Battle of Adwa

The Battle of Adwa (Amharic: አድዋ; Tigrinya: ዓድዋ; Italian Adua, also spelled Adowa) was the climactic battle of the First Italo-Ethiopian War. The Ethiopian forces, who had high numerical superiority and weapons supplied by Russia and France, defeated the Italian invading force on Sunday 1 March 1896, near the town of Adwa. The decisive victory thwarted the campaign of the Kingdom of Italy to expand its colonial empire in the Horn of Africa. By the end of the 19th century, European powers had carved up almost all of Africa after the Berlin Conference; only Ethiopia, Liberia and the Dervish State[17] still maintained their independence.[18] Adwa became a pre-eminent symbol of pan-Africanism and secured Ethiopia's sovereignty until the Second Italo-Ethiopian War forty years later.[19]

| Battle of Adwa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Italo-Ethiopian War | |||||||||

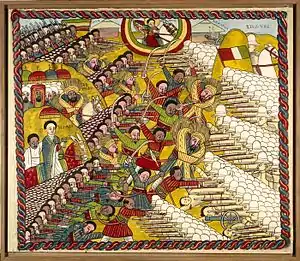

Ethiopian forces, assisted by St George (top), win the battle. Painted 1965–75. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by: | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam Makonnen Wolde Mikael Mikael of Wollo Ras Alula Taytu Betul Ras Mengesha Ras Woldemichael |

Vittorio Dabormida † Giuseppe Arimondi † Matteo Albertone (POW) Giuseppe Ellena | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

80,000 (armed with rifles)[6][nb 1] 20,000 (armed with spears & swords)[6] 8,600 horses[6] 42 artillery pieces 15 Russian advisors[8] Total: 100,000 |

10,443 Italians 4,076 Ascari[9][10] 56 mountain guns[10] (and rifles of an obsolete pattern)[11][8] Total: 14,519 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

3,886 killed[12][nb 2] 6,000 wounded[nb 3] |

3,643 killed[12][nb 4] 1,681 captured[12] 56 mountain guns captured[16] | ||||||||

Location within Ethiopia | |||||||||

Background

In 1889, the Italians signed the Treaty of Wuchale with then Negus[nb 5] Menelik of Shewa. The treaty ceded territories previously part of Ethiopia, namely the provinces of Bogos, Hamasien, Akele Guzai, Serae, and parts of Tigray. In return, Italy promised Menelik II continued rule, financial assistance and military supplies. A dispute later arose over the interpretation of the two versions of the document. The Italian-language version of the disputed Article 17 of the treaty stated that the Emperor of Ethiopia was obliged to conduct all foreign affairs through Italian authorities. This would in effect make Ethiopia a protectorate of the Kingdom of Italy. The Amharic version of the article however, stated that the Emperor could use the good offices of the Kingdom of Italy in his relations with foreign nations if he wished. However, the Italian diplomats claimed that the original Amharic text included the clause and that Menelik II knowingly signed a modified copy of the Treaty.[20]

The Italian government decided on a military solution to force Ethiopia to abide by the Italian version of the treaty. As a result, Italy and Ethiopia came into confrontation, in what was later to be known as the First Italo-Ethiopian War. In December 1894, Bahta Hagos led a rebellion against the Italians in Akele Guzai, in what was then Italian controlled Eritrea. Units of General Oreste Baratieri's army under Major Pietro Toselli crushed the rebellion and killed Bahta. The Italian army then occupied the Tigrayan capital, Adwa. In January 1895, Baratieri's army went on to defeat Ras Mengesha Yohannes in the Battle of Coatit, forcing Mengesha to retreat further south.

By late 1895, Italian forces had advanced deep into Ethiopian territory. On 7 December 1895, Ras Makonnen Wolde Mikael, Ras Welle Betul and Ras Mengesha Yohannes commanding a larger Ethiopian group of Menelik's vanguard annihilated a small Italian unit at the Battle of Amba Alagi. The Italians were then forced to withdraw to more defensible positions in Tigray Province, where the two main armies faced each other. By late February 1896, supplies on both sides were running low. General Oreste Baratieri, commander of the Italian forces, knew the Ethiopian forces had been living off the land, and once the supplies of the local peasants were exhausted, Emperor Menelik II's army would begin to melt away. However, the Italian government insisted that General Baratieri act.

On the evening of 29 February, Baratieri, about to be replaced by a new governor, General Baldissera, met with his brigadier generals Matteo Albertone, Giuseppe Arimondi, Vittorio Dabormida, and Giuseppe Ellena, concerning their next steps. He opened the meeting on a negative note, revealing to his brigadiers that provisions would be exhausted in less than five days, and suggested retreating, perhaps as far back as Asmara. His subordinates argued forcefully for an attack, insisting that to retreat at this point would only worsen the poor morale.[21] Dabormida exclaiming, "Italy would prefer the loss of two or three thousand men to a dishonorable retreat." Baratieri delayed making a decision for a few more hours, claiming that he needed to wait for some last-minute intelligence, but in the end announced that the attack would start the next morning at 9:00am.[22] His troops began their march to their starting positions shortly after midnight.

