Cormac McCarthy

Cormac McCarthy (born Charles Joseph McCarthy Jr.,[1] July 20, 1933) is an American novelist, playwright, short-story writer, and screenwriter. He has written ten novels, two plays, two screenplays, and three short-stories, spanning the Southern Gothic, Western, and post-apocalyptic genres. He is well known for his graphic depictions of violence and his unique writing style, recognizable by its lack of punctuation and attribution. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest contemporary writers.[2]

Cormac McCarthy | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) McCarthy in 1973 (Child of God dust jacket) | |

| Born | Charles Joseph McCarthy Jr. July 20, 1933 Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist, playwright, screenwriter |

| Genre | Southern gothic, western, post-apocalyptic |

| Notable works | Suttree (1979) Blood Meridian (1985) All the Pretty Horses (1992) No Country for Old Men (2005) The Road (2006) |

| Spouses | Lee Holleman

(m. 1961; div. 1962)Anne DeLisle

(m. 1966; div. 1981)Jennifer Winkley

(m. 1997; div. 2006) |

| Children | 2 |

McCarthy was born in Providence, Rhode Island, although he was raised primarily in Tennessee. In 1951, he enrolled in the University of Tennessee, but dropped out to join the Air Force. His debut novel, The Orchard Keeper, was published in 1965. Awarded literary grants, McCarthy was able to travel to southern Europe, where he wrote his second novel, Outer Dark (1968). Suttree (1979), like his other early novels, received generally positive reviews, but was not a commercial success. A MacArthur genius grant enabled him to travel to the American Southwest, where he researched and wrote his fifth novel, Blood Meridian (1985). Although it garnered lukewarm critical and commercial reception, it is now regarded as his magnum opus, with some even labelling it the Great American Novel.

McCarthy first experienced widespread success with All the Pretty Horses (1992), for which he received both the National Book Award[3] and National Book Critics Circle Award. It was followed by The Crossing (1994) and Cities of the Plain (1998), completing the Border Trilogy. His 2005 novel No Country for Old Men received mixed reviews. His 2006 novel The Road won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Fiction. Many of McCarthy's works have been adapted into film. No Country for Old Men was adapted into a 2007 film, winning four Academy Awards, including Best Picture. All the Pretty Horses, The Road, and Child of God have also been adapted into films, while Outer Dark was turned into a 15-minute short. McCarthy has also had a play adapted into a 2011 film, The Sunset Limited.

McCarthy currently works with the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), a multidisciplinary research center. At the SFI, he published the essay "The Kekulé Problem" (2017), which explores the human subconscious and the origin of language. His next novel, The Passenger, was announced in 2015 but is yet to be released as of February 2021.

Life

Early life

McCarthy was born in Providence, Rhode Island on July 20, 1933, one of six children of Gladys Christina (née McGrail) and Charles Joseph McCarthy.[4] His family were Irish Catholics.[5] In 1937, the family relocated to Knoxville, where his father worked as a lawyer for the Tennessee Valley Authority.[6] The family first lived on Noelton Drive in the upscale Sequoyah Hills subdivision, but by 1941 had settled in a house on Martin Mill Pike in South Knoxville (this latter house burned in 2009).[7] McCarthy would later say "We were considered rich because all the people around us were living in one- or two-room shacks."[8] Among his childhood friends was Jim Long (1930–2012), who would later be depicted as J-Bone in Suttree.[9]

McCarthy attended St. Mary's Parochial School and Knoxville Catholic High School,[10] and was an altar boy at Knoxville's Church of the Immaculate Conception.[9] As a child, McCarthy saw no value in school, preferring to pursue his own interests. McCarthy described a moment when his teacher asked the class about their hobbies. McCarthy answered eagerly, as he later said "I was the only one with any hobbies and I had every hobby there was… name anything, no matter how esoteric. I could have given everyone a hobby and still had 40 or 50 to take home."[11]

In 1951, he began attending the University of Tennessee but dropped out in 1953 to join the Air Force. While stationed in Alaska, McCarthy voraciously read books, which he claimed was the first time he had done so.[8] He also hosted a radio show.[6] He returned to UTK in 1957, where he published two stories, "A Drowning Incident" and "Wake for Susan" in the student literary magazine, The Phoenix, writing under the name C. J. McCarthy, Jr. For these, he won the Ingram-Merrill Award for creative writing in 1959 and 1960. But in 1959, he dropped out of UTK for the final time and left for Chicago.[6][8]

