De Bono's invasion of Abyssinia

De Bono's invasion of Abyssinia took place during the opening stages of the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. Italian General Emilio De Bono invaded northern Abyssinia from staging areas in the Italian colony of Eritrea on what was known as the "northern front."

| De Bono's invasion of Abyssinia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Italo-Abyssinian War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 125,000 | 15,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | 1,200 captured | ||||||

Background

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini had long held a desire for a new Italian Empire. Reminiscent of the Roman Empire, Mussolini's new empire was to rule over the Mediterranean and North Africa. His new empire would also avenge past Italian defeats. Chief among these defeats was the Battle of Adwa which took place in Abyssinia on 1 March 1896. Mussolini promised the Italian people "a place in the sun", matching the extensive colonial empires of Britain and France.

Ethiopia was a prime candidate of this expansionist goal for several reasons. Following the Scramble for Africa by the European imperialists, it was one of the few remaining independent African nations. Acquiring Ethiopia would serve to unify Italian-held Eritrea and Italian Somaliland. In addition, Ethiopia was considered to be militarily weak and rich in resources.

In November 1932, per a request from Mussolini, De Bono wrote up a plan for an invasion of Ethiopia. What he wrote indicated that he envisioned a traditional mode of penetration. A limited force would move gradually southward from Eritrea. The force would establish bases of strength and, from these bases, advance against increasingly weakened and disorganized opponents. The invasion DeBono envisioned would be cheap, easy, safe and slow.[1]

Italian invasion

At precisely 5:00 am on 3 October 1935, General Emilio De Bono crossed the Mareb River and advanced into Ethiopia from Eritrea without a Declaration of War.[2] In response to the Italian invasion, Ethiopia declared war on Italy.[3] At this point in the campaign, roadways represented a serious drawback for the Italians as they crossed into Ethiopia. On the Italian side, roads had been constructed right up to the border. On the Ethiopian side, these roads often transitioned into vaguely defined paths.[2]

General Emilio De Bono was the Commander-in-Chief of all Italian armed forces in East Africa. In addition, he was the Commander-in-Chief of the forces invading from Eritrea, the "northern front." De Bono had under his direct command a force of nine divisions in three Army Corps: The Italian I Corps, the Italian II Corps, and the Eritrean Corps.

General Rodolfo Graziani was De Bono's subordinate. He was the Commander-in-Chief of forces invading from Italian Somaliland, the "southern front." Initially he had two divisions and a variety of smaller units under his command. Soon after De Bono advanced from Eritrea, Graziani would advance into Ethiopia from Somaliland with a force of Italians, Somalis, Eritreans, and Libyans.

Adigrat and Adwa

On 5 October, the I Corps took Adigrat and, by 6 October 1935, Adwa[4] was captured by the II Corps. In 1896, Adwa was the site of a humiliating Italian defeat during the First Italo–Ethiopian War and now that historic defeat was "avenged." But, in 1935, the Italian capture of Adwa was accomplished with almost no Ethiopian resistance. Haile Selassie had ordered Ras[nb 1] Seyum Mangasha, the Commander of the Ethiopian Army of Tigre, to withdraw a day's march away from the Mareb River. Later, he ordered Ras Seyum and Dejazmach[nb 2] Haile Selassie Gugsa, also in the area, to move back fifty-five and thirty-five miles from the border.[2]

Italy declared aggressor

On 7 October, the League of Nations declared Italy the aggressor and started the slow process of imposing sanctions. However, these sanctions did not extend to several vital materials, such as oil. The British and French argued that if they refused to sell oil to the Italians, the Italians would then simply get it from the United States, which was not a member of the League (the British and French wanted to keep Mussolini on side in the event of war with Germany, which by 1935 was looking like a distinct possibility). In an effort to find compromise, the Hoare-Laval Plan was drafted (which essentially handed 3/5ths of Ethiopia to the Italians without Ethiopia's consent on the condition the war ended immediately), but when news of the deal was leaked public outrage was such that the British and French governments were forced to wash their hands of the whole affair.

Surrender of Haile Selassie Gugsa

On 11 October, Dejazmach Haile Selassie Gugsa and 1,200 of his followers surrendered to the commander of the Italian outpost at Adagamos. De Bono notified Rome and the Ministry of Information promptly exaggerated the importance of the surrender for propaganda purposes. Haile Selassie Gugsa was Emperor Haile Selassie's son-in-law. But less than a tenth of Haile Selassie Gugsa's army defected with him. Two weeks before the invasion, Haile Selassie had been warned that Haile Selassie Gugsa was not to be trusted and he was shown evidence that suggested that his son-in-law was already in the pay of the Italians. But the Emperor had shrugged it off.[5][6]

