Cysteamine

Cysteamine is a chemical compound that can be biosynthesized in mammals, including humans, by the degradation of coenzyme A. The intermediate pantetheine is broken down into cysteamine and pantothenic acid.[10] It is the biosynthetic precursor to the neurotransmitter hypotaurine.[11][10]

| |

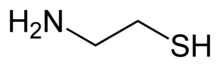

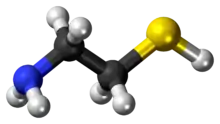

Skeletal formula (top) Ball-and-stick model of the cysteamine | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Cystagon, Procysbi, Cystaran, others |

| Other names | 2-Aminoethanethiol, β-Mercaptoethylamine, 2-Mercaptoethylamine, decarboxycysteine, thioethanolamine, mercaptamine bitartrate, cysteamine (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, eye drops |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.421 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C2H7NS |

| Molar mass | 77.15 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 95 to 97 °C (203 to 207 °F) |

| |

| |

It is a stable aminothiol, i.e., an organic compound containing both an amine and a thiol functional groups. Cysteamine is a white, water-soluble solid. It is often used as salts of the ammonium derivative [HSCH2CH2NH3]+[12] including the hydrochloride, phosphocysteamine, and bitartrate.[10]

As a medication, cysteamine, sold under the brand name Cystagon among others, is indicated to treat cystinosis.[4][5][6]

Medical uses

Cysteamine is used to treat cystinosis. It is available by mouth (capsule and extended release capsule) and in eye drops.[13][6][7][4][8][5][9][14]

Adverse effects

Topical use

The most important adverse effect related to topical use might be skin irritation.

Oral use

The label for oral formulations of cysteamine carry warnings about symptoms similar to Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, severe skin rashes, ulcers or bleeding in the stomach and intestines, central nervous symptoms including seizures, lethargy, somnolence, depression, and encephalopathy, low white blood cell levels, elevated alkaline phosphatase, and idiopathic intracranial hypertension that can cause headache, tinnitus, dizziness, nausea, double or blurry vision, loss of vision, and pain behind the eye or pain with eye movement.[6]

The main side effects are Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, severe skin rashes, ulcers or bleeding in the stomach and intestines, central nervous symptoms, low white blood cell levels, elevated alkaline phosphatase, and idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). IIH can cause headache, ringing in the ears, dizziness, nausea, blurry vision, loss of vision, and pain behind the eye or with eye movement.

Additional adverse effects of oral cysteamine include bad breath, skin odor, vomiting, nausea, stomach pain, diarrhea, and loss of appetite.[6]

The drug is in pregnancy category C; the risks of cysteamine to a fetus are not known but it harms babies in animal models at doses less than those given to people.[4][5]

For eye drops, the most common adverse effects are sensitivity to light, redness, and eye pain, headache, and visual field defects.[5]

Interactions

There are no drug interactions for normal capsules or eye drops,[4][5] but the extended release capsules should not be taken with drugs that affect stomach acid like proton pump inhibitors or with alcohol, as they can cause the drug to be released too quickly.[6] It doesn't inhibit any cytochrome P450 enzymes.[6]

Pharmacology

People with cystinosis lack a functioning transporter (cystinosin) which transports cystine from the lysosome to the cytosol. This ultimately leads to buildup of cystine in lysosomes, where it crystallizes and damages cells.[13] Cysteamine enters lysosomes and converts cystine into cysteine and cysteine-cysteamine mixed disulfide, both of which can exit the lysosome.[6]

Biological function

Cysteamine also promotes the transport of L-cysteine into cells, that can be further used to synthesize glutathione, which is one of the most potent intracellular antioxidants.[10]

Cysteamine is used as a drug for the treatment of cystinosis; it removes cystine that builds up in cells of people with the disease.[15]

History

First evidence regarding the therapeutic effect of cysteamine on cystinosis dates back to 1950s. Cysteamine was first approved as a drug for cystinosis in the US in 1994.[6] An extended release form was approved in 2013.[16]

Society and culture

It is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA).[13][6][7][8][9][17][18]

In 2013, the regular capsule of cysteamine cost about $8,000 per year; the extended release form that was introduced that year was priced at $250,000 per year.[16]

Research

It was studied in in vitro and animal models for radiation protection in the 1950s, and in similar models from the 1970s onwards for sickle cell anemia, effects on growth, its ability to modulate the immune system, and as a possible inhibitor of HIV.[10]

In the 1970s it was tested in clinical trials for Paracetamol toxicity which it failed, and in clinical trials for systemic lupus erythematosus in the 1990s and early 2000s, which it also failed.[10]

Clinical trials in Huntington's disease were begun in the 1990s and were ongoing as of 2015.[10][19]

As of 2013, it was in clinical trials for Parkinson's disease, malaria, radiation sickness, neurodegenerative disorders, neuropsychiatric disorders, and cancer treatment.[15][10]

It has been studied in clinical trials for pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[20]

References

- "Cystagon 150 mg hard capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 19 June 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Cystadrops 3.8 mg/mL eye drops solution - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 19 June 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "Procysbi 25 mg gastro-resistant hard capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 17 September 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "Cystagon- cysteamine bitartrate capsule". DailyMed. 29 January 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Cystaran- cysteamine hydrochloride solution". DailyMed. 22 November 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Procysbi- cysteamine bitartrate capsule, delayed release pellets Procysbi- cysteamine bitartrate granule, delayed release". DailyMed. 23 March 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Procysbi EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Cystagon EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Cystadrops EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Besouw M, Masereeuw R, van den Heuvel L, Levtchenko E (August 2013). "Cysteamine: an old drug with new potential". Drug Discovery Today. 18 (15–16): 785–92. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2013.02.003. PMID 23416144.

- Singer TP (1975). "Oxidative Metabolism of Cysteine and Cystine". In Greenberg DM (ed.). Metabolic pathways. 7. Metabolism of sulfur compounds (3rd ed.). New York: Academic Press. p. 545. ISBN 9780323162081.

- Reid EE (1958). Organic Chemistry of Bivalent Sulfur. 1. New York: Chemical Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 398–399.

- Nesterova G, Gahl WA (6 October 2016). "Cystinosis". In Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJ, Stephens K, Amemiya A (eds.). GeneReviews. Seattle WA: University of Washington. PMID 20301574.

- Shams F, Livingstone I, Oladiwura D, Ramaesh K (10 October 2014). "Treatment of corneal cystine crystal accumulation in patients with cystinosis". Clinical Ophthalmology. 8: 2077–84. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S36626. PMC 4199850. PMID 25336909.

- Besouw M, Masereeuw R, van den Heuvel L, Levtchenko E (August 2013). "Cysteamine: an old drug with new potential". Drug Discovery Today. 18 (15–16): 785–92. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2013.02.003. PMID 23416144.

- Pollack A (30 April 2013). "F.D.A. Approves Raptor Drug for Form of Cystinosis". The New York Times.

- "Drug Approval Package: Cystaran (cysteamine) NDA #200740". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 26 August 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "Drug Approval Package: PROCYSBI (cysteamine bitartrate) Delayed-Release Capsules NDA #203389". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 December 1999. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Shannon KM, Fraint A (September 2015). "Therapeutic advances in Huntington's Disease". Movement Disorders. 30 (11): 1539–46. doi:10.1002/mds.26331. PMID 26226924. S2CID 31037666.

- Mitchel EB, Lavine JE (November 2014). "Review article: the management of paediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 40 (10): 1155–70. doi:10.1111/apt.12972. PMID 25267322. S2CID 21263419.

External links

- "Cysteamine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Cysteamine hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.