For purposes of his writing career, McCarthy decided to change his first name from Charles to Cormac to avoid confusion, and comparison, with ventriloquist Edgar Bergen's dummy Charlie McCarthy.[12] Cormac had been a family nickname given to his father by his Irish aunts.[8] Some sources dispute this and say his family changed it. Others say he changed his name to honor the Irish chieftain Cormac MacCarthy, who constructed Blarney Castle.[13]

After marrying fellow student Lee Holleman in 1961, McCarthy "moved to a shack with no heat and running water in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains outside of Knoxville". There the couple had a son, Cullen, in 1962.[14] When writer James Agee's childhood home was being demolished in Knoxville that year, McCarthy took bricks from the site and with them built one or more fireplaces inside his Sevier County shack.[15] While caring for the baby and tending to the chores of the house, Lee was asked by Cormac to also get a day job so he could focus on his novel writing. Dismayed with the situation, she moved to Wyoming, where she filed for divorce and landed her first job teaching.[14]

Early writing career (1965–1991)

Random House published McCarthy's first novel, The Orchard Keeper, in 1965. He had finished the novel while working part-time at an auto-parts warehouse in Chicago.[8] McCarthy decided to send the manuscript to Random House because "it was the only publisher [he] had heard of." At Random House, the manuscript found its way to Albert Erskine, who had been William Faulkner's editor until Faulkner's death in 1962.[16] Erskine continued to edit McCarthy's work for the next 20 years.[17] Upon its release, critics noted its similarity to the work of Faulkner and praised his striking use of imagery.[18][19] The Orchard Keeper won a 1966 William Faulkner Foundation Award for notable first novel.[20]

While living in the French Quarter in New Orleans, McCarthy was expelled from a $40-a-month room for failing to pay his rent.[8] While traveling the country, he always carried a 100-watt bulb in his bag so he could read at night, no matter where he was sleeping.[11]

In the summer of 1965, using a Traveling Fellowship award from The American Academy of Arts and Letters, McCarthy shipped out aboard the liner Sylvania hoping to visit Ireland. While on the ship, he met Englishwoman Anne DeLisle, who was working on the Sylvania as a dancer and singer. In 1966, they were married in England. Also in 1966, he received a Rockefeller Foundation Grant, which he used to travel around Southern Europe before landing in Ibiza, where he wrote his second novel, Outer Dark (1968). Afterward he returned to the United States with his wife, where Outer Dark was published to generally favorable reviews.[21]

.jpg.webp)

In 1969, the couple moved to Louisville, Tennessee, and purchased a dairy barn, which McCarthy renovated, doing the stonework himself.[21] The couple lived in "total poverty", bathing in a lake. DeLisle claimed, "Someone would call up and offer him $2,000 to come speak at a university about his books. And he would tell them that everything he had to say was there on the page. So we would eat beans for another week."[8] While living in the barn, he wrote his next book, Child of God (1973), based on actual events. Like Outer Dark before it, Child of God was set in southern Appalachia. In 1976, McCarthy separated from Anne DeLisle and moved to El Paso, Texas.[22]

In 1974, Richard Pearce of PBS contacted Cormac McCarthy and asked him to write the screenplay for an episode of Visions, a television drama series. Beginning in early 1975, and armed with only "a few photographs in the footnotes to a 1928 biography of a famous pre-Civil War industrialist William Gregg as inspiration", he and McCarthy spent a year traveling the South in order to research the subject matter.[23] McCarthy completed the screenplay in 1976 and the episode, titled The Gardener's Son, aired on January 6, 1977. It was also shown in numerous film festivals abroad.[24] The episode would go on to be nominated for two primetime Emmy awards in 1977.[25]

In 1979, McCarthy published the semi-autobiographical Suttree, which he had written over a period of 20 years. It was based on his experiences in Knoxville on the Tennessee River. Jerome Charyn likened it to a doomed Huckleberry Finn.[26][27][28]

