Yuan (currency)

The yuan (/juːˈɑːn, -æn/; sign: ¥; Chinese: 元; pinyin: yuán; [ɥæ̌n] (![]() listen)) is the base unit of a number of former and present-day currencies in Chinese.

listen)) is the base unit of a number of former and present-day currencies in Chinese.

A yuan (Chinese: 元; pinyin: yuán) is also known colloquially as a kuai (Chinese: 块; pinyin: kuài; lit. 'lump'; originally a lump of silver). One yuan is divided into 10 jiao (Chinese: 角; pinyin: jiǎo; lit. 'corner') or colloquially mao (Chinese: 毛; pinyin: máo "feather"). One jiao is divided into 10 fen (Chinese: 分; pinyin: fēn; lit. 'small portion').

Current usage

Today, the term "Yuan" usually refers to the primary unit of account of the renminbi (RMB), the currency of the People's Republic of China.[1] RMB banknotes start at one Yuan and go up to 100 Yuan. It is also used as a synonym of that currency, especially in international contexts – the ISO 4217 standard code for renminbi is CNY, an abbreviation of "Chinese yuan". (A similar case is the use of the terms sterling to designate British currency and pound for the unit of account.)

The symbol for the yuan (元) is also used in Chinese to refer to the currency units of Japan (yen) and Korea (won), and is used to translate the currency unit dollar as well as some other currencies; for example, the United States dollar is called Meiyuan (Chinese: 美元; pinyin: Měiyuán; lit. 'American yuan') in Chinese, and the euro is called Ouyuan (Chinese: 欧元; pinyin: Ōuyuán; lit. 'European yuan'). When used in English in the context of the modern foreign exchange market, the Chinese yuan (CNY) refers to the renminbi (RMB), which is the official currency used in mainland China.

Etymology, writing and pronunciation

In Standard (Mandarin) Chinese, yuán literally means a "round object" or "round coin". During the Qing Dynasty, the yuan was a round coin made of silver.

In informal contexts, the word is written with the simplified Chinese character 元, that literally means "beginning". In formal contexts it is written with the simplified character 圆 or with the traditional version 圓, both meaning "round", after the shape of the coins.[2] These are all pronounced yuán in modern Standard Chinese, but were originally pronounced differently, and remain distinct in Wu Chinese: 元 = nyoe, 圓 = yoe.

In the People's Republic of China, '¥' or 'RMB' is often prefixed to the amount to indicate that the currency is the renminbi (e.g. ¥100元 or RMB 100元).

Alternative words

In many parts of China, the unit of renminbi is sometimes colloquially called kuài (simplified Chinese: 块; traditional Chinese: 塊, literally "piece") rather than yuán. The pinyin term kuài has also been written as "quay" in English language publications[3]

In Cantonese, widely spoken in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong and Macau, the yuan, jiao, and fen are called mān (Chinese: 蚊), hòuh (Chinese: 毫), and sīn (Chinese: 仙), respectively. Sīn is a loan word from the English cent.

Related currency units

The traditional character 圓 is also used to denote the base unit of Hong Kong dollar, the Macanese pataca, and the New Taiwan dollar. However, they do not share the same names for the subdivisions. The unit of a New Taiwan dollar is also referred to in Standard Chinese as yuán and written as 元, 圆 or 圓.

The names of the Korean and Japanese currency units, won and yen respectively, are cognates of Mandarin yuán, also meaning "round" in the Korean and Japanese languages.

The Japanese yen (en) was originally also written with the kanji (Chinese) character 圓, which was simplified to 円 with the promulgation of the Tōyō kanji in 1946.

The Korean won (won) used to be written with the hanja (Chinese) character 圜 from 1902 to 1910, and 圓 some time after World War II. It is now written as 원 in Hangul exclusively, in both North and South Korea.

Early history

In 1889, the yuan was derived from the Spanish dollar which circulated widely in southeast Asia since the 17th century due to Spanish presence in the region, namely the Philippines and Guam. It was subdivided into 1000 cash (Chinese: 文; pinyin: wén), 100 cents or fen (Chinese: 分; pinyin: fēn), and 10 jiao (Chinese: 角; pinyin: jiǎo, cf. dime). It replaced copper cash and various silver ingots called sycees.[4] The sycees were denominated in tael. The yuan was valued at 0.72 tael, (or 7 mace and 2 candareens).[5]

Banknotes were issued in yuan denominations from the 1890s by several local and private banks, along with the Imperial Bank of China and the "Hu Pu Bank" (later the "Ta-Ch'ing Government Bank"), established by the Imperial government. During the Imperial period, banknotes were issued in denominations of 1, 2 and 5 jiao, 1, 2, 5, 10, 50 and 100 yuan, although notes below 1 yuan were uncommon.

