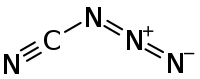

Cyanogen azide

Cyanogen azide, N3CN or CN4, is an azide compound of carbon and nitrogen which is an oily, colourless liquid at room temperature.[1] It is a highly explosive chemical that is soluble in most organic solvents, and normally handled in dilute solution in this form.[1][2][3] It was first synthesised by F. D. Marsh at DuPont in the early 1960s.[1][4]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Carbononitridic azide | |

| Other names

Cyano azide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

PubChem CID |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| CN4 | |

| Molar mass | 68.039 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Cyanogen azide is a primary explosive, although it is far too unstable for practical use as an explosive and is extremely dangerous outside dilute solution.[5][6] Its use in chemistry has been as a reagent prepared in situ for use in the synthesis of chemicals such as diaminotetrazoles, either in dilute solution or as a gas at reduced pressure.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13] It can be synthesised at below room temperature from the reaction of sodium azide with either cyanogen chloride[1] or cyanogen bromide,[4] dissolved in a solvent such as acetonitrile; this reaction must be done with care due to the production from trace moisture of shock-sensitive byproducts.[4][11]

References

- Marsh, F. D.; Hermes, M. E. (October 1964). "Cyanogen Azide". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 86 (20): 4506–4507. doi:10.1021/ja01074a071.

- Goldsmith, Derek (2001). Cyanogen azide. E-EROS Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rc268. ISBN 978-0471936237.

- Houben-Weyl Methods of Organic Chemistry Vol. E 21e, 4th Edition Supplement: Stereoselective Synthesis: Bond Formation, C-N, C-O, C-P, C-S, C-Se, C-Si, C-Sn, C-Te. Thieme. 14 May 2014. p. 5414. ISBN 978-3-13-182284-0.

- Marsh, F. D. (September 1972). "Cyanogen azide". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 37 (19): 2966–2969. doi:10.1021/jo00984a012.

- Robert Matyáš; Jiří Pachman (12 March 2013). Primary Explosives. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 111. ISBN 978-3-642-28436-6.

- Michael L. Madigan (13 September 2017). First Responders Handbook: An Introduction, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-351-61207-4.

- Gordon W. Gribble; J. Joule (3 September 2009). Progress in Heterocyclic Chemistry. Elsevier. pp. 250–1. ISBN 978-0-08-096516-1.

- Science of Synthesis: Houben-Weyl Methods of Molecular Transformations Vol. 17: Six-Membered Hetarenes with Two Unlike or More than Two Heteroatoms and Fully Unsaturated Larger-Ring Heterocycles. Thieme. 14 May 2014. p. 2082. ISBN 978-3-13-178081-2.

- Barry M. Trost (1991). Oxidation. Elsevier. p. 479. ISBN 978-0-08-040598-8.

- Lowe, Derek. "Things I Won't Work With: Cyanogen Azide". Science Translational Medicine. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- Joo, Young-Hyuk; Twamley, Brendan; Garg, Sonali; Shreeve, Jean'ne M. (4 August 2008). "Energetic Nitrogen-Rich Derivatives of 1,5-Diaminotetrazole". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 47 (33): 6236–6239. doi:10.1002/anie.200801886. PMID 18615414.

- Audran, Gérard; Adiche, Chiaa; Brémond, Paul; El Abed, Douniazad; Hamadouche, Mohammed; Siri, Didier; Santelli, Maurice (March 2017). "Cycloaddition of sulfonyl azides and cyanogen azide to enamines. Quantum-chemical calculations concerning the spontaneous rearrangement of the adduct into ring-contracted amidines". Tetrahedron Letters. 58 (10): 945–948. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.01.081.

- Energetic Materials, Volume 1. Plenum Press. pp. 68–9. ISBN 9780306370762.