Decline of Detroit

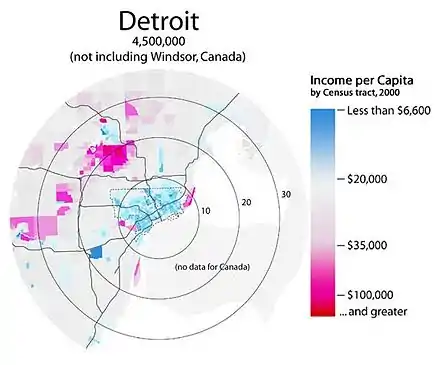

The city of Detroit, in the U.S. state of Michigan, has gone through a major economic and demographic decline in recent decades. The population of the city has fallen from a high of 1,850,000 in 1950 to 680,000 in 2015, removing it off the top 20 of US cities by population for the first time since 1850.[1] However, the city's combined statistical area has a population of 5,318,744 people, which currently ranks 12th in the United States. Local crime rates are among the highest in the United States (despite this, the overall crime rate in the city has seen a decline during the 21st century[2]), and vast areas of the city are in a state of severe urban decay. In 2013, Detroit filed the largest municipal bankruptcy case in U.S. history, which it successfully exited on December 10, 2014. Poverty, crime, shootings, drugs and urban blight in Detroit are ongoing problems.

As of 2017 median household income is rising,[3] criminal activity is decreasing by 5% annually as of 2017,[4] and the city's blight removal project is making progress in ridding the city of all abandoned homes that cannot be rehabilitated.

Contributors to decline

The deindustrialization of Detroit has been a major factor in the population decline of the city.[5]

Role of the automobile industry

Before the advent of the automobile, Detroit was a small, compact regional manufacturing center. In 1900, Detroit had a population of 285,000 people, making it the thirteenth-largest city in the U.S.[6] Over the following decades, the growth of the automobile industry, including affiliated activities such as parts and tooling manufacturing, came to dwarf all other manufacturing in the city. The industry drew a million new residents to the city. At Ford Motor's iconic and enormous River Rouge plant alone, opened in 1927 in Detroit's neighbor Dearborn, there were over 90,000 workers.[6] The shifting nature of the workforce stimulated by the rapid growth of the auto industry had an important impact on the city's future development. The new workers came from diverse and soon far-flung sources. Nearby Canada was important early on and many other workers came from eastern and southern Europe, a large portion of them being ethnic Italians, Hungarians, and Poles. An important attraction for these workers was that the new assembly line techniques required little prior training or education to get a job in the industry.[7]

The breadth of sources for the growing demand for auto assembly mans, however, was sharply limited by the turmoil of World War I, and shortly thereafter by the restrictive U.S. Immigration Act of 1924, with its limited annual quotas for new immigrants. In response, the industry—with Ford in the forefront—turned in a significant way to hiring African-Americans, who were leaving the South in huge numbers in response to the combination of a post-war agricultural slump and continuing Jim Crow practices.[7] At the same time large numbers of southern whites were hired, as well as large numbers of Mexicans, since immigration from most of the western hemisphere was not restricted at all by new immigration quotas. By 1930 Detroit's population had grown to nearly 1.6 million, and then to nearly 2 million by its peak shortly before 1950. A World War II boom in the manufacture of war materiel contributed to this growth surge.[8] This population was, however, very spread out in comparison with other U.S. industrial cities. A variety of factors associated with the auto industry fed this trend. There was the large influx of workers. They earned comparatively high wages in the auto industry. The plants they worked at, belonging to various major and minor manufacturers, were spread around the city. The workers tended to live along extended bus and streetcar lines leading to their workplaces. The result of these influences, beginning already by the 1920s, was that many workers bought or built their own single-family or duplex homes. They did not tend to live in large apartment houses, as in New York, or in closely spaced row houses as in Philadelphia.[8] After New Deal labor legislation, high auto-union secured wages and benefits facilitated this willingness to take on the cost and risk of home ownership, while also reducing the ability of Detroit car manufacturers to compete in the future.[8]

