Swahili language

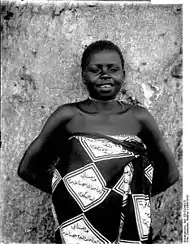

Swahili, also known by its native name Kiswahili, is a Bantu language and the native language of the Swahili people. It is a lingua franca of the African Great Lakes region and other parts of East and Southern Africa, including Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Kenya, some parts of Malawi, Somalia, Zambia, Mozambique, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).[5][6] Comorian, spoken in the Comoros Islands, is sometimes considered a dialect of Swahili, although other authorities consider it a distinct language.[7] Sheng is a mixture of Swahili and English commonly spoken in Kenya and parts of Uganda. Swahili has been greatly influenced by Arabic; there are an enormous number of Arabic loanwords in the language, including the word swahili, from Arabic sawāḥilī (a plural adjectival form of an Arabic word meaning “of the coast”). The language dates from the contacts of Arabian traders with the inhabitants of the east coast of Africa over many centuries. Under Arab influence, Swahili originated as a lingua franca used by several closely related Bantu-speaking tribal groups.[8]

| Swahili | |

|---|---|

| Kiswahili | |

| Pronunciation | [kiswɑˈhili] |

| Native to | Tanzania, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Bajuni Islands (part of Somalia), Mozambique (mostly Mwani), Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya,[1] Comoros, Mayotte, Zambia, Malawi, and Madagascar |

| Ethnicity | Waswahili |

Native speakers | Estimates range from 2 million (2003)[2] to 150 million (2012)[3] L2 speakers: 90 million (1991–2015)[3] |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | sw |

| ISO 639-2 | swa |

| ISO 639-3 | swa – inclusive codeIndividual codes: swc – Congo Swahiliswh – Coastal Swahiliymk – Makwewmw – Mwani |

| Glottolog | swah1254 |

| |

| Linguasphere | 99-AUS-m |

Regions where Swahili is the main language

Regions where Swahili is a second language

Regions where Swahili is an official language but not a majority native language

Regions where Swahili is a minority language | |

| Person | Mswahili |

|---|---|

| People | Waswahili |

| Language | Kiswahili |

The exact number of Swahili speakers, be they native or second-language speakers, is unknown and is a matter of debate. Various estimates have been put forward, which vary widely, ranging from 50 million to 100 million.[9] Swahili serves as a national language of the DRC, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. Shikomor, an official language in Comoros and also spoken in Mayotte (Shimaore), is related to Swahili.[10] Swahili is also one of the working languages of the African Union and officially recognised as a lingua franca of the East African Community.[11] In 2018, South Africa legalized the teaching of Swahili in South African schools as an optional subject to begin in 2020.[12]

Classification

Swahili is a Bantu language of the Sabaki branch.[13] In Guthrie's geographic classification, Swahili is in Bantu zone G, whereas the other Sabaki languages are in zone E70, commonly under the name Nyika. Historical linguists do not consider the Arabic influence on Swahili to be significant enough to classify it as a mixed language, since Arabic influence is limited to lexical items, most of which have been borrowed only since 1500, whereas the grammatical and syntactic structure of the language is typically Bantu.[14][15]

History

Etymology

The origin of the word Swahili is its phonetic equivalent in Arabic: سَاحِل sāħil = "coast", broken plural سَوَاحِل sawāħil = "coasts", سَوَاحِلِىّ sawāħilï = "of coasts".

Origin

The core of the Swahili language originates in Bantu languages of the coast of East Africa. Much of Swahili's Bantu vocabulary has cognates in the Pokomo, Taita and Mijikenda languages[16] and, to a lesser extent, other East African Bantu languages. While opinions vary on the specifics, it has been historically purported that about 20% of the Swahili vocabulary is derived from loan words, the vast majority Arabic, but also other contributing languages, including Persian, Hindustani, Portuguese, and Malay. In the text "Early Swahili History Reconsidered", however, Thomas Spear noted that Swahili retains a large amount of grammar, vocabulary, and sounds inherited from the Sabaki Language. In fact, while taking account of daily vocabulary, using lists of one hundred words, 72-91% were inherited from the Sabaki language (which is reported as a parent language) whereas 4-17% were loan words from other African languages. Only 2-8% were from non-African languages, and Arabic loan words constituted a fraction of the 2-8%.[17] What also remained unconsidered was that a good number of the borrowed terms had native equivalents. The preferred use of Arabic loan words is prevalent along the coast, where natives, in a cultural show of proximity to, or descent from Arab culture, would rather use loan words, whereas the natives in the interior tend to use the native equivalents. It was originally written in Arabic script.[18]

The earliest known documents written in Swahili are letters written in Kilwa,in Tanzania in 1711 in the Arabic script that were sent to the Portuguese of Mozambique and their local allies. The original letters are preserved in the Historical Archives of Goa, India.[19][20]

