Dick Van Dyke

Richard Wayne Van Dyke (born December 13, 1925) is an American actor, comedian, writer, singer, and dancer, whose award-winning career has spanned seven decades.

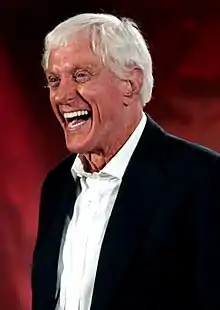

Dick Van Dyke | |

|---|---|

Van Dyke at the 2017 Phoenix Comicon | |

| Born | Richard Wayne Van Dyke December 13, 1925 West Plains, Missouri, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actor, comedian, writer, singer, dancer |

| Years active | 1947–present |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Partner(s) | Michelle Triola Marvin (1976–2009; her death) |

| Children | 4, including Barry |

| Relatives |

|

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1943–1946 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | Armed Forces Radio Service |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | |

Van Dyke first gained recognition on radio and Broadway, then became known for his role as Rob Petrie on the CBS television sitcom The Dick Van Dyke Show, which ran from 1961 to 1966. He also gained significant popularity for roles in the musical films Bye Bye Birdie (1963), Mary Poppins (1964), and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968). His other prominent film appearances include roles in The Comic (1969), Dick Tracy (1990), Curious George (2006), Night at the Museum (2006), Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014), and Mary Poppins Returns (2018). Other prominent TV roles include the leads in The New Dick Van Dyke Show (1971–74), Diagnosis: Murder (1993–2001), and Murder 101 (2006–08) which both co-starred his son Barry.

Van Dyke is the recipient of five Primetime Emmys, a Tony, and a Grammy Award, and was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame in 1995.[1] He received the Screen Actors Guild's highest honor, the SAG Life Achievement Award, in 2013.[2] He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 7021 Hollywood Boulevard and has also been recognized as a Disney Legend.[3]

Early life

Van Dyke was born on December 13, 1925, in West Plains, Missouri,[4] to Hazel Victoria (née McCord; 1896–1992), a stenographer, and Loren Wayne "Cookie" Van Dyke (1898–1976), a salesman.[5][6][7] He grew up in Danville, Illinois. He is the older brother of actor Jerry Van Dyke (1931–2018), who sometimes appeared as his brother in The Dick Van Dyke Show but is best known for a role in the TV series Coach. Van Dyke is a Dutch surname, although he has English, Irish, and Scottish ancestry as well.[8] His family line traces back to Mayflower passenger John Alden.[9]

Among Van Dyke's high school classmates in Danville were Donald O'Connor and Bobby Short, both of whom would go on to successful careers as entertainers.[10] One of his closest friends was a cousin of Gene Hackman, the future actor, who also lived in Danville in those years.[10] Van Dyke's mother's family was very religious, and for a brief period in his youth, he considered a career in ministry, although a drama class in high school convinced him that his true calling was as a professional entertainer.[10] In his autobiography, he wrote, "I suppose that I never completely gave up my childhood idea of being a minister. Only the medium and the message changed. I have still endeavored to touch people's souls, to raise their spirits and put smiles on their faces."[10] Even after the launch of his career as an entertainer, he taught Sunday school in the Presbyterian Church, where he was an elder, and he continued to read such theologians as Martin Buber, Paul Tillich, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who helped explain in practical terms the relevance of religion in everyday life.[10]

World War II

Van Dyke left high school in 1944, his senior year, intending to join the United States Army Air Forces for pilot training during World War II. Denied enlistment several times for being underweight, he was eventually accepted for service as a radio announcer before transferring to the Special Services and entertaining troops in the continental United States.[11] He received his high school diploma in 2004 at age 78.[12]

Career

Radio and stage

During the late 1940s, Van Dyke was a radio DJ in Danville, Illinois. In 1947, Van Dyke was persuaded by pantomime performer Phil Erickson[13] to form a comedy duo with him called "Eric and Van—the Merry Mutes."[14] The team toured the West Coast nightclub circuit, performing a mime act and lip synching to old 78 records. They brought their act to Atlanta, Georgia, in the early 1950s and performed a local television show featuring original skits and music called "The Merry Mutes".[15]

