Curious George (film)

Curious George is a 2006 animated adventure comedy film based on the book series written by H. A. Rey and Margret Rey and illustrated by Alan J. Shalleck. It was directed by Matthew O'Callaghan, who replaced Jun Falkenstein. Ken Kaufman wrote the screenplay based on a story by him and Mike Werb. Ron Howard, David Kirschner, and Jon Shapiro produced. Featuring the voices of Will Ferrell, Drew Barrymore, David Cross, Eugene Levy, Joan Plowright, and Dick Van Dyke, with Frank Welker voicing the titular character, it was Imagine Entertainment's first fully animated film, as well as Universal Animation Studios' first theatrically released film.

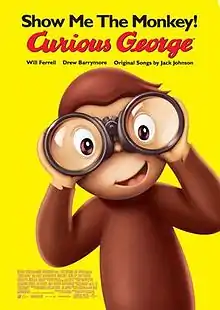

| Curious George | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Matthew O'Callaghan |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | Ken Kaufman |

| Story by |

|

| Based on | |

| Starring | |

| Music by |

|

| Edited by | Julie Rogers |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures[2] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 87 minutes[3] |

| Country | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $50 million[3] |

| Box office | $70 million[3] |

The film had been under development at Imagine Entertainment for a long time, dating back at least 1992, but it is possible that it was conceived years before. Although a traditionally animated film, it blends animation with computer-generated, 3D CGI scenery and objects that take up 20% of its environment. It features a musical score by Heitor Pereira, with songs produced by the musician Jack Johnson.

Curious George was released on February 10, 2006 by Universal Pictures to mainly positive critical reception, and grossed $70 million against a budget of $50 million. It is the only theatrical Curious George film as its four sequels were released as direct-to-video films. A second theatrical Curious George film is in development, with Andrew Adamson set to direct.

Plot

Ted is a tour guide at the Bloomsberry Museum who gives weekly presentations to schoolteacher Maggie Dunlop and her students. The museum's owner, Mr. Bloomsberry, informs Ted that the museum is no longer earning a steady profit and will have to close. Mr. Bloomsberry's son Junior wants to tear down the museum and replace it with a commercial parking lot. Ted impulsively volunteers to travel to Africa to bring back an ancient forty-foot tall idol known as the Lost Shrine of Zagawa, in the hopes that it will attract visitors. He is outfitted with a bright yellow suit and hat and boards a cargo ship to Africa.

In the African jungle, Ted finds the idol with the help of his guide, Edu, but discovers it to be only three inches tall. He sends a photograph of it to the museum, but the photograph's angle leads Mr. Bloomsberry to believe that the idol was even larger than he thought. Ted encounters a happy and mischievous orphaned monkey living in the jungle and gives him his yellow hat. Not wanting to be left alone, the monkey follows him and boards the cargo ship. Ted returns home and finds advertisements for the shrine all over the city.

In Ted's apartment building, the monkey makes his way to the penthouse, owned by Ms. Plushbottom, and covers the walls with paint. Due to the building's strict policy against pets, Ted is evicted by Ivan, the doorman. Ted reveals the idol's actual size to Mr. Bloomsberry and is kicked out of the museum by Junior after the monkey accidentally destroys an Apatosaurus skeleton. After a failed call to the animal control service, Ted and the monkey are forced to sleep outside in a park. The next morning, Ted follows the monkey into the zoo, where Maggie and her students name the monkey George after a nearby statue of George Washington. George floats away on helium balloons that are popped by bird control spikes, but he is saved by Ted.

At the home of Clovis, an inventor, George discovers that an overhead projector can make the idol appear forty feet tall. Ted shows the projector to Mr. Bloomsberry, who sees it as the only way to save the museum and tells Ted that he is proud of him. A jealous Junior pours some of his coffee on the projector and gives the rest to George, blaming him when the projector breaks. With his plan derailed, Ted sadly tells the crowd outside the museum that there is no idol and that the museum will permanently close. Ted has a falling-out with George and orders him to leave, allowing animal control to capture George to be returned to Africa in the process. He subsequently realizes that he misses George.

Ted speaks with Maggie, who helps him understand what is important in life. He regrets his decision to let George be captured and reunites with him on the cargo ship, explaining to George that nothing else matters besides their friendship. George discovers that the idol reveals a pictogram when turned to the light, and Ted realizes that the small idol is a map to the real idol. When their ship reaches Africa, they are able to find the actual forty-foot tall idol.

