Crows and Sparrows

Crows and Sparrows (simplified Chinese: 乌鸦与麻雀; traditional Chinese: 烏鴉與麻雀; pinyin: Wūyā yŭ Máquè) is a 1949 Chinese film made by the left-leaning Kunlun Studios on the eve of the Communist victory, directed by Zheng Junli and scripted by Chen Baichen.[1] Notable for its extremely critical view of corrupt Nationalist bureaucrats, the film was made as Chiang Kai-shek's Nanjing-based government was on the verge of collapse, and was not actually released until after the Chinese Civil War had ended.[2]

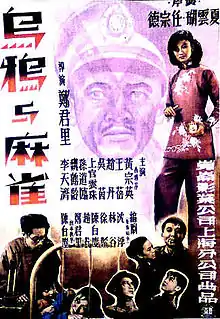

| Crows and Sparrows | |

|---|---|

Chinese poster for Crows and Sparrows (1949) | |

| Traditional | 烏鴉與麻雀 |

| Simplified | 乌鸦与麻雀 |

| Mandarin | Wūyā yŭ máquè |

| Directed by | Zheng Junli |

| Produced by | Xia Yunhu Ren Zongde |

| Starring | Zhao Dan Sun Daolin Li Tianji Huang Zongying Shangguan Yunzhu Wu Yin |

| Music by | Wang Yunjie |

Production company | Kunlun Film Company |

Release date |

|

Running time | 111 minutes |

| Country | China |

| Language | Mandarin |

The film takes place in Shanghai, and it revolves around a group of tenants struggling to prevent themselves from being thrown out onto the street due to a corrupt party official’s attempts to sell their apartment building.

The film was the winner of the 1957 Huabiao Film Awards for the “Outstanding Film” category, and starred Zhao Dan, Sun Daolin, Wu Yin and Shangguan Yunzhu in leading roles.

Plot

In the winter of 1948, the Kuomintang of China (KMT) is losing in the Huai Hai Campaign with Communist Party of China (CPC) during the Civil War. Kuomintang government officials start to persecute the people more severely to keep their the original luxurious life. At a Shanghai shikumen house, Mr. Hou, a former Japanese collaborator (Section chief of the Kuomintang defense department) and now an opportunist KMT official, is planning to sell the house which he seized from the owner Kong Yuwen, and then about to fly to Taiwan.[3] His mistress, Yu Xiaoying or so-called Mrs. Hou, gives an ultimatum to the rest of the tenants to move out.

The house is tenanted by three families: Mr. Kong, a proofreader in a newspaper agency, whose son joined the New Fourth Army; Mr. and Mrs. Xiao, foreign goods vendors with their three kids, Da Mao, Er Mao and Little Mao; and a schoolteacher, Mr. Hua, his wife and their daughter Wei Wei. When Mr. Xiao proposes they should band together, others disagree and want to find other ways out. So Mr. Kong and Mr. Hua try to find a place to stay at their workplaces respectively, while Mr. and Mrs. Xiao hope to invest in black market gold in order to buy the house from Mr. Hou with three gold bars.

However, things don't go as they expected. The employer is unwilling to provide Mr. Kong with accommodation. Mr. Hua was arrested by KMT agents since he signed a protest letter over the school administration permitting for police to unjustly arrest its employees. Mr. and Mrs. Xiao find their scheme of making rich go to nought after gold price rises sharply due to the government’s manipulation. What's worse, they're beaten by the crowd who are also waiting to trade gold yuan notes for gold at central bank. Meanwhile, desperate as she is, Mrs. Hua resorts to ask Mr. Hou for rescuing her husband out of jail, but Hou only wants to make her as his mistress. Infuriated, Mrs. Hua rejects him and rushes home, while her daughter falls desperately ill. With generous help from Mr. Kong and Xiao Amei— Mrs. Hou’s kind-hearted maid— Wei Wei, Mr. and Mrs. Xiao fully recover from their illness and injuries.[2]

The tenants finally decide not to move out in a showdown with Mr. Hou. Soon, Hou receives a phone call, telling him that the defeated KMT is about to abandon its capital, Nanjing and retreat to Taiwan. In the early morning, he and his mistress sneak out of the house and prepare to flee to Taiwan. The KMT agents release Mr. Hua while his fellow teachers are executed. As the remaining KMT members all run off from Mainland China, the tenants celebrate Chinese New Year in 1949, promising to improve themselves in the face of the coming new society.