Forces assembled

The Italian army consisted of four brigades, totaling 17,978 troops with fifty-six artillery pieces.[23] However, it is likely that fewer fought in the actual battle on the Italian side: Harold Marcus notes that "several thousand" soldiers were needed in support roles and to guard the lines of communication to the rear. He accordingly estimates that the Italian force at Adwa consisted of 14,923 effective combat troops.[24] One brigade under General Albertone was made up of Eritrean Ascari led by Italian officers.[25] The remaining three brigades were Italian units under Brigadiers Dabormida, Ellena and Arimondi. While these included elite Bersaglieri and Alpini units, a large proportion of the troops were inexperienced conscripts recently drafted from metropolitan regiments in Italy into newly formed "d'Africa" battalions for service in Africa. Additionally, a limited number of troops were from the Cacciatori d'Africa; units permanently serving in African and in part recruited from Italian settlers.[26][27]

As Chris Prouty describes:

They [the Italians] had inadequate maps, old-model guns, poor communication equipment and inferior footgear for the rocky ground. (The newer Carcano Model 91 rifles were not issued because Baratieri, under constraints to be economical, wanted to use up the old cartridges.) Morale was low as the veterans were homesick and the newcomers were too inexperienced to have any esprit de corps. There was a shortage of mules and saddles.[28]

Order of battle

Ethiopian forces

- Shewa forces; Negus Negasti Menelik II: 25,000 rifles / 3,000 horses / 32 guns[6]

- Semien forces; Itaghiè Taytu: 3,000 rifles / 600 horses / 4 guns[6]

- Gojjam forces; Negus Tekle Haymanot: 5,000 rifles[6]

- Harar forces; Ras Makonnen: 15,000 rifles[6]

- Tigray and Hamasen forces; Ras Mengesha Yohannes and Ras Alula (Abba Nega): 12,000 rifles / 6 guns[6]

- Wollo forces; Ras Mikael: 6,000 rifles / 5,000 horses[6]

- Forces of the Ras Mengesha Atikim: 6,000 rifles[6]

- Forces of Ras Oliè and others: 8,000 rifles[6]

- In addition there were ~20,000 spearmen and swordsmen as well as an unknown number of armed peasants.[6]

Estimates for the Ethiopian forces under Menelik range from a low of 73,000 to a high of over 120,000, outnumbering the Italians by an estimated five or six times.[29] The forces were divided among Emperor Menelik, Empress Taytu Betul, Ras Wale Betul, Ras Mengesha Atikem, Ras Mengesha Yohannes, Ras Alula Engida (Abba Nega), Ras Mikael of Wollo, Ras Makonnen Wolde Mikael, Fitawrari[nb 6] Gebeyyehu, and Negus[nb 7] Tekle Haymanot Tessemma.[30] In addition, the armies were followed by a similar number of camp followers who supplied the army, as had been done for centuries.[31] Most of the army consisted of riflemen, a significant percentage of whom were in Menelik's reserve; however, there were also a significant number of cavalry and infantry only armed with lances (those with lances were referred to as "lancer servants").[31] The Kuban Cossack army officer N. S. Leontiev who visited Ethiopia in 1895,[32][33] according to some sources, led a small team of Russian advisers and volunteers.[34][35][36] Other sources assert that Leontiev did not in fact participate in the battle, rather he visited Ethiopia first unofficially in January 1895, and then officially as a representative of Russia in August 1895, but then left later that year, only to return after the Battle of Adwa.[37]

Wollo Amhara and Oromo Muslim Cavalry

In a recent Amharic publication authored by Andargachew Tsige, an important figure in Ethiopian politics, he references the book "The Battle of Adwa" by Raymond Jonas, and wrote that a 70,000 strong army of Muslim horse men from Wollo (Negus Mikael's cavalry) engaged Italian advancing forces in fierce battles inflicting heavy damage.. However, the Muslim dead soldiers were left unburied although Italians were offered the chance to bury their dead. Muslims follow strict religious rules that require they bury their dead within 24 hrs but it is not clear why they were not given that possibility.

Italian forces

The Italian operational corps in Eritrea was under the command of General Oreste Baratieri. The chief of staff was Lieutenant Colonel Giacchino Valenzano.