The enormous idol is finally displayed in the museum, which successfully reopens with new exhibits. Although despondent that he did not get his parking lot, Junior gets a job as the museum's valet and finds joy in his father finally being proud of him. Ivan, who has grown fond of George, invites Ted to move back into his apartment. Ted and Maggie share a romantic moment but are interrupted by George, who has started a rocket; Ted jumps in with him and they end up repeatedly circumnavigating the globe.

Voice cast

- Frank Welker as George, a curious monkey. The film's press notes mentioned that while George would be more accurately described as a chimpanzee, he was referred to as a monkey for tradition and consistency with the book series.[4][5] Welker described the character as "the nicest little monkey you would ever want to meet".[6] Director Matthew O'Callaghan said that it was challenging to effectively convey the monkey's emotions because the character does not speak; because of this, George's original design from the books' illustrations was modified, including replacing his black-dot eyes with larger, more expressive eyes that have irises.[7]

- Will Ferrell as Ted / The Man with the Yellow Hat, a tour guide at the Bloomsberry Museum. In a deleted scene, his last name was revealed to be Shackleford.[8] Ferrell described the character as "a blank canvas" and "a guy who's lived his life in a box".[9] O'Callaghan stated that Ferrell's casting led to an expanded role for the character, in contrast to The Man with the Yellow Hat's relatively limited presence in the book series.[10]

- Drew Barrymore as Maggie Dunlop, an elementary school teacher. The character was named after Margret Rey, who created the Curious George series with her husband, H. A. Rey.[9] O'Callaghan favored Barrymore for the role, saying: "I've always been a big fan of Drew Barrymore so I suggested her to the studio and they all loved the idea of her."[11]

- David Cross as Junior, the son of the museum's owner. An early version of the screenplay involved several antagonists; O'Callaghan and screenwriter Ken Kaufman eventually replaced the multiple characters with Junior in order to simplify the story.[7]

- Eugene Levy as Clovis, an inventor who builds robotic animals. Levy has said that his experience with the character (his first voice role) informed his approach to subsequent voice work; although he prepared extensively with the script, he found that he had to do "just about everything 10 or 15 different ways until they get what it is they're actually looking for", and remarked that the recording process "is a really interesting way to work".[12]

- Joan Plowright as Ms. Plushbottom, Ted's wealthy neighbor.

- Dick Van Dyke as Mr. Bloomsberry, the owner of the Bloomsberry Museum. O'Callaghan said he was surprised that Van Dyke had never done voice work before, explaining that "as an animation director you always want to use people who are fresh, who haven't done animated voices—at least I do. So it was really exciting to get [Van Dyke] in the room and work with him."[11]

Production

Development

Producers Jon Shapiro and David Kirschner contacted Margret Rey in 1990 about the possibility of producing a film based on the classic children's stories that she wrote with her husband, H. A. Rey. Shapiro recalled: "I promised I would be responsible to her and the character for finding others like myself who wanted to make the best version of Curious George possible."[10] Rey agreed and Imagine Entertainment secured the film rights for Curious George in June 1990, with plans to produce a live action film jointly with Hanna-Barbera Productions.[13]

Universal Pictures acquired the merchandising rights to Curious George from publisher Houghton Mifflin in September 1997, after Margret Rey's death the previous year.[14][15] Larry Guterman signed on to direct in 1998 and worked closely with Imagine Entertainment co-chairman Ron Howard to develop the film.[16] However, Guterman left the project reportedly after budget concerns about the film's special effects led Universal and Imagine to postpone production.[17][18] In January 1999, Universal stated that the project continued to be "in active development".[10]

Universal and Imagine were reported to be finalizing a deal with Brad Bird to direct a Curious George film that combined live action and computer-generated imagery (CGI) in October 1999.[18] In July 2001, the newly-merged Vivendi Universal announced that it had acquired Houghton Mifflin, with plans to make Curious George the company's new mascot, coincident with the film's development and release (Houghton Mifflin would be sold the following year due to Vivendi's mounting financial pressures).[19] Bird left the project after the studios decided to shift the film to all-CGI, and in December 2001, it was reported that Universal was in negotiations with David Silverman to direct the film.[20][21] In September 2003, it was announced that Jun Falkenstein signed on to direct the screenplay.[22] According to David Brewster (an animation supervisor for the film), Falkenstein was later fired by the studio and replaced by Matthew O'Callaghan in August 2004.[10]

