Cinema of China

The cinema of mainland China is one of three distinct historical threads of Chinese-language cinema together with the cinema of Hong Kong and the cinema of Taiwan.

| Cinema of China | |

|---|---|

A frame from the 1941 film Princess Iron Fan, Asia's first feature-length animated film[1] | |

| No. of screens | 41,179 (2016)[2] |

| • Per capita | 2.98 per 100,000 (2016) |

| Main distributors | China Film (32.8%) Huaxia (22.89%) Enlight (7.75%)[3] |

| Produced feature films (2016)[2] | |

| Fictional | 772 |

| Animated | 49 |

| Documentary | 32 |

| Number of admissions (2016)[4] | |

| Total | 1,370,000,000 |

| • Per capita | 1[4] |

| Gross box office (2016)[2] | |

| Total | CN¥45.71 billion (US$6.58 billion) |

| National films | 58.33% |

Cinema was introduced in China in 1896 and the first Chinese film, Dingjun Mountain, was made in 1905. In the early decades the film industry was centered on Shanghai. The first sound film, Sing-Song Girl Red Peony, using the sound-on-disc technology, was made in 1931.[5] The 1930s, considered the first "Golden Period" of Chinese cinema, saw the advent of the Leftist cinematic movement. The dispute between Nationalists and Communists was reflected in the films produced. After the Japanese invasion of China and the occupation of Shanghai, the industry in the city was severely curtailed, with filmmakers moving to Hong Kong, Chongqing and other places. A "Solitary Island" period began in Shanghai, where the filmmakers who remained worked in the foreign concessions. Princess Iron Fan (1941), the first Chinese animated feature film, was released at the end of this period. It influenced wartime Japanese animation and later Osamu Tezuka.[6] After being completely engulfed by the occupation in 1941, and until the end of the war in 1945, the film industry in the city was under Japanese control.

After the end of the war, a second golden age took place, with production in Shanghai resuming. Spring in a Small Town (1948) was named the best Chinese-language film at the 24th Hong Kong Film Awards. After the communist revolution in 1949, domestic films that were already released and a selection of foreign films were banned in 1951, marking a tirade of film censorship in China.[7] Despite this, movie attendance increased sharply. During the Cultural Revolution, the film industry was severely restricted, coming almost to a standstill from 1967 to 1972. The industry flourished following the end of the Cultural Revolution, including the "scar dramas" of the 1980s, such as Evening Rain (1980), Legend of Tianyun Mountain (1980) and Hibiscus Town (1986), depicting the emotional traumas left by the period. Starting in the mid to late 1980s, with films such as One and Eight (1983) and Yellow Earth (1984), the rise of the Fifth Generation brought increased popularity to Chinese cinema abroad, especially among Western arthouse audiences. Films like Red Sorghum (1987), The Story of Qiu Ju (1992) and Farewell My Concubine (1993) won major international awards. The movement partially ended after the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. The post-1990 period saw the rise of the Sixth Generation and post-Sixth Generation, both mostly making films outside the main Chinese film system which played mostly on the international film festival circuit.

Following the international commercial success of films such as Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Hero (2002), the number of co-productions in Chinese-language cinema has increased and there has been a movement of Chinese-language cinema into a domain of large scale international influence. After The Dream Factory (1997) demonstrated the viability of the commercial model, and with the growth of the Chinese box office in the new millennium, Chinese films have broken box office records and, as of January 2017, 5 of the top 10 highest-grossing films in China are domestic productions. Lost in Thailand (2012) was the first Chinese film to reach CN¥1 billion at the Chinese box office. Monster Hunt (2015) was the first to reach CN¥2 billion . The Mermaid (2016) was the first to CN¥3 billion . Wolf Warrior 2 (2017) beat them out to become the highest-grossing film in China.

China is the home of the largest movie & drama production complex and film studios in the world, the Oriental Movie Metropolis[8][9] and Hengdian World Studios, and in 2010 it had the third largest film industry by number of feature films produced annually. In 2012 the country became the second-largest market in the world by box office receipts. In 2016, the gross box office in China was CN¥45.71 billion (US$6.58 billion ). The country has the largest number of screens in the world since 2016,[10] and is expected to become the largest theatrical market by 2019.[11] China has also become a major hub of business for Hollywood studios.[12][13]

In November 2016, China passed a film law banning content deemed harmful to the “dignity, honor and interests” of the People's Republic and encouraging the promotion of “socialist core values", approved by the National People's Congress Standing Committee.[14] Due to industry regulations, films are typically allowed to stay in theaters for one month. However, studios may apply to regulators to have the limit extended.[15]

Beginnings

Motion pictures were introduced to China in 1896. China was one of the earliest countries to be exposed to the medium of film, due to Louis Lumière sending his cameraman to Shanghai a year after inventing cinematography.[5] The first recorded screening of a motion picture in China took place in Shanghai on August 11, 1896, as an "act" on a variety bill.[16] The first Chinese film, a recording of the Peking opera, Dingjun Mountain, was made in November 1905 in Beijing.[17] For the next decade the production companies were mainly foreign-owned, and the domestic film industry was centered on Shanghai, a thriving entrepot and the largest city in the Far East. In 1913, the first independent Chinese screenplay, The Difficult Couple, was filmed in Shanghai by Zheng Zhengqiu and Zhang Shichuan.[18] Zhang Shichuan then set up the first Chinese-owned film production company in 1916. The first full-length feature film was Yan Ruisheng (閻瑞生) released in 1921. which was a docudrama about the killing of a Shanghai courtesan, although it was too crude a film to ever be considered commercially successful.[5] During the 1920s film technicians from the United States trained Chinese technicians in Shanghai, and American influence continued to be felt there for the next two decades.[18] Since film was still in its earliest stages of development, most Chinese silent films at this time were only comic skits or operatic shorts, and training was minimal at a technical aspect due to this being a period of experimental film.[5]

Later, after trial and error, China was able to draw inspiration from its own traditional values and began producing martial arts films, with the first being Burning of Red Lotus Temple (1928). Burning of Red Lotus Temple was so successful at the box office, the Star Motion Pictures (Mingxing) production has since filmed 18 sequels, marking the beginning of China's esteemed martial arts films.[5] It was during this period that some of the more important production companies first came into being, notably Mingxing and the Shaw brothers' Tianyi ("Unique"). Mingxing, founded by Zheng Zhengqiu and Zhang Shichuan in 1922, initially focused on comic shorts, including the oldest surviving complete Chinese film, Laborer's Love (1922).[19][20][21] This soon shifted, however, to feature-length films and family dramas including Orphan Rescues Grandfather (1923).[19] Meanwhile, Tianyi shifted their model towards folklore dramas, and also pushed into foreign markets; their film White Snake (1926)[lower-alpha 1] proved a typical example of their success in the Chinese communities of Southeast Asia.[19] In 1931, the first Chinese sound film Sing-Song Girl Red Peony was made, the product of a cooperation between the Mingxing Film Company's image production and Pathé Frères's sound technology. However, the sound was disc-recorded, which was then played in the theatre in-sync with the action on the screen. The first sound-on-film talkie made in China was either Spring on Stage (歌場春色) by Tianyi, or Clear Sky After Storm by Great China Studio and Jinan Studio.[23]

Leftist Movement

However, the first truly important Chinese films were produced beginning in the 1930s, with the advent of the "progressive" or "left-wing" movement, like Cheng Bugao's Spring Silkworms (1933), Wu Yonggang's The Goddess (1934), and Sun Yu's The Big Road (1935). These films were noted for their emphasis on class struggle and external threats (i.e. Japanese aggression), as well as on their focus on common people, such as a family of silk farmers in Spring Silkworms and a prostitute in The Goddess.[17] In part due to the success of these kinds of films, this post-1930 era is now often referred to as the first "golden period" of Chinese cinema.[17] The Leftist cinematic movement often revolved around the Western-influenced Shanghai, where filmmakers portrayed the struggling lower class of an overpopulated city.[24]

Three production companies dominated the market in the early to mid- 1930s: the newly formed Lianhua ("United China"),[lower-alpha 2] the older and larger Mingxing and Tianyi.[25] Both Mingxing and Lianhua leaned left (Lianhua's management perhaps more so),[17] while Tianyi continued to make less socially conscious fare.

The period also produced the first big Chinese movie stars, such as Hu Die, Ruan Lingyu, Li Lili, Chen Yanyan, Zhou Xuan, Zhao Dan and Jin Yan. Other major films of the period include Love and Duty (1931), Little Toys (1933), New Women (1934), Song of the Fishermen (1934), Plunder of Peach and Plum (1934), Crossroads (1937), and Street Angel (1937). Throughout the 1930s, the Nationalists and the Communists struggled for power and control over the major studios; their influence can be seen in the films the studios produced during this period.