Colonial period

Various colonial powers that ruled on the coast of East Africa played a role in the growth and spread of Swahili. With the arrival of the Arabs in East Africa, they used Swahili as a language of trade as well as for teaching Islam to the local Bantu peoples. This resulted in Swahili first being written in the Arabic alphabet. The later contact with the Portuguese resulted in the increase of vocabulary of the Swahili language. The language was formalised in an institutional level when the Germans took over after the Berlin conference. After seeing there was already a widespread language, the Germans formalised it as the official language to be used in schools. Thus schools in Swahili are called Shule (from German Schule) in government, trade and the court system. With the Germans controlling the major Swahili-speaking region in East Africa, they changed the alphabet system from Arabic to Latin. After the first World war, Britain took over German East Africa, where they found Swahili rooted in most areas, not just the coastal regions. The British decided to formalise it as the language to be used across the East African region (although in British East Africa [Kenya and Uganda] most areas used English and various Nilotic and other Bantu languages while Swahili was mostly restricted to the coast). In June 1928, an inter-territorial conference attended by representatives of Kenya, Tanganyika, Uganda, and Zanzibar took place in Mombasa. The Zanzibar dialect was chosen as standard Swahili for those areas,[22] and the standard orthography for Swahili was adopted.[23]

Current status

Swahili has become a second language spoken by tens of millions in three African Great Lakes countries (Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania), where it is an official or national language, while being the first language to many people in Tanzania especially in the coastal regions of Tanga, Pwani, Dar es Salaam, Mtwara and Lindi. In the inner regions of Tanzania, Swahili is spoken with an accent influenced by local languages and dialects, and as a first language for most people born in the cities, whilst being spoken as a second language in rural areas. Swahili and closely related languages are spoken by relatively small numbers of people in Burundi, Comoros, Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia and Rwanda.[24] The language was still understood in the southern ports of the Red Sea in the 20th century.[25][26] Swahili speakers may number 120 to 150 million in total.[27]

Swahili is among the first languages in Africa for which language technology applications have been developed. Arvi Hurskainen is one of the early developers. The applications include a spelling checker,[28] part-of-speech tagging,[29] a language learning software,[29] an analysed Swahili text corpus of 25 million words,[30] an electronic dictionary,[29] and machine translation[29] between Swahili and English. The development of language technology also strengthens the position of Swahili as a modern medium of communication.[31]

Tanzania

The widespread use of Swahili as a national language in Tanzania came after Tanganyika gained independence in 1961 and the government decided that it would be used as a language to unify the new nation. This saw the use of Swahili in all levels of government, trade, art as well as schools in which primary school children are taught in Swahili, before switching to English (medium of instruction)[32] of in Secondary schools (although Swahili is still taught as an independent subject) After Tanganyika and Zanzibar unification in 1964, Taasisi ya Uchunguzi wa Kiswahili (TUKI, Institute of Swahili Research) was created from the Interterritorial Language Committee. In 1970 TUKI was merged with the University of Dar es salaam, while Baraza la Kiswahili la Taifa (BAKITA) was formed. BAKITA is an organisation dedicated to the development and advocacy of Swahili as a means of national integration in Tanzania. Key activities mandated for the organization include creating a healthy atmosphere for the development of Swahili, encouraging use of the language in government and business functions, coordinating activities of other organizations involved with Swahili, standardizing the language. BAKITA vision are:1.To efficiently manage and coordinate the development and use of Kiswahili in Tanzania 2.To participate fully and effectively in promoting Swahili in East Africa, Africa and the entire world over.[33] Although other bodies and agencies can propose new vocabularies, BAKITA is the only organisation that can approve its usage in the Swahili language.

Kenya

In Kenya, Chama cha Kiswahili cha Taifa (CHAKITA) was established in 1998 to research and propose means by which Kiswahili can be integrated to a national language and made compulsory in schools the same year.

Religious and political identity

Religion

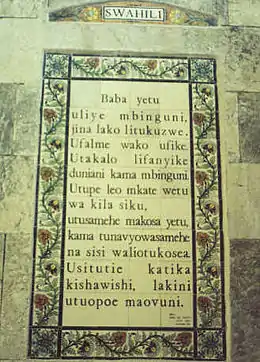

Swahili played a major role in spreading both Christianity and Islam in East Africa. From their arrival in East Africa, Arabs brought Islam and set up madrasas, where they used Swahili to teach Islam to the natives. As the Arab presence grew, more and more natives were converted to Islam and were taught using the Swahili language.

From the arrival of Europeans in East Africa, Christianity was introduced in East Africa. While the Arabs were mostly based in the coastal areas, European missionaries went further inland spreading Christianity. But since the first missionary posts in East Africa were in the coastal areas, missionaries picked up Swahili and used it to spread Christianity since it had a lot of similarities with many of the other indigenous languages in the region.

Politics

During the struggle for Tanganyika independence, the Tanganyika African National Union used Swahili as language of mass organisation and political movement. This included publishing pamphlets and radio broadcasts to rally the people to fight for independence. After independence, Swahili was adopted as the national language of the nation. Till this day, Tanzanians carry a sense of pride when it comes to Swahili especially when it is used to unite over 120 tribes across Tanzania. Swahili was used to strengthen solidarity among the people and a sense of togetherness and for that Swahili remains a key identity of the Tanzanian people.

