Edna Ferber

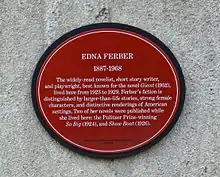

Edna Ferber (August 15, 1885 – April 16, 1968) was an American novelist, short story writer and playwright. Her novels include the Pulitzer Prize-winning So Big (1924), Show Boat (1926; made into the celebrated 1927 musical), Cimarron (1930; adapted into the 1931 film which won the Academy Award for Best Picture), Giant (1952; made into the 1956 film of the same name) and Ice Palace (1958), which also received a film adaptation in 1960.

Edna Ferber | |

|---|---|

Edna Ferber in 1928 | |

| Born | August 15, 1885 Kalamazoo, Michigan, United States |

| Died | April 16, 1968 (age 82) New York City, New York, United States |

| Occupation | Novelist, playwright |

| Nationality | United States |

| Genre | Drama, romance |

Life and career

Early years

Ferber was born August 15, 1885, in Kalamazoo, Michigan, to a Hungarian-born Jewish storekeeper, Jacob Charles Ferber, and his Milwaukee, Wisconsin-born wife, Julia (Neumann) Ferber, who was of German Jewish descent.[1] She moved often due to her father's business failures, likely caused by his early blindness.[2] After living in Chicago, Illinois, she moved to Ottumwa, Iowa with her parents and older sister, Fannie, where they resided for 7 years (age 5 to 12 for Ferber). In Ottumwa, Ferber and her family faced brutal anti-Semitism, including adult males verbally abusing, mocking and spitting on her every day when she brought lunch to her father, often mocking her in a Yiddish accent.[3][4] At the age of 12, Ferber and her family moved to Appleton, Wisconsin, where she graduated from high school and briefly attended Lawrence University.

Career

Initially going to study acting, Ferber abandoned these plans to help support her family at age 17. Forbidden to study elocution and on the spur of the moment, Ferber ended her higher education and dropped out of Lawrence, subsequently being hired at the Appleton Daily Crescent and eventually the Milwaukee Journal.[5] She covered the 1920 Republican National Convention and 1920 Democratic National Convention for the United Press Association[6] during her period as a reporter.

When recovering from anemia,[7] Ferber's first short stories were compiled and published along with her first novel, Dawn O'Hara, The Girl Who Laughed, was published in 1911.

In 1925, she won the Pulitzer Prize for her book, So Big. Ferber initially believed her draft of what would become So Big lacked a plot, glorified failure, and had a subtle theme that could easily be overlooked. When she sent the book to her usual publisher, Doubleday, she was surprised to learn that he strongly enjoyed the novel. This was reflected by the several hundreds of thousands of copies of the novel sold to the public.[8] Following the award, the novel was made into a silent film starring Colleen Moore that same year. An early talkie movie remake followed in 1932, starring Barbara Stanwyck and George Brent, with Bette Davis in a supporting role. A 1953 remake of So Big starring Jane Wyman is the most popular version to modern audiences.

Riding off the popularity of So Big, Ferber's next novel, Show Boat, was just as successful and shortly after its release, the idea of turning it into a musical was brought up. When composer Jerome Kern proposed this, Ferber was shocked, thinking it would be transformed into a typical light entertainment of the 1920s. It was not until Kern explained that he and Oscar Hammerstein II wanted to create a different type of musical that Ferber granted him the rights and it premiered on Broadway in 1927, and has been revived 8 times following its first run.

Death

Ferber died at her home in New York City, of stomach cancer,[9] at the age of 82. Ferber left her estate to her remaining female relatives, but gave the American government permission to spread her literary work to encourage and inspire future female authors.[3]

Personal life

Ferber never married, had no children, and is not known to have engaged in a romance or sexual relationship.[10] In her early novel Dawn O'Hara, the title character's aunt even remarks, "Being an old maid was a great deal like death by drowning – a really delightful sensation when you ceased struggling." Ferber did take a maternal interest in the career of her niece Janet Fox, an actress who performed in the original Broadway casts of Ferber's plays Dinner at Eight (1932) and Stage Door (1936).