Writing

According to Stacey Snider, then-chairman of Universal Pictures, it was challenging to turn the relatively simple Curious George books into a full-length film with substantial character development.[10] During the film's production process, many screenwriters wrote potential scripts for the project, including Joe Stillman, Dan Gerson, Babaloo Mandel, Lowell Ganz, Mike Werb, Brian Levant, and Audrey Wells.[7][10][18] Kirschner said that screenwriter Pat Proft wrote a live action draft of the film "that had a lot of really funny, funny stuff, but in the end, what we really wanted was the special relationship between this man and this little monkey... it was really difficult to capture the innocence of that."[10] Brewster recalled that earlier versions of the script by Brad Bird and William Goldman were darker in tone and more adult.[10][23]

When O'Callaghan signed on to direct, replacing Falkenstein, he and screenwriter Ken Kaufman rewrote the story, saying: "We sat in a room for a couple of weeks, we sort of took some elements from the existing structure and created new characters, simplified things, put our heads together and came up with what ultimately was the story of the film." They expanded the role of The Man in the Yellow Hat and gave him a name, making the script more like a buddy film rather than one that was focused primarily on George.[7] The final script contained scenes inspired by many of the earlier books, including Curious George, Curious George Takes a Job, and Curious George Flies a Kite.[7][10]

Animation

When Imagine Entertainment obtained the rights to Curious George in 1990, a live action feature was planned; by 1999, Brad Bird was in talks to direct the film as a combination of live action and CG.[10] The success of Shrek in 2001 led Imagine co-chairman Brian Grazer to shift the film towards all-CG, saying at the time: "George the monkey has to have power and be able to express power, and it's difficult to do that in a live-action mix."[24] Eventually, a final decision was made to use traditional 2D animation for the film to recreate the look and feel of the Curious George books.[7][25] According to executive producer Ken Tsumura, CGI animation was used to create the environments for 20 percent of the film, including the city scenes, in order to allow objects to move in 3D space.[7]

A strict production schedule resulted in all animation work having to be completed within 18 months; Tsumura oversaw the outsourcing of the animation to studios around the world, including studios in the United States, Canada, France, Taiwan, and South Korea. The proportions of George and Ted were kept consistent with the books' illustrations, but their character designs were updated to accommodate the big screen, with O'Callaghan noting that "we had to give them eyes, pupils, teeth, whatever so Ted could enunciate dialog or to create strong expressions with George."[7] CG supervisor Thanh John Nguyen states that they tried to duplicate the look of the cars in the book, which Tsumura describes as bearing the look of the 1940s and 1950s; according to production designer Yarrow Cheney, the filmmakers also partnered with Volkswagen to design the red car that Ted drives, simplifying the design and rounding the edges.[26]

Music

—Kathy Nelson, president of film music at Universal[10]

The film's instrumental score was composed by Heitor Pereira, who replaced Klaus Badelt.[27][28] Hans Zimmer served as the film's executive score producer.[29]

Jack Johnson was hired to write and perform the songs in the film. Johnson said that he was originally asked to write two songs for Curious George, but his enthusiasm for the film led him to write more.[30] He worked closely with the animation team and described a back-and-forth process in which he would provide a sketch of a song in response to a preliminary drawing of a scene, then followed by more detailed animations and lyrics.[31] Describing the songwriting process, Johnson recalled: "The balance was writing lyrics that didn't match things too perfectly, but would kind of reference what was going on in the film. I tried to make metaphors that describe the scene better than trying to exactly match what was going on."[30] Johnson said that many of the film's songs were written for or inspired by his eldest son.[32]

Release

The world premiere of Curious George took place on January 28, 2006 at the ArcLight Hollywood in Los Angeles, California.[33] The film was released to 2,566 theaters on February 10, 2006, and opened at #3 with a total opening weekend gross of $14.7 million averaging $5,730 per theater. The film grossed $58.4 million in the United States and $11.5 million overseas, totaling $69.8 million worldwide.[3] The film was released in the United Kingdom on May 26, 2006, and opened on #5.[34]

Home media

The film was released on DVD on September 26, 2006 by Universal Studios Home Entertainment.[35] It was then released on Blu-ray on March 3, 2015.[36]