Phonology

Vowels

Standard Swahili has five vowel phonemes: /ɑ/, /ɛ/, /i/, /ɔ/, and /u/. According to Ellen Contini-Morava, vowels are never reduced, regardless of stress.[34] However, according to Edgar Polomé, these five phonemes can vary in pronunciation. Polomé claims that /ɛ/, /i/, /ɔ/, and /u/ are pronounced as such only in stressed syllables. In unstressed syllables, as well as before a prenasalized consonant, they are pronounced as /e/, /ɪ/, /o/, and /ʊ/. E is also commonly pronounced as mid-position after w. Polomé claims that /ɑ/ is pronounced as such only after w and is pronounced as [a] in other situations, especially after /j/ (y). A can be pronounced as [ə] in word-final position.[35] Swahili vowels can be long; these are written as two vowels (example: kondoo, meaning "sheep"). This is due to a historical process in which the L became deleted between two examples of the same vowel (kondoo was originally pronounced kondolo, which survives in certain dialects). However, these long vowels are not considered to be phonemic. A similar process exists in Zulu.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar / Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ɲ ⟨ny⟩ | ŋ ⟨ng'⟩ | |||

| Stop | prenasalized | mb̥ ⟨mb⟩ | nd̥ ⟨nd⟩ | nd̥ʒ̊ ⟨nj⟩ | ŋɡ̊ ⟨ng⟩ | ||

| implosive / voiced |

ɓ ~ b ⟨b⟩ | ɗ ~ d ⟨d⟩ | ʄ ~ dʒ ⟨j⟩ | ɠ ~ ɡ ⟨g⟩ | |||

| voiceless | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | tʃ ⟨ch⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | |||

| aspirated | (pʰ ⟨p⟩) | (tʰ ⟨t⟩) | (tʃʰ ⟨ch⟩) | (kʰ ⟨k⟩) | |||

| Fricative | prenasalized | mv̥ ⟨mv⟩ | nz̥ ⟨nz⟩ | ||||

| voiced | v ⟨v⟩ | (ð ⟨dh⟩) | z ⟨z⟩ | (ɣ ⟨gh⟩) | |||

| voiceless | f ⟨f⟩ | (θ ⟨th⟩) | s ⟨s⟩ | ʃ ⟨sh⟩ | (x ⟨kh⟩) | h ⟨h⟩ | |

| Approximant | l ⟨l⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | w ⟨w⟩ | ||||

| Rhotic | r ⟨r⟩ | ||||||

Some dialects of Swahili may also have the aspirated phonemes /pʰ tʰ tʃʰ kʰ bʱ dʱ dʒʱ ɡʱ/ though they are unmarked in Swahili's orthography.[37] Multiple studies favour classifying prenasalization as consonant clusters, not as separate phonemes. Historically, nasalization has been lost before voiceless consonants, and subsequently the voiced consonants have devoiced, though they are still written mb, nd etc. The /r/ phoneme is realised as either a short trill [r] or more commonly as a single tap [ɾ] by most speakers. [x] exists in free variation with h, and is only distinguished by some speakers.[35] In some Arabic loans (nouns, verbs, adjectives), emphasis or intensity is expressed by reproducing the original emphatic consonants /dˤ, sˤ, tˤ, zˤ/ and the uvular /q/, or lengthening a vowel, where aspiration would be used in inherited Bantu words.[38]

Orthography

Swahili is now written in the Latin alphabet. There are a few digraphs for native sounds, ch, sh, ng and ny; q and x are not used,[39] c is not used apart from the digraph ch, unassimilated English loans and, occasionally, as a substitute for k in advertisements. There are also several digraphs for Arabic sounds, which many speakers outside of ethnic Swahili areas have trouble differentiating.

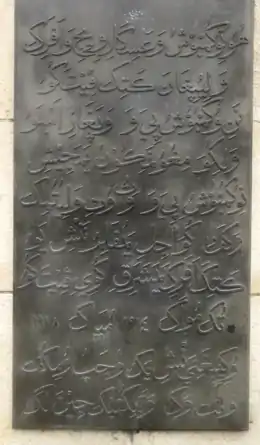

The language used to be written in the Arabic script. Unlike adaptations of the Arabic script for other languages, relatively little accommodation was made for Swahili. There were also differences in orthographic conventions between cities and authors and over the centuries, some quite precise but others different enough to cause difficulties with intelligibility.

/e/ and /i/, and /o/ and /u/ were often conflated, but in some spellings, /e/ was distinguished from /i/ by rotating the kasra 90° and /o/ was distinguished from /u/ by writing the damma backwards.

Several Swahili consonants do not have equivalents in Arabic, and for them, often no special letters were created unlike, for example, Urdu script. Instead, the closest Arabic sound is substituted. Not only did that mean that one letter often stands for more than one sound, but also writers made different choices of which consonant to substitute. Here are some of the equivalents between Arabic Swahili and Roman Swahili:

| Swahili in Arabic Script | Swahili in Latin Alphabet | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final | Medial | Initial | Isolated | |