Japanese Occupation and World War II

The Japanese invasion of China in 1937, in particular the Battle of Shanghai, ended this golden run in Chinese cinema. All production companies except Xinhua Film Company ("New China") closed shop, and many of the filmmakers fled Shanghai, relocating to Hong Kong, the wartime Nationalist capital Chongqing, and elsewhere. The Shanghai film industry, though severely curtailed, did not stop however, thus leading to the "Solitary Island" period (also known as the "Sole Island" or "Orphan Island"), with Shanghai's foreign concessions serving as an "island" of production in the "sea" of Japanese-occupied territory. It was during this period that artists and directors who remained in the city had to walk a fine line between staying true to their leftist and nationalist beliefs and Japanese pressures. Director Bu Wancang's Mulan Joins the Army (1939), with its story of a young Chinese peasant fighting against a foreign invasion, was a particularly good example of Shanghai's continued film-production in the midst of war.[19][26] This period ended when Japan declared war on the Western allies on December 7, 1941; the solitary island was finally engulfed by the sea of the Japanese occupation. With the Shanghai industry firmly in Japanese control, films like the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere-promoting Eternity (1943) were produced.[19] At the end of World War II, one of the most controversial Japanese-authorized companies, Manchukuo Film Association, would be separated and integrated into Chinese cinema.[27]

Second Golden Age

The film industry continued to develop after 1945. Production in Shanghai once again resumed as a new crop of studios took the place that Lianhua and Mingxing studios had occupied in the previous decade. In 1945, Cai Chusheng returned to Shanghai to revive the Lianhua name as the "Lianhua Film Society with Shi Dongshan, Meng Junmou and Zheng Junli."[28] This in turn became Kunlun Studios which would go on to become one of the most important studios of the era, (Kunlun Studios merged with seven other studios to form Shanghai film studio in 1949) putting out the classics The Spring River Flows East (1947), Myriad of Lights (1948), Crows and Sparrows (1949) and San Mao, The Little Vagabond (1949).[29] Many of these films showed the disillusionment with the oppressive rule of Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist Party and the struggling oppression of nation by war. The Spring River Flows East, a three-hour-long two-parter directed by Cai Chusheng and Zheng Junli, was a particularly strong success. Its depiction of the struggles of ordinary Chinese during the Second Sino-Japanese war, replete with biting social and political commentary, struck a chord with audiences of the time.

Meanwhile, companies like the Wenhua Film Company ("Culture Films"), moved away from the leftist tradition and explored the evolution and development of other dramatic genres. Wenhua treated postwar problems in universalistic and humanistic ways, avoiding the family narrative and melodramatic formulae. Excellent examples of Wenhua's fare are its first two postwar features, Unending Emotions (1947) and Fake Bride, Phony Bridegroom (1947).[30] Another memorable Wenhua film is Long Live the Missus (1947), like Unending Emotions with an original screenplay by writer Eileen Chang. Wenhua's romantic drama Spring in a Small Town (1948), a film by director Fei Mu shortly prior to the revolution, is often regarded by Chinese film critics as one of the most important films in the history of Chinese cinema, in 2005, Hong Kong film awards it as the best 100 years of film.[31] Ironically, it was precisely its artistic quality and apparent lack of "political grounding" that led to its labeling by the Communists as rightist or reactionary, and the film was quickly forgotten by those on the mainland following the Communist victory in China in 1949.[32] However, with the China Film Archive's re-opening after the Cultural Revolution, a new print was struck from the original negative, allowing Spring of the Small Town to find a new and admiring audience and to influence an entire new generation of filmmakers. Indeed, an acclaimed remake was made in 2002 by Tian Zhuangzhuang. A Chinese Peking opera film, A Wedding in the Dream (1948), by the same director(Fei Mu), was the first Chinese color film.

Early Communist Era

With the communist revolution in China in 1949, the government saw motion pictures as an important mass production art form and tool for propaganda. Starting from 1951, pre-1949 Chinese films, Hollywood and Hong Kong productions were banned as the Communist Party of China sought to tighten control over mass media, producing instead movies centering on peasants, soldiers and workers, such as Bridge (1949) and The White Haired Girl (1950).[33] One of the production bases in the middle of all the transition was the Changchun Film Studio.

The private studios in Shanghai, including Kunming, Wenhua, Guotai and Datong, were encouraged to make new films from 1949 to 1951. They made approximately 47 films during this period, but soon ran into trouble, owing to the furore over the Kunlun-produced drama The Life of Wu Xun (1950), directed by Sun Yu and starring veteran Zhao Dan. The feature was accused in an anonymous article in People's Daily in May 1951 of spreading feudal ideas. After the article was revealed to be penned by Mao Zedong, the film was banned, a Film Steering Committee was formed to "re-educate" the film industry and within two years, these private studios were all incorporated into the state-run Shanghai Film Studio.[33][34]

The Communist regime solved the problem of a lack of film theaters by building mobile projection units which could tour the remote regions of China, ensuring that even the poorest could have access to films. By 1965 there were around 20,393 such units.[33] The number of movie-viewers hence increased sharply, partly bolstered by the fact that film tickets were given out to work units and attendance was compulsory,[34] with admissions rising from 47 million in 1949 to 4.15 billion in 1959.[35] In the 17 years between the founding of the People's Republic of China and the Cultural Revolution, 603 feature films and 8,342 reels of documentaries and newsreels were produced, sponsored mostly as Communist propaganda by the government.[36] For example, in Guerrilla on the Railroad (铁道游击队), dated 1956, the Chinese Communist Party was depicted as the primary resistance force against the Japanese in the war against invasion.[37] Chinese filmmakers were sent to Moscow to study the Soviet socialist realism style of filmmaking.[35] The Beijing Film Academy established in 1950 and in 1956, the Beijing Film Academy was officially opened. One important film of this era is This Life of Mine (1950), directed by Shi Hu, which follows an old beggar reflecting on his past life as a policeman working for the various regimes since 1911.[38][39] The first widescreen Chinese film was produced in 1960. Animated films using a variety of folk arts, such as papercuts, shadow plays, puppetry, and traditional paintings, also were very popular for entertaining and educating children. The most famous of these, the classic Havoc in Heaven (two parts, 1961, 4), was made by Wan Laiming of the Wan Brothers and won Outstanding Film award at the London International Film Festival.

The thawing of censorship in 1956–57 (known as the Hundred Flowers Campaign) and the early 1960s led to more indigenous Chinese films being made which were less reliant on their Soviet counterparts.[40] During this campaign the sharpest criticisms came from the satirical comedies of Lü Ban. Before the New Director Arrives exposes the hierarchical relationships occurring between the cadres, while his next film, The Unfinished Comedy (1957), was labelled as a "poisonous weed" during the Anti-Rightist Movement and Lü was banned from directing for life.[41][42]The Unfinished Comedy was only screened after Mao's death. Other noteworthy films produced during this period were adaptations of literary classics, such as Sang Hu's The New Year's Sacrifice (1956; adapted from a Lu Xun story) and Shui Hua's The Lin Family Shop (1959; adapted from a Mao Dun story). The most prominent filmmaker of this era was Xie Jin, whose three films in particular, Woman Basketball Player No. 5 (1957), The Red Detachment of Women (1961) and Two Stage Sisters (1964), exemplify China's increased expertise at filmmaking during this time. Films made during this period are polished and exhibit high production value and elaborate sets.[43] While Beijing and Shanghai remained the main centers of production, between 1957–60 the government built regional studios in Guangzhou, Xi'an and Chengdu to encourage representations of ethnic minorities in films. Chinese cinema began to directly address the issue of such ethnic minorities during the late 1950s and early 1960s, in films like Five Golden Flowers (1959), Third Sister Liu (1960), Serfs (1963), Ashima (1964).[44][45]

Films of the Cultural Revolution

During the Cultural Revolution, the film industry was severely restricted. Almost all previous films were banned, and only a few new ones were produced, the so-called "revolutionary model operas". The most notable of these was a ballet version of the revolutionary opera The Red Detachment of Women, directed by Pan Wenzhan and Fu Jie in 1970. Feature film production came almost to a standstill in the early years from 1967 to 1972. Movie production revived after 1972 under the strict jurisdiction of the Gang of Four until 1976, when they were overthrown. The few films that were produced during this period, such as 1975's Breaking with Old Ideas, were highly regulated in terms of plot and characterization.[46]

In the years immediately following the Cultural Revolution, the film industry again flourished as a medium of popular entertainment. Production rose steadily, from 19 features in 1977 to 125 in 1986.[47] Domestically produced films played to large audiences, and tickets for foreign film festivals sold quickly. The industry tried to revive crowds by making more innovative and "exploratory" films like their counterparts in the West.