In 1981, McCarthy was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, worth $236,000. Saul Bellow, Shelby Foote, and others had recommended McCarthy to the organization. At this time, McCarthy left his wife. The grant enabled him to travel to the South-West, where he could conduct research for his next novel: Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West (1985).[17] The book is well known for its violence, with The New York Times declaring it "bloodiest book since the Iliad".[22] Although initially snubbed by many critics, the book has grown appreciably in stature in literary circles; Harold Bloom called Blood Meridian "the greatest single book since Faulkner's As I Lay Dying".[29] In a 2006 poll of authors and publishers conducted by The New York Times Magazine to list the greatest American novels of the previous quarter-century, Blood Meridian placed third, behind only Toni Morrison's Beloved (1987) and Don DeLillo's Underworld (1997).[30][31] Some have even suggested that it is the Great American Novel.[32] It was also included on Time magazine's 2005 list of the 100 best English-language books published since 1923.[33] At the time, he was living in a stone cottage behind an El Paso shopping center, which he described as "barely habitable".[8]

As of 1991, none of McCarthy's novels had sold more than 5,000 hardcover copies, and "for most of his career, he did not even have an agent." He was labelled as the "best unknown novelist in America".[22]

Success and acclaim (1992–2013)

| External video | |

|---|---|

After twenty years of working with McCarthy, Albert Erskine retired from Random House. McCarthy turned to Alfred A. Knopf, where he fell under the editorial advisement of Gary Fisketjon. As a final favor for Erskine, McCarthy agreed to his first-ever interview, with Richard B. Woodward of The New York Times.[6]

McCarthy finally received widespread recognition after the publication of All the Pretty Horses (1992), when it won the National Book Award[34] and the National Book Critics Circle Award. It became a New York Times bestseller, selling 190,000 hardcover copies within six months.[6] It was followed by The Crossing (1994) and Cities of the Plain (1998), completing the Border Trilogy.[35] In the midst of this trilogy came The Stonemason (first performed in 1995), his second dramatic work.[36][37]

.jpg.webp)

McCarthy's next book, No Country for Old Men (2005), was originally conceived as a screenplay before being turned into a novel.[38] Consequently, the novel has little description of the setting and is composed heavily of dialogue.[2] The title originates from the 1926 poem "Sailing to Byzantium" by Irish poet W. B. Yeats.[39] It stayed with the Western setting and themes yet moved to a more contemporary period. The Coen brothers adapted it into a 2007 film of the same name, which won four Academy Awards and more than 75 film awards globally.[38]

In 2003, while sleeping at an El Paso motel with his son, McCarthy imagined the city in a hundred years: "fires up on the hill and everything being laid to waste". He wrote two pages covering the idea; four years later in Ireland he would expand the idea into his tenth novel, The Road. It follows a lone father and his young son traveling through a post-apocalyptic America, hunted by cannibals.[note 1] Many of the discussions between the Father and the Boy were verbatim conversations McCarthy had had with his son.[11][41] Released in 2006, it won international acclaim and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.[38] McCarthy did not accept the prize in person, instead sending Sonny Mehta in his place.[42] A 2009 film adaptation was directed by John Hillcoat, written by Joe Penhall, and starred Viggo Mortensen and Kodi Smit-McPhee. Critics were mostly favorable in their reviews: Roger Ebert found it "powerful but lacks... emotional feeling",[43] Peter Bradshaw noted "a guarded change of emphasis",[44] while Dan Jolin found it to be a "faithful adaptation of Cormac McCarthy's devastating novel".[45]

Also in 2006, McCarthy published the play The Sunset Limited. Critics noted that the play was unorthodox and may have had more in common with a novel, hence McCarthy's subtitle: "a novel in dramatic form".[46][47] McCarthy later adapted it into a screenplay for a 2011 film, directed and executive produced by Tommy Lee Jones, who also starred opposite Samuel L. Jackson.[47][48]

Oprah Winfrey selected McCarthy's The Road as the April 2007 entry in her Book Club.[2][49] As a result, McCarthy agreed to his first television interview, which aired on The Oprah Winfrey Show on June 5, 2007. The interview took place in the library of the Santa Fe Institute. McCarthy told Winfrey that he does not know any writers and much prefers the company of scientists. During the interview, he related several stories illustrating the degree of outright poverty he endured at times during his career as a writer. He also spoke about the experience of fathering a child at an advanced age, and how his son was the inspiration for The Road.[50]

In 2012, McCarthy sold his original screenplay The Counselor to Nick Wechsler, Paula Mae Schwartz, and Steve Schwartz, who had previously produced the film adaptation of McCarthy's novel The Road.[51] Directed by Ridley Scott, production finished in 2012. It was released on October 25, 2013, to polarized critical reception. Mark Kermode of The Guardian found it "datedly naff";[52] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone described it as "a droning meditation on capitalism";[53] however Manohla Dargis of The New York Times found it "terrifying" and "seductive".[54]