- Right column: (3,800 rifles / 18 cannons)[10] 2nd Infantry Brigade (Gen. Vittorio Dabormida);

- 3rd Africa Infantry Regiment,[38] (Col. Ragni)

- 5th Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. Giordano)

- 6th Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. Prato)

- 10th Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. De Fonseca)

- 6th Africa Infantry Regiment (Col. Airaghi)

- 3rd Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. Branchi)

- 13th Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. Rayneri)

- 14th Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. Solaro)

- Native Mobile Militia Battalion (Maj. De Vito)

- Native Company from the Asmara Chitet[39] (Cpt. Sermasi)

- 2nd Artillery Brigade (Maj. Zola)

- 3rd Africa Infantry Regiment,[38] (Col. Ragni)

- Central column: (2,493 rifles / 12 cannons)[10] 1st Infantry Brigade (Gen. Giuseppe Arimondi);

- 1st Africa Bersaglieri Regiment[41] (Col. Stevani)

- 1st Africa Bersaglieri Battalion (Maj. De Stefano)

- 2nd Africa Bersaglieri Battalion (Maj. Compiano)

- 1st Africa Infantry Regiment (Col. Brusati)

- 2nd Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. Viancini)

- 4th Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. De Amicis)

- 9th Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. Baudoin)

- 1st Company of the 5th Native Battalion (Cpt. Pavesi)

- 8th Mountain Artillery Battery[40] (Cpt. Loffredo)

- 11th Mountain Artillery Battery[40] (Cpt. Franzini)

- 1st Africa Bersaglieri Regiment[41] (Col. Stevani)

- Left column: (4,076 rifles / 14 cannons)[10] Native Brigade (Gen. Matteo Albertone);

- 1st Native Battalion (Maj. Turitto)

- 6th Native Battalion (Maj. Cossu)

- 5th Native Battalion (Maj. Valli)

- 8th Native Battalion (Maj. Gamerra)

- "Okulè Kusai" Native Irregular Company (Lt. Sapelli)

- 1st Artillery Brigade (Maj. De Rosa)

- Reserve column: (4,150 rifles /12 cannons)[10] 3rd Infantry Brigade (Gen. Giuseppe Ellena);

- 4th Africa Infantry Regiment (Col. Romero)

- 7th Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. Montecchi)

- 8th Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. Violante)

- 11th Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. Manfredi)

- 5th Africa Infantry Regiment (Col. Nava)

- 15th Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. Ferraro)

- 16th Africa Infantry Battalion (Maj. Vandiol)

- 1st Africa Alpini Battalion (Lt. Col. Menini)

- 3rd Native Battalion (Lt. Col. Galliano)

- 1st Quick Fire Artillery Battery (Cpt. Aragno)

- 2nd Quick Fire Artillery Battery (Cpt. Mangia)

- Sappers company

- 4th Africa Infantry Regiment (Col. Romero)

Budget restrictions and supply shortages meant that many of the rifles and artillery pieces issued to the Italian reinforcements sent to Africa were obsolete models, while clothing and other equipment was often substandard. The logistics and training of the recently arrived conscript contingents from Italy were inferior to the experienced colonial troops based in Eritrea.[44]

Battle

On the night of 29 February and the early morning of 1 March, three Italian brigades advanced separately towards Adwa over narrow mountain tracks, while a fourth remained camped.[45] David Levering Lewis states that the Italian battle plan:

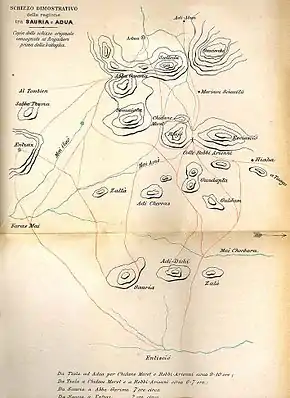

called for three columns to march in parallel formation to the crests of three mountains – Dabormida commanding on the right, Albertone on the left, and Arimondi in the center – with a reserve under Ellena following behind Arimondi. The supporting crossfire each column could give the others made the 'soldiers as deadly as razored shears'. Albertone's brigade was to set the pace for the others. He was to position himself on the summit known as Kidane Mehret, which would give the Italians the high ground from which to meet the Ethiopians.[46]

However, the three leading Italian brigades had become separated during their overnight march and by dawn were spread across several miles of very difficult terrain. Their sketchy maps caused Albertone to mistake one mountain for Kidane Meret, and when a scout pointed out his mistake, Albertone advanced directly into Ras Alula's position.

Unbeknownst to General Baratieri, Emperor Menelik knew his troops had exhausted the ability of the local peasants to support them and had planned to break camp the next day (2 March). The Emperor had risen early to begin prayers for divine guidance when spies from Ras Alula (Abba Nega), his chief military advisor, brought him news that the Italians were advancing. The Emperor summoned the separate armies of his nobles and with the Empress Taytu beside him, ordered his forces forward. Negus Tekle Haymanot commanded the right wing with his troops from Gojjam, Ras Alula the left with his troops from Tigray, Ras Makonnen and Ras Mengesha Yohannes the center, and Ras Mikael at the north side leading the Wollo Amhara cavalry;[47] the Emperor and his consort remained with the reserve.[46] The Ethiopian forces positioned themselves on the hills overlooking the Adwa valley, in perfect position to receive the Italians, who were exposed and vulnerable to crossfire.[31]

