Cyclopamine

Cyclopamine (11-deoxojervine) is a naturally occurring chemical that belongs in the family of steroidal alkaloids. It is a teratogen isolated from the corn lily (Veratrum californicum) that causes fatal birth defects. It prevents the embryonic brain from separating into two lobes (an extreme form of holoprosencephaly), which in turn causes the development of a single eye (cyclopia). The chemical was named after this effect, as it was originally noted by Idaho lamb farmers who contacted the US Department of Agriculture after their herds gave birth to cycloptic lambs in 1957. It then took more than a decade to identify the corn lily as the culprit.[1] Later work suggested that different rain patterns caused the sheep to graze differently, impacting the amount of corn lily ingested by pregnant sheep.[2] The poison interrupts the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway during development, thus causing birth defects.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(2′R,3S,3′R,3′aS,6′S,6aS,6bS,7′aR,11aS,11bR)-1,2,3,3′a,4,4′,5′,6,6′,6a,6b,7,7′,7'a,8,11,11a,11b-octadecahydro-3′,6′,10,11b-tetramethyl-spiro[9H-benzo[a]fluorene-9,2′(3′H)-furo[3,2-b]pyridin]-3-ol | |

| Other names

• 11-Deoxojervine • (3β,23R)-17,23-Epoxyveratraman-3-ol | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.156.363 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C27H41NO2 | |

| Molar mass | 411.630 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Discovery and naming

In 1957 Idaho sheep ranchers contacted the US Department of Agriculture when their sheep gave birth to lambs with a fatal singular eye deformity. After collecting local flora and feeding it to mice, they struggled to recreate the cyclopia. After a decade of trial and error, they came across wild corn lilies and advised the ranchers to avoid the corn lilies. Cyclopamine was one of three steroidal alkaloids isolated from corn lily, but the only unknown at the time, and it was named after its effects on sheep embryos. Four decades later a team lead by Professor Phillip Beachy related the sonic hedgehog gene to cyclopamine. Upon experimentation, they recreated cyclopia by silencing the sonic hedgehog gene. Professor Beachy then connected their cycloptic results to the cycloptic sheep noted four decades earlier.[1]

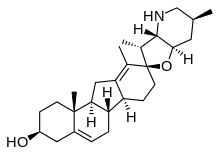

Source and structure

The biosynthesis of cyclopamine begins with cholesterol. A steroid skeleton has a classic 6-member ring, adjacent to another 6, 6, then a five or “6-6-6-5”. Veratrum was determined to contain five types of alkaloids, each of which had a common cholesterol precursor: (1) solanidine alkaloids, (2) verazine alkaloids, (3) vertramine alkaloids, (4) jervine alkaloids, and (5) the cevanine alkaloids. In biosynthesis, Cyclopamine has a solanide (1) precursor, which itself is made from cholesterol. This was determined by initial studies which isolated alkaloids from corn lily (Veratrum californium), and introduced these to embryonic sheep. At the time, jervine was an already known alkaloid which was isolated from corn lily alongside two other alkaloids: the unknown cyclopamine and veratramine; each with different toxicities. Later studies then demonstrated that jervine degraded to cyclopamine upon a Wolff-Kishner reduction, which helped identify the unknown compound.[3]

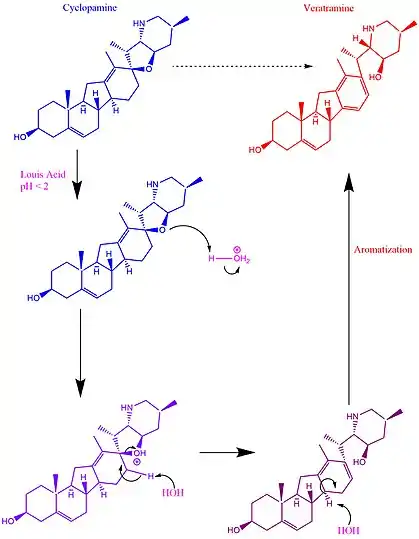

It was also demonstrated that treatment of cyclopamine with a Lewis acid (pH < 2) leads to the production of veratramine. The stomach provides these conditions, and thus only a small amount of cyclopamine passes through the stomach after ingestion. And even though only a small amount of ingested cyclopamine passes the stomach, it remains unaffected afterwards.