Ferber was known for being outspoken and having a quick wit. On one occasion, she led other Jewish guests in leaving a house party after learning the host was anti-Semitic.[3] Once, after a man joked about how her suit made her resemble a man, she replied, "So does yours."[4]

The quality of her work was so high that many literary critics believed a man to have written her narratives under a pseudonym of a woman.[3]

Importance of Jewish identity

Starting in 1922, Ferber began to visit Europe once or twice annually for thirteen or fourteen years.[11] During this time and unlike most Americans, she became troubled by the rise of the Nazi Party and its spreading of the antisemitic prejudice she had faced in her childhood. She commented on this saying, "It was a fearful thing to see a continent - a civilization - crumbling before one's eyes. It was a rapid and seemingly inevitable process to which no one paid any particular attention."[12] Her fears greatly influenced her work, which often featured themes of racial and cultural discrimination. Her 1938 autobiography, A Peculiar Treasure, originally included a spiteful dedication to Adolf Hitler which stated:

"To Adolf Hitler, who has made me a better Jew and a more understanding human being, as he has of millions of other Jews, this book is dedicated in loathing and contempt."[13]

While this was changed by the time of the book's publication, it still alluded to the Nazi threat.[11] She frequently mentions Jewish success in her book, alluding to and wanting to show not just that Jewish success, but Jews being able to utilize that and prevail.[11]

Algonquin Round Table

Ferber was a member of the Algonquin Round Table, a group of wits who met for lunch every day at the Algonquin Hotel in New York. Ferber and another member of the Round Table, Alexander Woollcott, were long-time enemies, their antipathy lasting until Woollcott's death in 1943, although Howard Teichmann states in his biography of Woollcott that their feud was due to a misunderstanding. According to Teichmann, Ferber once described Woollcott as "a New Jersey Nero who has mistaken his pinafore for a toga".

Ferber collaborated with Round Table member George S. Kaufman on several plays presented on Broadway: Minick (1924), The Royal Family (1927), Dinner At Eight (1932), The Land Is Bright (1941), Stage Door (1936), and Bravo! (1948).[14]

Political views

In a poll carried out by the Saturday Review of Literature, asking American writers which presidential candidate they supported in the 1940 election, Ferber was among the writers who endorsed Franklin D. Roosevelt.[15]

Characteristics of works

Ferber's novels generally featured strong female protagonists, along with a rich and diverse collection of supporting characters. She usually highlighted at least one strong secondary character who faced discrimination, ethnic or otherwise.

Ferber's works often concerned small subsets of American culture, and took place in locations she was not intimately familiar with, like Texas or Alaska. By using places she hadn't visited in her novels and describing them only through her research, she helped to highlight the diversity of American culture to those who did not have the opportunity to experience it.

Legacy

Art, entertainment, and media

- Ferber was portrayed by the actress Lili Taylor in the film Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle (1994).[16]

- In 2008, The Library of America selected Ferber's article "Miss Ferber Views 'Vultures' at Trial" for inclusion in its two-century retrospective of American True Crime.

- On July 29, 2002, in her hometown of Appleton, Wisconsin, the U.S. Postal Service issued an 83¢ Distinguished Americans series postage stamp honoring her. Artist Mark Summers, well known for his scratchboard technique, created this portrait for the stamp referencing a black-and-white photograph of Ferber taken in 1927.[17]

- A fictionalized version of Edna Ferber appears briefly as a character in Philipp Meyer's novel The Son (2013).

- An additional fictionalized version of Edna Ferber, with her as the protagonist, appears in a series of mystery novels by Ed Ifkovic and published by Poisoned Pen Press, including Downtown Strut: An Edna Ferber mystery, written in 2013 .

- In 2013, Ferber was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.[18]

List of works

Ferber wrote thirteen novels, two autobiographies, numerous short stories, and nine plays, many which were written in collaborations with other playwrights.[21]

Novels

- Dawn O'Hara, The Girl Who Laughed (1911)

- Fanny Herself (1917)

- The Girls (1921)

- Gigolo (1922)

- So Big (1924) (won Pulitzer Prize)

- Show Boat (1926, Grosset & Dunlap)

- Cimarron (1930)

- American Beauty (1931)

- Come and Get It (1935)

- Saratoga Trunk (1941)

- Great Son (1945)

- Giant (1952)

- Ice Palace (1958)

Novellas and Short Story Collections

- Buttered Side Down (1912)

- Roast Beef, Medium (1913) Emma McChesney stories

- Personality Plus (1914) Emma McChesney stories

- Emma Mc Chesney and Co. (1915) Emma McChesney stories

- Cheerful – By Request (1918)

- Half Portions (1919)

- Mother Knows Best (1927)

- They Brought Their Women (1933)

- Nobody's in Town: Two Short Novels (1938) Contains Nobody's in Town and Trees Die at the Top