In November 1959, Van Dyke made his Broadway debut in The Girls Against the Boys. He then played the lead role of Albert Peterson in Bye Bye Birdie, which ran from April 14, 1960, to October 7, 1961. In a May 2011 interview with Rachael Ray, Van Dyke said that when he auditioned for a smaller part in the show he had no experience as a dancer, and that after he sang his audition song he did an impromptu soft-shoe out of sheer nervousness. Gower Champion, the show's director and choreographer, was watching, and promptly went up on stage to inform Van Dyke he had the lead. An astonished Van Dyke protested that he could not dance, to which Champion replied: "We'll teach you". That musical won four Tony awards including Van Dyke's Best Featured Actor Tony, in 1961.[16] In 1980, Van Dyke appeared in the title role in the first Broadway revival of The Music Man.[17]

Television

Van Dyke's start in television was with WDSU-TV New Orleans Channel 6 (NBC), first as a single comedian and later as emcee of a comedy program.[18][19][20] Van Dyke's first network TV appearance was with Dennis James on James' Chance of a Lifetime in 1954. He later appeared in two episodes of The Phil Silvers Show during its 1957–58 season. He also appeared early in his career on ABC's The Pat Boone Chevy Showroom and NBC's The Polly Bergen Show. During this time a friend from the Army was working as an executive for CBS television and recommended Van Dyke to that network. Out of this came a seven-year contract with the network.[21] During an interview on NPR's Wait Wait... Don't Tell Me! program, Van Dyke said he was the anchorman for the CBS morning show during this period with Walter Cronkite as his newsman.[8]

From 1961 to 1966, Van Dyke starred in the CBS sitcom The Dick Van Dyke Show, in which he portrayed a comedy writer named Rob Petrie. Originally the show was supposed to have Carl Reiner as the lead but CBS insisted on recasting and Reiner chose Van Dyke to replace him in the role.[21] Complementing Van Dyke was a veteran cast of comic actors including Rose Marie, Morey Amsterdam, Jerry Paris, Ann Morgan Guilbert, Richard Deacon, and Carl Reiner (as Alan Brady), as well as 23-year-old Mary Tyler Moore, who played Rob's wife Laura Petrie. Van Dyke won three Emmy Awards as Outstanding Lead Actor in a Comedy Series, and the series received four Emmy Awards as Outstanding Comedy Series.[22] From 1971 to 1974, Van Dyke starred in an unrelated sitcom called The New Dick Van Dyke Show in which he portrayed a local television talk show host. Although the series was developed by Carl Reiner and starred Hope Lange as his wife, and he received a Golden Globe nomination for his performance, the show was less successful than its predecessor,[23] and Van Dyke pulled the plug on the show after just three seasons.[24] In 1973, Van Dyke voiced his animated likeness for the October 27, 1973 installment of Hanna-Barbera's The New Scooby-Doo Movies, "Scooby-Doo Meets Dick Van Dyke," the series' final first-run episode. The following year, he received an Emmy Award nomination for his role as an alcoholic businessman in the television movie The Morning After (1974). Van Dyke revealed after its release that he had recently overcome a real-life drinking problem. He admits he was an alcoholic for 25 years.[25] That same year he guest-starred as a murderous photographer on an episode of Columbo, Negative Reaction. Van Dyke returned to comedy in 1976 with the sketch comedy show Van Dyke and Company, which Andy Kaufman made his prime time debut.[26][27] Despite being canceled after three months, the show won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Comedy-Variety Series.[28] After a few guest appearances on the long-running comedy-variety series The Carol Burnett Show, Van Dyke became a regular on the show, in the fall of 1977. However, he only appeared in half of the episodes of the final season. For the next decade he appeared mostly in TV movies. One atypical role was as a murdering judge on the second episode of the TV series Matlock in 1986 starring Andy Griffith. In 1987, he guest-starred in an episode of Airwolf, with his son Barry Van Dyke, who was the lead star of the show's fourth and final season on USA Network. In 1989, he guest-starred on the NBC comedy series The Golden Girls portraying a lover of Beatrice Arthur's character. This role earned him his first Emmy Award nomination since 1977.[29]