Veratramine is highly toxic, even if it does not impact development, as it excites the central nervous system and can cause seizures – similarly to serotonin.[3] The mechanism for the production of veratramine focuses on the cleavage of a carbon-oxygen bond, which leads to the formation of a new double bond. From there, this ring is almost aromatic. The driving force to become aromatic then pushes an elimination reaction, creating a third double bond and producing aromaticity, as depicted in the figure below.

Mechanism

Cyclopamine impacts embryonic development by hindering the sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway.

In healthy development, the Shh gene codes for Shh proteins. These proteins have a high affinity for a surface membrane protein called “Patched”. Upon binding, Shh proteins inhibit Patched. With Patch inhibited, another surface membrane protein called “Smoothened” may signal further cascades which impact development.

Cyclopamine has a high affinity for Smoothened – and upon binding, inhibits the signal. Even though Shh may inhibit Patched, Smoothened cannot signal in the presence of Cyclopamine and thus the pathway is interrupted.[1]

Embryological

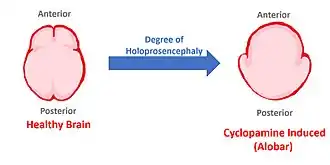

Cyclopamine causes the most advanced form of holoprosencephaly. Because it blocks Shh signaling, the embryonic brain no longer divides into lobes (becomes alobar). Thus, only one optical track develops, hence the cycloptic (singular) eye. Furthermore, this disease is fatal and presently has no cure.[4]

One can imagine one half of the healthy brain not dividing, but instead growing out and resembling the alobar brain. This occurs in cases of cyclopamine poisoning. This malformation is always fatal, and it is worth noting that there are lesser cases of holoprosencephaly that aren't always fatal. However, embryonic cyclopamine poisoning causes the most extreme and therefore fatal cases.[2]

Medical potential

Cyclopamine is currently being investigated as a treatment agent in basal cell carcinoma, medulloblastoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma, tumors that commonly result from excessive SHh activity,[5] glioblastoma, and as a treatment agent for multiple myeloma. For example, studies of epithelial cancers have demonstrated that tumor cells secrete Shh ligand to signal adjacent growth factors production by stromal cells which leads to angiogenesis, tumor cell proliferation, and tumor cell survival.[2][3]

With this in mind, one can imagine cyclopamine as a way of attenuating cancer’s mechanism. However, while cyclopamine has been demonstrated to inhibit tumor growth in mouse xenograft models, it never reached therapeutic potential as it caused many side effects including weight loss, dehydration, and death in mouse models.[3][2]

Having said that, two functional analogs of cyclopamine have been approved by the FDA; vismodegib in 2012, and sonidegib in 2015. Furthermore, vismodegib was the first Shh pathway drug approved for treating cancer.[6]

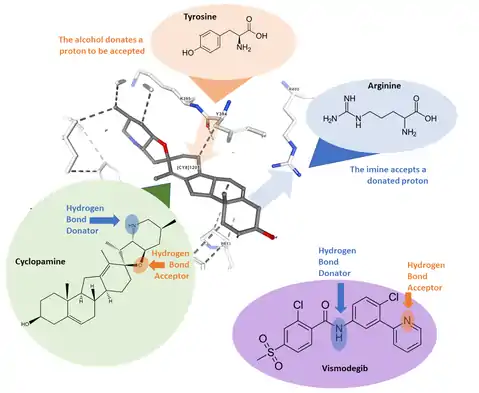

While cyclopamine and vismodegib do not appear very similar, the development of vismodegib revealed which aspects of cyclopamine give it functionality and used those results to make vismodegib. For example, the added chlorine group in Vismodegib gives the drug a much higher solubility than cyclopamine – low solubility is a hindrance towards making cyclopamine a practical drug. The development of vismodegib revealed structure activity relationships (SAR), and determined that hydrogen bonding in two sites, as well as solubility, impact the effectiveness of the drug. Specifically speaking, the two hydrogen bonds work in opposite ways; at one site a tyrosine residue on the Smoothened receptor offers a proton to be accepted whereas a separate arginine residue works as a hydrogen bond acceptor. While the accepting group is more impactful, having both makes for stronger binding.[6]