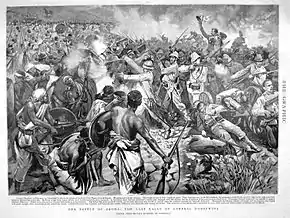

Albertone's Ascari Brigade was the first to encounter the onrush of Ethiopians at 06:00, near Kidane Meret,[48] where the Ethiopians had managed to set up their mountain artillery. Accounts of the Ethiopian artillery deployed at Adwa differ; Russian advisor Leonid Artamonov wrote that it comprised forty-two Russian mountain guns supported by a team of fifteen advisers,[34] but British writers suggest that the Ethiopian guns were Hotchkiss and Maxim pieces captured from the Egyptians or purchased from French and other European suppliers.[49] Albertone's heavily outnumbered Ascaris held their position for two hours until Albertone's capture, and under Ethiopian pressure the survivors sought refuge with Arimondi's brigade. Arimondi's brigade beat back the Ethiopians who repeatedly charged the Italian position for three hours with gradually fading strength until Menelik released his reserve of 25,000 Shewans and swamped the Italian defenders. Two companies of Bersaglieri who arrived at the same moment could not help and were cut down.[9]

Dabormida's Italian Brigade had moved to support Albertone but was unable to reach him in time. Cut off from the remainder of the Italian Army, Dabormida began a fighting retreat towards friendly positions. However, he inadvertently marched his command into a narrow valley where the Wollo Amhara cavalry under Ras Mikael slaughtered his brigade, while shouting Ebalgume! Ebalgume! ("Reap! Reap!"). Dabormida's remains were never found, although his brother learned from an old woman living in the area that she had given water to a mortally wounded Italian officer, "a chief, a great man with spectacles and a watch, and golden stars".[50]

The remaining two brigades under Baratieri himself were outflanked and destroyed piecemeal on the slopes of Mount Belah. Menelik watched as Gojjam forces under the command of Tekle Haymonot made quick work of the last intact Italian brigade. By noon, the survivors of the Italian army were in full retreat and the main battle was over. The Ethiopian pursuit continued for nine miles until the late afternoon, while local peasants alerted by signal fires killed Italian and Ascari stragglers throughout the night.[51]

Immediate aftermath

The Italians suffered about 6,000 killed and 1,500 wounded in the battle and subsequent retreat back into Eritrea, with 3,000 taken prisoner. Brigadiers Dabormida and Arimondi were amongst the dead. Ethiopian losses have been estimated at around 4,000–5,000 killed and 8,000 wounded.[45][16] In their flight to Eritrea, the Italians left behind all of their artillery and 11,000 rifles, as well as most of their transport.[16] As Paul B. Henze notes, "Baratieri's army had been completely annihilated while Menelik's was intact as a fighting force and gained thousands of rifles and a great deal of equipment from the fleeing Italians."[52] The 3,000 Italian prisoners, who included Brigadier Albertone, appear to have been treated as well as could be expected under difficult circumstances, though about 200 died of their wounds in captivity.[53]

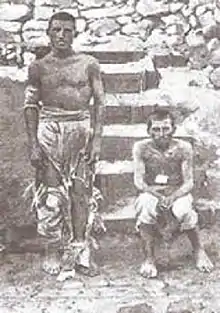

However, 800 captured Eritrean Ascari, regarded as traitors by the Ethiopians, had their right hands and left feet amputated.[54][55] Augustus Wylde records when he visited the battlefield months after the battle, the pile of severed hands and feet was still visible, "a rotting heap of ghastly remnants."[56] Further, many Ascari had not survived their punishment, Wylde writing how the neighborhood of Adwa "was full of their freshly dead bodies; they had generally crawled to the banks of the streams to quench their thirst, where many of them lingered unattended and exposed to the elements until death put an end to their sufferings."[57] There does not appear to be any foundation for reports that some Italians were castrated and these may reflect confusion with the atrocious treatment of the Ascari prisoners.[58]

Baratieri was relieved of his command and later charged with preparing an "inexcusable" plan of attack and for abandoning his troops in the field. He was acquitted on these charges but was described by the court martial judges as being "entirely unfit" for his command.

Public opinion in Italy was outraged.[59] Chris Prouty offers a panoramic overview of the response in Italy to the news:

When news of the calamity reached Italy there were street demonstrations in most major cities. In Rome, to prevent these violent protests, the universities and theatres were closed. Police were called out to disperse rock-throwers in front of Prime Minister Crispi's residence. Crispi resigned on 9 March. Troops were called out to quell demonstrations in Naples. In Pavia, crowds built barricades on the railroad tracks to prevent a troop train from leaving the station. The Association of Women of Rome, Turin, Milan and Pavia called for the return of all military forces in Africa. Funeral masses were intoned for the known and unknown dead. Families began sending to the newspapers letters they had received before Adwa in which their menfolk described their poor living conditions and their fears at the size of the army they were going to face. King Umberto declared his birthday (14 March) a day of mourning. Italian communities in St. Petersburg, London, New York, Chicago, Buenos Aires and Jerusalem collected money for the families of the dead and for the Italian Red Cross.[60]