Santa Fe Institute (2014–present)

McCarthy has been a trustee and done considerable work with the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), a multidisciplinary research center devoted to the study of complex adaptive systems.[55] McCarthy is unique, as nearly all other members of the SFI have a scientific background. As Murray Gell-Mann explained, "There isn't any place like the Santa Fe Institute, and there isn't any writer like Cormac, so the two fit quite well together."[17] From his work at the Santa Fe Institute, McCarthy published his first piece of nonfiction writing in his 50-year writing career. In the essay entitled "The Kekulé Problem" (2017), McCarthy analyzes a dream of August Kekulé's as a model of the unconscious mind and the origins of language. He theorizes about the nature of the unconscious mind and its separation from human language. The unconscious, according to McCarthy, "is a machine for operating an animal" and that "all animals have an unconscious." McCarthy goes on to postulate that language is purely a human cultural creation, and not a biologically determined phenomenon.[56]

In 2015, McCarthy's next novel, The Passenger, was announced at a multimedia event hosted in Santa Fe by the Lannan Foundation. Influenced by his time among scientists, the unfinished book was described by SFI biologist David Krakauer as "full-blown Cormac 3.0—a mathematical [and] analytical novel". The Passenger will be McCarthy's first novel to feature a female protagonist.[20] Though the novel's release was announced for 2016, it remains unreleased as of January 2021.

Writing approach and style

Syntax

—Cormac McCarthy's polysyndetic use of "and" in No Country for Old Men

McCarthy makes sparse use of punctuation, even replacing most commas with "and" to create polysyndetons.[57] The word "and" has been called "the most important word in McCarthy's lexicon".[2] He told Oprah Winfrey that he prefers "simple declarative sentences" and that he uses capital letters, periods, an occasional comma, a colon for setting off a list, but never semicolons.[note 2][58] He does not use quotation marks for dialogue and believes there is no reason to "blot the page up with weird little marks".[59] Erik Hage notes that McCarthy's dialogue also often lacks attribution, but that "Somehow...the reader remains oriented as to who is speaking."[60] His attitude to punctuation dates to some editing work he did for a professor of English while he was enrolled at the University of Tennessee, when he stripped out much of the punctuation in the book being edited, which pleased the professor.[61] McCarthy also edited fellow Santa Fe Institute Fellow W. Brian Arthur's influential article "Increasing Returns and the New World of Business", published in the Harvard Business Review in 1996, removing commas from the text.[62] He has also done copy-editing work for physicists Lawrence M. Krauss and Lisa Randall.[63]

Saul Bellow praised his "absolutely overpowering use of language, his life-giving and death-dealing sentences". Richard B. Woodward has described his writing as "reminiscent of early Hemingway".[8] Unlike earlier works such as Suttree and Blood Meridian, McCarthy's work after 1993 used simple, restrained vocabulary.[2]

Themes

—Cormac McCarthy explaining his philosophy[11]

McCarthy's novels often depict explicit violence.[11] Many of his works have been characterized as nihilistic,[64] particularly Blood Meridian.[65] This is disputed by some, who attest that Blood Meridian is actually a gnostic tragedy.[66][67] Many of his later works have been characterized as highly moralistic. Erik J. Wielenberg argues that The Road depicts morality as secular and originating from individuals, such as the father, and separate from God.[68]

The bleak outlook of the future, and the seemingly inhuman foreign antagonist Anton Chigurh of No Country for Old Men, is said to reflect the apprehension of the post-9/11 era.[69] Many of his works portray individuals in conflict with society, acting on instinct rather than emotion or thought.[70] Another theme throughout many of McCarthy's work is the ineptitude or inhumanity of those in authority, particularly in law enforcement. This is seen in Blood Meridian with the murder spree the Glanton Gang initiates due to the bounties, the "overwhelmed" law enforcement in No Country for Old Men, and the corrupt police officers in All the Pretty Horses.[71] As a result, he has been labelled the "great pessimist of American literature".[11]