| ـا | ا | aa | ||

| ـب | ـبـ | بـ | ب | b p mb mp bw pw mbw mpw |

| ـت | ـتـ | تـ | ت | t nt |

| ـث | ـثـ | ثـ | ث | th? |

| ـج | ـجـ | جـ | ج | j nj ng ng' ny |

| ـح | ـحـ | حـ | ح | h |

| ـخ | ـخـ | خـ | خ | kh h |

| ـد | د | d nd | ||

| ـذ | ذ | dh? | ||

| ـر | ر | r d nd | ||

| ـز | ز | z nz | ||

| ـس | ـسـ | سـ | س | s |

| ـش | ـشـ | شـ | ش | sh ch |

| ـص | ـصـ | صـ | ص | s, sw |

| ـض | ـضـ | ضـ | ض | dhw |

| ـط | ـطـ | طـ | ط | t tw chw |

| ـظ | ـظـ | ظـ | ظ | z th dh dhw |

| ـع | ـعـ | عـ | ع | ? |

| ـغ | ـغـ | غـ | غ | gh g ng ng' |

| ـف | ـفـ | فـ | ف | f fy v vy mv p |

| ـق | ـقـ | قـ | ق | k g ng ch sh ny |

| ـك | ـكـ | كـ | ك | |

| ـل | ـلـ | لـ | ل | l |

| ـم | ـمـ | مـ | م | m |

| ـن | ـنـ | نـ | ن | n |

| ـه | ـهـ | هـ | ه | h |

| ـو | و | w | ||

| ـي | ـيـ | يـ | ي | y ny |

That was the general situation, but conventions from Urdu were adopted by some authors so as to distinguish aspiration and /p/ from /b/: پھا /pʰaa/ 'gazelle', پا /paa/ 'roof'. Although it is not found in Standard Swahili today, there is a distinction between dental and alveolar consonants in some dialects, which is reflected in some orthographies, for example in كُٹَ -kuta 'to meet' vs. كُتَ -kut̠a 'to be satisfied'. A k with the dots of y, ـػـػـػـػ, was used for ch in some conventions; ky being historically and even contemporaneously a more accurate transcription than Roman ch. In Mombasa, it was common to use the Arabic emphatics for Cw, for example in صِصِ swiswi (standard sisi) 'we' and كِطَ kit̠wa (standard kichwa) 'head'.

Particles such as ya, na, si, kwa, ni are joined to the following noun, and possessives such as yangu and yako are joined to the preceding noun, but verbs are written as two words, with the subject and tense–aspect–mood morphemes separated from the object and root, as in aliyeniambia "he who told me".[40]

Grammar

Noun classes

Swahili nouns are separable into classes, which are roughly analogous to genders in other languages. For example, just as suffix <-o> in Spanish and Italian marks masculine objects, and <-a> marks feminine ones, so, in Swahili, prefixes mark groups of similar objects: <m-> marks single human beings (mtoto 'child'), <wa-> marks multiple humans (watoto 'children'), <u-> marks abstract nouns (utoto 'childhood'), and so on. And just as adjectives and pronouns must agree with the gender of nouns in Spanish and Italian, so in Swahili adjectives, pronouns and even verbs must agree with nouns. This is a characteristic feature of all the Bantu languages, and traces of it are found in many of the other branches of the Niger-Congo language family in West Africa.

Semantic motivation

The ki-/vi- class historically consisted of two separate genders, artefacts (Bantu class 7/8, utensils and hand tools mostly) and diminutives (Bantu class 12/13), which were conflated at a stage ancestral to Swahili. Examples of the former are kisu "knife", kiti "chair" (from mti "tree, wood"), chombo "vessel" (a contraction of ki-ombo). Examples of the latter are kitoto "infant", from mtoto "child"; kitawi "frond", from tawi "branch"; and chumba (ki-umba) "room", from nyumba "house". It is the diminutive sense that has been furthest extended. An extension common to diminutives in many languages is approximation and resemblance (having a 'little bit' of some characteristic, like -y or -ish in English). For example, there is kijani "green", from jani "leaf" (compare English 'leafy'), kichaka "bush" from chaka "clump", and kivuli "shadow" from uvuli "shade". A 'little bit' of a verb would be an instance of an action, and such instantiations (usually not very active ones) are found: kifo "death", from the verb -fa "to die"; kiota "nest" from -ota "to brood"; chakula "food" from kula "to eat"; kivuko "a ford, a pass" from -vuka "to cross"; and kilimia "the Pleiades", from -limia "to farm with", from its role in guiding planting. A resemblance, or being a bit like something, implies marginal status in a category, so things that are marginal examples of their class may take the ki-/vi- prefixes. One example is chura (ki-ura) "frog", which is only half terrestrial and therefore is marginal as an animal. This extension may account for disabilities as well: kilema "a cripple", kipofu "a blind person", kiziwi "a deaf person". Finally, diminutives often denote contempt, and contempt is sometimes expressed against things that are dangerous. This might be the historical explanation for kifaru "rhinoceros", kingugwa "spotted hyena", and kiboko "hippopotamus" (perhaps originally meaning "stubby legs").

Another class with broad semantic extension is the m-/mi- class (Bantu classes 3/4). This is often called the 'tree' class, because mti, miti "tree(s)" is the prototypical example. However, it seems to cover vital entities neither human nor typical animals: trees and other plants, such as mwitu 'forest' and mtama 'millet' (and from there, things made from plants, like mkeka 'mat'); supernatural and natural forces, such as mwezi 'moon', mlima 'mountain', mto 'river'; active things, such as moto 'fire', including active body parts (moyo 'heart', mkono 'hand, arm'); and human groups, which are vital but not themselves human, such as mji 'village', and, by analogy, mzinga 'beehive/cannon'. From the central idea of tree, which is thin, tall, and spreading, comes an extension to other long or extended things or parts of things, such as mwavuli 'umbrella', moshi 'smoke', msumari 'nail'; and from activity there even come active instantiations of verbs, such as mfuo "metal forging", from -fua "to forge", or mlio "a sound", from -lia "to make a sound". Words may be connected to their class by more than one metaphor. For example, mkono is an active body part, and mto is an active natural force, but they are also both long and thin. Things with a trajectory, such as mpaka 'border' and mwendo 'journey', are classified with long thin things, as in many other languages with noun classes. This may be further extended to anything dealing with time, such as mwaka 'year' and perhaps mshahara 'wages'. Animals exceptional in some way and so not easily fitting in the other classes may be placed in this class.