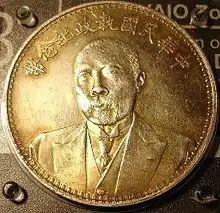

The earliest issues were silver coins produced at the Guangdong mint, known in the West at the time as Canton, and transliterated as Kwangtung, in denominations of 5 cents, 1, 2 and 5 jiao and 1 yuan. Other regional mints were opened in the 1890s producing similar silver coins along with copper coins in denominations of 1, 2, 5, 10 and 20 cash.[5] The central government began issuing its own coins in the yuan currency system in 1903. Banknotes were issued in yuan denominations from the 1890s by several local and private banks, along with banks established by the Imperial government.

The central government began issuing its own coins in the yuan currency system in 1903. These were brass 1 cash, copper 2, 5, 10 and 20 cash, and silver 1, 2 and 5 jiao and 1 yuan. After the revolution, although the designs changed, the sizes and metals used in the coinage remained mostly unchanged until the 1930s. From 1936, the central government issued nickel (later cupronickel) 5, 10 and 20 fen and 1⁄2 yuan coins. Aluminium 1 and 5 fen pieces were issued in 1940.

Date of first "yuan" coins by province

This table sets out the first "silver yuan" coins minted by each province.

| Province | Years of coin production | |

|---|---|---|

| Start | Finish | |

| Anhui (Anhwei) | 1897 | 1909 |

| Zhejiang (Chekiang) | 1897 | 1924 |

| Hebei (Chihli) | 1896 | 1908 |

| Liaoning (Fongtien) | 1897 | 1929 |

| Fujian (Fukien) | 1896 | 1932 |

| Henan (Honan) | 1905 | 1931 |

| Hunan | 1897 | 1926 |

| Hubei (Hupeh) | 1895 | 1920 |

| Gansu (Kansu) | 1914 | 1928 |

| Jiangnan (Kiangnan) | 1898 | 1911 |

| Jiangxi (Kiangsi) | 1901 | 1912 |

| Jiangsu (Kiangsu) | 1898 | 1906 |

| Jilin (Kirin) | 1899 | 1909 |

| Guangxi (Kwangsi) | 1919 | 1949 |

| Guangdong (Kwangtung) | 1889 | 1929 |

| Guizhou (Kweichow) | 1928 | 1949 |

| Shanxi (Shansi) | 1913 | 1913 |

| Shandong (Shantung) | 1904 | 1906 |

| Shaanxi (Shensi) | 1928 | 1928 |

| Xinjiang (Sinkiang) | 1901 | 1949 |

| Sichuan (Szechwan) | 1898 | 1930 |

| Yunnan | 1906 | 1949 |

Republican era

In 1917, the warlord in control of Manchuria, Zhang Zuolin, introduced a new currency, known as the Fengtien yuan or dollar, for use in the Three Eastern Provinces. It was valued at 1.2 yuan in the earlier (and still circulating) "small money" banknotes and was initially set equal to the Japanese yen. It maintained its value (at times being worth a little more than the yen) until 1925, when Zhang Zuolin's military involvement in the rest of China lead to an increase in banknote production and a fall in the currency's value. The currency lost most of its value in 1928 as a consequence of the disturbance following Zhang Zuolin's assassination. The Fengtien yuan was only issued in banknote form, with 1, 5 and 10 yuan notes issued in 1917, followed by 50 and 100 yuan notes in 1924. The last notes were issued in 1928.

The number of banks issuing paper money increased after the revolution. Significant national issuers included the "Commercial Bank of China" (the former Imperial Bank), the "Bank of China" (the former Ta-Ch'ing Government Bank), the "Bank of Communications", the "Ningpo Commercial Bank", the "Central Bank of China" and the "Farmers Bank of China". Of these, only the Central Bank of China issued notes beyond 1943. An exceptionally large number of banknotes were issued during the Republican era (1911–1949) by provincial banks (both Nationalist and Communist).

After the revolution, a great many local, national and foreign banks issued currency. Although the provincial coinages mostly ended in the 1920s, the provincial banks continued issuing notes until 1949, including Communist issues from 1930. Most of the banknotes issued for use throughout the country bore the words "National Currency", as did some of the provincial banks. The remaining provincial banknotes bore the words "Local Currency". These circulated at varying exchange rates to the national currency issues. After the revolution, in addition to the denominations already in circulation, "small money" notes proliferated, with 1, 2 and 5 cent denominations appearing. Many notes were issued denominated in English in cash (wén).