The Russian support for Ethiopia led to the advent of a Russian Red Cross mission. The Russian mission was a military mission conceived as a medical support for the Ethiopian troops. It arrived in Addis Ababa some three months after Menelik's Adwa victory.[61] In 1895 Emperor Menelik II invited Leontiev to return to Ethiopia with a Russian military mission. Leontiev organized a delivery of Russian weapons for Ethiopia: 30,000 rifles, 5,000,000 cartridges, 5000 sabres, and a few cannons.[62][63]

Follow-up to Ethiopian victory

Emperor Menelik decided not to follow up on his victory by attempting to drive the routed Italians out of their colony. The victorious Emperor limited his demands to little more than the abrogation of the Treaty of Wuchale. In the context of the prevailing balance of power, the emperor's crucial goal was to preserve Ethiopian independence. In addition, Ethiopia had just begun to emerge from a long and brutal famine; Harold Marcus reminds us that the army was restive over its long service in the field, short of rations, and the short rains which would bring all travel to a crawl would soon start to fall.[64] At the time, Menelik claimed a shortage of cavalry horses with which to harry the fleeing soldiers. Chris Prouty observes that "a failure of nerve on the part of Menelik has been alleged by both Italian and Ethiopian sources."[65] Lewis believes that it "was his farsighted certainty that total annihilation of Baratieri and a sweep into Eritrea would force the Italian people to turn a bungled colonial war into a national crusade"[66] that stayed his hand.

As a direct result of the battle, Italy signed the Treaty of Addis Ababa, recognizing Ethiopia as an independent state. Almost forty years later, on 3 October 1935, after the League of Nations's weak response to the Abyssinia Crisis, the Italians launched a new military campaign endorsed by Benito Mussolini, the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. This time the Italians employed vastly superior military technology such as tanks and aircraft, as well as chemical warfare, and the Ethiopian forces were defeated by May 1936. Following the war, Italy occupied Ethiopia for five years (1936–41), before eventually being driven out during World War II by British Empire and Ethiopian Arbegnoch (patriot)[67] forces.

Significance

"The confrontation between Italy and Ethiopia at Adwa was a fundamental turning point in Ethiopian history," writes Henze.[68] On a similar note, the Ethiopian historian Bahru Zewde observed that "few events in the modern period have brought Ethiopia to the attention of the world as has the victory at Adwa".[69]

The Russian Empire had sold many artillery pieces to the Ethiopian forces and paid enthusiastic compliments to the Ethiopian success. One of the documents of that time stated "The Victory immediately gained the general sympathy of Russian society and it continued to grow." The unique outlook which polyethnic Russia exhibited to Ethiopia disturbed many supporters of European nationalism during the twentieth century.[32][33] The Russian Cossack captain Nikolay Leontiev with a small escort was present at the battle as an observer.[35][70]

This defeat of a colonial power and the ensuing recognition of African sovereignty became rallying points for later African nationalists during their struggle for decolonization, as well as activists and leaders of the Pan-African movement.[19] As the Afrocentric scholar Molefe Asante explains,

After the victory over Italy in 1896, Ethiopia acquired a special importance in the eyes of Africans and black people all over the world alike ,as the only surviving African State that successfully defeated a European colonial power in open battle. Italy's government who had viewed them as an inferior barbaric race were brought to their knees and subsequently forced to recognize the African nation of Ethiopia as an equal. After Adowa, Ethiopia became emblematic of African valor and resistance, the bastion of prestige and hope to thousands of Africans who were experiencing the full shock of European conquest and were beginning to search for an answer to the myth of African and black inferiority as well as invoking a strong sense of Pan-Africanism towards to people of African-american origins who had suffered equally appalling injustices at the time and many centuries before. [71]

On the other hand, many writers have pointed out how this battle was a humiliation for the Italian military. Italian historian Tripodi pinpointed that some of the roots of the rise of Fascism in Italy went back to this defeat and to the need to "avenge" the defeat that started to be present in the military and nationalistic groups of the Kingdom of Italy. The same Mussolini declared when Italian troops occupied Addis Ababa in May 1936: Adua e' vendicata (Adwa has been avenged).