The other classes have foundations that may at first seem similarly counterintuitive.[41] In short,

- Classes 1–2 include most words for people: kin terms, professions, ethnicities, etc., including translations of most English words ending in -er. They include a couple of generic words for animals: mnyama 'beast', mdudu 'bug'.

- Classes 5–6 have a broad semantic range of groups, expanses, and augmentatives. Although interrelated, it is easier to illustrate if broken down:

- Augmentatives, such as joka 'serpent' from nyoka 'snake', lead to titles and other terms of respect (the opposite of diminutives, which lead to terms of contempt): Bwana 'Sir', shangazi 'aunt', fundi 'craftsman', kadhi 'judge'

- Expanses: ziwa 'lake', bonde 'valley', taifa 'country', anga 'sky'

- from this, mass nouns: maji 'water', vumbi 'dust' (and other liquids and fine particulates that may cover broad expanses), kaa 'charcoal', mali 'wealth', maridhawa 'abundance'

- Collectives: kundi 'group', kabila 'language/ethnic group', jeshi 'army', daraja ' stairs', manyoya 'fur, feathers', mapesa 'small change', manyasi 'weeds', jongoo 'millipede' (large set of legs), marimba 'xylophone' (large set of keys)

- from this, individual things found in groups: jiwe 'stone', tawi 'branch', ua 'flower', tunda 'fruit' (also the names of most fruits), yai 'egg', mapacha 'twins', jino 'tooth', tumbo 'stomach' (cf. English "guts"), and paired body parts such as jicho 'eye', bawa 'wing', etc.

- also collective or dialogic actions, which occur among groups of people: neno 'a word', from kunena 'to speak' (and by extension, mental verbal processes: wazo 'thought', maana 'meaning'); pigo 'a stroke, blow', from kupiga 'to hit'; gomvi 'a quarrel', shauri 'advice, plan', kosa 'mistake', jambo 'affair', penzi 'love', jibu 'answer', agano 'promise', malipo 'payment'

- From pairing, reproduction is suggested as another extension (fruit, egg, testicle, flower, twins, etc.), but these generally duplicate one or more of the subcategories above

- Classes 9–10 are used for most typical animals: ndege 'bird', samaki 'fish', and the specific names of typical beasts, birds, and bugs. However, this is the 'other' class, for words not fitting well elsewhere, and about half of the class 9–10 nouns are foreign loanwords. Loans may be classified as 9–10 because they lack the prefixes inherent in other classes, and most native class 9–10 nouns have no prefix. Thus they do not form a coherent semantic class, though there are still semantic extensions from individual words.

- Class 11 (which takes class 10 for the plural) are mostly nouns with an "extended outline shape", in either one dimension or two:

- mass nouns that are generally localized rather than covering vast expanses: uji 'porridge', wali 'cooked rice'

- broad: ukuta 'wall', ukucha 'fingernail', upande 'side' (≈ ubavu 'rib'), wavu 'net', wayo 'sole, footprint', ua 'fence, yard', uteo 'winnowing basket'

- long: utambi 'wick', utepe 'stripe', uta 'bow', ubavu 'rib', ufa 'crack', unywele 'a hair'

- from 'a hair', singulatives of nouns, which are often class 6 ('collectives') in the plural: unyoya 'a feather', uvumbi 'a grain of dust', ushanga 'a bead'.

- Class 14 are abstractions, such as utoto 'childhood' (from mtoto 'a child') and have no plural. They have the same prefixes and concord as class 11, except optionally for adjectival concord.

- Class 15 are verbal infinitives.

- Classes 16–18 are locatives. The Bantu nouns of these classes have been lost; the only permanent member is the Arabic loan mahali 'place(s)', but in Mombasa Swahili, the old prefixes survive: pahali 'place', mwahali 'places'. However, any noun with the locative suffix -ni takes class 16–18 agreement. The distinction between them is that class 16 agreement is used if the location is intended to be definite ("at"), class 17 if indefinite ("around") or involves motion ("to, toward"), and class 18 if it involves containment ("within"): mahali pazuri 'a good spot', mahali kuzuri 'a nice area', mahali muzuri (it's nice in there).

Borrowing

Borrowings may or may not be given a prefix corresponding to the semantic class they fall in. For example, Arabic دود dūd ("bug, insect") was borrowed as mdudu, plural wadudu, with the class 1/2 prefixes m- and wa-, but Arabic فلوس fulūs ("fish scales", plural of فلس fals) and English sloth were borrowed as simply fulusi ("mahi-mahi" fish) and slothi ("sloth"), with no prefix associated with animals (whether those of class 9/10 or 1/2).

In the process of naturalization[42] of borrowings within Swahili, loanwords are often reinterpreted, or reanalysed,[43] as if they already contain a Swahili class prefix. In such cases the interpreted prefix is changed with the usual rules. Consider the following loanwords from Arabic:

- The Swahili word for "book", kitabu, is borrowed from Arabic كتاب kitāb(un) "book" (plural كتب kutub; from the Arabic root k.t.b. "write"). However, the Swahili plural form of this word ("books") is vitabu, following Bantu grammar in which the ki- of kitabu is reanalysed (reinterpreted) as a nominal class prefix whose plural is vi- (class 7/8).[43]

- Arabic معلم muʿallim(un) ("teacher", plural معلمين muʿallimīna) was interpreted as having the mw- prefix of class 1, and so became mwalimu, plural walimu.