In the 1980s the film industry fell on hard times, faced with the dual problems of competition from other forms of entertainment and concern on the part of the authorities that many of the popular thriller and martial arts films were socially unacceptable. In January 1986 the film industry was transferred from the Ministry of Culture to the newly formed Ministry of Radio, Cinema, and Television to bring it under "stricter control and management" and to "strengthen supervision over production."

The end of the Cultural Revolution brought the release of "scar dramas", which depicted the emotional traumas left by this period. The best-known of these is probably Xie Jin's Hibiscus Town (1986), although they could be seen as late as the 1990s with Tian Zhuangzhuang's The Blue Kite (1993). In the 1980s, open criticism of certain past Communist Party policies was encouraged by Deng Xiaoping as a way to reveal the excesses of the Cultural Revolution and the earlier Anti-Rightist Campaign, also helping to legitimize Deng's new policies of "reform and opening up." For instance, the Best Picture prize in the inaugural 1981 Golden Rooster Awards was given to two "scar dramas", Evening Rain (Wu Yonggang, Wu Yigong, 1980) and Legend of Tianyun Mountain (Xie Jin, 1980).[48]

Many scar dramas were made by members of the Fourth Generation whose own careers or lives had suffered during the events in question, while younger, Fifth Generation directors such as Tian tended to focus on less controversial subjects of the immediate present or the distant past. Official enthusiasm for scar dramas waned by the 1990s when younger filmmakers began to confront negative aspects of the Mao era. The Blue Kite, though sharing a similar subject as the earlier scar dramas, was more realistic in style, and was made only through obfuscating its real script. Shown abroad, it was banned from release in mainland China, while Tian himself was banned from making any films for nearly a decade afterward. After the 1989 Tiananmen Square Protests, few if any scar dramas were released domestically in mainland China.

Rise of the Fifth Generation

Beginning in the mid-late 1980s, the rise of the so-called Fifth Generation of Chinese filmmakers brought increased popularity of Chinese cinema abroad. Most of the filmmakers who made up the Fifth Generation had graduated from the Beijing Film Academy in 1982 and included Zhang Yimou, Tian Zhuangzhuang, Chen Kaige, Zhang Junzhao, Li Shaohong, Wu Ziniu and others. These graduates constituted the first group of filmmakers to graduate since the Cultural Revolution and they soon jettisoned traditional methods of storytelling and opted for a more free and unorthodox symbolic approach.[49] After the so-called scar literature in fiction had paved the way for frank discussion, Zhang Junzhao's One and Eight (1983) and Chen Kaige's Yellow Earth (1984) in particular were taken to mark the beginnings of the Fifth Generation.[lower-alpha 3] The most famous of the Fifth Generation directors, Chen Kaige and Zhang Yimou, went on to produce celebrated works such as King of the Children (1987), Ju Dou (1989), Raise the Red Lantern (1991) and Farewell My Concubine (1993), which were not only acclaimed by Chinese cinema-goers but by the Western arthouse audience. Tian Zhuangzhuang's films, though less well known by Western viewers, were well noted by directors such as Martin Scorsese. It was during this period that Chinese cinema began reaping the rewards of international attention, including the 1988 Golden Bear for Red Sorghum, the 1992 Golden Lion for The Story of Qiu Ju, the 1993 Palme d'Or for Farewell My Concubine, and three Best Foreign Language Film nominations from the Academy Awards.[50] All these award-winning films starred actress Gong Li, who became the Fifth Generation's most recognizable star, especially to international audiences.

Diverse in style and subject, the Fifth Generation directors' films ranged from black comedy (Huang Jianxin's The Black Cannon Incident, 1985) to the esoteric (Chen Kaige's Life on a String, 1991), but they share a common rejection of the socialist-realist tradition worked by earlier Chinese filmmakers in the Communist era. Other notable Fifth Generation directors include Wu Ziniu, Hu Mei, Li Shaohong and Zhou Xiaowen. Fifth Generation filmmakers reacted against the ideological purity of Cultural Revolution cinema. By relocating to regional studios, they began to explore the actuality of local culture in a somewhat documentarian fashion. Instead of stories depicting heroic military struggles, the films were built out of the drama of ordinary people's daily lives. They also retained political edge, but aimed at exploring issues rather than recycling approved policy. While Cultural Revolution films used character, the younger directors favored psychological depth along the lines of European cinema. They adopted complex plots, ambiguous symbolism, and evocative imagery.[51] Some of their bolder works with political overtones were banned by Chinese authorities.

These films came with a creative genres of stories, new style of shooting as well, directors utilized extensive color and long shots to present and explore history and structure of national culture. As a result of the new films being so intricate, the films were for more educated audiences than anything. The new style was profitable for some and helped filmmakers to make strides in the business. It allowed directors to get away from reality and show their artistic sense.[52]

The Fourth Generation also returned to prominence. Given their label after the rise of the Fifth Generation, these were directors whose careers were stalled by the Cultural Revolution and who were professionally trained prior to 1966. Wu Tianming, in particular, made outstanding contributions by helping to finance major Fifth Generation directors under the auspices of the Xi'an Film Studio (which he took over in 1983), while continuing to make films like Old Well (1986) and The King of Masks (1996).

The Fifth Generation movement ended in part after the 1989 Tiananmen Incident, although its major directors continued to produce notable works. Several of its filmmakers went into self-imposed exile: Wu Tianming moved to the United States (but later returned), Huang Jianxin left for Australia, while many others went into television-related works.

Main Melody Dramas

During a period where socialist dramas were beginning to lose viewership, the Chinese government began to involve itself deeper into the world of popular culture and cinema by creating the official genre of the "main melody" (主旋律), inspired by Hollywood's strides in musical dramas.[53] In 1987, the Ministry of Radio, Film and Television issued a statement encouraging the making of movies which emphasizes the main melody to "invigorate national spirit and national pride".[54] The expression "main melody" refers to the musical term leitmotif, that translates to the "theme of our times", which scholars suggest is representative of China's socio-political climate and cultural context of popular cinema.[55] These main melody films (主旋律电影), still produced regularly in modern times, try to emulate the commercial mainstream by the use of Hollywood-style music and special effects. A significant feature of these films is the incorporation of a "red song", which is a song written as propaganda to support the People's Republic of China.[56] By revolving the film around the motif of a red song, the film is able to gain traction at the box office as songs are generally thought to be more accessible than a film. Theoretically, once the red song dominates the charts, it will stir interest in the film that which it accompanies.[57]

Main melody dramas are often subsidized by the state and have free access to government and military personnel.[58] The Chinese government spends between "one and two million RMBs" annually to support the production of films in the main melody genre. August 1st Film Studio, the film and TV production arm of the People's Liberation Army, is a studio which produces main melody cinema. Main melody films, which often depict past military engagements or are biopics of first-generation CCP leaders, have won several Best Picture prizes at the Golden Rooster Awards.[59] Some of the more famous main melody dramas include the ten-hour epic Decisive Engagement (大决战, 1991), directed by Cai Jiawei, Yang Guangyuan and Wei Lian; The Opium War (1997), directed by Xie Jin; and The Founding of a Republic (2009), directed by Han Sanping and Fifth Generation director Huang Jianxin.[60] The Founding of an Army (2017) was commissioned by the government to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the People's Liberation Army, and is the third instalment in The Founding of a Republic series.[61] The film featured many young Chinese pop singers that are already well-established in the industry, including Li Yifeng, Liu Haoran, and Lay Zhang, so as to further the film's reputation as a main melody drama.

Sixth Generation

The post-1990 era has been labelled the "return of the amateur filmmaker" as state censorship policies after the Tiananmen Square demonstrations produced an edgy underground film movement loosely referred to as the Sixth Generation. Owing to the lack of state funding and backing, these films were shot quickly and cheaply, using materials like 16 mm film and digital video and mostly non-professional actors and actresses, producing a documentary feel, often with long takes, hand-held cameras, and ambient sound; more akin to Italian neorealism and cinéma vérité than the often lush, far more considered productions of the Fifth Generation.[50] Unlike the Fifth Generation, the Sixth Generation brings a more creative individualistic, anti-romantic life-view and pays far closer attention to contemporary urban life, especially as affected by disorientation, rebellion[62] and dissatisfaction with China's contemporary social marketing economic tensions and comprehensive cultural background.[63] Many were made with an extremely low budget (an example is Jia Zhangke, who shoots on digital video, and formerly on 16 mm; Wang Xiaoshuai's The Days (1993) were made for US$10,000[63]). The title and subjects of many of these films reflect the Sixth Generation's concerns. The Sixth Generation takes an interest in marginalized individuals and the less represented fringes of society. For example, Zhang Yuan's hand-held Beijing Bastards (1993) focuses on youth punk subculture, featuring artists like Cui Jian, Dou Wei and He Yong frowned upon by many state authorities,[64] while Jia Zhangke's debut film Xiao Wu (1997) concerns a provincial pickpocket.