His film work affected his TV career: the reviews he received for his role as D.A. Fletcher in Dick Tracy led him to star as the character Dr. Mark Sloan first in an episode of Jake and the Fatman, then in a series of TV movies on CBS that became the foundation for his popular television drama Diagnosis: Murder. The series ran from 1993 to 2001 with son Barry Van Dyke co-starring in the role of Dr. Sloan's son Lieutenant Detective Steve Sloan. Also starring on the same show was daytime soap actress Victoria Rowell as Dr. Sloan's pathologist/medical partner, Dr. Amanda Bentley, and Charlie Schlatter in the role of Dr. Sloan's student, Dr. Jesse Travis.[30] Van Dyke continued to find television work after the show ended, including a dramatically and critically successful performance of The Gin Game, produced for television in 2003 that reunited him with Mary Tyler Moore. In 2003, he portrayed a doctor on Scrubs. A 2004 special of The Dick Van Dyke Show titled The Dick Van Dyke Show Revisited was heavily promoted as the first new episode of the classic series to be shown in 38 years. Van Dyke and his surviving cast members recreated their roles; although nominated for a Primetime Emmy,[31][32] the program was roundly panned by critics. In 2006 he guest-starred as college professor Dr. Jonathan Maxwell for a series of Murder 101 mystery films on the Hallmark Channel.

For the Marvel Cinematic Universe television series, WandaVision, Van Dyke was consulted by the producers on how to emulate The Dick Van Dyke Show.[33]

Film

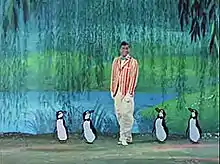

Van Dyke began his film career by playing the role of Albert J. Peterson in the film version of Bye Bye Birdie (1963). Despite his unhappiness with the adaptation—its focus differed from the stage version in that the story now centered on a previously supporting character[34]—the film was a success. That same year, Van Dyke was cast in two roles: as the chimney sweep Bert, and as bank chairman Mr. Dawes Senior, in Walt Disney's Mary Poppins (1964). For his scenes as the chairman, he was heavily costumed to look much older and was credited in that role as "Navckid Keyd" (at the end of the credits, the letters unscramble into "Dick Van Dyke"). Van Dyke's attempt at a cockney accent has been lambasted as one of the worst accents in film history, cited by actors since as an example of how not to sound. In a 2003 poll by Empire magazine of the worst-ever accents in film, he came in second (to Sean Connery in The Untouchables, despite Connery winning an Academy Award for that performance).[35][36] According to Van Dyke, his accent coach was Irish, who "didn't do an accent any better than I did", and that no one alerted him to how bad it was during the production.[37][38][39] Still, Mary Poppins was successful on release and its appeal has endured. "Chim Chim Cher-ee", one of the songs that Van Dyke performed in Mary Poppins, won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for the Sherman Brothers, the film's songwriting duo.

Many of the comedy films Van Dyke starred in throughout the 1960s were relatively unsuccessful at the box office, including What a Way to Go! with Shirley MacLaine, Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N., Fitzwilly, The Art of Love with James Garner and Elke Sommer, Some Kind of a Nut, Never a Dull Moment with Edward G. Robinson, and Divorce American Style with Debbie Reynolds and Jean Simmons. But he also starred as Caractacus Pott (with his native accent, at his own insistence, despite the English setting) in the successful musical version of Ian Fleming's Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968), which co-starred Sally Ann Howes and featured the same songwriters (The Sherman Brothers) and choreographers (Marc Breaux and Dee Dee Wood) as Mary Poppins.

In 1969, Van Dyke appeared in the comedy-drama The Comic, written and directed by Carl Reiner. Van Dyke portrayed a self-destructive silent film era comedian who struggles with alcoholism, depression, and his own rampant ego. Reiner wrote the film especially for Van Dyke, who often spoke of his admiration for silent film era comedians such as Charlie Chaplin and his hero Stan Laurel.[40] Also in 1969, Van Dyke played Rev. Clayton Brooks, a small-town minister who leads his Iowa town to quit smoking for 30 days to win $25 million (equal to $174,296,733 today) from a tobacco company in "Cold Turkey", although that film was not released until 1971.

On Larry King Live, Van Dyke mentioned he turned down the lead role in The Omen which was played by Gregory Peck. He also mentioned his dream role would have been the scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz. Twenty-one years later in 1990, Van Dyke, whose usual role had been the amiable hero, took a small but villainous turn as the crooked DA Fletcher in Warren Beatty's film Dick Tracy. Van Dyke returned to motion pictures in 2006 with Curious George as Mr. Bloomsberry and as villain Cecil Fredericks in the Ben Stiller film Night at the Museum.[41] He reprised the role in a cameo for the sequel, Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009), but it was cut from the film. It can be found in the special features on the DVD release. He also played the character again in the third film, Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014).