Spanish dialogue

Cormac McCarthy is fluent in Spanish, having lived in Ibiza, Spain, in the 1960s and later settling in El Paso, Texas, where he lived for nearly 20 years.[72] As a result, Spanish has appeared in many of his works. In "Mojado Reverso; or, a Reverse Wetback: On John Grady Cole's Mexican Ancestry in All the Pretty Horses", Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera observes: "John Grady Cole is a native speaker of Spanish. This is also the case of several other important characters in the Border Trilogy, including Billy Parhnam (sic), John Grady's mother (and possibly his grandfather and brothers), and perhaps Jimmy Blevins, each of whom are speakers of Spanish who were ostensibly born in the US political space into families with what are generally considered English-speaking surnames…This is also the case of Judge Holden in Blood Meridian."[73][72]

Work ethic and process

McCarthy has dedicated himself to writing full time, choosing not to work other jobs to support his career. "I always knew that I didn't want to work," McCarthy has said. "You have to be dedicated, but it was my number-one priority."[75] His decision not to work sometimes subjected him and his family to poverty early in his career.[50]

Nevertheless McCarthy has, according to scholar Steve Davis, an "incredible work ethic".[76] He prefers to work on several projects simultaneously and said, for instance, that he had four drafts in progress in the mid-2000s and for several years devoted about two hours every day to each project.[74] He is known to conduct exhaustive research on the historical settings and regional environments found in his fiction.[77] He continually edits his own writing, sometimes revising a book over the course of years or decades before deeming it fit for publication.[76] While his research and revision are meticulous, he does not outline his plots and instead views writing as a "subconscious process" which should be given space for spontaneous inspiration.[78]

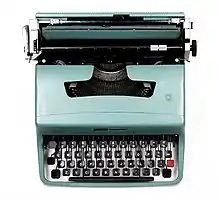

Since 1958, McCarthy has written all of his literary work and correspondence with a mechanical typewriter. He originally used a Royal but went looking for a more lightweight machine ahead of a trip to Europe in the early 1960s. He bought a portable Olivetti Lettera 32 for $50 at a Knoxville pawn shop and typed about five million words over the next five decades. He maintained it by simply "blowing out the dust with a service station hose". Book dealer Glenn Horowitz said the modest typewriter acquired "a sort of talismanic quality" through its connection to McCarthy's monumental fiction, "as if Mount Rushmore was carved with a Swiss Army knife".[74] His Olivetti was auctioned in December 2009 at Christie's, with the auction house estimating it would fetch between $15,000 and $20,000. It sold for $254,500, with proceeds donated to the Santa Fe Institute.[79] McCarthy replaced it with an identical model, bought for him by his friend John Miller for $11 plus $19.95 for shipping.[74]

Personal life and views

McCarthy is reportedly a teetotaler. According to Richard B. Woodward: "McCarthy doesn't drink anymore – he quit 16 years ago in El Paso, with one of his young girlfriends – and Suttree reads like a farewell to that life. 'The friends I do have are simply those who quit drinking,' he says. 'If there is an occupational hazard to writing, it's drinking.'"[80]

In the late 1990s, McCarthy moved to the Tesuque, New Mexico area, north of Santa Fe, with his third wife, Jennifer Winkley, and their son, John. McCarthy and Winkley divorced in 2006.[17]

In 2016, a hoax spread on Twitter claiming that McCarthy had died, with USA Today even repeating the information.[81] The Los Angeles Times responded to the hoax with the headline, "Cormac McCarthy isn't dead. He's too tough to die."[82]

Politics

Writer Benjamin Nugent has noted that McCarthy is seemingly apolitical, having not publicly revealed his political opinions.[83] While discussing the people of Santa Fe, New Mexico with Vanity Fair, McCarthy said "If you don't agree with them politically, you can't just agree to disagree—they think you're crazy."[17] In the 1980s, McCarthy and Edward Abbey considered covertly releasing wolves into southern Arizona to restore the decimated population.[84]

Science and literature

In one of his few interviews, McCarthy revealed that he only respects authors who "deal with issues of life and death", citing Henry James and Marcel Proust as examples of writers who do not rate with him. "I don't understand them ... To me, that's not literature. A lot of writers who are considered good I consider strange," he said.[22] Regarding his own literary constraints when writing novels, McCarthy said he is "not a fan of some of the Latin American writers, magical realism. You know, it's hard enough to get people to believe what you're telling them without making it impossible. It has to be vaguely plausible."[85] He has cited Moby-Dick (1851) as his favorite novel.[17]