As the Sixth Generation gained international exposure, many subsequent movies were joint ventures and projects with international backers, but remained quite resolutely low-key and low budget. Jia's Platform (2000) was funded in part by Takeshi Kitano's production house,[65] while his Still Life was shot on HD video. Still Life was a surprise addition and Golden Lion winner of the 2006 Venice International Film Festival. Still Life, which concerns provincial workers around the Three Gorges region, sharply contrasts with the works of Fifth Generation Chinese directors like Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige who were at the time producing House of Flying Daggers (2004) and The Promise (2005). It featured no star of international renown and was acted mostly by non-professionals.

Many Sixth Generation films have highlighted the negative attributes of China's entry into the modern capitalist market. Li Yang's Blind Shaft (2003) for example, is an account of two murderous con-men in the unregulated and notoriously dangerous mining industry of northern China.[66] (Li refused the tag of Sixth Generation, although admitted he was not Fifth Generation).[62] While Jia Zhangke's The World (2004) emphasizes the emptiness of globalization in the backdrop of an internationally themed amusement park.[67]

Some of the more prolific Sixth Generation directors to have emerged are Wang Xiaoshuai (The Days, Beijing Bicycle, So Long, My Son), Zhang Yuan (Beijing Bastards, East Palace West Palace), Jia Zhangke (Xiao Wu, Unknown Pleasures, Platform, The World, A Touch of Sin, Mountains May Depart, Ash is Purest White), He Jianjun (Postman) and Lou Ye (Suzhou River, Summer Palace). One young director who does not share most of the concerns of the Sixth Generation is Lu Chuan (Kekexili: Mountain Patrol, 2004; City of Life and Death, 2010).

Notable ‘sixth generation’ directors: Jia Zhangke and Zhang Meng

In the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, two of China's Sixth generation filmmakers, Jia Zhangke and Zhang Meng – whose grim works transformed Chinese cinema in the 1990s – showed on the French Riviera. While both directors represent Chinese cinema, their profiles are quite different. The 49 year old Jia set up the Pingyao International Film Festival in 2017 and on the other hand is Zhang, a 56-year-old film school professor who spent years working on government commissions and domestic TV shows after struggling with his own projects. Despite their different profiles, they mark an important cornerstone in Chinese Cinema and are both credited with bringing Chinese movies to the international big screen. Chinese director Jia Zhangke's latest film Ash Is Purest White has been selected to compete in the official competition for the Palme d'Or of the 71st Cannes Film Festival, the highest prize awarded at the film festival. It is Jia’s fifth movie, a gangster revenge drama that is his most expensive and mainstream film to date. Back in 2013, Jia won Best Screenplay Award for A Touch of Sin, following nominations for Unknown Pleasures in 2002 and 24 City in 2008. In 2014, he was a member of the official jury and the following year his film Mountains May Depart was nominated. According to entertainment website Variety, a record number of Chinese films were submitted this year but only Jia's romantic drama was selected to compete for the Palme d'Or. Meanwhile, Zhang will make his debut at Cannes with The Pluto Moment, a slow-moving relationship drama about a team of filmmakers scouting for locations and musical talent in China’s rural hinterland. The film is Zhang’s highest profile production so far, as it stars actor Wang Xuebing in the leading role. The film was partly financed by iQiyi, the company behind one of China’s most popular online video browsing sharing sites.[68]

Generation Independent Movement

There is a growing number of independent seventh or post-Sixth Generation filmmakers making films with extremely low budgets and using digital equipment. They are the so-called dGeneration (for digital).[69] These films, like those from Sixth Generation filmmakers, are mostly made outside the Chinese film system and are shown mostly on the international film festival circuit. Ying Liang and Jian Yi are two of these generation filmmakers. Ying's Taking Father Home (2005) and The Other Half (2006) are both representative of the generation trends of the feature film. Liu Jiayin made two dGeneration feature films, Oxhide (2004) and Oxhide II (2010), blurring the line between documentary and narrative film. Oxhide, made by Liu when she was a film student, frames herself and her parents in their claustrophobic Beijing apartment in a narrative praised by critics. An Elephant Sitting Still was another great work considered to be one of the greatest films ever made as a film debut and the last film by the late Hu Bo.[70]

New Documentary Movement

Two decades of reform and commercialization have brought dramatic social changes in mainland China, reflected not only in fiction film but in a growing documentary movement. Wu Wenguang's 70-minute Bumming in Beijing: The Last Dreamers (1990) is now seen as one of the first works of this "New Documentary Movement" (NDM) in China.[71][72] Bumming, made between 1988 and 1990, contains interviews with five young artists eking out a living in Beijing, subject to state authorized tasks. Shot using a camcorder, the documentary ends with four of the artists moving abroad after the 1989 Tiananmen Protests.[73] Dance with the Farm Workers (2001) is another documentary by Wu.[74]

Another internationally acclaimed documentary is Wang Bing's nine-hour tale of deindustrialization Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2003). Wang's subsequent documentaries, He Fengming (2007), Crude Oil (2008), Man with no name (2009), Three Sisters (2012) and Feng ai (2013), cemented his reputation as a leading documentarist of the movement.[75]

Li Hong, the first woman in the NDM, in Out of Phoenix Bridge (1997) relates the story of four young women, who moving from rural areas to the big cities like millions of other men and women, have come to Beijing to make a living.

The New Documentary Movement in recent times has overlapped with the dGeneration filmmaking, with most documentaries being shot cheaply and independently in the digital format. Xu Xin's Karamay (2010), Zhao Liang's Behemoth, Huang Weikai's Disorder (2009), Zhao Dayong's Ghost Town (2009), Du Haibing's 1428 (2009), Xu Tong's Fortune Teller (2010) and Li Ning’s Tape (2010) were all shot in digital format. All had made their impact in the international documentary scene and the use of digital format allows for works of vaster lengths.

Chinese Animated Movies

Early ~ 1950s

Inspired by the success of Disney animation, the self-taught pioneers Wan brothers, Wan Laiming and Wan Guchan, made the first Chinese animated short in the 1920s, thus inaugurating the history of Chinese animation. (Chen Yuanyuan 175)[76]

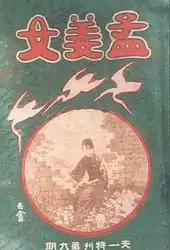

In 1937, the Wan brothers decided to produce 《铁扇公主》 Princess Iron Fan, which was the first Chinese animated feature film and the fourth, after the American feature films Snow White, Gulliver’s Travels, and The Adventure of Pinocchio. It was at this time that Chinese animation as an art form had risen to prominence on the world stage. Completed in 1941, the film was released under China United Pictures and aroused a great response in Asia. Japanese animator Shigeru Tezuka once said that he gave up medicine after watching the cartoon and decided to pursue animation.

1950s ~ 1980s

During this golden era, Chinese animation had developed a variety of styles, including ink animation, shadow play animation, puppet animation, and so on. Some of the most representative works are 《大闹天宫》 Uproar in Heaven, 《哪吒闹海》 Nezha's Rebellion in the Sea and《天书奇谈》 Heavenly Book, which have also won lofty praise and numerous awards in the world.

1980s ~ 1990s

After Deng Xiaoping’s Reform Period and the “opening up” of China, the movies《葫芦兄弟》 Calabash Brothers, 《黑猫警长》Black Cat Sheriff, 《阿凡提》Avanti Story and other impressive animated movies were released. However, at this time, China still favored the Japanese’s more unique, American and European-influenced animated works over the less-advanced domestic ones.

1990s ~ 2000s

In the 1990s, digital production methods replaced manual hand-drawing methods; however, even with the use of advanced technology, none of the animated works were considered to be a breakthrough film. Animated films that tried to cater to all age groups, such as Lotus Lantern and Storm Resolution, did not attract much attention. The only animated works that seemed to achieve popularity were the ones for catered for children, such as Pleasant Goat and Wolfy 《喜羊羊与灰太狼》.

2010s ~ Present

During this period, the technical level of Chinese domestic animation production has been established comprehensively, and 3D animation films have become the mainstream. However, as more and more foreign films (such as ones from Japan, Europe, and the United States) are being imported into China, Chinese animated works is left in the shadows of these animated foreign films.