These decentralizing trends did not have equal effects on African-American residents of the city. They tended to have far less access to New Deal mortgage support programs such as Federal Housing Authority and Veterans Administration insured mortgages. African-American neighborhoods were viewed by lenders and the federal programs as riskier, resulting—in this period—in much lower rates of homeownership for African-Americans than other residents of the city.[8]

The auto industry also gave rise to a large number of high paying management and executive jobs. There were also large numbers of attorneys, advertisers, and other workers who supported the industry's managerial force. These workers already by the 1920s had begun to move to neighborhoods well removed from the industry's factories and higher crime rates. This upper stratum moved to outlying neighborhoods, and further, to well-to-do suburbs such as Bloomfield Hills and Grosse Pointe. Oakland County, north of the city, became a popular place to live for executives in the industry. "By the second half of the twentieth century, it was one of the wealthiest counties in the United States, a place profoundly shaped by the concentration of auto-industry-derived wealth."[9]

Public policy was automobile oriented. Funds were directed to the building of expressways for automobile traffic, to the detriment of public transit and the inner-city neighborhoods through which the expressways were cut to get to the auto factories and the downtown office buildings.[10]

These processes, in which the growth of the auto industry had played such a large part, combined with racial segregation to give Detroit, by 1960, its particularly noteworthy character of a substantially African-American inner city surrounded by mainly white outer sections of the city and suburbs. By 1960 there were more whites living in the city's suburbs than the city itself. On the other hand, there were very few African-Americans in the suburbs. Real estate agents would not sell to them, and if African-Americans did try to move into suburbs there was "intense hostility and often violence" in reaction.[10]

The auto industry too was decentralizing away from Detroit proper. This change was facilitated by the great concentration of automobile production into the hands of the "Big Three" of General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler. The Big Three were able to build cars better and cheaper and put nearly every smaller competitor automaker out of business. While this corporate concentration was taking place, the Big Three were shifting their production out of central Detroit to escape the auto-union wage requirements. Between 1945 and 1957 the Big Three built 25 new manufacturing plants in the metropolitan area, not one of them in the city itself.[11]

The number and character of these new, suburban auto factories was a harbinger of future trends detrimental to the economic health of Detroit. There was an interaction between factory decentralization and the nature of the industry's post-New Deal unionized labor force. Ford Motor was one of the first to undertake major decentralization, in reaction to labor developments. Ford's workers voted to join the UAW in 1941. This led Ford to be concerned about the vulnerability of its huge flagship Rouge River plant to labor unrest. The workers at this plant were "among the industry's most well-organized, racially and ethnically diverse, and militant." A strike at this key plant could bring the company's manufacturing operations as a whole to a halt. Ford therefore decentralized operations from this plant, to soften union power (and to introduce new technologies in new plants, and expand to new markets). Ford often built up parallel production facilities, making the same products, so that the effect of a strike at any one facility would be lessened. The results for the River Rouge plant are striking. From its peak labor force of 90,000 around 1930, the number of workers there declined to 30,000 by 1960 and only about 6,000 by 1990. This decline was mainly due to labor movement to non-union areas and automation.[11]

The spread of the auto industry outward from Detroit proper in the 1950s was the beginning of a process that extended much further afield. Auto plants and the parts suppliers associated with the industry were relocated to the southern U.S., and to Canada and Mexico in order to avoid paying higher US-based salaries. The major auto plants left in Detroit were closed down, and their workers increasingly left behind. When the auto industry's facilities moved out, there were dramatically adverse economic ripple effects on the city. The neighborhood businesses that had catered to auto workers shut down. This direct and indirect economic contraction caused the city to lose property taxes, wage taxes, and population (and thus consumer demand). The closed auto plants were also often abandoned in a period before strong environmental regulation, causing the sites to become so-called "brownfields," unattractive to potential replacement businesses because of the pollution hangover from decades of industrial production.[12] The pattern of the deteriorating city by the mid-1960s was visibly associated with the largely departed auto industry. The neighborhoods with the most closed stores, vacant houses, and abandoned lots were in what had formerly been the most heavily populated parts of the city, adjacent to the now-closed older major auto plants.[12]