During the 1930s, several new currencies came into being in China due to the activities of the invading Japanese. The pre-existing, national currency yuan came to be associated only with the Nationalist, Kuomintang government. In 1935, the Kuomintang Government enacted currency reforms to limit currency issuance to four major government controlled banks: the Bank of China, Central Bank of China, Bank of Communications and later the Farmers Bank of China. The circulation of silver yuan coins was prohibited and private ownership of silver was banned. The banknotes issued in its place were known as fabi (Chinese: 法幣; pinyin: fǎbì) or "Legal tender". A new series of base metal coins began production in 1936 following the reforms.

The Japanese established two collaborationist regimes during their occupation in China. In the north, the "Provisional Government of the Republic of China" (Chinese: 中華民國臨時政府) based in Peking (Beijing) established the Federal Reserve Bank of China (Chinese: 中國聯合準備銀行; pinyin: Zhōngguó liánhé zhǔnbèi yínháng). The Japanese occupiers issued coins and banknotes denominated in li (Chinese: 釐) (and were worth 1⁄1000 of a yuan), fen, jiao and yuan. Issuers included a variety of banks, including the Central Reserve Bank of China (for the puppet government in Nanking) and the Federal Reserve Bank of China (for the puppet government in Peking (Beijing)). The Japanese decreed the exchange rates between the various banks' issues and those of the Nationalists but the banknotes circulated with varying degrees of acceptance among the Chinese population. Between 1932 and 1945, the puppet state of Manchukuo issued its own yuan.

In the aftermath of the Second World War and during the civil war which followed, Nationalist China suffered from hyperinflation, leading to the introduction of a new currency in 1948, the gold yuan. In the 1940s, larger denominations of notes appeared due to the high inflation. 500 yuan notes were introduced in 1941, followed by 1000 and 2000 yuan in 1942, 2500 and 5000 yuan in 1945 and 10,000 yuan in 1947.

Between 1930 and 1948, banknotes were also issued by the Central Bank of China denominated in customs gold units. These, known as "gold yuan notes", circulated as normal currency in the 1940s alongside the yuan.

Banknotes of the yuan suffered from hyperinflation following the Second World War and were replaced in August 1948 by notes denominated in gold yuan, worth 3 million old yuan. There was no link between the gold yuan and gold metal or coins and this yuan also suffered from hyperinflation.

In 1948, the Central Bank of China issued notes (some dated 1945 and 1946) in denominations of 1, 2 and 5 jiao, 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 yuan. In 1949, higher denominations of 500, 1000, 5000, 10,000, 50,000, 100,000, 500,000, 1,000,000 and 5,000,000 yuan were issued. The Central Bank of China issued notes in denominations of 1 and 5 fen, 1, 2 and 5 jiao, 1, 5 and 10 yuan.

In July 1949, the Nationalist Government introduced the silver yuan, which was initially worth 500 million gold yuan. It circulated for a few months on the mainland before the end of the civil war. This silver yuan remained the de jure official currency of the Republic government in Taiwan until 2000.

Civil War period

The various Soviets under the control of the Communist Party of China issued coins between 1931 and 1935, and banknotes between 1930 and 1949. Some of the banknotes were denominated in chuàn, strings of wén coins. The People's Bank was founded in 1948 and began issuing currency that year, but some of the regional banks continued to issue their own notes in to 1949.

After the defeat of Japan in 1945, the Central Bank of China issued a separate currency in the northeast to replace those issued by the puppet banks—north-eastern yuan (Chinese: 東北九省流通券; pinyin: Dōngběi jiǔ shěng liútōngquàn). It was worth 20 of the yuan which circulated in the rest of the country. It was replaced in 1948 by the gold yuan at a rate of 150,000 north-eastern yuan to 1 gold yuan. In 1945, notes were introduced in denominations of 1, 5, 10, 50 and 100 yuan. 500 yuan notes were added in 1946, followed by 1000 and 2000 yuan in 1947 and 5000 and 10,000 yuan in 1948.

