Dano-Swedish War of 1808–09

The Dano-Swedish War of 1808–1809 was a war between Denmark–Norway and Sweden due to Denmark–Norway's alliance with France and Sweden's alliance with the United Kingdom during the Napoleonic Wars. Neither Sweden nor Denmark-Norway had wanted war to begin with but once pushed into it through their respective alliances, Sweden made a bid to acquire Norway by way of invasion while Denmark-Norway made ill-fated attempts to reconquer territories lost to Sweden in the 17th century. Peace was concluded on grounds of status quo ante bellum on 10 December 1809.

| The Dano-Swedish War of 1808–1809 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars and the English Wars | |||||||

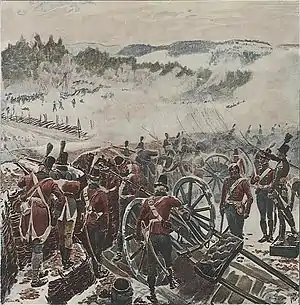

Norwegian soldiers on the march towards the Swedish-Norwegian border during the initial phase of the war | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Co-belligerent: Supported by: |

Co-belligerent: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Denmark–Norway: 36,000 French Empire: 45,000 Total: 81,000 | 23,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

210–400 killed or wounded 152 captured |

200 killed or wounded 900–1,200 captured | ||||||

Background

During the War of the First Coalition Denmark-Norway and Sweden had remained neutral. The two Nordic countries also intended to follow this policy during the War of the Second Coalition and had in 1800, together with Prussia and Russia, formed the Second League of Armed Neutrality in order to protect their neutral shipping against the British policy of unlimited search of neutral shipping for French contraband. The League would however, be dissolved following the British naval attack against Copenhagen and the death of Tsar Paul I of Russia in 1801. After the collapse of the alliance, and Denmark-Norway's brief war against the United Kingdom, Sweden and Denmark still continued their neutrality policy.

In 1805 Sweden joined the war against France, but following the rapid French advance through northwest Germany and the defeat at Lübeck, Swedish forces had to withdraw to Swedish Pomerania. Attempts at peace negotiations between France and Sweden was initiated, and Emperor Napoleon I of France offered Sweden in the autumn of 1806, Norway in exchange for Swedish Pomerania.[1] But the negotiations failed, and in early 1807 French forces invaded and eventually occupied Swedish Pomerania.

Following the Treaties of Tilsit in 1807 the main focus of France and Britain was directed towards Denmark. Napoleon wanted to include the neutral Denmark-Norway in the Continental System while the United Kingdom feared that the Danish fleet should fall into the hands of the French. Britain's attack and subsequent bombardment of Copenhagen led to the seizure and destruction of large parts of the Danish fleet and the Danish choice to conclude an alliance with Napoleon.[1] The alliance between Denmark-Norway and France was signed at Fontainebleau on 31 October 1807. The agreement indicated vague promises from the French that they would help Denmark-Norway regaining its fleet, while Denmark had to commit themselves to participate in an eventual war against Sweden together with France and Russia. Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark-Norway was reluctant to participate in war against Sweden, but he decided to declare war against Sweden with the aim of conquering the territory which Denmark-Norway had lost after the Treaty of Brömsebro and Treaty of Roskilde.[1] And since Sweden's attention was on Finland following the Russian invasion in February 1808,[2] he saw it as easier to take back the territories. On 14 March 1808 the Danish Minister in Stockholm presented the declaration of war to the Swedish government,[3] and the Swedish king, Gustav IV Adolf replied with planning an invasion of Själland, in order to force Denmark to conclude separate peace. This plan was however, temporarily sidelined and the Swedish troops in Götaland were instead placed in a defensive position, following rumors that Napoleon had sent reinforcements to Denmark. King Gustav IV instead approved the plan drawn up by Gustaf Mauritz Armfelt, on an invasion of Norway to compensate for a possible loss of Finland.

Armies

The Swedish army

The Swedish army stationed in Sweden counted a total of 23,000 men, 7,000 in southern Sweden under the command of Count Johan Christopher Toll,[4] 14,000 towards the Norwegian border under the leadership of Gustaf Mauritz Armfelt,[2] and 2,000 in Norrland under Johan Bergenstråhle.

The Swedish army was fairly well equipped and the soldiers were well trained, but under the pressure from two fronts the Swedes had been forced to retain the ability to send troops wherever they were needed the most. The main theater of war was in the east, where the Russian invasion threatened the Swedish rule in Finland,[5] but the threat from Denmark–Norway and France was taken seriously. The Swedish western army was divided into two wings, the right wing was led by Armfeldt himself,[3] and the left wing was led by Major General Vegesack.[6]

The army's right wing furthermore consisted of Colonel Carl Pontus Gahn's "Flying Corps" of approximately 650 men in Dalby, Colonel Leyonstedt's 1st Brigade of approximately 1,600 men in Eda, Colonel Schwerig's 2nd Brigade of about 2,500 men in Töcksmark, Colonel Bror Cederström's 3rd Brigade of approximately 1,750 men in Holmedal, and Colonel Johan Adam Cronstedt's 4th Brigade of approximately 1,700 men in the area east of the Marker. The army's left wing consisted mainly of one brigade at Strömstad, one at Töftedal and one in the area between Gothenburg and Uddevalla.[6]