McCarthy has an aversion to other writers, preferring the company of scientists. He has voiced his admiration for scientific advances: "What physicists did in the 20th century was one of the extraordinary flowerings ever in the human enterprise."[17] At MacArthur reunions, McCarthy has typically shunned his fellow writers to fraternize instead with scientists like physicist Murray Gell-Mann and whale biologist Roger Payne. Of all of his interests, McCarthy stated, "Writing is way, way down at the bottom of the list."[22]

Legacy

In 2003, literary critic Harold Bloom named McCarthy as one of the four major living American novelists, alongside Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon, and Philip Roth.[86] His 1994 book The Western Canon had listed Child of God, Suttree, and Blood Meridian among the works of contemporary literature he predicted would endure and become "canonical".[87] Bloom reserved his highest praise for Blood Meridian, which he called "the greatest single book since Faulkner's As I Lay Dying", and though he held less esteem for McCarthy's other novels he said that "to have written even one book so authentically strong and allusive, and capable of the perpetual reverberation that Blood Meridian possesses more than justifies him. ... He has attained genius with that book."[88]

A comprehensive archive of McCarthy's personal papers is preserved at the Wittliff Collections, Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas. The McCarthy papers consists of 98 boxes (46 linear feet).[89] The acquisition of the Cormac McCarthy Papers resulted from years of ongoing conversations between McCarthy and Southwestern Writers Collection founder, Bill Wittliff, who negotiated the proceedings.[90] The Southwestern Writers Collection/Wittliff Collections also holds The Wolmer Collection of Cormac McCarthy, which consists of letters between McCarthy and bibliographer J. Howard Woolmer,[91] and four other related collections.[91]

List of works

Notes

References

- Don Williams. "Cormac McCarthy Crosses the Great Divide". New Millennium Writings. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- Cowley, Jason (January 12, 2008). "A shot rang out ..." The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on October 17, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- National Book Foundation; retrieved March 28, 2012.

(With acceptance speech by McCarthy and essay by Harold Augenbraum from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.) - Fred Brown, "Childhood Home Made Cormac McCarthy Archived November 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine," Knoxville News Sentinel, January 29, 2009; retrieved July 14, 2017.

- Jurgensen, John (November 13, 2009). "Hollywood's Favorite Cowboy". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Cormac McCarthy: A Biography Archived April 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Cormac McCarthy Society official website; retrieved April 27, 2012.

- Jack Neely, "The House Where I Grew Up", Metro Pulse, February 3, 2009; accessed October 2, 2015.

- Woodward, Richard B. (April 19, 1992). "Cormac McCarthy's Venomous Fiction". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 3, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Jack Neely, Jim "J-Bone" Long, 1930-2012: One Visit With a Not-Quite Fictional Character, Metro Pulse, September 19, 2012; accessed October 2, 2015.

- Wesley Morgan, Rich Wallach (ed.), "James William Long Archived July 29, 2020, at the Wayback Machine," You Would Not Believe What Watches: Suttree and Cormac McCarthy's Knoxville (LSU Press, 1 May 2013), p. 59.

- Adams, Tim (December 19, 2009). "Cormac McCarthy: America's great poetic visionary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 11, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Giemza, Bryan (July 8, 2013). Irish Catholic Writers and the Invention of the American South. LSU Press. ISBN 9780807150924. Retrieved November 29, 2017 – via Google Books.

- Hall, Michael (July 1998). "Desperately Seeking Cormac". Texas Monthly. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- "Obituary: Lee McCarthy". The Bakersfield Californian. March 29, 2009. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- Brown, Paul F. (2018). Rufus: James Agee in Tennessee. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. pp. 251–52. ISBN 978-1621904243.

- Lewis, Kimberly (2004). "The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature: McCarthy, Cormac | Books |". New York: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- Woodward, Richard B. (August 2005). "Cormac Country". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on August 15, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "Still Another Disciple of William Faulkner". movies2.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- THE ORCHARD KEEPER by Cormac McCarthy | Kirkus Reviews. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- "New Cormac McCarthy Book, 'The Passenger,' Unveiled". August 15, 2015. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Arnold, Edwin (1999). Perspectives on Cormac McCarthy. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-105-9.

- Woodward, Richard (May 17, 1998). "Cormac McCarthy's Venomous Fiction". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 20, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- "Novelist reimagines Graniteville murder" Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Aiken Standard, September 10, 2010. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- McCarthy, Cormac. The Gardener's Son. The Ecco Press, September 1, 1996. Retrieved December 6, 2010. Front and back book flaps.