See also

- Saridegib (also known as IPI-926), a semisynthetic analog of cyclopamine

- Vismodegib, an artificial Hh signaling inhibitor

- Sonidegib, an artificial Hh signaling inhibitor

- Steroidal alkaloid, the family of molecules cyclopamine falls in

References

- "The strange case of the cyclops sheep - Tien Nguyen". TED-Ed. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- Heretsch P, Tzagkaroulaki L, Giannis A (May 2010). "Cyclopamine and hedgehog signaling: chemistry, biology, medical perspectives". Angewandte Chemie. 49 (20): 3418–27. doi:10.1002/anie.200906967. PMID 20429080.

- Rimkus TK, Carpenter RL, Qasem S, Chan M, Lo HW (February 2016). "Targeting the Sonic Hedgehog Signaling Pathway: Review of Smoothened and GLI Inhibitors". Cancers. 8 (2): 22. doi:10.3390/cancers8020022. PMC 4773745. PMID 26891329.

- Hytham Nafady (2015-09-13). "Congenital brain malformations". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Taipale J, Chen JK, Cooper MK, Wang B, Mann RK, Milenkovic L, Scott MP, Beachy PA (August 2000). "Effects of oncogenic mutations in Smoothened and Patched can be reversed by cyclopamine". Nature. 406 (6799): 1005–9. doi:10.1038/35023008. PMID 10984056.

- Dr. Sutherlin, Dan (2017). "Discovering Vismodegib in the Fight Against Skin Cancer: The First Approved Inhibitor of the Hedgehog Pathway" (PDF). American Chemical Society.

Further reading

- Alam MM, Sohoni S, Kalainayakan SP, Garrossian M, Zhang L (February 2016). "Cyclopamine tartrate, an inhibitor of Hedgehog signaling, strongly interferes with mitochondrial function and suppresses aerobic respiration in lung cancer cells". BMC Cancer. 16 (1): 150. doi:10.1186/s12885-016-2200-x. PMC 4766751. PMID 26911235.

- Cancer Drug Behind Cyclops Birth?, Wired News

- Bar EE, Chaudhry A, Lin A, Fan X, Schreck K, Matsui W, Piccirillo S, Vescovi AL, DiMeco F, Olivi A, Eberhart CG (October 2007). "Cyclopamine-mediated hedgehog pathway inhibition depletes stem-like cancer cells in glioblastoma". Stem Cells. 25 (10): 2524–33. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0166. PMC 2610257. PMID 17628016. Lay summary – ScienceDaily (August 31, 2007).

- Tabs S, Avci O (2004). "Induction of the differentiation and apoptosis of tumor cells in vivo with efficiency and selectivity". European Journal of Dermatology. 14 (2): 96–102. PMID 15196999.

- Taş S, Avci O (2004). "Rapid clearance of psoriatic skin lesions induced by topical cyclopamine. A preliminary proof of concept study". Dermatology. 209 (2): 126–31. doi:10.1159/000079596. PMID 15316166.

- Zhang J, Garrossian M, Gardner D, Garrossian A, Chang YT, Kim YK, Chang CW (February 2008). "Synthesis and anticancer activity studies of cyclopamine derivatives". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 18 (4): 1359–63. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.017. PMID 18221872.

- Fan Q, Gu D, He M, Liu H, Sheng T, Xie G, Li CX, Zhang X, Wainwright B, Garrossian A, Garrossian M, Gardner D, Xie J (July 2011). "Tumor shrinkage by cyclopamine tartrate through inhibiting hedgehog signaling". Chinese Journal of Cancer. 30 (7): 472–81. doi:10.5732/cjc.011.10157. PMC 4013422. PMID 21718593.