Reception

On the review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, Curious George has a 70% approval rating based on 107 reviews, with an average rating of 6.13/10. The website's consensus reads: "Curious George is a bright, sweet, faithful adaptation of the beloved children's books."[37] On Metacritic, the film has an average score of 62 out of 100 based on reviews from 28 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[38] Audiences polled by CinemaScore during opening weekend gave the film an average grade of "A-" on an A+ to F scale.[39] Reviews frequently praised the film's light-hearted tone and its traditional animation style, though some criticized the plot and modern references.[37]

In The New York Times, Dana Stevens called the film "an unexpected delight", praising its "top-drawer voice talent" and "old-fashioned two-dimensional animation that echoes the simple colors and shapes of the books".[40] The Austin Chronicle's Marrit Ingman wrote positively of the film's "sweet, simple message" that "children see the world differently and have much to teach the people who love them."[41] Christy Lemire of the Associated Press praised George's character design, writing that "with his big eyes and bright smile and perpetually sunny disposition, he's pretty much impossible to resist."[42] Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars, noting that it remained "faithful to the spirit and innocence of the books" and writing that the visual style was "uncluttered, charming, and not so realistic that it undermines the fantasies on the screen". Ebert wrote that while he did not particularly enjoy the film himself, he nevertheless gave the film a "thumbs up" on his Ebert & Roeper show because he felt that it would be enjoyable for young children.[43]

Richard Roeper, Ebert's co-host, criticized the film for similar reasons and said that he could not "tell people my age, or someone twenty-five [years old], that they should see nine or ten bucks to see this movie".[37] Brian Lowry of Variety felt that the plot as too simplistic, writing that the film consisted primarily of "various chases through the city" and was "rudimentary on every level".[44] On the other hand, Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune wrote that the film was "overplotted and misfocused" and that "the script's jokes are tougher to find than the shrine", though he praised the film for staying "relatively faithful to the style of the original and delightful H. A. Rey illustrations".[45] Jan Stuart of Newsday criticized the film's modern references in the film, including cell phones and lattes, writing that they resulted in "modernization traps that the makers of the very respectable Winnie the Pooh films managed to avoid".[37] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly also negatively noted the anachronisms in the film, such as the use of caller ID.[46]

The song "Upside Down" by Jack Johnson received a Satellite Award nomination for Best Original Song.[47]

Soundtrack

Sing-A-Longs and Lullabies for the Film Curious George is the soundtrack to the film, featuring songs by Jack Johnson and others. In its first week on Billboard 200 albums chart, the soundtrack made it to the #1 spot, making it Jack Johnson's first number one album (In Between Dreams peaked at two, On and On peaked at three) and making it the first soundtrack to reach number one since the Bad Boys II soundtrack in August 2003 and the first soundtrack to an animated film to top the Billboard 200 since the Pocahontas soundtrack reigned for one week in July 1995.

Television series

The PBS Kids animated television series, also called Curious George, was developed concurrent to the feature film. It also stars Frank Welker reprising as the voice of Curious George and with William H. Macy (later Rino Romano) narrating.[48]

Sequels

A sneak peek for the sequel, Curious George 2: Follow That Monkey! was included in the special features for The Tale of Despereaux. The sequel was released on March 2, 2010. The plot for the sequel centers around George becoming friends with a young elephant named Kayla. George tries to help Kayla travel across the country to be reunited with her family. A second sequel, Curious George 3: Back to the Jungle was released on June 23, 2015. A third sequel, Curious George: Royal Monkey, serving as the fourth film of the series, was released on DVD on September 10, 2019. On September 3, 2020, it was announced that a fourth sequel titled Curious George: Go West, Go Wild would premiere on September 8, 2020 on Peacock.[49] It will also be released on DVD and digital on December 15, 2020.[50] Welker is the only voice actor from the original film to return for the sequels.

References

- "Curious George (2006) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- "Curious George". American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- "Curious George (2006)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- Muller, Bill (February 10, 2006). "Yellow hats off to 'George'". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Blank, Ed (February 10, 2006). "Curious George". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- White, Cindy (September 16, 2009). "Frank Welker Q&A". IGN. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- Strike, Joe (February 10, 2006). "'Curious' & Curiouser". Animation World Network. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- English, Jason (June 13, 2010). "Real names of 23 fictional characters". Mental Floss. CNN. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ""Curious George"—His history and the making of the 2006 motion picture". Christian Spotlight. Films for Christ. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- Welkos, Robert (February 5, 2006). "Real monkeying around". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- Murray, Rebecca (January 29, 2006). "Director Matthew O'Callaghan Talks About the Family Movie "Curious George"". About.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- "'Astro Boy' star Levy says animated projects take him to new places as actor". The Canadian Press. CP24. October 20, 2009. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- Broeske, Pat (June 10, 1990). "Monkey Business". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- Beckstrom, Maja (May 5, 2007). "Curious George comes to town". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- Connor 2015, p. 259.