- "Primetime Emmy award database" Archived April 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- Charyn, Jerome (February 18, 1979). "Suttree". The New York Times. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- "Cormac McCarthy Papers". April 14, 2020. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- Broyard, Anatole (January 20, 1979). "Books of The Times". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Bloom, Harold (June 15, 2009). "Harold Bloom on Blood Meridian". A.V. Club. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- "What Is the Best Work of American Fiction of the Last 25 Years?". The New York Times. May 21, 2006. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- "Bloom on "Blood Meridian"". Archived from the original on March 24, 2006.

- Dalrymple, William. "Blood Meridian is the Great American Novel". Reader's Digest. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

McCarthy's descriptive powers make him the best prose stylist working today, and this book the Great American Novel.

- Lev Grossman and Richard Lacayo (October 16, 2005). "All Time 100 Novels – The Complete List". Time. Archived from the original on April 25, 2010. Retrieved June 3, 2008.

- Phillips, Dana (2014). "History and the Ugly Facts of Blood Meridian". In Lilley, James D. (ed.). Cormac McCarthy: New Directions. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 17–46.

- Schedeen, Jesse (April 2, 2020). "Binge It! The Allure of Cormac McCarthy's Beautifully Desolate Border Trilogy". IGN. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- The Stonemason. UNC-Chapel Hill Library catalog. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 1994. ISBN 9780880013598. Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- Battersby, Eileen (October 25, 1997). "The Stonemason by Cormac McCarthy". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- "Fiction" Archived April 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Past winners & finalists by category, Pulitzer.org; retrieved March 28, 2012.

- Frye, S. (2006). "Yeats' 'Sailing to Byzantium' and McCarthy's No Country for Old Men: Art and Artifice in the New Novel". The Cormac McCarthy Society Journal. 5.

- John Jurgensen (April 25, 2020). "Hollywood's Favorite Cowboy". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- Winfrey, Oprah. "Oprah's Exclusive Interview with Cormac McCarthy Video". Oprah Winfrey Show. Harpo Productions, Inc. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- - Roger Ebert Archived January 16, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- "The Guardian review of The Road". Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- "Empire Online". Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- Jones, Chris (May 29, 2006). "Brilliant, but hardly a play". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 14, 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Zinoman, Jason (October 31, 2006). "A Debate of Souls, Torn Between Faith and Unbelief". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Jones, Chris (May 29, 2006). "Brilliant, but hardly a play". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 14, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Van Gelder, Lawrence (March 29, 2007). "Arts, Briefly". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015.

- Conlon, Michael (June 5, 2007). "Writer Cormac McCarthy confides in Oprah Winfrey". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019.

- "Cormac McCarthy Sells First Spec Script". TheWrap. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- "Guardian review". Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- "Rolling Stone review". Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- "NY Times review". Archived from the original on April 16, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- Romeo, Rick (April 22, 2017). "Cormac McCarthy explains the unconscious". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- McCarthy, Cormac (April 20, 2017). "The Kekulé Problem: Where did language come from?". Nautilus. No. 47. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Jones, Josh (August 13, 2013). "Cormac McCarthy's Three Punctuation Rules, and How They All Go Back to James Joyce". Open Culture. Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- Lincoln, Kenneth (2009). Cormac McCarthy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 14. ISBN 978-0230619678.

- Crystal, David (2015). Making a Point: The Pernickity Story of English Punctuation. London: Profile Book. p. 92. ISBN 978-1781253502.

- Hage, Erik (2010). Cormac McCarthy: A Literary Companion. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. p. 156. ISBN 978-0786443109.

- Greenwood, Willard P. (2009). Reading Cormac McCarthy. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 4. ISBN 978-0313356643.

- Tetzeli, Rick (December 7, 2016). "A Short History Of The Most Important Economic Theory In Tech". Fast Company. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- Flood, Alison (February 21, 2012). "Cormac McCarthy's parallel career revealed – as a scientific copy editor!". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- Bell, Vereen M. (Spring 1983). "The Ambiguous Nihilism of Cormac McCarthy". The Southern Literary Journal. 15 (2): 31–41. JSTOR 20077701.

