David Gordon Hines

David Gordon Hines (8 February 1915 – 14 March 2000)[1] was a chartered accountant who as a British colonial administrator developed farming co-operatives in Tanganyika and later in Uganda. This radically improved the living standards of farmers in their transition from subsistence farming to cash crops. When he was responsible for development throughout Uganda (with about 400 staff), some 500,000 farmers joined co-operatives.[2]

David Gordon Hines | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) David Hines in King's African Rifles uniform | |

| Born | 8 February 1915 Staffordshire, England |

| Died | 14 March 2000 (aged 85) Bristol, England |

Early life

David Hines was born in Fenton (now part of the potteries town Stoke-on-Trent) in Staffordshire, England on 8 February 1915. His parents lived in Margherita, Assam, India where his father managed coal mines. His grandfather William Hines had founded with his brother the Heron Cross pottery in Stoke-on-Trent. Sadly as a child away from his parents who had to live in Assam, he lived with relations in Barnstaple, and boarded at Blundells School in Tiverton, both in Devon. On retirement of his father, his parents lived in Bushey near London, so David was glad to live with them and be articled in London to the accountants Cooper Brothers, travelling the country for them.

To Kenya

In 1938 he sailed on a Union-Castle liner to Kenya to start work with accountants in Kisumu, only to find that his new firm had just been taken over by his old employers Cooper Brothers. He contracted malaria there like bad flu, with bad sweating — I was in bed for a few days. Only a few years earlier, Kisumu was the white man's grave because of the stagnant water around Lake Victoria. We took care not to paddle in lakes for fear of crocodiles and Bilharzia[3]

World War II

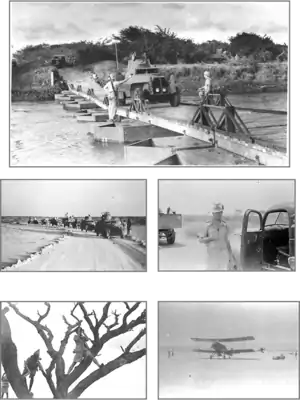

During the Second World War, David Hines served in northern Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Madagascar.

In 1/6 Battalion of the King's African Rifles, he commanded a squadron of 20 light armoured cars which was assigned the task of defending 800 miles (1,300 km) of the northern border of Kenya against a possible Italian invasion from neighbouring Ethiopia. He spent six months with his African crews sharing eating and sleeping under tarpaulins as there were no tents. The working language was Swahili.

At the Outspan Hotel in Kenya, his wife Bertha (Beb) Hines helped Lady Baden-Powell reply to the thousands of letters sent to her on the death in January 1941 of her husband, Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the worldwide Scout movement.

In early 1941, Hines, then a captain, was in the van of General Cunningham's swift 1,900-mile (3,100 km) advance from Kenya to Addis Ababa, via Kismayo and Mogadishu in Somalia and up the one good road through Harar, Dire Dawa, and Awash. With iron rations while advancing in light armoured cars, they captured thousands of Italian troops. They confiscated their arms and many supplies, and left the prisoners for other troops who followed behind. In Addis Ababa, Hines helped rescue numerous Italians and Germans who had surrendered – he saw many others beside the roads who had been crucified by the local Shifta people.

On one occasion, while crossing the River Kolito in Eritrea, David Hines witnessed the heroism of Nigel Gray Leakey (a relative of Louis Leakey, famous for anthropological discoveries in East Africa) that won him the Victoria Cross, the highest British medal for valour.

One night on the Eritrean border, an elephant lost a leg after walking on a landmine defending the camp. At first light, Hines and two askaris tracked the elephant for 20 miles (32 km) before putting it out of its misery.

After taking part in the Allied invasion of Madagascar and being transferred briefly to Burma to fight the Japanese, Hines was made the accountant on the 100,000-acre Tanganyika wheat scheme, set up to help feed war-ravaged Europe.