In 2018, Van Dyke portrayed Mr. Dawes Jr. in Mary Poppins Returns. He had previously portrayed both Bert and Mr. Dawes, Sr. (Mr. Dawes, Jr.'s late father), in the original film.[42]

Other projects

Van Dyke received a Grammy Award in 1964, along with Julie Andrews, for his performance on the soundtrack to Mary Poppins.[43] In 1970, he published Faith, Hope and Hilarity: A Child's Eye View of Religion a book of humorous anecdotes based largely on his experiences as a Sunday School teacher.[44] Van Dyke was principal in "KXIV Inc." and owned 1400 AM KXIV in Phoenix from 1965 to 1982.[45][46]

As an a cappella enthusiast, he has sung in a group called "Dick Van Dyke and The Vantastix" since September 2000. The quartet has performed several times in Los Angeles as well as on Larry King Live, The First Annual TV Land Awards, and sang the national anthem at three Los Angeles Lakers games including a nationally televised NBA Finals performance on NBC. Van Dyke was made an honorary member of the Barbershop Harmony Society in 1999.[47]

Van Dyke became a computer animation enthusiast after purchasing a Commodore Amiga in 1991. He is credited with the creation of 3D-rendered effects used on Diagnosis: Murder and The Dick Van Dyke Show Revisited. Van Dyke has displayed his computer-generated imagery work at SIGGRAPH, and continues to work with LightWave 3D.[48][49][50]

In 2010, Van Dyke appeared on a children's album titled Rhythm Train, with Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer Chad Smith and singer Leslie Bixler. Van Dyke raps on one of the album's tracks.[51]

In 2017, Van Dyke released his first solo album since 1963's Songs I Like. The album, Step (Back) In Time, was produced by Bill Bixler (who also played sax), with arrangements by Dave Enos (who also played bass) and features noted musicians John Ferraro (Drums), Tony Guerrero (Trumpet & Vocal duet), Mark LeBrun (Piano), Charley Pollard (Trombone) and Leslie Bixler (Vocals). Step (Back) In Time was released by BixMix Records and showcases Van Dyke in a jazz and big band setting on classic songs from the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s.

Van Dyke recorded a duet single for Christmas 2017 with actress Jane Lynch. The song, "We're Going Caroling," was written and produced by Tony Guerrero for Lynch's KitschTone Records label as a digital-only release.

Personal life

On February 12, 1948, while appearing at the Chapman Park Hotel on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, he and the former Margerie Willett were married on the radio show Bride and Groom.[21] They had four children: Christian, Barry, Stacy, and Carrie Beth.[52] They divorced in 1984 after a long separation.

Van Dyke lived with longtime companion Michelle Triola Marvin for more than 30 years, until her death in 2009.[53][54]

Van Dyke is sober and struggled with alcoholism in his past, and checked into a hospital for three weeks in 1972 to be treated for his addiction.[55]

He incorporated his children and grandchildren into his TV endeavors. Son Barry Van Dyke, grandsons Shane Van Dyke and Carey Van Dyke along with other Van Dyke grandchildren and relatives appeared in various episodes of the long-running series Diagnosis: Murder. Although Stacy Van Dyke was not well known in show business, she made an appearance in the Diagnosis: Murder Christmas episode "Murder in the Family" (season 4) as Carol Sloan Hilton, the estranged daughter of Dr. Mark Sloan.

All of Van Dyke's children are married, and he has seven grandchildren. His son Chris was district attorney for Marion County, Oregon, in the 1980s.[56] In 1987, Van Dyke's granddaughter Jessica Van Dyke died from Reye syndrome,[57] which led him to do a series of commercials to raise public awareness of the danger of aspirin to children.

On February 29, 2012, at the age of 86, Van Dyke married 40-year-old make-up artist Arlene Silver. They had met six years earlier at the SAG awards.[58]

Van Dyke was a heavy smoker for most of his adult life. In a January 2013 interview with the London Daily Telegraph, he said he had been using Nicorette gum for the past decade.[59]

In April 2013, Van Dyke revealed that for seven years he had been experiencing symptoms of a neurological disorder, in which he felt a pounding in his head whenever he lay down, but despite his undergoing tests, no diagnosis had been made.[60] He had to cancel scheduled appearances due to fatigue from lack of sleep because of the medical condition.[61] In May 2013, he tweeted that it seemed his titanium dental implants may be responsible.[62]

On August 19, 2013, it was reported that the 87-year-old Van Dyke was rescued from his Jaguar by a passerby after the car had caught fire on the US 101 freeway in Calabasas, Los Angeles County. He was not injured in the fire, although the car burned down to its frame.[63]

Van Dyke endorsed Bernie Sanders in the 2016 Democratic Party presidential primaries. In July 2016, while campaigning for Sanders, Van Dyke said of Donald Trump, "He has been a magnet to all the racists and xenophobes in the country. I haven't been this scared since the Cuban Missile Crisis. I think the human race is hanging in a delicate balance right now, and I'm just so afraid he will put us in a war. He scares me."[64]

Van Dyke again endorsed and campaigned for Bernie Sanders in the 2020 Democratic Party presidential primaries.[65]

Works

Books

- Van Dyke, Dick (1967). Altar Egos. F. H. Revell Co. LCCN 67028866.