- Arabic مدرسة madrasa school, even though it is singular in Arabic (with plural مدارس madāris), was reinterpreted as a class 6 plural madarasa, receiving the singular form darasa.

Similarly, English wire and Arabic وقت waqt ("time") were interpreted as having the class 11 prevocalic prefix w-, and became waya and wakati with plural nyaya and nyakati respectively.

Agreement

Swahili phrases agree with nouns in a system of concord but, if the noun refers to a human, they accord with noun classes 1–2 regardless of their noun class. Verbs agree with the noun class of their subjects and objects; adjectives, prepositions and demonstratives agree with the noun class of their nouns. In Standard Swahili (Kiswahili sanifu), based on the dialect spoken in Zanzibar, the system is rather complex; however, it is drastically simplified in many local variants where Swahili is not a native language, such as in Nairobi. In non-native Swahili, concord reflects only animacy: human subjects and objects trigger a-, wa- and m-, wa- in verbal concord, while non-human subjects and objects of whatever class trigger i-, zi-. Infinitives vary between standard ku- and reduced i-.[44] ("Of" is animate wa and inanimate ya, za.)

In Standard Swahili, human subjects and objects of whatever class trigger animacy concord in a-, wa- and m-, wa-, and non-human subjects and objects trigger a variety of gender-concord prefixes.

| NC | Semantic field | Noun -C, -V | Subj. | Obj. | -a | Adjective -C, -i, -e[* 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | I | (mimi) | ni- | |||

| – | we | (sisi) | tu- | |||

| – | thou | (wewe) | u- | ku- | ||

| – | you | (ninyi) | m- | wa- | ||

| 1 | person | m-, mw- | a- | m- | wa | m-, mwi-, mwe- |

| 2 | people | wa-, w- | wa- | wa | wa-, we-, we- | |

| 3 | tree | m- | u- | wa | m-, mwi-, mwe- | |

| 4 | trees | mi- | i- | ya | mi-, mi-, mye- | |

| 5 | group, AUG | ji-/Ø, j- | li- | la | ji-/Ø, ji-, je- | |

| 6 | groups, AUG | ma- | ya- | ya | ma-, me-, me- | |

| 7 | tool, DIM | ki-, ch- | ki- | cha | ki-, ki-, che- | |

| 8 | tools, DIM | vi-, vy- | vi- | vya | vi-, vi-, vye- | |

| 9 | animals, 'other', loanwords |

N- | i- | ya | N-, nyi-, nye- | |

| 10 | zi- | za | ||||

| 11 | extension | u-, w-/uw- | u- | wa | m-, mwi-, mwe- | |

| 10 | (plural of 11) | N- | zi- | za | N-, nyi-, nye- | |

| 14 | abstraction | u-, w-/uw- | u- | wa | m-, mwi-, mwe- or u-, wi-, we- | |

| 15 | infinitives | ku-, kw-[* 2] | ku- | kwa- | ku-, kwi-, kwe- | |

| 16 | position | -ni, mahali | pa- | pa | pa-, pe-, pe- | |

| 17 | direction, around | -ni | ku- | kwa | ku-, kwi-, kwe- | |

| 18 | within, along | -ni | mu- | (NA) | mwa | mu-, mwi-, mwe- |

- Most Swahili adjectives begin with either a consonant or the vowels i- or e-, listed separately above. The few adjectives beginning with other vowels do not agree with all noun classes since some are restricted to humans. NC 1 m(w)- is mw- before a and o, and reduces to m- before u; wa- does not change; and ki-, vi-, mi- become ch-, vy-, my- before o but not before u: mwanana, waanana "gentle", mwororo, waororo, myororo, chororo, vyororo "mild, yielding", mume, waume, kiume, viume "male".

- In a few verbs: kwenda, kwisha

Dialects and closely related languages

This list is based on Swahili and Sabaki: a linguistic history.

Dialects

Modern standard Swahili is based on Kiunguja, the dialect spoken in Zanzibar Town, but there are numerous dialects of Swahili, some of which are mutually unintelligible, such as the following:[45]

Old dialects

Maho (2009) considers these to be distinct languages:

- Kimwani is spoken in the Kerimba Islands and northern coastal Mozambique.

- Chimwiini is spoken by the ethnic minorities in and around the town of Barawa on the southern coast of Somalia.

- Kibajuni is spoken by the Bajuni minority ethnic group on the coast and islands on both sides of the Somali–Kenyan border and in the Bajuni Islands (the northern part of the Lamu archipelago) and is also called Kitikuu and Kigunya.

- Socotra Swahili (extinct)

- Sidi, in Gujarat (extinct)

The rest of the dialects are divided by him into two groups:

- Mombasa–Lamu Swahili

- Lamu

- Kiamu is spoken in and around the island of Lamu (Amu).

- Kipate is a local dialect of Pate Island, considered to be closest to the original dialect of Kingozi.

- Kingozi is an ancient dialect spoken on the Indian Ocean coast between Lamu and Somalia and is sometimes still used in poetry. It is often considered the source of Swahili.

- Mombasa

- Chijomvu is a subdialect of the Mombasa area.