Various, mostly crude, coins were produced by the Soviets. Some only issued silver 1 yuan coins (Hunan, Hubei-Hunan-Anhui (Hupeh-Honan-Anhwei or E-Yu-Wan Soviet Area), Fujian-Zhejiang-Jiangxi (Min-Che-Kan or Min-Zhe-Gan Soviet Area), North Shaanxi (North Shensi or Shanbei Base Area) and Pingjiang (P'ing Chiang Base Area)) whilst the West Hunan-Hubei (Hsiang-O-Hsi or West Xiang-E) Soviet only issued copper 1 fen coins and the North-West Anhui (Wan-Hsi-Pei or North-West Wan) Soviet issued only copper 50 wen coins. The Chinese Soviet Republic issued copper 1 and 5 fen and silver 2 jiao and 1 yuan coins. The Sichuan-Shaanxi (Szechuan-Shensi or Chuan-Shan) Soviet issued copper 200 and 500 wen and silver 1 yuan coins.

Notes were produced by many different banks. There were two phases of note production. The first, up until 1936, involved banks in a total of seven areas, most of which were organized as Soviets. These were:

| Area | Start year | End year | Denominations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese Soviet Republic | 1933 | 1936 | 1 fen |

| 5 fen | |||

| 1 jiao | |||

| 2 jiao | |||

| 5 jiao | |||

| 1 yuan | |||

| 2 yuan | |||

| 3 yuan | |||

| Hunan-Hubei-Jiangxi | 1931 | 1933 | 1 jiao |

| 2 jiao | |||

| 3 jiao | |||

| 5 jiao | |||

| 1 yuan | |||

| Northwest Anwei | 1932 | 2 jiao | |

| 5 jiao | |||

| 1 yuan | |||

| 5 yuan | |||

| Fujian-Zhejiang-Jiangxi | 1932 | 1934 | 10 wén |

| 1 jiao | |||

| 2 jiao | |||

| 5 jiao | |||

| 1 yuan | |||

| 10 yuan | |||

| Hubei | 1930 | 1932 | 1 chuan |

| 2 chuan | |||

| 10 chuan | |||

| 1 chuan | |||

| 2 chuan | |||

| 5 jiao | |||

| 1 yuan | |||

| Pingjiang | 1931 | 1 jiao | |

| 2 jiao | |||

| Sichuan-Shaanxi | 1932 | 1933 | 1 chuan |

| 2 chuan | |||

| 3 chuan | |||

| 5 chuan | |||

| 10 chuan | |||

Today

Production of banknotes by Communist Party forces ceased in 1936 but resumed in 1938 and continued through to the centralization of money production in 1948. A great many regional banks and other entities issued notes. Before 1942, denominations up to 100 yuan were issued. That year, the first notes up to 1000 yuan appeared. Notes up to 5000 yuan appeared in 1943, with 10,000 yuan notes appearing in 1947, 50,000 yuan in 1948 and 100,000 yuan in 1949.

As the People's Liberation Army took control of most of China, they introduced a new currency, in banknote form only, denominated in yuan. This became the sole currency of mainland China at the end of the civil war. A new yuan was introduced in 1955 at a rate of 10,000 old yuan = 1 new yuan, known as the renminbi yuan. It is the currency of the People's Republic of China to this day.

The term yuan is also used in Taiwan. In 1946, a new currency was introduced for circulation there, replacing the Japanese issued Taiwan yen, the Old Taiwan dollar. It was not directly related to the mainland yuan. In 1949, a second yuan was introduced in Taiwan, replacing the first at a rate of 40,000 to 1. Known as the New Taiwan dollar, it remains the currency of Taiwan today.

Connection with dollar

Originally, a silver yuan had the same specifications as a silver Spanish dollar. During the Republican era (1911–1949), the transliteration "yuan" was often printed on the reverse of the first yuan banknotes but sometimes "dollar" was used instead.[6]

In the Republic of China, the common English name is the "New Taiwan dollar" but banknotes issued between 1949 and 1956 used "yuan" as the transliteration.[7] More modern notes lack any transliteration.

See also

| Look up Yuan in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

References

Citations

- Phillips, Matt (2010-01-21). "Yuan or renminbi: what's the right word for China's currency?". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- "Yuan | Define Yuan at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- Randau, Henk R.; Medinskaya, Olga (10 November 2014). Chinese Business 2.0 | Internationalizing the RMB. ISBN 9783319076775. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- "History of the Chinese Yuan". currencyinformation.org. Currency Information and Research. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- Chinese Dragon Coinage Ken Elks, 2000.

- Ronald Wise. "Banknote images of China, 1914–1949". Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- sinobanknote.com. "Table of New Taiwan dollar". Retrieved 2006-11-23.

Bibliography

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Meyerhofer, Adi (2013). 袁大头.Yuan-Shihkai Dollar: 'Fat Man Dollar' Forgeries and Remints (PDF). Munich.

- Pick, Albert (1990). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: Specialized Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (6th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-149-8.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.