- "Harold Bloom on Blood Meridian". The A.V. Club. June 15, 2009. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Daugherty, Leo (1999). "Gravers False and True: Blood Meridian as Gnostic Tragedy". In Arnold, Edwin; Luce, Dianne (eds.). Perspectives on Cormac McCarthy. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. Project MUSE. ISBN 9781604736502. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Mundik, Petra (2009). ""Striking the Fire Out of the Rock": Gnostic Theology in Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian". South Central Review. 26 (3): 72–97. doi:10.1353/scr.0.0057. S2CID 144187406. Archived from the original on June 2, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Wielenberg, Erik J. (Fall 2010). "God, Morality, and Meaning in Cormac McCarthy's The Road" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 10, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Hwang, Jung-Suk (2018). "The Wild West, 9/11, and Mexicans in Cormac McCarthy's No Country for Old Men". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 60 (3): 346–371. doi:10.7560/TSLL60304. S2CID 165691304.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Cormac McCarthy: An American Philosophy | the Artifice". Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Herlihy-Mera, Jeffrey. Mojado Reverso; or, A Reverse Wetback: On John Grady Cole's Mexican Ancestry in All the Pretty Horses" Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Modern Fiction Studies, Fall 2015; retrieved October 15, 2015.

- Herlihy-Mera, Jeffrey. "Mojado Reverso; or, A Reverse Wetback: On John Grady Cole's Mexican Ancestry in All the Pretty Horses" Archived March 12, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Modern Fiction Studies, Fall 2015; retrieved March 25, 2016.

- Cohen, Patricia (November 30, 2009). "No Country for Old Typewriters: A Well-Used One Heads to Auction". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020.

- Jones, Josh (February 27, 2017). "Cormac McCarthy Explains Why He Worked Hard at Not Working: How 9-to-5 Jobs Limit Your Creative Potential". Open Culture. Archived from the original on October 4, 2019.

- Davis, Steve (September 23, 2010). "Unpacking Cormac McCarthy". The Texas Observer. Archived from the original on July 10, 2020.

- "News — Exhibition on McCarthy's Process". The Wittliff Collections at Texas State University. September 10, 2014. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020.

- Kushner, David (December 2007). "Cormac McCarthy's Apocalypse". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020 – via DavidKushner.com.

- Kennedy, Randy (December 4, 2009). "Cormac McCarthy's Typewriter Brings $254,500 at Auction". ArtsBeat. The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2009. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- "The New York Times: Book Review Search Article". The New York Times. May 17, 1998. Archived from the original on July 16, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- "Cormac McCarthy is not dead". June 28, 2016. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Schaub, Michael (June 28, 2016). "Cormac McCarthy isn't dead. He's too tough to die". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "Why Don't Republicans Write Fiction?". March 6, 2007. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Woodward, Richard B. (April 19, 1992). "Cormac McCarthy's Venomous Fiction". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 3, 2018. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "A conversation between author Cormac McCarthy and the Coen Brothers, about the new movie No Country for Old Men". Time.com. October 18, 2007. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017.

- Bloom, Harold (September 24, 2003). "Dumbing down American readers". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020 – via Boston.com.

- Bloom, Harold (1994). "Appendix D: The Chaotic Age: A Canonical Prophecy". The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. Orlando, Florida: Harcourt Brace & Company. pp. 548–567. ISBN 0-15-195747-9 – via the Internet Archive (registration required).

- Pierce, Leonard (June 15, 2009). "Harold Bloom on Blood Meridian". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020.

- "Cormac McCarthy Papers at The Wittliff Collections, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX". Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- "Texas State acquires McCarthy archives". The Hollywood Reporter. Associated Press. January 15, 2008. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- "Woolmer Collection of Cormac McCarthy : The Wittliff Collections : Texas State University". Thewittliffcollections.txstate.edu. September 21, 2016. Archived from the original on December 19, 2017. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

Further reading

- Frye, Steven (2009). Understanding Cormac McCarthy. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1570038396.

- Frye, Steven, ed. (2013). The Cambridge Companion to Cormac McCarthy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107644809.

- Luce, Dianne C. (2001). "Cormac McCarthy: A Bibliography". The Cormac McCarthy Journal. 1 (1): 72–84. JSTOR 4290933. (updated version published 26 October 2011)

- "Connecting Science and Art". Science Friday. April 8, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Cormac McCarthy |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cormac McCarthy. |

- The Cormac McCarthy Society

- Southwestern Writers Collection at the Wittliff Collections, Texas State University – Cormac McCarthy Papers

- Works by or about Cormac McCarthy in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Cormac McCarthy at IMDb

- Western American Literature Journal: Cormac McCarthy