- Kimvita is the major dialect of Mombasa (also known as "Mvita", which means "war", in reference to the many wars which were fought over it), the other major dialect alongside Kiunguja.

- Kingare is the subdialect of the Mombasa area.

- Kimrima is spoken around Pangani, Vanga, Dar es Salaam, Rufiji and Mafia Island.

- Kiunguja is spoken in Zanzibar City and environs on Unguja (Zanzibar) Island. Kitumbatu (Pemba) dialects occupy the bulk of the island.

- Mambrui, Malindi

- Chichifundi, a dialect of the southern Kenya coast.

- Chwaka

- Kivumba, a dialect of the southern Kenya coast.

- Nosse Be (Madagascar)

- Lamu

- Pemba Swahili

- Kipemba is a local dialect of the Pemba Island.

- Kitumbatu and Kimakunduchi are the countryside dialects of the island of Zanzibar. Kimakunduchi is a recent renaming of "Kihadimu"; the old name means "serf" and so is considered pejorative.

- Makunduchi

- Mafia, Mbwera

- Kilwa (extinct)

- Kimgao used to be spoken around Kilwa District and to the south.

Maho includes the various Comorian dialects as a third group. Most other authorities consider Comorian to be a Sabaki language, distinct from Swahili.[46]

Other regions

In Somalia, where the Afroasiatic Somali language predominates, a variant of Swahili referred to as Chimwiini (also known as Chimbalazi) is spoken along the Benadir coast by the Bravanese people.[47] Another Swahili dialect known as Kibajuni also serves as the mother tongue of the Bajuni minority ethnic group, which lives in the tiny Bajuni Islands as well as the southern Kismayo region.[47][48]

In Oman, there are an estimated 22,000 people who speak Swahili.[49] Most are descendants of those repatriated after the fall of the Sultanate of Zanzibar.[50][51]

Swahili poets

- Shaaban bin Robert

- Mathias E. Mnyampala

- Euphrase Kezilahabi

- Fadhy Mtanga

- Christopher Mwashinga

- Tumi Molekane

- Dotto Rangimoto

- Mohammed Ghassani

- Sayyid Abdallah

References

- Thomas J. Hinnebusch, 1992, "Swahili", International Encyclopedia of Linguistics, Oxford, pp. 99–106

David Dalby, 1999/2000, The Linguasphere Register of the World's Languages and Speech Communities, Linguasphere Press, Volume Two, pp. 733–735

Benji Wald, 1994, "Sub-Saharan Africa", Atlas of the World's Languages, Routledge, pp. 289–346, maps 80, 81, 85 - Hinnebusch, Thomas J. (2003). "Swahili". In William J. Frawley (ed.). International Encyclopedia of Linguistics (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195139778.

First-language (L1) speakers of Swahili, who probably number no more than two million

- Swahili at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

Congo Swahili at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

Coastal Swahili at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

Makwe at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

Mwani at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018) - Jouni Filip Maho, 2009. New Updated Guthrie List Online

- Mazrui, Ali Al'Amin. (1995). Swahili state and society : the political economy of an African language. East African Educational Publishers. ISBN 0-85255-729-9. OCLC 441402890.

- Prins 1961

- Nurse and Hinnebusch, 1993, p.18

- "Swahili language". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "HOME – Home". Swahililanguage.stanford.edu. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

After Arabic, Swahili is the most widely used African language but the number of its speakers is another area in which there is little agreement. The most commonly mentioned numbers are 50, 80, and 100 million people. [...] The number of its native speakers has been placed at just under 20 million.

- Nurse and Hinnebusch, 1993

- "Development and Promotion of Extractive Industries and Mineral Value Addition". East African Community.

- Sobuwa, Yoliswa (17 September 2018). "Kiswahili gets minister's stamp to be taught in SA schools". The Sowetan.

- Derek Nurse, Thomas J. Hinnebusch, Gérard Philippson. 1993. Swahili and Sabaki: A Linguistic History. University of California Press

- Derek Nurse, Thomas T. Spear. 1985. Arabic loan words make up to 20% of the language. The Swahili: Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society, 800–1500. University of Pennsylvania Press

- Thomas Spear. 2000. "Early Swahili History Reconsidered". The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 257–290

- Polomé, Edgar (1967). Swahili Language Handbook (PDF). Centre for Applied Linguistics. p. 28.

- Spear, Thomas (2000). "Early Swahili History Reconsidered". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 33 (2): 257–290. doi:10.2307/220649. JSTOR 220649.

- Juma, Abdurahman. "Swahili history". glcom.com. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- Alpers, E. A. (1975). Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa. London. pp. 98–99.

- Vernet, T. (2002). "Les cités-Etats swahili et la puissance omanaise (1650–1720)". Journal des Africanistes. 72 (2): 102–05. doi:10.3406/jafr.2002.1308.

- "Baba yetu". Wikisource. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Swahili". About World Languages.

- Mdee, James S. (1999). "Dictionaries and the Standardization of Spelling in Swahili". Lexikos. pp. 126–27. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- Nurse & Thomas Spear (1985) The Swahili

- Kharusi, N. S. (2012). "The ethnic label Zinjibari: Politics and language choice implications among Swahili speakers in Oman". Ethnicities. 12 (3): 335–353. doi:10.1177/1468796811432681. S2CID 145808915.

- Adriaan Hendrik Johan Prins (1961) The Swahili-speaking Peoples of Zanzibar and the East African Coast. (Ethnologue)

- (2005 World Bank Data).