Swedish regiments

The Danish-Norwegian army

The Danish-Norwegian army combined consisted of 36,000 men.[8] The Danish army could muster 14,650 men, but only 5,000 of them could be used for attacks against the Swedish. The Norwegian army had been prepared for a future war with Sweden since the fall of 1807, but since they were forced to organize coastal protection along the long Norwegian coast against attacks from the British warships who tried to close the connecting lines between Norway and Denmark, the army was in a poor state in late February 1808. The army ended up with a lack of weapons, ammunition, clothes, food and many soldiers had equipment that was close to 20 years old.

The Norwegian army was under the leadership of Prince Christian August of Augustenburg who at that time was President of the Norwegian Government Commission, which had been established when the British initiated the blockade between Norway and Denmark in 1807. Christian August would later during the war also be appointed Governor-general of Norway.[9]

The Norwegian army

- 24 dragoon companies totalling about 1,800 riders[10]

- 14 musketeer battalions (each with 4 divisions) for a total of about 8,400 men[10]

- 10 sharpshooter companies totaling about 1,200 men[10]

- 10 depot battalions (each with 3-4 divisions) for a total of about 5,000 men[10]

- 8 grenadier battalions (each with 4 divisions) for a total of about 4,800 men[10]

- 6 fortress batteries totaling about 300 men[10]

- 3 Field batteries (1 and 2 mounted marching batteries) totaling approximately 300 men[10]

- 2 ski battalions (each with 3 companies) totaling about 600 men[10]

- 1 jäger battalion (4 companies) of added 600, later 720 men[10]

- A light battalion (6 companies) of about 600 men[10]

- A pioneer company of about 150 men[10]

Stattholder Christian August had only 8,000 men available at the beginning of the war along the border from Svinesund to Trøndelag, and they had to take in many untrained recruits in order to fill up the ranks.[10]

The Norwegian defence

After the stationing of the troops at the border was completed in late March 1808, Christian August divided the southern forces along the border on Østlandet from south to north:

- Colonel Hans Gram Holst's right-wing brigade with approximately 3,400 men in the area from Svinesund to Rødenes[10]

- Colonel Werner de Seues's center brigade with about 1,900 men in the area from Rødenes to Kongsvinger[11]

- Colonel Bernhard Ditlef von Staffeldt's left-wing brigade with roughly 1,300 men in the area from Kongsvinger to Elverum[12]

- Colonel Christopher Frederik Lowzow's 1st reserve brigade with some 1,700 men in the area from Vormsund to Fetsund[13]

- Colonel Johan Andreas Ohme's 2nd reserve brigade with approximately 650 men from Grønsund to Fetsund[14]

The Norwegian troops in the southern defense amounted to about 9,000 men, in addition, there were 3,300 men stationed in Trøndelag for the defense in the north:[13]

- Colonel Carsten Gerhard Bang with a brigade of about 2,100 men in Røros[14]

- Lieutenant General Carl von Schmettow with a brigade of about 1,200 men in Innherred[15]

It was also stationed 2,000 men in Trondheim and Kristiansand, and 6,200 men in Frederiksvern and Bergen[14]

Fortress garrisons

- Fredrikstad: about 2,350 men[14]

- Fredriksten: about 1,250 men[14]

- Kongsvinger Fortress: about 900 men[16][17]

- Akershus Fortress: about 800 men[14]

The French army

At the outbreak of war Napoleon had sent reinforcements to Denmark from France, Spain and the Netherlands under the leadership of Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte (a total of about 45,000 men, 12,500 French, 14,000 Spaniards, 6,000 Dutch and a Danish reserve squad of 12,500 men), which meant that the Danish-French force consisted of approximately 81,000 men. The French made it a condition for their participation in the war against Sweden that the coalition army was to be under French command.

War preparations

On 5 March, several days before the Danish government had decided to declare war on Sweden, Marshal Bernadotte, who at that time was French governor of Hamburg and the other Hanseatic cities, started his march towards Denmark with the coalition army of 32,000 men. But it seems likely that Napoleon at the time was not willing to let their troops go into direct action, because after Bernadotte had camped with large parts of the coalition army on Sjælland he was not ordered to continue his advance against the Danish shipping ports.

The ice also started breaking up in mid-March, and to everyone's surprise, the first British warships started to show up even as ice floes still lay densely packed. Admiral Hyde Parker had wintered in Gothenburg the winter of 1807-08 with his squadron and came down very early in the straits between the Kattegat and Baltic Sea. Bernadotte, who had lost valuable time while lying ice-bound, also lost the ability to secure passage before the arrival of the British warships.