Indeed, one student of Ethiopia's History, Donald N. Levine, points out that for the Italians Adwa "became a national trauma which demagogic leaders strove to avenge. It also played no little part in motivating Italy's revanchist adventure in 1935". Levine also noted that the victory "gave encouragement to isolationist and conservative strains that were deeply rooted in Ethiopian culture, strengthening the hand of those who would strive to keep Ethiopia from adopting techniques imported from the modern West – resistances with which both Menelik and Ras Teferi/Haile Selassie would have to contend".[18]

Contemporary celebrations of Adwa

Public holiday

The Victory of Adwa is a public holiday in all regional states and charter cities across Ethiopia. All schools, banks, post offices and government offices are closed, with the exceptions of health facilities. Some taxi services and public transports choose not to operate on this day. Shops are normally open but most close earlier than usual.[72]

Public celebrations

The Victory of Adwa, being a public holiday, is commemorated in public spaces. In Addis Ababa, the Victory of Adwa is celebrated at Menelik Square with the presence of government officials, patriots, foreign diplomats and the general public. The Ethiopian Police Orchestra play various patriotic songs as they walk around Menelik Square.[73]

The public dress up in traditional Ethiopian patriotic attire. Men often wear Jodhpurs and various types of vest; they carry the Ethiopian flag and various patriotic banners and placards, as well as traditional Ethiopian shields and swords called Shotel. Women dress up in different patterns of handcrafted traditional Ethiopian clothing, known in Amharic as Habesha kemis. Some wear black gowns over all, while others put royal crowns on their heads. Women's styles of dress, like their male counterparts, imitate the traditional styles of Ethiopian patriotic women. Of particular note is the dominant presence of the Empress Taytu Betul during these celebrations.[72][73]

The Empress Taytu Betul is the beloved and influential wife of Emperor Menelik II, who played a significant role during the Battle of Adwa. Although often overlooked, thousands of women participated in the Battle of Adwa alongside men. Some were trained as nurses to attend to the wounded, while others mainly cooked and supplied food and water to the soldiers and comforted the wounded.[73]

In addition to Addis Ababa, other major cities in Ethiopia, including Bahir Dar, Debre Markos and the town of Adwa itself, where the battle took place, celebrate the Victory of Adwa in public ceremonies.[72]

Symbols

Several images and symbols are used during the commemoration of the Victory of Adwa, including the tri-coloured Green, Gold and Red Ethiopian flag, images of Emperor Menelik II and Empress Taytu Betul, as well as other prominent kings and war generals of the time including King Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam, King Michael of Wollo, Dejazmach Balcha Safo, Fitawrari Habte Giyorgis Dinagde, and Fitawrari Gebeyehu, among others. Surviving members of the Ethiopian patriotic battalions wear the various medals that they collected for their participation during different battle fields. Young people often wear T-shirts adorned by Emperor Menelik II, Empress Taytu, Emperor Haile Selassie and other notable members of the Ethiopian monarchy. Popular and patriotic songs are often played on amplifiers. Of particular note are Ejigayehu Shibabaw’s ballad dedicated to the Battle of Adwa and Teddy Afro’s popular song "Tikur Sew", which literally translates to "black man or black person" – a poetic reference to Emperor Menelik II’s decisive African victory over Europeans, as well as the Emperor's darker skin complexion.

Film

- Adwa – 1999 documentary film directed by Haile Gerima

Notes

Footnotes

- According to Pankhurst, the Ethiopians were armed with approximately 100,000 rifles of which about half were "fast firing.".[7]

- Not including the notables like Däjjazmach Bäshah Aboyé †, Fitawrari Dämtew Kätäma †, Fitawrari Täkle of Wälläga †, Fitawrari Gebeyehu † or Qäññazmach Taffäsä Abaynäh † and several others who, by the chronicler Yoséf Negusé, were listed separately with name[13]

- Leontiev's diary recorded that the various commanders had reported to Menilek losses of some 4,000 dead and 6,000 wounded[14]

- Corpses retrieved by the burial commission in April 1896. Officially 3,025 Italians and 618 Ascari[15]

- Roughly equivalent to King.

- Roughly equivalent to Commander of the Vanguard.

- Roughly equivalent to King.

Citations

- Spencer, John H. (2006). Ethiopia at Bay. Tsehai Puiblishers. p. 31.

- The activities of the officer the Kuban Cossack army N. S. Leontjev in the Italian-Ethiopic war in 1895–1896 Archived 28 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- Richard, Pankhurst. "Ethiopia's Historic Quest for Medicine, 6". The Pankhurst History Library. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011.

- Soviet Appeasement, Collective Security, and the Italo-Ethiopian war of 1935 and 1936

- Thomas Wilson, Edward (1974). Russia and Black Africa Before World War II. New York. p. 57-58.

- McLachlan, Sean (2011). Armies of the Adowa Campaign 1896. Osprey Publishing. p. 42.

- Pankhurst, The Ethiopians, p. 190

- Mekonnen, Yohannes (2013). Ethiopia: the Land, Its People, History and Culture. New Africa Press. pp. 76–80.

- Mclachlan, Sean. Armies of the Adowa Campaign 1896. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-84908-457-4.

- Abdussamad H. Ahmad and Richard Pankhurst (1998). Adwa Victory Centenary Conference, 26 February – 2 March 1996. Addis Ababa University. pp. 158–62.

- Mclachlan, Sean. Armies of the Adowa Campaign 1896. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-84908-457-4.

- Caulk, Richard (2002). "Between the Jaws of Hyenas": A Diplomatic History of Ethiopia (1876-1896). Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden. pp. 563, 566–567.