It is only with the release of 《西游记之大圣归来》Journey to the West: The Return of Monkey King in 2015, a live-action film where CGI was extensively used in its production, that Chinese animated works took back the rein. This movie was a big hit in 2015 and broke the gross record of Chinese domestic animated movies with CN¥956 million at China’s box office.

After the success of Journey to the West, several other high-quality animated films were released, such as 《风雨咒》 Wind Language Curse and 《白蛇缘起》 White Snake. Though none of these movies made headway in regards to the box office and popularity aspect, it did make filmmakers more and more interested in animated works.

This all changed with the breakthrough animated film, 《哪吒之魔童降世》Nezha. Released in 2019, it became the second highest-grossing film of all time in China. It was with this film that Chinese animated films, as a medium, has finally broken the notion in China that domestic animated films are only for children. With Nezha (2019), Chinese animation has now come to known to a veritable source of entertainment for all ages.

New Models and the New Chinese Cinema

Commercial Successes

With China's liberalization in the late 1970s and its opening up to foreign markets, commercial considerations have made its impact in post-1980s filmmaking. Traditionally arthouse movies screened seldom make enough to break even. An example is Fifth Generation director Tian Zhuangzhuang's The Horse Thief (1986), a narrative film with minimal dialog on a Tibetan horse thief. The film, showcasing exotic landscapes, was well received by Chinese and some Western arthouse audiences, but did poorly at the box office.[77] Tian's later The Warrior and the Wolf (2010) was a similar commercial failure.[78] Prior to these, there were examples of successful commercial films in the post-liberalization period. One was the romance film Romance on the Lu Mountain (1980), which was a success with older Chinese. The film broke the Guinness Book of Records as the longest-running film on a first run. Jet Li's cinematic debut Shaolin Temple (1982) was an instant hit at home and abroad (in Japan and the Southeast Asia, for example).[79] Another successful commercial film was Murder in 405 (405谋杀案, 1980), a murder thriller.[80]

Feng Xiaogang's The Dream Factory (1997) was heralded as a turning point in Chinese movie industry, a hesui pian (Chinese New Year-screened film) which demonstrated the viability of the commercial model in China's socialist market society. Feng has become the most successful commercial director in the post-1997 era. Almost all his films made high returns domestically[81] while he used ethnic Chinese co-stars like Rosamund Kwan, Jacqueline Wu, Rene Liu and Shu Qi to boost his films' appeal.

In the decade following 2010, owing to the influx of Hollywood films (though the number screened each year is curtailed), Chinese domestic cinema faces mounting challenges. The industry is growing and domestic films are starting to achieve the box office impact of major Hollywood blockbusters. However, not all domestic films are successful financially. In January 2010 James Cameron's Avatar was pulled out from non-3D theaters for Hu Mei's biopic Confucius, but this move led to a backlash on Hu's film.[82] Zhang Yang's 2005 Sunflower also made little money, but his earlier, low-budget Spicy Love Soup (1997) grossed ten times its budget of ¥3 million.[83] Likewise, the 2006 Crazy Stone, a sleeper hit, was made for just 3 million HKD/US$400,000. In 2009–11, Feng's Aftershock (2009) and Jiang Wen's Let the Bullets Fly (2010) became China's highest grossing domestic films, with Aftershock earning ¥670 million (US$105 million)[84] and Let the Bullets Fly ¥674 million (US$110 million).[85] Lost in Thailand (2012) became the first Chinese film to reach ¥1 billion at the Chinese box office and Monster Hunt (2015) became the first to reach CN¥2 billion . As of November 2015, 5 of the top 10 highest-grossing films in China are domestic productions. On February 8, 2016, the Chinese box office set a new single-day gross record, with CN¥660 million , beating the previous record of CN¥425 million on July 18, 2015.[86] Also in February 2016, The Mermaid, directed by Stephen Chow, became the highest-grossing film in China, overtaking Monster Hunt.[87] It is also the first film to reach CN¥3 billion .[88]

Under the influence of Hollywood science fiction movies like Prometheus, published on June 8, 2012, such genres especially the space science films have risen rapidly in the Chinese film market in recent years. On February 5, 2019, the film The Wandering Earth directed by Frant Kwo reached $699.8 million worldwide, which became the third highest-grossing film in the history of Chinese cinema.

Other Directors

He Ping is a director of mostly Western-like films set in Chinese locale. His Swordsmen in Double Flag Town (1991) and Sun Valley (1995) explore narratives set in the sparse terrain of West China near the Gobi Desert. His historical drama Red Firecracker, Green Firecracker (1994) won a myriad of prizes home and abroad.

Recent cinema has seen Chinese cinematographers direct some acclaimed films. Other than Zhang Yimou, Lü Yue made Mr. Zhao (1998), a black comedy film well received abroad. Gu Changwei's minimalist epic Peacock (2005), about a quiet, ordinary Chinese family with three very different siblings in the post-Cultural Revolution era, took home the Silver Bear prize for 2005 Berlin International Film Festival. Hou Yong is another cinematographer who made films (Jasmine Women, 2004) and TV series. There are actors who straddle the dual roles of acting and directing. Xu Jinglei, a popular Chinese actress, has made six movies to date. Her second film Letter from an Unknown Woman (2004) landed her the San Sebastián International Film Festival Best Director award. Another popular actress and director is Zhao Wei, whose directorial debut So Young (2013) was a huge box office and critical success.

The most highly regarded Chinese actor-director is undoubtedly Jiang Wen, who has directed several critically acclaimed movies while following on his acting career. His directorial debut, In the Heat of the Sun (1994) was the first PRC film to win Best Picture at the Golden Horse Film Awards held in Taiwan. His other films, like Devils on the Doorstep (2000, Cannes Grand Prix) and Let the Bullets Fly (2010), were similarly well received. By the early 2011, Let the Bullets Fly had become the highest grossing domestic film in China's history.[89][90]

Chinese International Cinema and Successes Abroad

Since the late 1980s and progressively in the 2000s, Chinese films have enjoyed considerable box office success abroad. Formerly viewed only by cineastes, its global appeal mounted after the international box office and critical success of Ang Lee's period martial arts film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon which won Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 2000. This multi-national production increased its appeal by featuring stars from all parts of the Chinese-speaking world. It provided an introduction to Chinese cinema (and especially the wuxia genre) for many and increased the popularity of many earlier Chinese films. To date Crouching Tiger remains the most commercially successful foreign-language film in U.S. history.

Similarly, in 2002, Zhang Yimou's Hero was another international box office success. Its cast featured famous actors from the Mainland China and Hong Kong who were also known to some extent in the West, including Jet Li, Zhang Ziyi, Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung Chiu-Wai. Despite criticisms by some that these two films pander somewhat to Western tastes, Hero was a phenomenal success in most of Asia and topped the U.S. box office for two weeks, making enough in the U.S. alone to cover the production costs.

Other films such as Farewell My Concubine, 2046, Suzhou River, The Road Home and House of Flying Daggers were critically acclaimed around the world. The Hengdian World Studios can be seen as the "Chinese Hollywood", with a total area of up to 330 ha. and 13 shooting bases, including a 1:1 copy of the Forbidden City.

.jpg.webp)

The successes of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero make it difficult to demarcate the boundary between "Mainland Chinese" cinema and a more international-based "Chinese-language cinema". Crouching Tiger, for example, was directed by a Taiwan-born American director (Ang Lee) who works often in Hollywood. Its pan-Chinese leads include Mainland Chinese (Zhang Ziyi), Hong Kong (Chow Yun-Fat), Taiwan (Chang Chen) and Malaysian (Michelle Yeoh) actors and actresses; the film was co-produced by an array of Chinese, American, Hong Kong, and Taiwan film companies. Likewise, Lee's Chinese-language Lust, Caution (2007) drew a crew and cast from Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, and includes an orchestral score by French composer Alexandre Desplat. This merging of people, resources and expertise from the three regions and the broader East Asia and the world, marks the movement of Chinese-language cinema into a domain of large scale international influence. Other examples of films in this mold include The Promise (2005), The Banquet (2006), Fearless (2006), The Warlords (2007), Bodyguards and Assassins (2009) and Red Cliff (2008-09). The ease with which ethnic Chinese actresses and actors straddle the mainland and Hong Kong has significantly increased the number of co-productions in Chinese-language cinema. Many of these films also feature South Korean or Japanese actors to appeal to their East Asian neighbours. Some artistes originating from the mainland, like Hu Jun, Zhang Ziyi, Tang Wei and Zhou Xun, obtained Hong Kong residency under the Quality Migrant Admission Scheme and have acted in many Hong Kong productions.[91]