The troops presence in Sjælland, Fyn and Jutland was more a burden than help to the Danish population. Another problem arose after the news that Spain had revolted against Napoleon was known in Denmark, and the Spanish troops had to be disarmed and interned. In mid-April 1808 the Danish-French plan for an invasion of Sweden was called off and attention was directed towards the Swedish-Norwegian border.

The war

Swedish invasion of Norway

In the last days of March, the Norwegian and Swedish outposts along the border had been in contact with each other on several occasions, but the scattered skirmishes had been fruitless. The first major action happened on 1 April 1808, when Johan Bergenstråhle marched with his 2,000 men into Norway from Jämtland,[18] but his army was forced to retreat back to Sundsvall without engaging in battle. But at the same time as Bergenstråhle's retreat two companies of 235 men under Major Gyllenskrepp went across the border from Herjedalen towards Røros and engaged in a minor skirmish with a Norwegian field guard of 40 men from Colonel Bang's brigade in Aursund. After the field guards had withdrawn and the Norwegian outposts of 140 men, of which the field guard was a part of, had retreated to Røros, the Swedes began with unusually extensive looting in the border area, and especially in the town of Brekken. The looting continued until those of Colonel Bang's forces who were closest in the area, a Musketeer battalion of 600 men under Major Sommerschild, counterattacked and forced the Swedes back across the border.

In retaliation for the sacking of Brekken a force of 558 men from Colonel Bangs's Brigade marched across the border to Malmagen and Ljusnedal on 8 April. The royal properties in Funnesdalen were sacked and devastated in the purely predatory expedition, and all the loot that had been taken from Brekken, including 22 guns, was recaptured in Ljusnedal after a brief skirmish with the Swedish defenders.

Since the spring should prove to be quite uneventful in the border area between Trøndelag and Jämtland after the engagements in early April, the Norwegians decided to send several units to the south of Røros, and to the area between Roverud and Kongsvinger.

The Swedish main attack to the south began on the night of 14 April with the advance of the Swedish 2nd brigade in the area of Aurskog-Høland.[19] Christian August, who was on his way to move his headquarters to Rakkestad, was notified of the Swedes' advances and marched a brigade to meet the threat from the east on 17 April.[19] His choice of interior lines of operation proved suitable for a defensive position, so he could concentrate his forces against the front section where they were needed the most. Fighting in Høland and Aurskog ended with a Norwegian victory, and the Swedish commander, Colonel Schwerin felt so threatened by the Norwegian counterattacks that he ordered a retreat after the defeat at Toverud, where the Swedish commander Count Axel Otto Mörner and his troops had been forced to surrender.[20] Schwerin saved himself from a decisive battle against the Norwegian army because Christian August had decided to move his forces back to Kongsvinger to accommodate the Swedish advance in area and from there try to mount a major attack.

Fighting around Kongsvinger

In the border district at Eidskog, Gustaf Mauritz Armfeldt began this advance with about 1,600 men from across the border at Eda towards Kongsvinger on the evening of 15 April.[21] He drove out the weak border guard and continued advancing towards the Lier entrenchment in the course of several days of spread skirmishes. The Norwegian defenders was forced to retreat in order to avoid being outflanked by the Swedes.

On 18 April, a battle took place at Lier, about one mile south of Kongsvinger. In the battle 1,000 Swedish soldiers defeated a Norwegian army consisting of 800-900 men under the command of Major Bernt Peter Kreutz.[22] After this victory the Swedish troops entrenched themselves at Lier and advanced all the way to the river Glomma, but they did not risk an attack on Kongsvinger Fortress,[23] something that put an temporarily end to the offensive.[24]

Christian August reacted severely to the news of the defeat at the Lier and that the Swedish troops had reached the river Glomma. He now had to move the main forces to Blaker to stop a possible attack from the Swedish positions on the south-west side of Kongsvinger in the north or from Høland in the south. But fortunately for the Norwegians the outcome of the battle of Toverud and the engagement at Lund stabilized the situation in the south. Armfeldt therefore wanted to besiege and then attack Kongsvinger and thereby secure the strategically important fortress. Colonel Carl Pontus Gahn with his "Flying Corps" was with this ordered to make his way to Glomma and from there west towards Kongsvinger, Armfeldt would thereby make a pincer movement to besiege the fortress. The order given to Colonel Gahn about such a bold and perilous advance has always been controversial, as superior Norwegian forces of approximately 800 men were stationed by the Flisa river which he had to pass. Gahn marched from the Swedish camp at Midtskogen on the evening of 24 April with about 500 men along the snowy road to Flisa river and along the river down towards Trangen to the southwest of Nyen in Åsnes. From Nyen, major Norwegian forces advanced down to attack the Swedes from the rear, and together with Colonel Staffeldt brigade of about 1,050 men, the approximately 800 Norwegian troops stationed in the area participated in the attack.[23] The battle of Trangen was a serious defeat for the Swedes.[25] The whole corps was annihilated and about 440 men were captured at Trangen,[26] and another 65 on 25 April at Midtskogen. After the battles, Colonel Staffeldt was ordered to move his brigade west to Kongsvinger to reinforce the defense of the fortress.[27] After the regrouping of the defense around Kongsvinger, Christian August traveled south to get the Swedes forestalled by an offensive in the area around Ørje.