- One Basket: Thirty-One Short Stories (1947) Includes "No Room at the Inn: A Story of Christmas in the World Today"

Autobiographies

- A Peculiar Treasure (1939)

- A Kind of Magic (1963)

Plays

- Our Mrs. McChesney (1915) (play, with George V. Hobart)

- $1200 a Year: A Comedy in Three Acts (1920) (play, with Newman Levy)

- Minick: A Play (1924) (play, with G. S. Kaufman)

- Stage Door (1926) (play, with G.S. Kaufman)

- The Royal Family (1927) (play, with G. S. Kaufman)

- Dinner at Eight (1932) (play, with G. S. Kaufman)

- The Land Is Bright (1941) (play, with G. S. Kaufman)

- Bravo (1949) (play, with G. S. Kaufman)

Screenplays

- Saratoga Trunk (1945) (film, with Casey Robinson)

Musical adaptations

- Show Boat (1927) – music by Jerome Kern, lyrics and book by Oscar Hammerstein II, produced by Florenz Ziegfeld

- Saratoga (1959) – music by Harold Arlen, lyrics by Johnny Mercer, dramatized by Morton DaCosta

- Giant (2009) – music and lyrics by Michael John LaChiusa, book by Sybille Pearson

References

- Footnotes

- "Edna Ferber | Jewish Women's Archive". jwa.org. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- "Edna Ferber". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- "Edna Ferber". www.nndb.com. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- "Edna Ferber | Jewish Women's Archive". jwa.org. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- "Edna Ferber". americanliterature.com. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- "So Big". Tablet Magazine. May 2, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- Smyth, J. E. (2010). Edna Ferber's Hollywood: American fictions of gender, race, and history (1st ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292719842. OCLC 318870278.

- R. Baird Shuman (2002). Great American Writers: Twentieth Century. Marshall Cavendish. p. 503. ISBN 978-0-7614-7240-7.

- Ferber has been rumored to be a lesbian in several undocumented sources. Professor John Unsworth makes an unsupported claim in John Sutherland (2007) Bestsellers: A Very Short Introduction Oxford University Press: 53. Haggerty and Zimmerman imply she was gay because of her visits to Provincetown in the early 20th century (Haggerty and Zimmerman (2000), Lesbian Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia, Taylor and Francis, p. 610). Porter (Porter, Darwin (2004) Katherine the Great, Blood Moon Productions, Ltd, p. 204) comments in passing that Ferber was a lesbian, but offers no support. Burrough (Burrough, Brian (2010) The Big Rich: The Rise and Fall of the Greatest Texas Oil Fortunes, Penguin) also remarks in passing that Ferber was gay, citing the biography written by Julie Goldsmith Gilbert (Ferber's great niece, see bibliography). Gilbert, however, makes no mention of lesbian relationships.

- Shapiro, Ann R. (2002). "Edna Ferber, Jewish American Feminist". Shofar. 20 (2): 52–60.

- Ferber, Edna (1938). A Peculiar Treasure. Doubleday. p. 267.

- "Edna Ferber | Jewish Women's Archive". jwa.org. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- "About the Playwright: The Royal Family – The Kaufman-Ferber Partnership". Utah Shakespeare Festival. The Professional Theater at Southern Utah University. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- "Among those who have stated they will vote for President Roosevelt are Edna Ferber..." "Editorial: Presidential Poll", Saturday Review of Literature. November 2, 1940 (p.8).

- "Mrs Parker and the Vicious Circle". Imdb.com. imdb.com. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- The Postal Store (2008). "Distinguished Americans Series: Edna Ferber". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- "Edna Ferber". Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- Edna Ferber Elementary School homepage.

- "Ferber School Issue Raised Again". The Post-Crescent. October 2, 1973. p. 9. Retrieved December 18, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Edna Ferber | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- Bibliography

- Ferber, Edna (1960). A Peculiar Treasure. New York: Doubleday.

- Gilbert, Julie Goldsmith (2000). Edna Ferber and Her Circle, A Biography. New York: Hal Leonard Corporation.

- Archives

- Doubleday correspondence with Edna Ferber, 1932-1954. Chapin Library, Williams College.

- Edna Ferber Collection, 1921-2002. Lawrence University Archives, Lawrence University.

- Edna Ferber Papers. Wisconsin Historical Society.

- Edna Ferber Collection. Appleton Public Library.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Edna Ferber |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edna Ferber. |

Online editions

- Works by Edna Ferber at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Edna Ferber at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Edna Ferber at Internet Archive

- Works by Edna Ferber at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)