- Richard Caulk, "Between the Jaws of Hyenas": A Diplomatic History of Ethiopia (1876-1896), p. 567

- Richard Caulk, "Between the Jaws of Hyenas": A Diplomatic History of Ethiopia (1876-1896), p. 566

- Richard Caulk, "Between the Jaws of Hyenas": A Diplomatic History of Ethiopia (1876-1896), p. 563

- Pankhurst. The Ethiopians, pp. 191–92.

- Jihad in the Arabian Sea 2011, Camille Pecastaing, In the land of the Mad Mullah: Somalia

- "The Battle of Adwa as a 'Historic' Event", Ethiopian Review, 3 March 2009 (Retrieved 9 March 2009)

- Professor Kinfe Abraham, "The Impact of the Adowa Victory on The Pan-African and Pan-Black Anti-Colonial Struggle," Address delivered to The Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University, 8 February 2006

- Piero Pastoretto. "Battaglia di Adua" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 31 May 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- Harold G. Marcus, The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia 1844–1913, 1975 (Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press, 1995), p. 170

- David Levering Lewis, The Race for Fashoda (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987), p. 116. ISBN 1-55584-058-2

- Lewis, Fashoda, pp. 116f. He breaks down their numbers into 10,596 Italian officers and soldiers and 7,104 Eritrean askaris.

- Marcus, Menelik II, p. 173

- Thomas Pakenham, p. 481 The Scramble for Africa, ISBN 0-349-10449-2

- George Fitz-Hardinge Berkley The Campaign of Adowa and the rise of Menelik, London: Constable 1901.

- Raffaele Ruggeri, p. 82 Le Guerre Coloniali Italiane 1885/1900, Editrice Militare Italiana 1988

- Prouty, Chris (1986). Empress Taytu and Menilek II. Trenton: The Red Sea Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-932415-11-3.

- Pankhurst has published one collection of these estimates, Economic History of Ethiopia (Addis Ababa: Haile Selassie University, 1968), pp. 555–57. See also Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A–C. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2003, p. 108.

- Pétridès (as well as Pankhurst, with slight variations) break the troop numbers down (over 100,000 by their estimates) as follows: 35,000 infantry (25,000 riflemen and 10,000 spearmen) and 8,000 cavalry under Emperor Menelik; 5,000 infantry under Empress Taytu; 8,000 infantry (6,000 riflemen and 2,000 spearmen) under Ras Wale; 8,000 infantry (5,000 riflemen and 3,000 spearmen) under Ras Mengesha Atikem, 5,000 riflemen, 5,000 spearmen, and 3,000 cavalry under Ras Mengesha Yohannes and Ras Alula Engida; 6,000 riflemen, 5,000 spearmen, and 5,000 Amhara cavalry under Ras Mikael of Wollo; 25,000 Amhara riflemen under Ras Makonnen; 8,000 Amhara infantry under Fitawrari Gebeyyehu Gora; 5,000 riflemen, 5,000 spearmen, and 3,000 cavalry under Negus Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam, von Uhlig, Encyclopedia, p. 109.

- Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A–C (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2003), p. 108.

- Russian Mission to Abyssina.

- Who Was Count Abai? Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- "ДОКУМЕНТЫ->ЭФИОПИЯ->Л. К. АРТАМОНОВ->ЧЕРЕЗ ЭФИОПИЮ К БЕРЕГАМ БЕЛОГО НИЛА->ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ". www.vostlit.info. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "Виноградова К.В. - Научная Конференция, Симпозиум, Конгресс на Проекте SWorld - Апробация, Сборник научных трудов и Монография - Россия, Украина, Казахстан, СНГ - 1. Всемирная история и история Украины". www.sworld.com.ua. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "– With the Armies of Menelik II by Alexander K. Bulatovich". Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Raymond Jonas, "The Battle of Adwa" (Harvard University Press, 2011), pp. 310–14.

- Italian national units, formed for service in the colonies with personnel drawn from the regular infantry regiments of the Army.

- Native feudal levy.

- Six light 75mm bronze rifled breach-loading mountain howitzers Mod.75B

- Italian national units, formed for service in the colonies with personnel drawn from the regular Bersaglieri regiments of the Army.

- Six light 75mm bronze rifled breach-loading mountain howitzers Mod.75B.

- Two light 75mm bronze rifled breach-loading mountain howitzers Mod.75B

- Mclachlan, Sean. Armies of the Adowa Campaign 1896. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-1-84908-457-4.

- Uhlig, Encyclopedia, p. 109.

- Lewis, Fashoda, p. 117.

- "Sean McLachlan,page 15 "Armies of the Adowa Campaign 1896: The Italian Disaster in Ethiopia"" (PDF).

- In the attached map, this is labelled "Chidane Meret", which is immediately above (west) of the hill "Rajò".

- Sean McLachlan, p. 37 "Armies of the Adowa Campaign 1896", ISBN 978-1-84908-457-4

- George Fitz-Hardinge Berkeley, Campaign of Adowa (1902), quoted in Lewis, Fashoda, p. 118.