When Armfeldt was notified of the defeat in the north, he immediately feared a Norwegian attack on this flank as long as there was ice on Glomma. The Swedish commander had lost his right flank to the north, and strong Norwegian forces had gathered along the Glomma at Kongsvinger and Blaker.[28] Because of this Armfeldt found it necessary to wait for Colonel Vegesack and his forces, who had not yet begun their advance, before he carried out some further operations and thereby chose to go into a defensive position.

Battles in Smaalenene

Prince Christian August had initially planned to attack from Blaker against the Swedish 3rd Brigade at Ørje, but got messages that indicated that a Swedish attack across the border to the south would come in the near future. Because from 2–3 May, about 2,000 Swedish soldiers from two Swedish brigades under Colonel Vegesack advanced forward in three columns between Holmgil and Prestebakke east of Fredrikshald. But the conditions for the Swedish troops were so bad that the advance was stopped at the Norwegian defensive line between Halleröd, Gjeddeludd, Enningdalen and Berby church.

Meanwhile, further north, a Swedish force of about 1,000 men advanced out of Nössemark across the border towards Bjørkebekk and Skotsund in Aremark, but this advance were also stopped. During the month of May the Swedish troops entrenched themselves along a line from the southeast of Kongsvinger, behind Haldenvassdraget from Kroksund and along the new line from Aremark to Iddefjorden.

The Norwegian offensive that had been planned, was abandoned in favor of the realignment of the standing forces, including Colonel Holst's brigade that had been lying northeast of Rødnessjøen and had moved back to Mysen. A limited offensive against the Swedish brigade at Ørje was instead initiated with about 1,000 men who were directed over Mjerma under the command of Major Andreas Samuel Krebs on 4 May. The fighting around Aremark on 5 May was tough, but the Swedish troops eventually fled their positions back to the well-developed positions outside of Ørje, where they managed to hold out. The Norwegians had 10 wounded after the battle, while the Swedes had 10 dead and 16 wounded, and Krebs with his exhausted troops were recalled, while Major Friederich Fischer with his (approximately) 500 men went on from Mysen and came as a surprise to the Swedish field guards at Ysterud and Li, west of Ørje, on 7 May. But despite of the loss of only 9 wounded, Fischer was unable to continue because Ørje bridge was destroyed by the Swedes.[29]

It was also inserted several other local attacks against the Swedish positions, and on the night of 8 May, Major Peter Krefting advanced with three divisions against Skotsberg to break the link between the Swedish forces in Aremark and Ørje. But the Norwegian attack was beaten back under the first action at Skotsberg, where a strait separated the Swedes and Norwegians from each other. Krefting tried again to cross the strait during the second encounter at Skotsberg on 13 May with artillery and four mortars, but was stopped again.

On 9 May Lieutenant Johan Spørck advanced with 120 men from Fredriksten fortress against the Swedish position at Gjeddelund, but were beaten back by a company from Holtet who recaptured the position. After the skirmish at Gjeddelund, Spørck had 1 killed and 6 wounded, while the Swedes had 1 killed, 11 wounded and 2 captured.[30] A new, small offensive further north, took place on 12 May west of Strømsfoss, were, with his modest forces, Captain Hans Harboe Grøn began a series of local attacks against the Swedish field guards. The attacks lasted until 28 May when the Swedes had been reinforced with a battalion.[30]

Swedish withdrawal from Norway

After Colonel Staffeldt had regrouped his forces in Kongsvinger, the front against the fortress was quiet until the beginning of May, apart from some minor skirmishes that was set in to constantly disrupted the Swedes. These minor skirmishes worked to the benefit of the Norwegian troops and on 5 May a Swedish vanguard was wiped out and 10 Swedes were captured. It was much to the chagrin of the Swedish commander that he suffered the loss of patrols and small outposts because of the Norwegian troops' scattered warfare. This led to more concentration of the Swedish troops and the Swedish 2nd Brigade was moved closer to the 1st Brigade in order to prevent the Norwegians from attacking them in small groups. Siege artillery was also transferred to the Kongsvinger front for a new planned attack at Kongsvinger fortress. The Swedes had also initiated the development of new positions at the Lier entrenchment, with evident facing west, and the so-called "Skinnarbøl line" along the river east of Skinnarbøl and Vinger Sea facing north. The Norwegians kept close attention to what was going on at the Swedish positions by continually sending reconnaissance patrols that went out aggressively against the Swedes. Major troop movements were not possible before mid-May because of the huge snowfall that winter, and it was not until 15 May, Staffeldt ordered to make a larger attack on the Swedish right flank. But the conditions were still not good enough, and the roads had only just begun to dry up, so the attack was postponed until 18 May.[31]

Battles at Mobekk and Jerpset

The skirmish at Mobekk did not begin well for the Norwegian soldiers. The Swedes managed to destroy the vital bridge over the river at Overud, and the Norwegian troops were standing on their side against the Swedish defenders who fought doggedly in the barricade.[32] After four hours, the battle of Mobekk came to an end, and the Norwegian troops returned to Kongsvinger.[33]