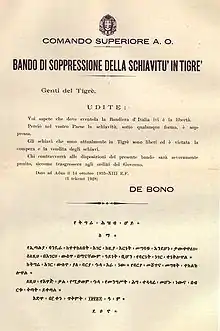

Slavery abolished

On 14 October, De Bono issued a proclamation ordering the suppression of slavery. However, he was to write: "I am obliged to say that the proclamation did not have much effect on the owners of slaves and perhaps still less on the liberated slaves themselves. Many of the latter, the instant they were set free, presented themselves to the Italian authorities, asking 'And now who gives me food?'"[5]

Axum

By 15 October, De Bono's forces moved on from Adwa for a bloodless occupation of the holy capital of Axum. The old Fascist entered the city riding triumphantly on a white horse. However, the invading Italians he commanded looted the Obelisk of Axum and, in 1937, it was taken to Rome.

Ethiopian mobilization on the northern front

Meanwhile, the Ethiopians had mobilized on the northern front. On 17 October, for four hours in Addis Ababa the 70,000 strong Mahel Safari[nb 3] jogged past the Emperor. The Mahel Safari was led by Ras Mulugeta Yeggazu, the Minister of War. Ras Mulugeta and the Mahel Safari then moved out by foot along the "Imperial Highway" to Dessie. From Dessie, Ras Mulugeta moved his army slowly north towards Amba Aradam. The Mahel Safari halted along the way to raze villages and to flog the chiefs of the recalcitrant Azebu and Raya Oromo.[7]

In Gondar, the capital of Begemder Province, Ras Kassa Haile Darge of Shewa Province called a chitet, the traditional mustering of the provincial levies[nb 4] in Begemder. Ras Kassa raised an army of 160,000 men. Ras Kassa's oldest son, Dejazmach Wondosson Kassa, was Shum[nb 5] of Begemder. With one-third of this total number, Ras Kassa, along with sons Aberra Kassa, Asfawossen Kassa, and Wondosson Kassa, moved north to link up with Ras Seyum in the area around Abbi Addi.

In Debra Markos, the capital of Gojjam Province, Ras Imru Haile Selassie raised an army of 25,000. He moved north into the area around Shire. In Semien and Wolkait, Fitawrari[nb 6] Ayalew Birru was already threatening the Eritrean frontier with 10,000 mountaineers.[9]

Mek'ele

De Bono's advance continued methodically, deliberately, and, to the consternation of Mussolini, somewhat slowly. On 8 November, the I Corps and the Eritrean Corps captured Mek'ele, Haile Selassie Gugsa's capital in eastern Tigre. This proved to be the limit of how far the Italian invaders would get under the command of De Bono. Increasing pressure from the rest of the world on Mussolini caused him to need fast glittering victories. He was not prepared to hear of obstacles or delays from De Bono.[10]

Aftermath

On 16 November, De Bono was promoted to the rank of Marshal of Italy (Maresciallo d'Italia). But, in December, he was replaced on the northern front because of the slow, cautious nature of his advance. On 17 December, De Bono received State Telegram 13181 (Telegrama di Stato 13181) which indicated that, with the capture of Makale, his mission was accomplished.[11] He was replaced by Marshal Pietro Badoglio.[12]

Almost immediately, Badoglio was faced with an Ethiopian counterattack known as the Christmas Offensive.

Notes

- Footnotes

- Citations

- Baer, Test Case: Italy, Ethiopia, and the League of Nations, p. 12

- Barker, A. J., The Rape of Ethiopia 1936, p. 33

- Nicolle, The Italian Invasion of Abyssinia 1935–1936, p. 11

- Also spelled Adowa.

- Barker, A. J., The Rape of Ethiopia 1936, p. 35

- Time Magazine, Monday, 18 November 1935, Gugsa Makes Good

- Mockler, pp. 72–73

- Nicholle. The Italian Invasion of Abyssinia 1935–1936, p. 13

- Mockler, p. 73

- Barker, A. J., The Rape of Ethiopia 1936, p. 36

- Marcus, A History of Ethiopia, p. 68

- Nicolle, The Italian Invasion of Abyssinia 1935–1936, p. 8

References

- Baer, George W. (1976). Test Case: Italy, Ethiopia, and the League of Nations. Stanford, California: Hoover Institute Press, Stanford University. ISBN 0-8179-6591-2.

- Barker, A.J. (1971). Rape of Ethiopia, 1936. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-345-02462-6.

- Marcus, Harold G. (1994). A History of Ethiopia. London: University of California Press. pp. 316. ISBN 0-520-22479-5.

- Mockler, Anthony (2002). Haile Sellassie's War. New York: Olive Branch Press. ISBN 978-1-56656-473-1.

- Nicolle, David (1997). The Italian Invasion of Abyssinia 1935–1936. Westminster, MD: Osprey. pp. 48. ISBN 978-1-85532-692-7.

External links

- Time Magazine, Monday, 18 November 1935, Gugsa Makes Good