- Mclachlan, Sean. Armies of the Adowa Campaign 1896. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84908-457-4.

- Henze, Layers of Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia (New York: Palgrave, 2000), p. 170.

- Chris Prouty notes that Albertone was given into the care of Azaj Zamanel, commander of Empress Taytu's personal army, and "had a tent to himself, a horse and servants". Empress Taytu, pp. 169ff.

- "Photo of some of the Eritrean Ascari mutilated". Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- McLachlan, Sean. Armies of the Adowa Campaign 1896. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-84908-457-4.

- Augustus B. Wylde, Modern Abyssinia (London: Methuen, 1901), p. 213

- Wylde, Modern Abyssinia, p. 214

- Prouty has collected the few documented experiences of these Italian POWs, none of whom claim to have been treated inhumanely (Empress Taytu, pp. 170–83). She repeats the opinion of the Italian historian Angelo del Boca, that "the paucity of the record is attributable to the glacial welcome received in Italy by the returning prisoners for having lost a war, and the fact that they were subjected to long interrogations when they debarked, were defrauded of their back pay, had their mementoes confiscated and were ordered not to talk to journalists" (p. 170).

- Giuseppe Maria Finaldi, Italian National Identity in the Scramble for Africa: Italy's African Wars in the Era of Nation-Building, 1870–1900 (2010)

- Prouty, Empress Taytu, pp. 159f.

- The Russian Red Cross Mission Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Проза.ру". www.proza.ru. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- Nikolay Stepanovich Leontiev

- Marcus, Menelik II, p. 176.

- Prouty, Empress T'aytu, p. 161.

- Lewis, Fashoda, p. 120.

- Roberts, A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa Vol 7. p. 740. ISBN 0-521-22505-1.

- Henze, Layers of Layers of Time, p.180.

- Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia (London: James Currey, 1991), p. 81.

- "Cossacks of the emperor Menelik II". Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- Molefe Asante, quoted in Rodney Worrell, Pan-africanism in Barbados, (New Academia Publishing: 2005) p. 16

- "Ethiopia Celebrates Victory of Adowa". Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "Adwa victory 122 anniversary colorfully celebrated in Addis Ababa". Retrieved 3 March 2019.

References

- Berkeley, G.F.-H. (1902) The Campaign of Adowa and the Rise of Menelik, Westminister: A. Constable, 403 pp., OCLC 11834888

- Brown, P.S. and Yirgu, F. (1996) The Battle of Adwa 1896, Chicago: Nyala Publishing, 160 pp., ISBN 978-0-9642068-1-6

- Bulatovich, A.K. (nd) With the Armies of Menelik II: Journal of an Expedition from Ethiopia to Lake Rudolf, translated by Richard Seltzer, OCLC 454102384

- Bulatovich, A.K. (2000) Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896–1898, translated by Richard Seltzer, Lawrenceville, N.J. : Red Sea Press, ISBN 978-1-5690211-7-0

- Henze, P.B. (2004) Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia, London: Hurst & Co., ISBN 1-85065-522-7

- Jonas, R.A. (2011) The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire, Bellknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-6740-5274-1

- Lewis, D.L. (1988) The Race to Fashoda: European Colonialism and African Resistance in the Scramble for Africa, 1st ed., London: Bloomsbury, ISBN 0-7475-0113-0

- Marcus, H.G. (1995) The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia, 1844–1913, Lawrenceville, N.J.: Red Sea Press, ISBN 1-56902-010-8

- Pankhurst, K.P. (1968) Economic History of Ethiopia, 1800–1935, Addis Ababa: Haile Sellassie I University Press, 772 pp., OCLC 65618

- Pankhurst, K.P. (1998) The Ethiopians: A History, The Peoples of Africa Series, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, ISBN 0-631-22493-9

- Rosenfeld, C.P. (1986) Empress Taytu and Menelik II: Ethiopia 1883–1910, London: Ravens Educational & Development Services, ISBN 0-947895-01-9

- Uhlig, S. (ed.) (2003) Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, 1 (A–C), Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, ISBN 3-447-04746-1

- Worrell, R. (2005) Pan-Africanism in Barbados: An Analysis of the Activities of the Major 20th-Century Pan-African Formations in Barbados, Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, ISBN 0-9744934-6-5

- Zewde, Bahru (1991) A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855–1974, Eastern African Studies series, London: Currey, ISBN 0-85255-066-9

- With the Armies of Menelik II, emperor of Ethiopia at www.samizdat.com

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Adua. |

- Historynet: Ethiopia's Decisive Victory at Adowa

- Who Was Count Abai?

- The Colony of Eritrea from its Origins until March 1, 1899 from 1899 which details the Battle of Adwa from the World Digital Library

- Painting depicting the Battle of Adwa, Catalogue No. E261845, Department of Anthropology, NMNH, Smithsonian Institution