In order to restore his dignity after the battle of Mobekk, Staffeldt was forced to make a new attack.[34] It had been discovered that a Swedish jäger company had been moved to Jerpset in Vestmarka in order to connect the Swedish 2nd Brigade who was stationed closer to the border. On the 23 May, troops from Captain Wilhelm Jørgensen's light company, along with 65 skiers crossed Glomma approximately 10 km west of Kongsvinger.[34] The Norwegians attacked Jerpset farm in the evening of the 24 May and discovered that the Swedes had sent out several patrols, and that only 29 Swedish soldiers were stationed at the farm. 25 of the 29 Swedish soldiers were taken prisoner.[35] Swedish troops who were quartered at nearby farms were unable to obtain the Norwegians who after the fighting retreated into the woods under cover of darkness.[36] Colonel Staffeldt had planned future attacks, but the events on Jerpset frightened Armfeldt so much that he ordered the withdrawal from the positions closest to Kongsvinger. Besides, he had already on the 19 May received an order from King Gustav IV Adolf of what he believed to be a general retreat.[34]

An English fleet had arrived in Gothenburg with 10,000 men on 18 May 1808, and Gustav IV Adolf now wanted to make a Swedish-English attack against the Danish island Själland, and therefore ordered Armfeldt to «[...]occupy the safest and most favorable defensive position against Norway».[Note 1] King Gustav IV had, however, not intended for Armfeldt to retreat back across the border, but only secure the areas in Norway that he had occupied and wait for the planned invasion of Själland. Armfeldt on the other hand misunderstood the order and abandoned all plans of attack against the Norwegian military and, with the 1st and 2nd Brigade, retreated to secure positions behind the border in order to reorganize the troops and secure border crossings.[37] The Swedish retreat came as a surprise to the Norwegians. Staffeldt advanced on the day after the Swedes' withdrawal all the way to Eidskog with his troops, and on the evening of 31 May his main force arrived at Matrand. Smaller patrols were also sent to Flisa to secure the area. King Gustav IV Adolf's plans for a Swedish-English attack on Själland would, however, be cancelled after the British fleet returned to England on 3 July.

Fighting in Enningdal

The other two Swedish brigades that had been stationed close to Fredrikshald went on 8–9 June back across the border together with the parts of the left wing brigade which had reached Skotfoss. In mid-June there were only two Swedish positions left on Norwegian territory, something that came as a surprise to the Norwegians. Christian August had originally planned a general offensive against the south to Rødenes/Ørjebro and Enningdalen to push the last Swedish troops across the border, but the plan was instead changed into a small offensive. This plan, which had been worked out by the commander on Fredriksten fortress, Lieutenant Colonel Juel, was that one should insert many small attacks against the Swedes to drive them back across the border.[38]

The Swedish troops, under command of Lieutenant Colonel Jacob Lars von Knorring, had stationed themselves at their fortified positions at Prestebakke with strongholds in both the east and west, and with larger forces misplaced by Ende, Berby and Enningdalen. Juel, who was seriously ill, gave the command to Captain Arild Huitfeldt, who began advancing on the evening on 9 June with a force totalling 710 men. The thrust to the south was successful. During the battle of Prestebakke on 10 June, Huitfeldt managed to confuse the Swedish officers with a maneuver that surprised and routed the Swedish forces at Prestebakke.[39] The Swedish casualties totaled 60 dead and severely wounded, and 395 captured (of which 34 were wounded), and two guns.[40] The Swedish force of approximately 420 men were wiped out and a smaller force of about 150 men surrendered at Berby. The Norwegian losses were low with only around 12 casualties. In Sweden, there was a severe reaction to this surprising defeat, and the Swedish commander, Lieutenant Colonel von Knorring, was court-martialed.[41]

After the Swedes had received reinforcements, they counter-attacked against the positions at Prestebakke on 14 June to reconcile their former positions. The main Norwegian force had moved back to Fredriksten fortress with a large number of Swedish prisoners of war, so the outnumbered Norwegian outposts at Prestebakke, Ende and Gjeddelund were driven back after a short battle. But the Swedes left their positions and went back across the border between the 20–24 June, and the Norwegian forces were quick to secure the border areas and to set up border guards. This meant that there were no longer any Swedish troops on Norwegian soil.

Raids and minor campaigns

In the period up to December there were several minor offensives from both the Norwegian and the Swedish side, but these were of little significance to the war. For the Norwegian troops stationed in the north of Kongsvinger and at Matrand there was a prolonged period of constant surveillance, in addition to boredom and poor conditions in the sparsely populated Eidskog with minimal settlement and little food. Many of the soldiers had to live in huts made of pine needles and bark for the rest of the summer and into the autumn. Norwegian raids against civilians on the Swedish side of the border were prohibited. If a Norwegian soldier brought back stolen goods from an attack, they were returned. Officers on both sides were very concerned that their soldiers should behave well towards the civilian population, but the border was sparsely populated and the sparse food supply was quickly used by the military. Poor accommodation, lack of supplies and a scarcity of food began to have a demoralising and debilitating effect on the troops on both sides of the border.