- Van Dyke, Dick (1970). Ray Parker (ed.). Faith, hope and hilarity. Phil Interlandi (drawings). Garden City, New York: Doubleday. LCCN 70126387.

- Van Dyke, Dick (1975). Those Funny Kids!. Warner Books.

- Van Dyke, Dick (2011). My Lucky Life In and Out of Show Business. Crown Archetype. ISBN 978-0-307-59223-1. LCCN 2010043698. (Van Dyke's memoir)

- Van Dyke, Dick (2015). Keep Moving: And Other Tips and Truths About Aging. Weinstein Books.

Awards and nominations

References

- "Dick Van Dyke to receive SAG career award". BBC. August 21, 2012. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- "Dick Van Dyke to Get SAG Life Achievement Award". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- "Hollywood Walk of Fame". Archived from the original on June 7, 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- "Van Dyke, Dick: U.S. Actor". Museum of Broadcast Communications. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- "The Van Dyke – Smith Research – Person Page". Vandyke-smith-family.com. Archived from the original on February 10, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- "The Family Forest Descendants of Lady Joan Beaufort". Books.google.com. p. 4519. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- "Van Dyke recalls learning shocking secret". Today.com. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Dick Van Dyke plays Not My Job". NPR (Wait Wait ... Don't Tell Me!). October 23, 2010. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- "Mayflower group not easy to get into". The Post and Courier. March 23, 2012. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- Van Dyke, Dick. My Lucky Life In and Out of Show Business. New York: Crown Archetype.

- Adir, Karin (1988). The Great Clowns of American Television. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 219. ISBN 0-89950-300-4.

- McGee, Noelle (May 3, 2004). "Van Dyke Gets New Generation of Fans". The News-Gazette. Danville, IL. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- "Phil Erickson". October 21, 2000. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- "Van Dyke, Dick – The Museum of Broadcast Communications". Museum.tv. October 21, 1992. Archived from the original on November 8, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 13, 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Masterworks Broadway/Dick Van Dyke". Sony Music Entertainment. 2011. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- Goodyear, Dana (December 13, 1910). "SUPERCALIFRAGILISTIC". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- New Orleans TV: The Golden Age Archived May 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, documentary produced by WYES-TV New Orleans Channel 12, broadcast July 18, 2009; published at WYES.

- WDSU Serves New Orleans Since 1948, archived from the original on September 27, 2011

- Walker, Dave, That old-time TV: New book celebrates 60 years of local stars, Arcadia, archived from the original on September 18, 2010, retrieved September 17, 2009

- King, Susan (December 6, 2010). "A Step In Time With Dick Van Dyke". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- "The Museum of Broadcast Communications – Encyclopedia of Television". Museum.tv. Archived from the original on November 8, 2011. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- Brooks, Tim; Earl Marsh (2003). The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-45542-8.

- "Dick Van Dyke's prescription for success". CNN. 2008. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- de Bertodano, Helena (January 7, 2013). "Dick Van Dyke: 'I'd Go to Work with Terrible Hangovers. Which If you're Dancing Is Hard' Archived May 10, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- "Dick Van Dyke's forgotten variety show found the perfect way to introduce general audiences to Andy Kaufman". Me-TV Network. August 19, 2019. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- Zmuda, Bob (2000). Andy Kaufman Revealed!: Best Friend Tells All. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-446-93049-9.

- "Van Dyke and Company". Television Academy. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- "Retired Site – PBS Programs – PBS". Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- "Diagnosis Murder S8 | Universal Channel UK". Universalchannel.co.uk. December 13, 1925. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- "The Dick Van Dyke Show Revisited". Television Academy. Archived from the original on July 30, 2019. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- https://m.imdb.com/title/tt0409892/awards Archived January 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine?

- Sharf, Zack. "'WandaVision' Consulted Dick Van Dyke, Filmed in Front of Live Audience to Capture Sitcom Feel". IndieWire. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Van Dyke was unhappy because it became a vehicle for Ann-Margret, see "Dick Van Dyke Dances Through Life", Bill Keveney, USA Today, April 28, 2011.