Industry

Box Office and Screens

In 2010, Chinese cinema was the third largest film industry by number of feature films produced annually.[92] In 2013, China's gross box office was ¥21.8 billion (US$3.6 billion), the second-largest film market in the world by box office receipts.[93] In January 2013, Lost in Thailand (2012) became the first Chinese film to reach ¥1 billion at the box office.[94] As of May 2013, 7 of the top 10 highest-grossing films in China were domestic productions.[95] As of 2014, around half of all tickets are sold online, with the largest ticket selling sites being Maoyan.com (82 million), Gewara.com (45 million) and Wepiao.com (28 million).[96] In 2014, Chinese films earned ¥1.87 billion outside China.[97] By December 2013 there were 17,000 screens in the country.[98] By January 6, 2014, there were 18,195 screens in the country.[93] Greater China has around 251 IMAX theaters.[99] There were 299 cinema chains (252 rural, 47 urban), 5,813 movie theaters and 24,317 screens in the country in 2014.[3]

The country added about 8,035 screens in 2015 (at an average of 22 new screens per day, increasing its total by about 40% to around 31,627 screens, which is about 7,373 shy of the number of screens in the United States.[100][101] Chinese films accounted for 61.48% of ticket sales in 2015 (up from 54% last year) with more than 60% of ticket sales being made online. Average ticket price was down about 2.5% to $5.36 in 2015.[100] It also witnessed 51.08% increase in admissions, with 1.26 billion people buying tickets to the cinema in 2015.[101] Chinese films grossed US$427 million overseas in 2015.[102] During the week of the 2016 Chinese New Year, the country set a new record for the highest box office gross during one week in one territory with US$548 million , overtaking the previous record of US$529.6 million of December 26, 2015 to January 1, 2016 in the United States and Canada.[103] Chinese films grossed CN¥3.83 billion (US$550 million ) in foreign markets in 2016.[2]

| Year | Gross (in billions of yuans) | Domestic share | Tickets sold (in millions) | Number of screens |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | less than 1[104] | |||

| 2004 | 1.5[105] | |||

| 2005 | 2[105] | 60%[106] | 157.2[107][108] | 4,425[109] |

| 2006 | 2.67[105] | 176.2[107][108] | 3,034[110] or 4,753[109] | |

| 2007 | 3.33[105] | 55%[106] | 195.8[107][108] | 3,527[110] or 5,630[109] |

| 2008 | 4.34[105] | 61%[106] | 209.8[107][108] | 4,097[110] or 5,722[109] |

| 2009 | 6.21[105] | 56%[3] | 263.8[107][108] | 4,723[110] or 6,323[109] |

| 2010 | 10.17[105] | 56%[3] | 290[107] | 6,256[110] or 7,831[109] |

| 2011 | 13.12[105] | 54%[3] | 370[107] | 9,286[110] |

| 2012 | 17.07[105] | 48.5%[111] | 462[112] | |

| 2013 | 21.77[105] | 59%[113] | 612[112] | 18,195[93] |

| 2014 | 29.6[114] | 55%[114] | 830[114] | 23,600[114] |

| 2015 | 44[115] | 61.6%[115] | 1,260[115] | 31,627[115] |

| 2016 | 45.71[2] | 58.33%[2] | 1,370[4] | 41,179[2] |

| 2017 | 55.9[116] | 53.8%[116] | 1,620[116] | 50,776 |

| 2018 | 60.98[117] | 62.2%[118] | 1720[119] | 60,000[120] |

Film Companies

As of April 2015, the largest Chinese film company by worth was Alibaba Pictures (US$8.77 billion). Other large companies include Huayi Brothers Media (US$7.9 billion), Enlight Media (US$5.98 billion) and Bona Film Group (US$542 million).[121] The biggest distributors by market share in 2014 were: China Film Group (32.8%), Huaxia Film (22.89%), Enlight Pictures (7.75%), Bona Film Group (5.99%), Wanda Media (5.2%), Le Vision Pictures (4.1%), Huayi Brothers (2.26%), United Exhibitor Partners (2%), Heng Ye Film Distribution (1.77%) and Beijing Anshi Yingna Entertainment (1.52%).[3] The biggest cinema chains in 2014 by box office gross were: Wanda Cinema Line (US$676.96 million ), China Film Stellar (393.35 million), Dadi Theater Circuit (378.17 million), Shanghai United Circuit (355.07 million), Guangzhou Jinyi Zhujiang (335.39 million), China Film South Cinema Circuit (318.71 million), Zhejiang Time Cinema (190.53 million), China Film Group Digital Cinema Line (177.42 million), Hengdian Cinema Line (170.15 million) and Beijing New Film Association (163.09 million).[3]

Notable Independent Non-state owned Film Companies

Huayi Brothers: China’s most powerful independent (i.e., non state-owned) entertainment company, Beijing-based Huayi Brothers is a diversified company engaged in film and TV production, distribution, theatrical exhibition, as well as talent management. Notable films include 2004's Kung Fu Hustle, and 2010's Aftershock which had a 91% rating on Rotten Tomatoes.[122]

Beijing Enlight Media: Under CEO Wang Changtian, Enlight Media rarely mis-fires in its production and distribution of feature films. Squarely focused on the action and romance genres, Enlight usually places several films in China’s top 20 grossers, and currently has in release the country’s fourth highest-grossing Chinese language film, The Four. Enlight is also a major player in China’s TV series production and distribution businesses. Under the leadership of its CEO Wang Changtian, the publicly traded, Beijing-based company has achieved a market capitalization of nearly US$1 billion.[123]

See also

Lists

- List of Chinese actors

- List of Chinese actresses

- List of Chinese directors

- List of Chinese films

- List of Chinese film production companies (pre-PRC)

- List of highest-grossing films in China

- List of film production companies by country#China

- List of highest-grossing non-English films

Notes

- Bai She Zhuan (1926) 白蛇传 : Legend of the White Snake[22] Adaptation of Legend of the White Snake

- Lianhua is also sometimes referred to in scholarly literature as the "United Photoplay Service"

- Notably Zhang Yimou served as cinematographer for both films.

References

Citations

- "Princess Iron Fan(HKAFF 2017)". Broadway Cinematheque.

- Zhang Rui (3 January 2017). "China reveals box office toppers for 2016". china.org.cn. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- "China Film Industry Report 2014-2015 (In Brief)" (PDF). english.entgroup.cn. EntGroup Inc. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- Frater, Patrick (31 December 2016). "China Box Office Crawls to 3% Gain in 2016". Variety. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- Ye, Tan, 1948- (2012). Historical dictionary of Chinese cinema. Zhu, Yun, 1979-. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 9780810867796. OCLC 764377427.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Du, Daisy Yan (May 2012). "A Wartime Romance: Princess Iron Fan and the Chinese Connection in Early Japanese Animation," in On the Move: The Trans/national Animated Film in 1940s-1970s China. University of Wisconsin-Madison. pp. 15–60.

- Bai, Siying (2013). Recent Developments in the Chinese Film Censorship System. University of International Business and Economics.

- "Breathtaking Photos From Inside the China Studio Luring Hollywood East". Hollywoodreporter.com. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- "Wanda Unveils Plans for $8 Billion 'Movie Metropolis,' Reveals Details About Film Incentives". The Hollywood Reporter.

- Brzeski, Patrick (20 December 2016). "China Says It Has Passed U.S. as Country With Most Movie Screens". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- Tartaglione, Nancy (15 November 2016). "China Will Overtake U.S. In Number Of Movie Screens This Week: Analyst". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Patrick Brzeski, Clifford Coonan (3 April 2014). "Inside Johnny Depp's 'Transcendence' Trip to China". The Hollywood Reporter.

As China's box office continues to boom – it expanded 30 percent in the first quarter of 2014 and is expected to reach $4.64 billion by year's end – Beijing is replacing London and Tokyo as the most important promotional destination for Hollywood talent.

CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - FlorCruz, Michelle (2 April 2014). "Beijing Becomes A Top Spot On International Hollywood Promotional Tours". International Business Times.

The booming mainland Chinese movie market has focused Hollywood's attention on the Chinese audience and now makes Beijing more important on promo tours than Tokyo and Hong Kong

- Edwards, Russell (15 November 2016). "New law, slowing sales take shine off China's box office". Atimes.com. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- Lin, Lilian. "Making Waves: In Blow to Foreign Films, China Gives 'Mermaid' Three-Month Boost".

- Berry, Chris. "China Before 1949", in The Oxford History of World Cinema, edited by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (1997). Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 409.