Attack into Eda and Jämtland

Staffeldt, who had been promoted to Major General on 30 June, had kept his troops on the border in Eidskog until early in July, when they were ordered to advance across the border and carry out minor attacks in several places. A column of four companies was sent forward to Morast, another column of two companies to Magnor and a third column of three companies with Major Frederik Wilhelm Stabell to the area south to Vestmarka. Stabell's group continued on from there to Sweden on 18 July, and advanced to the Swedish positions at Adolfsfors. The troops stayed on the Swedish side of the border for two days, before they retreated across the border and back to Matrand.

In August 1808, 644 Norwegian troops from Trøndelag under the commande of Major Coldevin advanced with artillery and mounted dragoons across the border from Verdal and Meråker into Jämtland in the Jämtland Campaign of 1808. Staffeldt also sent troops to Falun in order to support the Norwegian invasion of Jämtland and a force of 200 men advanced to Midtskogen on 10 August. These troops marched from there to Dalby in Sweden, and returned to Baltebøl on 20 August since they could not find any Swedish troops in the area, apart from the border guard at Midtskogen. The main Norwegian offensive into Jemtland was stopped at the entrenchment at Järpen on 15 August and, after two days, Major Coldevin chose to cancel the offensive because the Swedish troops had reinforced the stronghold at Järpen.[42] The campaign ended on 19 August.[43]

Ceasefire

The British blockade of Norway had gradually worsened the situation for the Norwegians, and the few supplies that arrived from Denmark and northern Russia were not enough.[44] Everywhere there were food shortages, and it was impossible to replace the uniforms and other equipment that had been worn out and destroyed after several months in the field. Opportunities to carry out further offensives were also rare, and Christian August therefore decided to keep his troops at the border. Things were not much better for the Swedes in the sparsely populated border regions, since most of the supplies went to the troops fighting against the Russians in Finland. Lieutenant General Bror Cederström had also taken over the command of the border army from Armfeldt, who had left in August as a result of his misunderstanding of the king's orders.

During the autumn it came to negotiations between Christian August and the Swedes, but since it took a while to get contact with King Frederick in Denmark, Christian August had to act largely without the king's approval. He meant that he could not continue hostilities against Sweden because of the distress and lack of supplies among both the population and the soldiers in the country. So in defiance of the king's will he entered into an agreement for the armistice to the southern Norwegian front on 22 November and the Armistice Agreement came into force on 7 December 1808.[45] It could be terminated on 48 hours notice, but was applicable for the rest of the war.

Unfortunately the ceasefire agreement came too late for both the Norwegian and the Swedish army, who were both badly affected by diseases that spread from the east and into the border area, where thousands had lived in appalling conditions for several months. The southern Norwegian army, consisting of around 17,000 men, should during the fall and winter of 1808 experience that half of the soldiers would suffer from disease, and that only between April and September 700 died. In March 1809, approx. 8,700 were admitted to field hospitals, of which 1,200 died. In the Swedish army, the conditions were even worse because diseases such as typhoid and dysentery had spread from the east. The Swedish sources do not have precise information about the total number of sick people, only pieces from the various reports and records of the officers in the army. Morbidity rates had risen from 22% among the troops in September to 25% in November, and 403 Swedish soldiers died that month.

In the winter of 1808-09 no major battles were fought. The Norwegians were lacking supplies and the Swedes were concentrated on the war in the east where the Russians now had managed to occupy the whole of Finland. At the same time dissatisfaction with the absolutist Swedish king had evolved, and there was a desire for a constitution. The Swedish still feared that the Norwegian troops on Østlandet would take advantage of the uprising against the Swedish king, and invade Svealand or Götaland. So the leaders of the revolutionary Swedish forces had to ensure themselves that the Armistice Agreement of 7 December 1808 still was valid. This were ensured through the Kongsvinger Agreement in early March 1809, which was an oral agreement between the Swedish revolutionary forces and Christian August that the Norwegian troops should remain stationary at the border,[46] while the Swedish forces in Värmland, under Lieutenant Colonel Georg Adlersparre marched to Stockholm to depose King Gustav IV. Most of the Norwegians supported the coup, and especially Christian August since he was a candidate to the Swedish throne.[Note 2] On 7 March 1809, Lieutenant Colonel Adlersparre triggered the revolution by raising the flag of rebellion in Karlstad and starting to march upon Stockholm. To prevent the king from joining loyal troops in Scania, seven of the conspirators led by Carl Johan Adlercreutz broke into the royal apartments in the palace on 13 March, seized the king, and imprisoned him and his family in Gripsholm castle. Gustav IV Adolf's uncle, the old, weak and childless Charles XIII, was elected King of Sweden on 5 June, and the next day an assembly of nobles, clergy, bourgeoisie and peasants, passed a constitution.

