin as "For Altars and Hearths."[10]

The motto has been used for centuries mostly by military organizations, and is often transliterated in myth as "for God and Country." ("Pro Deo et Patria" is an equally ancient and more common Latin motto directly translated as "For God and Country.")

In the context of Lost Cause mythology, "For Altars and Hearths" is intended to place within the public memory the falsehood that the Confederacy did not fight in the American Civil War principally for the preservation of chattel slavery.[11]

Historians have argued that similar monuments erected by the UDC are pieces of a far wider national effort by the UDC and others, decades after the surrender of the confederacy, to insert the false Lost Cause Narrative into the public memory, announce to nonwhites the final defeat of Reconstruction, and to support white supremacy. [12]

Siting and Context

The monument was erected in 1924 at the northmost end of the grassy median within the 100 block of South Third Street, at its intersection with Dock Street.[13] The intersection is one block south of the historic crossroads of the city at Third Street and Market Street.

The monument marks the northern entrance to an elite neighborhood—one built, beginning in the mid-18th century, by the city's wealthiest and most powerful whites.

The nearest building, at 100 South Third Street, is the Elizabeth Bridgers House,[14] a 15,000 square foot mansion constructed in 1905 for the widowed daughter-in-law of Confederate politician Robert Rufus Bridgers.[15]

Damage and Dismantling

1954

A motor vehicle knocked the statue down. A supplier from Salisbury provided replacement granite.[16] It was repaired and re-erected on the same spot.

1980s

On an unknown date during the latter half of decade, the bayonet was damaged and replaced.[17]

1999-2000

In late 1999, a motor vehicle knocked the entire monument from its foundation and onto South Third Street. Two people were hospitalized.[18]

The foundation was cracked and the backdrop tablet was knocked over. The monument and statue were removed for repair and, where necessary, replacement with new granite.

Architect Charles Boney told the Wilmington Star-News soon after the collision that he was committed to ensuring the memorial would be repaired and then restored at its original site:

“It’s a part of my heritage and it’s a part of the city’s history, so I just want to make sure it’s fixed right.”[19]

While re-erecting the tablet at the original location, the crane fell damaging overhead power lines, parked motor vehicles and a nearby wall.[20] The monument pieces were again removed for repair and replacement. During re-re-erection in 2000, the works were again damaged. That damage was repaired and the monument restored to its original location and configuration.

2003

On an unknown date during that year, an unknown person broke off the bayonet from the rifle held by the Confederate soldier in Packer's statue, and the piece of bronze went missing. The damage went unrepaired for at least 10 years.

In 2013, a descendant relative named Gabriel James Boney said of the damage:[21]

“My father [aged 89] would love to see it put back on. It’s a priority for him.“

2019

In the early hours of July 4, an unknown person threw orange paint on the memorial.[22]

2020

In March, an unknown person placed a white flag of surrender in the statue's hands.

In early June, two unknown persons painted the words "Black Lives Matter" on the base of the statue.

That same month, during a period of declaration of a state of emergency, the city government blocked public access to the monument with traffic cones and crime scene tape.

In the early hours of June 25, the City of Wilmington removed the statue and covered the remaining tablet and pedestal, and their Lost Cause inscriptions, with a black shroud.

In September, Wilmington's mayor said that the threat to public safety that conditioned the memorial's dismantling continued. A majority of the Wilmington City Council told a journalist that the disposition of the city's Confederate monuments was not a high priority.[23]

References

- Hutteman, Hewlett Ann. Postcard History Series: Wilmington, North Carolina. Arcadia Publishing 2000. 58.

- "Wilmington Temporarily Removes 2 Confederate Monuments". Spectrum News. 25 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Photo of George Davis and Confederate Soldier Memorials in Wilmington, NC USA". starnewsonline.com. 30 June 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- The Washington Post. "Wilmington Police Officers Fired for Racist Talk." https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/06/25/wilmington-racist-police-recording/

- "Obituary Notice-Gabriel James Boney". newspapers.com. The Wilmington Morning Star. 7 January 1915. p. 5. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Louis T. Moore (4 March 1944). "The Boney Monument". digital.ncdcr.gov. North Carolina Digital Collections: The State: A Weekly Survey of North Carolina. p. 1. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- North Carolina Architects-Henry Bacon. https://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000028

- NCpedia. "Packer, Francis Herman". https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/packer-francis-herman

- Hutteman, Hewlett Ann. Postcard History Series: Wilmington, North Carolina. Arcadia Publishing 2000.

- Merriam-Webster "English Translation of 'Pro Aris et Focis'" https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/pro%20aris%20et%20focis

- Foner, Eric (2007). Reconstruction: America's unfinished revolution; 1863–1877 (1. Perennial classics ed., [Nachdr.]. ed.). New York [u.a.]: Perennial Classics. ISBN 978-0060937164.

- Brundage, W. Fitzhugh (29 October 2000). White Women and the Politics of Historical Memory in the New South. Princetown University Press. p. 115–116. ISBN 0691001936.

These women architects of whites' historical memory, by both explaining and mystifying the historical roots of white supremacy and elite power in the South, performed a conspicuous civic function at a time of heightened concern about the perpetuation of social and political hierarchies. Although denied the franchise, organized white women nevertheless played a dominant role in crafting the historical memory that would inform and undergird southern politics and public life.

- Google Maps. "South Third Street and Dock Street, Wilmington, North Carolina" https://goo.gl/maps/D2xyV5VAvEZ8fW8b9

- "Article: 'Elizabeth Bridgers House'". North Carolina Architects & Builders: A Biographical Dictionary. North Carolina State University Libraries. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "Turn of the Century Elegance." Graystone Inn. http://www.graystoneinn.com

- "Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina". docsouth.unc.edu. UNC University Library. 19 March 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina". docsouth.unc.edu. UNC University Library. 19 March 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Fallen Warrior: Car Topples Confederate Memorial at Third and Dock Streets". starnewsonline.com. StarNews Media. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "Caption in 'PHOTOS: Confederate Statues in Downtown Wilmington'". starnewsonline.com. StarNews Media. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Reiss, Cory. "Monumental Repairs." Wilmington Star-News. 1999/11/04. 1A.

- March, Julian. "Wilmington to Review Ways to Secure Statue's Bayonet". starnewsonline.com. StarNews Media. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "Downtown Wilmington Confederate Statues Vandalized". abc11.com. Wilmington, North Carolina: WTVD-TV. 5 July 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Hunter Ingram (23 September 2020). "Wilmington removed two Confederate statues in June. Three months later, law says city must decide what happens next". Wilmington, North Carolina: StarNews Media. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

Councilman Neil Anderson said it hasn’t been at the top of his mind, nor has he spoken with any of his fellow council members about it. Instead, he would prefer to hold off on those discussions right now. “Putting them back up right at this moment, anywhere, is not a priority,” Anderson said. “More of a cooling-off period is probably wise. And you have to remember that to place them anywhere, someone has to accept them.” Councilman Clifford Barnett Sr. also said he would prefer to wait on those discussions and focus on other things affecting the city. But Councilman Charlie Rivenbark said the council’s lack of action already speaks volumes. “Our silence on this is deafening,” Rivenbark said. “It’s the 800-pound gorilla in the room and no one wants to touch it.”

External links

Media related to Confederate Memorial (Wilmington, North Carolina) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Confederate Memorial (Wilmington, North Carolina) at Wikimedia Commons