- "Cats & Dogs". Entertainment Weekly. May 18, 2001. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- Cox, Dan; Petrikin, Chris (January 7, 1999). "By 'George,' U may drop it". Variety. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- Petrikin, Chris (October 31, 1999). "U, Imagine in 'Curious' monkey biz with Bird". Variety. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- Connor 2015, p. 259-261.

- Simon, Brent (October 25, 2006). "Curious George". IGN. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- Linder, Brian (December 13, 2001). "From Monsters, Inc. to Curious George". IGN. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- DeMott, Rick (September 29, 2003). "Curious George Gains Director & Star". Animation World Network. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- Ebert, Roger (February 21, 2006). "This 'George' is for kids". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- Linder, Brian (July 31, 2001). "Grazer Curious About CG George". IGN. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- Ball, Ryan (February 10, 2006). "Moviegoers Get Curious". Animation Magazine. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- Curious George. Bonus Features: A Very Curious Car (DVD)

|format=requires|url=(help). Universal Studios Home Entertainment. 2006. - Winder, Dowlatabadi & Miller-Zarneke 2019, p. 274.

- Armstrong, Josh (April 29, 2004). "Composers lined up for animated projects". Animated Views. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- Donahue, Ann (May 7, 2010). "Musician Jack Johnson plays by his own rules". Reuters. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- Spilberg, Jack (January 23, 2006). "Jack Johnson: Talking 'Curious George' (Interview)". Glide Magazine. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- Locey, Bill (May 1, 2005). "Jack Johnson's Endless Summer". American Songwriter. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- Low, Shereen (December 15, 2008). "Jack Johnson Interview". WestJet Magazine. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- "Celebrity Circuit". CBS News. February 2, 2006. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- "Weekend box office 26th May 2006 - 28th May 2006". www.25thframe.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- https://www.amazon.com/Curious-George-Widescreen-Will-Ferrell/dp/B000GIXEWC/

- https://www.amazon.com/Curious-George-Blu-ray-Will-Ferrell/dp/B00QTG2KQQ/

- "Curious George (2006)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- "Curious George". Metacritic. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "Cinemascore". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on May 24, 2019.

- Stevens, Dana (February 10, 2006). "A Cartoon Monkey With No Aspirations to Cultural Commentary". The New York Times. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- Ingman, Marrit (February 10, 2006). "Curious George". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Lemire, Christy (February 9, 2006). "'Curious George' succeeds by staying true to its roots and keeping it simple". The Everett Herald. Associated Press. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Ebert, Roger (February 9, 2006). "Lots for kids to love about 'George'". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- Lowry, Brian (February 4, 2006). "Curious George". Variety. Reed Business. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- Phillips, Michael (February 10, 2006). "'Curious George'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Gleiberman, Owen (August 8, 2007). "Curious George". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- "2006". Satellite Awards. International Press Academy. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- "Curious George In Production for PBS KIDS". PBS Press Release. January 14, 2005. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- "Video: "Curious George 5: Go West Go Wild" - First Look". The Futon Critic. September 3, 2020.

- https://www.amazon.com/Curious-George-Go-West-Wild/dp/B08J5HP519

Bibliography

- Connor, J. D. (2015). "That Oceanic Feeling". The Studios after the Studios: Neoclassical Hollywood (1970-2010). Stanford University Press. pp. 247–282. ISBN 978-0-8047-9077-2.

- Winder, Catherine; Dowlatabadi, Zahra; Miller-Zarneke, Tracey (2019). "Post-production". Producing Animation (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 265–288. ISBN 978-0-4294-9052-1.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Curious George (film) |

- Official website [Archived December 30, 2006]

- Curious George at IMDb

- Curious George at AllMovie

- Curious George at the TCM Movie Database

- Curious George at The Big Cartoon DataBase

- Curious George at Box Office Mojo

- Curious George at Rotten Tomatoes

- Curious George at Metacritic