- Martin Geiselmann (2006). "Chinese Film History - A Short Introduction" (PDF). The University of Vienna- Sinologie Program. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- David Carter (2010). East Asian Cinema. Kamera Books. ISBN 9781842433805.

- Zhang Yingjin (10 October 2003). "A Centennial Review of Chinese Cinema". University of California-San Diego. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- "A Brief History of Chinese Film". Ohio State University. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- Berry, Chris. "China Before 1949", in The Oxford History of World Cinema, edited by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (1997). Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 409–410.

- "《Legend of the White Snake》(1926)". The Chinese Mirror. Archived from the original on 19 March 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- Yingjin Zhang (2012). "Chapter 24 - Chinese Cinema and Technology". A Companion to Chinese Cinema. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 456. ISBN 978-1444330298.

- Laikwan Pang, Building a New China in Cinema (Rowman and Littlefield Productions, Oxford, 2002)

- Kraicer, Shelly (6 December 2005). "Timeline". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 2 August 2010. Retrieved 8 May 2006.

- Ministry of Culture Staff (2003). "Sole Island Movies". ChinaCulture.org. Archived from the original on 26 August 2006. Retrieved 18 August 2006.

- Baskett, Michael (2008). The Attractive Empire: Transnational Film Culture in Imperial Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3223-0. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- Zhang Yingjin (1 January 2007). "Chinese Cinema - Cai Chusheng". University of California-San Diego. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 25 April 2007.

- "Kunlun Film Company". British Film Institute. 2004. Archived from the original on 22 January 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2007.

- Pickowicz, Paul G. "Chinese Film-making on the Eve of the Communist Revolution", in The Chinese Cinema Book, edited by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward (2011). BFI: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 80–81.

- "Welcome to the Hong Kong Film Awards". 2004. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- Zhang Yingjin, "Introduction" in Cinema and Urban Culture in Shanghai, 1922–1943, ed. Yingjin Zhang (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), p. 8.

- Yau, Esther. "China After the Revolution", in The Oxford History of World Cinema, edited by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (1997). Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 694.

- Ward, Julian. "The Remodelling of a National Cinema: Chinese Films of the Seventeen Years (1949–66)", in The Chinese Cinema Book, edited by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward (2011). BFI: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 88.

- Bordwell and Thompson (2010). Film History: An Introduction (Third ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-07-338613-3.

- Li Xiao (17 January 2004). "Film Industry in China". China.org.cn. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- Braester, Yumi. "The Purloined Lantern: Maoist Semiotics and Public Discourse in Early PRC Film and Drama", p 111, in Witness Against History: Literature, Film, and Public Discourse in Twentieth-Century China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003.

- Bordwell and Thompson (2010). Film History: An Introduction (Third ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 371–372. ISBN 978-0-07-338613-3.

- Ward, Julian. "The Remodelling of a National Cinema: Chinese Films of the Seventeen Years (1949–66)", in The Chinese Cinema Book, edited by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward (2011). BFI: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 90.

- Bordwell and Thompson (2010). Film History: An Introduction (Third ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. p. 373. ISBN 978-0-07-338613-3.

- Yau, Esther. "China After the Revolution", in The Oxford History of World Cinema, edited by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (1997). Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 695.

- Ward, Julian. "The Remodelling of a National Cinema: Chinese Films of the Seventeen Years (1949–66)", in The Chinese Cinema Book, edited by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward (2011). BFI: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 92–93.

- Bordwell and Thompson (2010). Film History: An Introduction (Third ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 372–373. ISBN 978-0-07-338613-3.

- Bordwell and Thompson (2010). Film History: An Introduction (Third ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 370–373. ISBN 978-0-07-338613-3.

- Yau, Esther. "China After the Revolution", in The Oxford History of World Cinema, edited by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (1997). Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 696.

- Zhang, Yingjin & Xiao, Zhiwei. "Breaking with Old Ideas" in Encyclopedia of Chinese Film. Taylor & Francis (1998), p. 101. ISBN 0-415-15168-6.

- Bordwell and Thompson (2010). Film History: An Introduction (Third ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. p. 638. ISBN 978-0-07-338613-3.

- Yau, Esther. "China After the Revolution", in The Oxford history of world cinema edited by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (1997). Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 698.

- Yvonne Ng (19 November 2002). "The Irresistible Rise of Asian Cinema-Tian Zhuangzhuang: A Director of the 21st Century". Kinema. Archived from the original on 16 April 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- Rose, S. "The great fall of China", The Guardian, 2002-08-01. Retrieved on 2007-04-28.

- Bordwell and Thompson (2010). Film History: An Introduction (Third ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 639–640. ISBN 978-0-07-338613-3.

- Bordwell and Thompson (2010). Film History: An Introduction (Third ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 638–640. ISBN 978-0-07-338613-3.

- Ma, Weijun (September 2014). "Chinese Main Melody TV Drama: Hollywoodization and Ideological Persuasion". Television & New Media. 15 (6): 523–537. doi:10.1177/1527476412471436. ISSN 1527-4764. S2CID 144145010.

- Rui Zhang, The Cinema of Feng Xiaogang: Commercialization and Censorship in Chinese Cinema after 1989. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008, p. 35.

- Ruru, L. I. (26 January 2016). Staging China : new theatres in the twenty-first century. Li, Ruru. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire. ISBN 9781137529442. OCLC 936371074.

- Wang, Qian (23 September 2013). "Red songs and the main melody: cultural nationalism and political propaganda in Chinese popular music". Perfect Beat. 13 (2): 127–145. doi:10.1558/prbt.v13.i2.127.

- Yu, Hongmei (2013). "Visual Spectacular, Revolutionary Epic, and Personal Voice: The Narration of History in Chinese Main Melody Films". Modern Chinese Literature and Culture. 25 (2): 166–218. ISSN 1520-9857. JSTOR 43492536.

- Braester, Yomi. "Contemporary Mainstream PRC Cinema" in The Chinese Cinema Book (2011), edited by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward, BFI: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 181.

- Rui Zhang, The Cinema of Feng Xiaogang: Commercialization and Censorship in Chinese Cinema after 1989. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008, p. 38–39.

- Braester, Yomi. "Contemporary Mainstream PRC Cinema" in The Chinese Cinema Book (2011), edited by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward, BFI: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 181–182.

- "Chinese Main Melody Film Wins Over Young Moviegoers | CFI". China Film Insider. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- Stephen Teo (July 2003). ""There Is No Sixth Generation!" Director Li Yang on Blind Shaft and His Place in Chinese Cinema". Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Corliss, Richard (26 March 2001). "Bright Lights". Time. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Deborah Young (4 October 1993). "Review: 'Beijing Zazhong'". Variety. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Pamela Jahn (16 May 2014). "A Touch of Sin: Interview with Jia Zhang-ke". Electric Sheep. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Kahn, Joseph (7 May 2003). "Filming the Dark Side Of Capitalism in China". New York Times. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- Rapfogel, Jared (December 2004). "Minimalism and Maximalism: The 42nd New York Film Festival". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on 13 September 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2007.

- "Chinese director Jia Zhangke competing at Cannes 2018". gbtimes.com. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "From D-Buffs to the D-Generation: Piracy, Cinema, and an Alternative Public Sphere in Urban China". Talari.com. 1 April 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- "100 best Chinese Mainland Films: the countdown". Timeoutbeijing.com. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Reynaud, Berenice (September 2003). "Dancing with Myself,Drifting with My Camera: The Emotional Vagabonds". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- Krich, John (5 March 1998). "China's New Documentaries". The San Francisco Examiner.

- Chu, Yingchu (2007). Chinese Documentaries: From Dogma to Polyphony. Routledge. pp. 91–92.

- Zhang, Yingjin (2010). Cinema, Space, and Polylocality in a Globalizing China. University of Hawai'i Press. p. 134.

- "Icarus Films: Featured Filmmakers". icarusfilms.com. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Chen, Yuanyuan. "Old Or New Art? Rethinking Classical Chinese Animation." Journal of Chinese Cinemas, vol. 11, no. 2, 2017, pp. 175-188.