Fighting in Jämtland

Christian August was very reluctant in the spring and summer of 1809 to make any Norwegian attack against Sweden,[47] but he was eventually pushed to it by King Frederik VI. On 2 July Christian August ordered an attack against Jämtland from Trondheim, and on 10 July a force of 1,800 men, under the leadership of Major General Georg Frederik von Krogh, marched across the border to Jämtland.[48]

To stop the Norwegian advance, Georg Carl von Döbeln was sent out with a battalion of the Hälsinge Regiment to Jemtland, at the same time an additional battalion from Gävle was sent off against Härjedalen and reinforcements later arrived from the Life Grenadier Regiment and the Kalmar Regiment.[49] However, on July 16 the advancing Norwegian army captured the Hjärpe entrenchment which just had been abandoned by a Swedish force of 200 men under Colonel Theodore Nordenadler. Soon afterwards the Norwegians also captured the villages of Mörsil and Mattmar. But when a rumor that Sweden and Russia had started peace negotiations reached the Norwegian army, von Krogh chose to retreat and instead direct his attack against Härjedalen. On July 24, the Swedish force of 900 men under von Döbeln and the 1,800 Norwegian soldiers met at Härjedalen, the Norwegians force was defeated and had to retreat. An armistice was written the following day at Bleckåsen in Alsens.[50] One condition was that all the Norwegian troops would leave Sweden by 3 August, which also happened.[49]

Aftermath

In Norway, the situation steadily worsened due to the British blockade and since they no longer received supplies from northern Russia, after the Russians had made peace with the Swedes on September 17. Sweden's two-front war had also shown to be disastrous for the population and especially the soldiers stationed along the border, due to disease and lack of supplies.[51] It was therefore a desire for peace from both sides, and negotiations began in November.

Treaty of Jönköping

On December 10, 1809 Nils Rosenkrantz and the Swedish Minister Carl Gustaf Adlerberg met in Jönköping to sign the peace treaty between Denmark–Norway and Sweden,[52] which ended the Dano-Swedish War of 1808–1809. Treaty implied the following:

- No country cedes any territory (status quo)

- Sweden tries to keep the British warships in the distance from the Swedish coast

- Renegades and criminals were to be extradited

But Denmark–Norway were still at war with the United Kingdom, and even if Sweden were to make peace with Napoleon in 1810, they were still going to be on the side of the Coalition during the War of the Sixth Coalition. This would further lead to the fact that Norway was ceded to the King of Sweden by the Treaty of Kiel in 1814.

Notes

- Translation of: «[...]intaga den säkraste och fördelaktigaste defensiva ställning mot Norge».

- Christian August was also appointed Crown Prince of Sweden, but since that he died in 1810, the throne went to the French Marschal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte

References

- Ottosen 2012, pp. 12-15

- Jensen 1995, pp. 343-44

- Dyrvik 1999, pp. 206-7

- Högman, Hans. Kriget med Danmark, 1808-1809 (in Swedish). algonet.se. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- Holm 1991, p. 69

- Schnitler 1895, pp. 214-15

- Thyni, Daniel. Skaraborgs regementes historia (in Swedish). skaraborgarna.se. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- Angell 1914, p. 18

- Mykland, Knut. "Christian August". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Oppegaard 1996, pp. 165-66

- Angell 1914, p. 44

- Bratberg, Terje. "Bernhard Ditlef von Staffeldt". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- Saltnes 1998, p. 87-88

- Rastad 1982, p. 18

- Holm 1991, p. 71

- Kongsvinger festnings historie (in Norwegian). forsvarsbygg.no. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- Angell 1914, p. 43

- Angell 1914, p. 53

- Saltnes 1998, pp. 89-90

- Bircka 1889, p. 539

- Angell 1914, p. 85

- Angell 1914, p. 86

- Rastad; Engh & Engen 2004, pp. 10–15

- Högman, Hans. Berömda slag (in Swedish). algonet.se. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- Spett, Stefan. A Vicious Combat in the Norwegian Woods. napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- Bratberg, Terje. "Nicolay Peter Drejer". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- Jensrud, Nils. Slaget ved Trangen (PDF) (in Norwegian). forsvarsforening.no. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- Angell 1914, p. 117

- Olsen 2011, pp. 324-325

- Oppegaard 1996, pp. 168-69

- Angell 1914, pp. 121-122

- Saltnes 1998, pp. 98-99

- Grafsrønningen, Esten. Mobekk, 18. mai 1808 (in Norwegian). elverumske.no. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- Steen 1996, p. 160-62

- Rastad; Engh & Engen 2004, pp. 21-22

- Arnesen, Odd H. Overfallet på Jerpset, 25. mai 1808 (in Norwegian). University of Oslo. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- Ottosen 2012, p. 20

- Holm 1991, p. 107

- Prang, Rainer A. Blodbadet på Prestebakke (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- Koch, Thorbjørn. Det skjedde på Prestebakke, sommeren 1808 (in Norwegian). ostfoldhistorielag.org. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- Angell 1914, pp. 143-144