Cast

- Wei Heling as Kong Youwen (nicknamed Confucius)

- Zhao Dan as Mr. Xiao (nicknamed Little Broadcast)

- Wu Yin as Mrs. Xiao

- Sun Daolin as Hua Jiezhi

- Shangguan Yunzhu as Mrs. Hua

- Li Tianji as Hou Yibo

- Huang Zongying as Yu Xiaoying (or Mrs. Hou)

- Wang Bei as Ah Mei

- Wang Lulu as Wei Wei

- Xu Weijie as Da Mao

- Qiu Huan as Er Mao

- Ge Meiqiang as Little Mao

Introduction of main characters

- Kong Youwen (nicknamed Confucius)

An experienced proof-reader in the newspaper office, who has no social power, as a member of the social underclass. As his son joined the New Fourth Army, he then was threatened by Hou Yibo, who forcibly occupied his house. - Mr. Xiao (nicknamed Little Broadcast)

A street vendor who volunteers to fight against Hou Yibo but failed. He then mortgaged all of his valuable jewelry and western medicines to Hou Yibo so that he could invest in the gold speculation and make money out of it to buy himself a house. However, Boss Xiao was wounded by gangsters and all of their collaterals from the mortgage were taken by Hou Yibo. - Hua Jiezhi

A high school teacher with a high opinion of himself but refused to lead a rebellion. He planned to move to the school but was threatened by the Headmaster- a KMT spy, with ransom equivalent to one of the school dorms. - Hou Yibo

Chief of KMT defense department, took Kong Youwen’s house by force. He then let his concubine Yu Xiaoying live on the second floor. When he realized that the situation was getting worse, he planned to sell the house and make some money out of it. Later when the KMT collapsed, he panicked and escaped with Xiaoying in a hurry without selling other properties he took by force before. - Yu Xiaoying (or Mrs. Hou)

A concubine of Hou Yibo. Together with Hou Yibo, they massively defrauded and plundered people. She then had to escape with Hou Yibo when the KMT regime collapsed.

Theme & Title

In 1948, China’s political situation was unstable and the Communist Party of China (CCP) was carrying out three major battles against Kuomintang. The inspiration behind this film’s theme originated from a moment where several actors from Kunlun Film Company were having a meal, and talking about the difficulties of the concurrent situation- the conflict between the KMT and the CCP, and felt that there would be a great political change right away, and thus they decided to shoot a feature film to record the doomsday of the Kuomintang in the hope of a new future with a renewed Chinese society. It is an allegorical work which uses metaphor and symbolism from the title alone throughout the whole film.

The "house" serves as a nation usurped by dictators but eventually returned to its original owners, who promise to construct a new future. The two-storey house epitomises and literalises the social hierarchy of the crows and the sparrow, Hou and his mistress lord it over the tenants and live upstairs, where Kong used to live as the original owner. The tenants divide up the rooms below according to their social positions and professions.[4]

The “Crows” represent the corrupt officers and the oppressive power of the Kuomintang, while the “Sparrows” symbolize the commoners, namely the oppressed citizens of China suffering under the KMT’s iron grip. The director used low angle shots to portray the Crows living upstairs as powerful dominators looming over the commoners, whilst also using high angle shots to convey the weakness and powerlessness of the Sparrows over their KMT overlords. But eventually, the Crows were overthrown, and the apartment eventually returned to the hands of the Sparrows; the common folk of China. The film underlines the co-implicating relationship between the oppressors and the oppressed by visualizing their simultaneous distance and proximity with respect to the usage of mise-en-scène, and literal physical distance. Such proximity produces a kind of porosity that allows the Sparrows to monitor the Crows––thus, facilitating their subversion of the existing social hierarchy.[5]