- "Zana za Uhakiki za Microsoft Office 2016 - Kiingereza". Microsoft Download Center. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Salama". 77.240.23.241. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Helsinki Corpus of Swahili 2.0 (HCS 2.0) – META-SHARE". metashare.csc.fi. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Hurskainen, Arvi. 2018. Sustainable language technology for African languages. In Agwuele, Augustine and Bodomo, Adams (eds), The Routledge Handbook of African Linguistics, 359–375. London: Routledge Publishers. ISBN 978-1-138-22829-0

- The Failure of Language Policy in Tanzanian Schools

- https://www.bakita.go.tz/eng/vision_mission

- Contini-Morava, Ellen. 1997. Swahili Phonology. In Kaye, Alan S. (ed.), Phonologies of Asia and Africa 2, 841–860. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

- https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED012888.pdf

- Modern Swahili Grammar East African Publishers, 2001 Mohamed Abdulla Mohamed p. 4

- https://web.archive.org/web/20200715041859/https://sprak.gu.se/digitalAssets/1324/1324063_aspiration-in-swahili.pdf

- https://sprak.gu.se/digitalAssets/1324/1324063_aspiration-in-swahili.pdf, p. 157.

- "A Guide to Swahili – The Swahili alphabet". BBC.

- Jan Knappert (1971) Swahili Islamic poetry, Volume 1

- See Contini-Morava for details.

- See pp. 83-84 in Ghil'ad Zuckermann (2020), Revivalistics: From the Genesis of Israeli to Language Reclamation in Australia and Beyond, Oxford University Press ISBN 9780199812790 / ISBN 9780199812776.

- See pp. 11 and 52 in Ghil'ad Zuckermann (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew, Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 9781403917232 / ISBN 9781403938695.

- Kamil Ud Deen, 2005. The acquisition of Swahili.

- H.E.Lambert 1956, 1957, 1958

- Derek Nurse; Thomas Spear; Thomas T. Spear (1985). The Swahili: Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society, 800–1500. p. 65. ISBN 9780812212075.

- "Somalia". Ethnologue. 19 February 1999. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2007). Kenya: identity of a nation. New Africa Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-9802587-9-0.

- "Oman". Ethnologue. 19 February 1999. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Fuchs, Martina (5 October 2011). "African Swahili music lives on in Oman". Reuters. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Beate Ursula Josephi, Journalism education in countries with limited media freedom, Volume 1 of Mass Communication and Journalism, (Peter Lang: 2010), p.96.

Sources

- Ashton, E. O. Swahili Grammar: Including intonation. Longman House. Essex 1947. ISBN 0-582-62701-X.

- Irele, Abiola and Biodun Jeyifo. The Oxford encyclopedia of African thought, Volume 1. Oxford University Press US. New York City. 2010. ISBN 0-19-533473-6

- Blommaert, Jan: Situating language rights: English and Swahili in Tanzania revisited (sociolinguistic developments in Tanzanian Swahili) – Working Papers in Urban Language & Literacies, paper 23, University of Gent 2003

- Brock-Utne, Birgit (2001). "Education for all – in whose language?". Oxford Review of Education. 27 (1): 115–134. doi:10.1080/03054980125577. S2CID 144457326.

- Chiraghdin, Shihabuddin and Mathias E. Mnyampala. Historia ya Kiswahili. Oxford University Press. Eastern Africa. 1977. ISBN 0-19-572367-8

- Contini-Morava, Ellen. Noun Classification in Swahili. 1994.

- Lambert, H.E. 1956. Chi-Chifundi: A Dialect of the Southern Kenya Coast. (Kampala)

- Lambert, H.E. 1957. Ki-Vumba: A Dialect of the Southern Kenya Coast. (Kampala)

- Lambert, H.E. 1958. Chi-Jomvu and ki-Ngare: Subdialects of the Mombasa Area. (Kampala)

- Marshad, Hassan A. Kiswahili au Kiingereza (Nchini Kenya). Jomo Kenyatta Foundation. Nairobi 1993. ISBN 9966-22-098-4.

- Nurse, Derek, and Hinnebusch, Thomas J. Swahili and Sabaki: a linguistic history. 1993. Series: University of California Publications in Linguistics, v. 121.

- Ogechi, Nathan Oyori: "On language rights in Kenya (on the legal position of Swahili in Kenya)", in: Nordic Journal of African Studies 12(3): 277–295 (2003)

- Prins, A.H.J. 1961. "The Swahili-Speaking Peoples of Zanzibar and the East African Coast (Arabs, Shirazi and Swahili)". Ethnographic Survey of Africa, edited by Daryll Forde. London: International African Institute.

- Prins, A.H.J. 1970. A Swahili Nautical Dictionary. Preliminary Studies in Swahili Lexicon – 1. Dar es Salaam.

- Sakai, Yuko. 2020. Swahili Syntax Tree Diagram: Based on Universal Sentence Structure. Createspace. ISBN 978-1696306461

- Whiteley, Wilfred. 1969. Swahili: the rise of a national language. London: Methuen. Series: Studies in African History.

External links

| Swahili edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- UCLA report on Swahili

- John Ogwana (2001) Swahili Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow: Factors of Its Development and Expansion

- List of Swahili Dictionaries

- Arthur Cornwallis Madan (1902). English-Swahili dictionary. archive.org. Clarendon Press. p. 555. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018.