- Oscarsson, Bo. Hjerpe skans historia (in Swedish). Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- Angell 1914, pp. 156–157

- Oppegaard 1996, p. 175

- Jensen 1995, pp. 353-354

- Alnæs & Hagerud 2009, p. 13

- Högman, Hans. Gustav IV Adolf avsätts (in Swedish). algonet.se. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- Angell 1914, p. 169

- Nordensvan 1898, p. 458-59

- Jensen 1995, p. 355

- Russo-Swedish War. Armed Conflict Events Database. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- Angell 1914, p. 170

Bibliography

- Alnæs, Karsten; Hagerud, Trond (2009). Kongsvingeravtalen, 1809: Spiren til norsk selvstendighet. Kongsvinger: Kongsvinger Festnings venner. ISBN 978-82-996697-6-4.

- Angell, Henrik (1914). Syv-aars-krigen for 17. mai 1807-1814. Kristiania: Aschehoug. ISBN 82-90520-23-9.

- Bircka, Carl Fredrik (1889). "Brandt - Clavus". Dansk biografisk Lexikon. III. Kjøbenhavn: Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag (F. Hegel & Søn).

- Bragstad, Jakob (1996). Fjordane Infanteriregiment, no. 10. Oslo: Elanders Publishing. ISBN 82-90545-57-6.

- Bull, Arne Marensius (2002). Oppland Regiment, 1657-2002. Elverum: Elanders Publishing. ISBN 82-90545-98-3.

- Dyrvik, Ståle (1999). Norsk historie, 1625-1814: vegar til sjølvstende. Oslo: Det norske Samlaget. ISBN 978-82-521-5183-1.

- Ersland, Geir Atle; Holm, Terje H. (2000). Norsk Forsvarshistorie. I. Bergen: Eide forlag. ISBN 82-514-0558-0.

- Gundersen, Børre Reidar (1998). Agder Forsvarsdistrikt/Agder Infanteriregiment, no. 7. Oslo: Elanders Publishing. ISBN 82-90545-82-7.

- Holm, Terje H (1991). "Med Plotons! Høire-sving! Marsch! Marsch!": norsk taktikk og stridsteknikk på begynnelsen av 1800-tallet: med hovedvekt lagt på fotfolket. Oslo: Forsvarsmuseet Akershus-Oslo. ISBN 82-991167-7-5.

- Hodne, Ørnulf (2006). For konge og Fedreland - kvinner og menn i norsk krigshverdag, 1550-1905. Oslo: Cappelen Damm. ISBN 978-82-02-26107-8.

- Jensen, Åke F. (1995). Kavaleriet i Norge, 1200-1994. Oslo: Elanders Publishing. ISBN 82-90545-43-6.

- Jensås, Henry Kristian (2004). Distriktkommando Trøndelag med historisk bakgrunn fra 1628. Trondheim: Tapir Akademiske Forlag. ISBN 82-519-1961-4.

- Nordensvan, Carl Otto (1898). Finska kriget, 1808-1809. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Forlag.

- Olsen, Per Erik (2011). Norges kriger. Oslo: Vega Forlag AS. ISBN 978-82-8211-107-2.

- Oppegaard, Tore Hiorth (1996). Østfold Regiment. Oslo: Elanders Publishing. ISBN 82-90545-59-2.

- Ottosen, Morten Nordhagen (2012). Gustav IV Adolf og Norge, Historisk Tidsskrift 3/2012. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Ottosen, Morten Nordhagen (2012). Popular Responses to Unpopular Wars. Resistance, Collaboration and Experiences in Norwegian Borderlands, 1807-1814. Oslo: University of Oslo.

- Ottosen, Morten Nordhagen, ed. (2012). Samfunn i krig. Norden 1808-09. Oslo: Unipub. ISBN 978-82-7477-557-2.

- Rastad, Per-Erik (1982). Kongsvinger Festnings Historie: Krigsårenen 1807-1814. Kongsvinger: Kongsvinger Festnings venner.

- Rastad, Per-Erik; Engh, Bjørn; Engen, Jorunn (2004). Sju dramatiske år - ufredstid i Glomdalsdistriktet, 1807-1814. Kongsvinger: Kongsvinger Festnings venner.

- Saltnes, Magnar (1998). Akershus Infanteriregiment, no. 4: 1628-1995. Oslo: Elanders Publishing. ISBN 82-90545-78-9.

- Schjølberg, Jacob T. (1988). Telemark Infanteriregiment, no. 3. Oslo: Gyldendal. ISBN 82-90545-09-6.

- Schnitler, Didrik (1895). Blade af Norges krigshistorie. Kristiania: Aschehoug.

- Steen, Ragnar (1996). Den Søndenfieldske Skieløberbattailon i krig og fred: 1747-1826. Oslo: Elanders Publishing. ISBN 82-90545-66-5.

- Sundberg, Ulf (1998). Svenska krig, 1521-1814. Stockholm: Hjalmarson & Högberg. ISBN 91-89080-14-9.