Reception

“Initial reviews of the film, which appeared in mid-April 1951, were encouraging. Popular Cinema (Dazhong Dianying 大众电影), the leading film fan magazine, ran a nicely illustrated and friendly report that contained no hint of problems. Xin Min Bao (新民报), a Shanghai news daily, published three reviews, all praising it”.[6]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Huabiao Awards (1957) | Outstanding Film[7] | Zheng Junli | Won |

| Huabiao Awards (1957) | Best Actress[8] | Wu Yin | Won |

Background

Historical background

In 1945, after the surrender of Japan, the Chinese Civil War between the KMT (Kuomintang) and CPC (Communist Party of China) was launched. This film was produced nearly at the end of the Chinese Civil War and was shown on November 1, 1949 in China, which just in one month after Mao Zedong proclaimed the People’s Republic of China from atop Tiananmen. The film gives viewers a window into Chinese society during the Chinese Civil War period, and a deeper insight on how people suffered as a result of the KMT’s oppressive rule and martial governance. Between the years 1935 to 1949, China experienced a state of hyperinflation in which prices rose by more than a thousandfold, with even one occasion where the nation saw a dramatic inflation in currency in a single day in this period. During that time, the Nationalists also were poorly mistreating Chinese citizens in Shanghai, and the film depicts how they went about strong-arming the local residents, and what happened after they knew that they were on the losing side of the war. In the early months in 1948, people doubted whether the CCP were truly able to win the Civil War. In 1949, the Kuomintang moved the gold and money they stored in the Bank of Shanghai to Taiwan, perhaps in preparation for their great exodus out of the mainland. In the same year, nearing the end of the Chinese Civil War, people predicted that the Communist Party of China had better odds of winning the war. With this in mind, the film was produced describing a story set in Shanghai in 1948––particularly the Nationalist-controlled regions of the city.

Social Context

In 1949, nearing the end of the Chinese Civil War, people predict that the Communist Party of China has a bigger chance to win this war. The film is produced during that time, and it described a story that happened in Shanghai in 1948, which is the area under the control of the Nationalist Government (KMT). In the early months in 1948, people would not know whether the CPC are able to win the Civil War. During that time, the nationalists are really tough on their people, and the film shows a story about how does a nationalist squeeze the people who live in the area that under his control and what happened after he knows that KMT are going to lose the war. Under the governance of KMT, China experienced a hyperinflation in which prices rose by more than a thousandfold between 1935 and 1949. In 1949, KMT moves gold and money they stored in the bank of shanghai to Taiwan. The film gives us an idea of a society during the Civil War and how people suffering from KMT's political power. Crows and Sparrows displays critical realism that is similar to prewar social realism.[9]

Political Views

Under the instruction of Zhou Enlai, Kunlun Film company was established in 1947. The leaders of the company were all supporters and members of the Communist Party of China (CPC). From beginning to end, director Zheng Junli loved the Communist Party and never questioned the legitimacy of his tormentors. He did everything the Party wanted him to do. Although Zheng Junli's 'leftist' films received support from the Communist Party, he would later be persecuted by the Red Guard during the Cultural Revolution. He died in prison in 1969 at the age of 58 [6] Similarly, the screenwriter Chen Baichen was a member of CPC since 1932. He wrote many scripts to support CPC during the civil war, but he was treated as a traitor based on his scripts, and imprisoned for many years.

Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou

In 1956, the Ministry of Culture of New China awarded a second prize to Crows and Sparrows. Premier Zhou Enlai was quite dissatisfied with the results: "These people risked their lives and shot such a good movie. How are they awarded the second prize?" This was passed to Mao Zedong, who had also watched the film and agreed with Zhou’s opinion. Then, the Ministry of Culture re-awarded Crows and Sparrows with the first prize. In the years when Premier Zhou suffering from cancer, he liked to rewatch old films including Crows and Sparrows.[10]

Production

“Progressive” Films under Kuomintang Censorship

Crows and Sparrows was made near the end of the Civil War, when “the outcome of the war was obvious to all” (Pickowicz, 1051). During this period, as Shanghai was still in control of the Nationalist Party, films and other cultural productions had to go through heavy censorship, often referred to as the “white terror”. Therefore, Chen Baichen (陈白尘), the screenwriter, prepared two versions of the screenplay, and managed to use the self-censored version to pass the censor. However, during the production, the hidden version was discovered by the censorship department and was compelled to stop as it “disturbed the social security and damaged government prestige” (“扰乱社会治安,破坏政府威信”). The production had to go underground until Shanghai’s liberation on May 27, 1949 which lead to the production being able to finish shooting during the daytime.[11] The films released by the central government were intended to glorify the KMT's corrupt actions, but the true voices of the people is the criticism produced by these private film studios.[12] Following the change in governance, the director, Zheng Junli, sped up the production of the film, Crows and Sparrows, which depicted the grievances of Chinese citizens under corrupt Nationalist bureaucrats and their policies, and was well-received upon its release.[13]