- Celluloid China: cinematic encounters with culture and society, Harry H. Kuoshu, Southern Illinois University Press (2002), p 202

- 《狼灾记》票房低迷出乎意料 导演的兽性情挑_第一电影网 Archived September 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Louise Edwards, Elaine Jeffreys (2010). Celebrity in China. Hong Kong University Press. p. 456.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "CCTV-电影频道-相聚——《流金岁月》". Cctv.com. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Walsh Megan (20 February 2014). "Feng Xiaogang: the Chinese Spielberg". New Statesman. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Raymond Zhou (29 January 2010). "Confucius loses his way". China Daily. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Yingjin Zhang (ed.) (2012). A Companion to Chinese Cinema. Blackwell Publishing. p. 357.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Karen Chu (17 June 2012). "Feng Xiaogang Unveils Epic 'Remembering 1942' at the Shanghai Film Festival". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- Stephen Cremin (18 May 2013). "So Young enters China's all-time top ten". Film Business Asia. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Frater, Patrick (9 February 2016). "China Has Biggest Ever Day At Box Office". Variety. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- Brzeski, Patrick (19 February 2016). "China Box Office: 'Mermaid' Becomes Top-Grossing Film Ever With $400M". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Papish, Jonathan (29 February 2016). "China Box Office: February and 'The Mermaid' Smash Records". China Film Insider. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- Cremin, Stephen (July 24, 2012). "Resurrection takes China BO record". Film Business Asia. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- "《让子弹飞》票房7.3亿 姜文成国内第一导演_娱乐_腾讯网". Ent.qq.com. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- "Zhou Xun Obtains Hong Kong Citizenship". Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- Brenhouse, Hillary (31 January 2011). "As Its Box Office Booms, Chinese Cinema Makes a 3-D Push". Time. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- Kevin Ma (January 6, 2014). "China B.O. up 27% in 2013". Film Business Asia. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- Stephen Cremin and Patrick Frater (January 3, 2013). "Xu joins one billion club". Film Business Asia. Archived from the original on February 5, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- Stephen Cremin (18 May 2013). "So Young enters China's all-time top ten". Film Business Asia. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- Xu Fan (China Daily) (18 June 2015). "Internet Giants Move From Behind the Camera to Front". english.entgroup.cn. EntGroup Inc. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Kevin Ma (2 January 2015). "China B.O up 36% in 2014". Film Business Asia. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- Kevin Mar (10 December 2013). "China B.O. passes RMB20 billion in 2013". Film Business Asia. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- Patrick Frater (30 September 2015). "IMAX China Sets Cautious IPO Share Price". variety.com. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- Julie Makinen (29 December 2015). "Movie ticket sales jump 48% in China, but Hollywood has reason to worry". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- Patrick Brzeski (31 December 2015). "China Box Office Grows Astonishing 49 Percent in 2015, Hits $6.78 Billion". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Tartaglione, Nancy (1 January 2016). "China Box Office Ends Year With $6.77B; On Way To Overtaking U.S. In 2017?". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Brzeski, Patrick (15 February 2016). "China Box Office Breaks World Record With $548M in One Week". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- Jonathan Landreth (15 October 2010). "Report: China b.o. to overtake Japan in 2015". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- Bai Shi (Beijing Review) (9 February 2014). "Hollywood Takes a Hit". english.entgroup.cn. EntGroup Inc. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- "Domestic films' share of box office in Australia and selected other countries, 2000–2009". screenaustralia.gov.au. Screen Australia. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- "Table 11: Exhibition - Admissions & Gross Box Office (GBO)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- "Top 20 countries by number of cinema admissions, 2005–2010". screenaustralia.gov.au. Screen Australia. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- "Top 20 countries ranked by number of cinema screens, 2005–2010". screenaustralia.gov.au. Screen Australia. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- "Table 8: Cinema Infrastructure - Capacity". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- Patrick Frater (10 January 2013). "China BO exceeds RMB17 billion". Film Business Asia. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- Patrick Frater (17 January 2014). "China Adds 5,000 Cinema Screens in 2013". variety.com. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- "China Box Office: Jackie Chan's 'Police Story 2013' Tops Chart Dominated by Local Fare". The Hollywood Reporter. 7 January 2014.

- Patrick Frater (4 January 2015). "China Surges 36% in Total Box Office Revenue". Variety. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- Variety Staff (31 December 2015). "China Box Office Growth at 49% as Total Hits $6.78 Billion". Variety. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Frater, Patrick (1 January 2018). "China Box Office Expands by $2 Billion to Hit $8.6 Billion in 2017". Variety. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- Shackleton2019-01-02T00:38:00+00:00, Liz. "China's box office increases by 9% to $8.9bn in 2018". Screen. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "China: box office revenue share by region of movie origin 2018". Statista. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "China: number of movie tickets sold 2018". Statista. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "China: cinema screen number 2019". Statista. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Patrick Frater (9 April 2015). "Chinese Media Stocks Stage Major Rally in U.S. and Asian Markets". variety.com. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- "July 2012". chinafilmbiz 中国电影业务. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- "July 2012". chinafilmbiz 中国电影业务. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

Sources

- Bordwell, David; Thompson, Kristin (2010). Film history : an introduction (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 978-0073386133.

- Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey, ed. (1997). The Oxford history of world cinema (Paperback ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198742425.

Further reading

- Rey Chow, Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography, and Contemporary Chinese Cinema, Columbia University Press 1995.

- Cheng, Jim, Annotated Bibliography For Chinese Film Studies, Hong Kong University Press 2004.

- Shuqin Cui, Women Through the Lens: Gender and Nation in a Century of Chinese Cinema, University of Hawaii Press 2003.

- Dai Jinhua, Cinema and Desire: Feminist Marxism and Cultural Politics in the Work of Dai Jinhua, eds. Jing Wang and Tani E. Barlow. London: Verso 2002.

- Rolf Giesen (2015). Chinese Animation: A History and Filmography, 1922-2012. Illustrated by Bryn Barnard. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476615523. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- Hu, Lindan (2017). "Rescuing female desire from revolutionary history: Chinese women's cinema in the 1980s". Asian Journal of Women's Studies. 23 (1): 49–65. doi:10.1080/12259276.2017.1279890. S2CID 218771001.

- Harry H. Kuoshu, Celluloid China: Cinematic Encounters with Culture and Society, Southern Illinois University Press 2002 - introduction, discusses 15 films at length.

- Jay Leyda, Dianying, MIT Press, 1972.

- Laikwan Pang, Building a New China in Cinema: The Chinese Left-Wing Cinema Movement, 1932-1937, Rowman & Littlefield Pub Inc 2002.

- Quiquemelle, Marie-Claire; Passek, Jean-Loup, eds. (1985). Le Cinéma chinois. Paris: Centre national d'art et de culture Georges Pompidou. ISBN 9782858502639. OCLC 11965661.

- Rea, Christopher. 2021. Chinese Film Classics, 1922-1949, Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231188135

- Seio Nakajima. 2016. “The genesis, structure and transformation of the contemporary Chinese cinematic field: Global linkages and national refractions.” Global Media and Communication Volume 12, Number 1, pp 85–108.

- Zhen Ni, Chris Berry, Memoirs From The Beijing Film Academy, Duke University Press 2002.

- Semsel, George, ed. "Chinese Film: The State of the Art in the People's Republic", Praeger, 1987.

- Semsel, George, Xia Hong, and Hou Jianping, eds. Chinese Film Theory: A Guide to the New Era", Praeger, 1990.

- Semsel, George, Chen Xihe, and Xia Hong, eds. Film in Contemporary China: Critical Debates, 1979-1989", Praeger, 1993.

- Gary G. Xu, Sinascape: Contemporary Chinese Cinema, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007.

- Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh and Darrell William Davis. 2008. “Re-nationalizing China’s film industry: case study on the China Film Group and film marketization.” Journal of Chinese Cinemas Volume 2, Issue 1, pp 37–51.

- Yingjin Zhang, Chinese National Cinema (National Cinemas Series.), Routledge 2004 - general introduction.

- Yingjin Zhang (Author), Zhiwei Xiao (Author, Editor), Encyclopedia of Chinese Film, Routledge, 1998.

- Ying Zhu, "Chinese Cinema during the Era of Reform: the Ingenuity of the System", Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003.

- Ying Zhu, "Art, Politics and Commerce in Chinese Cinema", co-edited with Stanley Rosen, Hong Kong University Press, 2010

- Ying Zhu and Seio Nakajima, “The Evolution of Chinese Film as an Industry,” pp. 17–33 in Stanley Rosen and Ying Zhu, eds., Art, Politics and Commerce in Chinese Cinema, Hong Kong University Press, 2010.

- Wang, Lingzhen. Chinese Women's Cinema: Transnational Contexts. Columbia University Press, August 13, 2013. ISBN 0231527446, 9780231527446.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cinema of China. |

- Chinese Film Classics - website on Chinese cinema history, featuring English-subtitled copies of Chinese films made up to 1949

- Chinese Cinema at Curlie

- Journal of Chinese Cinema

- MCLC Resource Center-Media

- The Chinese Mirror — A Journal of Chinese Film History