- Staff writers (June 30, 2003). "Connery 'has worst film accent'". BBC News. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- "How not to do an American accent" Archived September 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. July 21, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- "Countdown: The five worst attempts at a British accent in film". The Oxford Student. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- "Dick van Dyke Plays Not My Job". Wait Wait ... Don't Tell Me!. October 23, 2010. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- King, Susan (December 6, 2010). "A Step In Time With Dick Van Dyke". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

Somebody sent me a British magazine listing the 20 worst dialects ever done in movies. I was No. 2, with the worst Cockney accent ever done. No. 1 was Sean Connery, because he uses his Scottish brogue no matter what he's playing.

- "The Comic". Turner Classic Movies. January 8, 1998. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- "Night At The Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009)". Baseline. 2011. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- "Retire? F- That". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 1, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- "Past Winners Search". The Recording Academy. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- Amazon page for Faith, Hope and Hilarity. ISBN 0385000510.

- "Ownership changes", Broadcasting. August 23, 1965. p. 84. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- "Changing Hands", Broadcasting. July 5, 1982. p. 69. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 2, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hafner, Katie (June 22, 2000). "The Return of a Desktop Cult Classic (No, Not the Mac)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- Hill, Jim (August 11, 2004). "Do you think that TV legends can't master computer animation? Well then ... You clearly don't know Dick". Jim Hill Media. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved November 3, 2007.

- CGI animation of Dick van Dyke dancing to Michael Jackson's Billy Jean, created by himself Archived October 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "Chad Smith Gets Dick Van Dyke Rapping on Kids Album - Spinner - AOL Music". Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- Keveney, Bill (April 27, 2011). "Dick Van Dyke dances through life". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 1, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- O'Connor, Anahad (October 30, 2009). "Michelle Triola Marvin, of Landmark Palimony Suit, Dies at 76". The New York Times.

- "Palimony figure Michelle Triola Marvin Dies". The Globe and Mail. November 26, 2009. Archived from the original (Fee) on November 6, 2009. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- "Dick Van Dyke Opens Up About the Affair That Ended His Marriage". Country Living. August 1, 2016.

- "Pressure of job turns Van Dyke's hair gray". Altus Times. April 21, 1982. Retrieved August 3, 2011. Chris Van Dyke prosecuted the so-called I-5 Killer, Randall Woodfield.

- "Dick Van Dyke's Charity Work, Events and Causes". Looktothestars.org. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- "Dick Van Dyke, 86, Marries 40-Year-Old Makeup Artist". Article and video interview with Van Dyke and Silver, RumorFix.com. March 9, 2012. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- Helena de Bertodano. "Dick Van Dyke: "I'd go to work with terrible hangovers. Which if you're dancing is hard"". Telegraph. Archived from the original on September 25, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- Staff (April 19, 2013). "Dick Van Dyke Cancels New York Appearance over Illness" Archived January 3, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- Rasheed, Sarah (April 18, 2013). "Dick Van Dyke Brain Disorder Forces Actor on Bed Rest" Archived May 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. American Live Wire. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- Staff (May 31, 2013). "Dick Van Dyke Mystery Illness Solved? Actor Blames Dental Implants" Archived June 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The Huffington Post. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- (August 20, 2013). "Dick Van Dyke Helped from Burning Car" Archived August 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. CNN. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- "CNN Newsroom Transcript". cnn.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- Amatulli, Jenna (March 2, 2020). "Dick Van Dyke Hams It Up At Bernie Sanders Rally, Crowd Chants 'We Love Dick'". HuffPost. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- "1961 Tony Award Winners". www.broadwayworld.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- "Dick Van Dyke | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- 2017 Britannias Britannia Award for Excellence in Television, archived from the original on September 20, 2018, retrieved September 19, 2018

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dick Van Dyke. |

- Dick Van Dyke at the Internet Broadway Database

- Dick Van Dyke at IMDb

- Dick Van Dyke at the TCM Movie Database

- "Dick Van Dyke in Danville, Ill and Crawfordsville, Ind" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 17, 2006. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- Dick Van Dyke – Disney Legends profile (requires Flash)

- Dick Van Dyke talks about his career for the Archive of American Television Arts and Sciences (requires Flash)

- Empire – The Worst British Accents Ever – Number 11 – Dick Van Dyke singing in Mary Poppins (1964) (requires Flash)