Inspiration

The idea of filming Crows and Sparrows originated during dinner between Chen Baichen, Shen Fu, Zheng Junli, Chen Yuting and Zhao Dan of Shanghai Kunlun Film Co., Ltd, and the script was completed overnight. In 1948, China’s political situation was unstable and the Communist Party and the KMT were fighting for the three major battles. During dinner, they discussed the unstable social situation and foresaw that the situation would change greatly so they were preparing to shoot a feature film that records the doomsday of Kuomintang’s regime and expresses the hope of the filmmakers’ hope for the new world. They also found several scriptwriters to talk over the night. soon discussed the outline of the script, named it Crows and Sparrows, and let Chen Baichen write the script. They also agreed to let Zheng Junli be the director, as he once co-directed with Spring River Flows East with Cai Chusheng.

Camera Movement

Actual Events

The screenwriter Chen Baichen tried to reveal problems by filming the actual events happened in Shanghai. In October 1948, inflation became more intense in Shanghai, and citizens had to purchase gold from the KMT government. Chen Baichen combined the event with his script, and filmed the scene of little Broadcast purchasing gold bars.[17]

Sets and Locations

Crows and Sparrows was filmed on location for the scene where Mrs. Hua tries to save Mr. Hua. The education building in the film was the real education department building of Shanghai (today’s Shanghai Central Plaza 中环广场).

External links

- Crows and Sparrows with English subtitles on YouTube

- Crows and Sparrows: full film and two video lectures, Chinesefilmclassics.org

- Complete English translation of Crows and Sparrows, and subtitled copy of film: https://u.osu.edu/mclc/online-series/crows-and-sparrows/

- Crows and Sparrows from the Chinese Movie Database

- Crows and Sparrows at IMDb

- Description and discussion questions from Ohio State University

- Crows and Sparrows Analysis on YouTube

References

- "Crows and Sparrows". China Institute. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- Bastian. "Crows and Sparrows - Festival des Cinémas d'Asie de Vesoul". www.cinemas-asie.com (in French). Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- michaelgloversmith. "Crows and Sparrows". White City Cinema. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- Wang, Yiman. (2008). Crows and Sparrows: Allegory on a Historical Threshold. 85-87

- Wang, Yiman. (2008). Crows and Sparrows: Allegory on a Historical Threshold.

- Pickowicz, P. (2006). Zheng Junli, Complicity and the Cultural History of Socialist China, 1949–1976. The China Quarterly, 188, 1048-1069.

- "Huabiao Film Awards (1957)". IMDb. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- "吴茵,是艺术家更是我的好妈妈". archive.is. 2013-10-20. Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- Yingjin, Zhang (2003). "Industry and Ideology: A Centennial review of Chinese Cinema". World Literature Today. 77 (3/4): 8–13. doi:10.2307/40158167. JSTOR 40158167.

- "Crows and Sparrows". www.news.ifeng.com.

- "Crows and Sparrows (Wuya yu Maque) | BAMPFA". bampfa.org. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ""Industry and Ideology: A Centennial review of Chinese Cinema". World Literature Today". Retrieved 2020-06-14.

- Pickowicz, Paul G. (2006). "Zheng Junli, Complicity and the Cultural History of Socialist China, 1949-1976". The China Quarterly. 188 (188): 1048–1069. doi:10.1017/S0305741006000543. JSTOR 20192704.

- Christopher Rea. "Crows and Sparrows (1949)". Retrieved 2020-06-14.

- JL Admin (2020-02-20). "Crows & Sparrows (1949 Movie): Summary & Analysis". Retrieved 2020-06-14.

- Christopher Rea. "Crows and Sparrows (1949)". Retrieved 2020-06-14.

- 陈虹. "我家的故事:陈白尘女儿的讲述". Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- Yingjin, Zhang (2003). "Industry and Ideology: A Centennial review of Chinese Cinema". World Literature Today. 77 (3/4): 8–13. doi:10.2307/40158167. JSTOR 40158167.