Tanganyika 1947 to 1959

David Hines was employed in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika (now Tanzania) by the Colonial Office to develop farming co-operatives throughout Tanganyika: even by the early 1950s, there were over 400 co-operatives operational, despite vast areas of central and southern Tanganyika being plagued by Tsetse fly, making them unsuitable for agriculture and cattle raising.[4] Previously, farmers had sold their produce to Indian traders at poor prices. The farmers gained more favourable prices for their crops by banding together in co-operatives and selling their produce in bulk.

Uganda 1959 to 1965

In 1959, Hines became Commissioner of Co-operatives for Uganda reporting to the Governor. He and his staff of 400 advised groups of 100 to 150 farmers on how best to establish a co-operative, defining the constitution and accounting. At meetings he would encourage establishment of co-operatives, listen to farmers' problems, and give speeches to encourage progress.

At a typical initial meeting, he would speak in English with multiple interpreters speaking the local languages. After a while, the meeting would agree to switch to Swahili, despite Ugandans being wary of Swahili, the language used by earlier Arab slavers.[5] Fortunately Hines spoke fluent Swahili.

With government money, the co-operatives built cotton ginneries, tobacco dryers and maize mills – and successfully exported coffee and cotton from this landlocked country. In the three years after Uganda's 1962 independence, David Hines reported to the Uganda Government Minister Matthias Ngobi.

Kenya 1966 to 1972

Hines was seconded by the UK to advise the Kenya Minister of Agriculture particularly about the "Million-acre scheme" to buy expatriate farms mostly in the Kenya highlands.

Retirement

He retired to Kingsdown, near Deal in Kent, England, becoming Treasurer of the Royal Cinque Ports Golf Club.

Three-months 1982 World Bank delegation to devastated Uganda

Due to their years working in Uganda and both speaking Swahili, Hines and a veterinary specialist were surprised to be telephoned by the World Bank to join a delegation of Americans to go to Uganda to "get it started again".[7]

He found that Kampala was appalling: nothing worked; there was no water, no electricity, no sanitation, no food, nothing in the shops. Lifts in a government building did not work: there was automatic gunfire in the street below.

Around the country we had an escort of soldiers. I met some people who I had known … they were delighted to see me. Everybody had lost relatives and friends, and many spoke of torture. On safari north and south, we lived on goats and bananas. Up north, I met an old man who recognised me: he flung himself on the ground and said "You've come back, you've come back". In all the fine hotels, everything had been removed – baths, basins, lavatories – and if you were lucky, someone brought you a tin of hot water to shave.

Following our recommendations, the World Bank brought in money, two accountants, and various agricultural officers and engineers.[8]

Death

David Hines died of prostate cancer in Keynsham Hospital, Bristol on 14 March 2000, leaving two daughters and one son, all born in East Africa.[2]

References

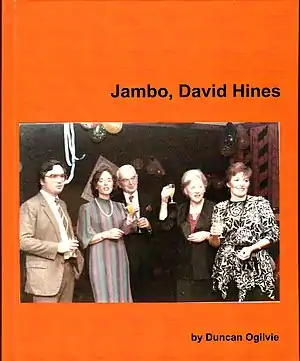

- Book Jambo, David Hines: Swahili for Hello David Hines ISBN 978-1-38-898555-4

- (a) Two-hour interview by WD Ogilvie of David Hines in 1999 (b) Obituary by WD Ogilvie in the London The Daily Telegraph 8 April 2000.

- Book Jambo, David Hines: Swahili for Hello David Hines ISBN 978-1-38-898555-4 page 16

- 3rd edition 1994 Lonely Planet: East Africa ISBN 0-86442-209-1 page 497

- (a) Two-hour interview by WD Ogilvie of David Hines in 1999; (b) Obituary in the London The Daily Telegraph 8 April 2000; (c) Son Peter Gordon Hines.

- Book Jambo, David Hines: Swahili for Hello David Hines ISBN 978-1-38-898555-4

- 978-1-38-898555-4 Jambo David Hines page 55

- All from 978-1-38-898555-4 Jambo David Hines by Duncan Ogilvie, page 55