By the 1970s and 1980s, the auto industry suffered setbacks that further impacted Detroit. The industry encountered the rise of OPEC and the resulting sharp increase in gasoline prices. It faced new and intense international competition, particularly from Italian, Japanese and German automobile manufacturers. Chrysler avoided bankruptcy in the late 1970s only with the aid of a federal bailout. GM and Ford also struggled financially. The industry fought to regain its competitive footing but did so in very substantial part by introducing cost-cutting techniques focused on automation and thus reduction of labor cost and the number of workers. It also relocated ever more of its manufacturing to lower-cost states in the U.S. and to low-income countries. Detroit's residents thus had access to fewer and fewer well-paying, secure auto manufacturing jobs.[12]

The leadership of Detroit failed to diversify the city's industry beyond automotive manufacturers and related industries. Because the city had flourished in the heyday of the auto industry, local politicians made periodic attempts to stimulate a revival of the auto industry in the city. For example, in the 1980s the cities of Detroit and Hamtramck used the power of eminent domain to level part of what had been Poletown to make a parking lot for a new automobile factory. On that site, a new, low-rise suburban type Cadillac plant was built, with substantial government subsidies. The new Detroit/Hamtramck Assembly employs 1,600 workers.[13] In the 1990s, the city subsidized the building of a new Chrysler plant on the city's east side, Jefferson North Assembly, which employs 4,600 people. In 2009 Chrysler filed a Chapter 11 bankruptcy case, and survives in a partnership with Fiat of Italy.[14] while GM filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on June 1, 2009, and survives as a much smaller company—smaller now than Japan's Toyota Motor Corporation.[15] A little over two years after these major blows to the U.S. auto industry, the city itself went into Chapter 9 bankruptcy after years of mismanagement by local leaders.

A History of Residential Segregation by Race

During World War Two, wartime manufacturing expanded urban employment for Black job seekers who were historically underrepresented in Detroit’s labor market as labor policies sanctioned hiring discrimination.[16] Despite the expansion of employment available to Black Detroiters, racial integration within the workplace was met with fierce opposition from Blue-collar white employees. For these white Detroiters, Black employment harbored intense housing competition within Detroit’s overcrowded neighborhoods in addition to crumbling the economic stability of Detroit’s white middle class.[17] Therefore, as racial integration within the workplace alluded to racially fluid neighborhoods, the white middle class engaged in residential segregation by using discriminatory behavior and policy to regulate Black residential agency and accessibility to homeownership.[18]

Transitioning into the postwar period, the economic hardships of manufacturing industries, stemming from suburbanization, along with overpriced rental housing forced urban Black communities to fall on hard times, devolving into decrepit remnants of Detroit’s industrial surgency and booming wartime economy.[19] The mass migration of hopeful Blacks from the Jim Crow-perpetuated racism and segregation of the South into Northern neighborhoods coupled with sluggish housing construction flooded Detroit with overpopulation, limited funding, and residential mistreatment.[20] Self-serving landlords continued to prey upon vulnerable Black families through large down payments, high-interest land contracts, and high maintenance costs of living facilities. The exploitation of Black families by landlords remained absent from the political agendas of elected Detroit leaders such as Albert Cobo who defended the rights of landlords to operate their properties as they see fit.[21] Given the decentralization of manufacturing, terrible living conditions, and overpopulation, many Black Detroiters sought occupancy in more resourceful middle-class neighborhoods, but found it was not an easy process.

During the Roosevelt administration, the New Deal molded the urban landscape as a battleground of interracial hostility and residential segregation. New Deal policy sought to expand homeownership for low-income residents through the construction of federally subsidized public housing.[22] For many Americans, homeownership symbolized responsible citizenship, financial investment, and social prestige, all of which were signs of upward mobility and middle-class status.[23] However, the economic intervention of the federal government in expanding affordable housing presented a fundamental disconnect between New Deal policy and Black homeownership. This disconnect remained ingrained in the racist and classist ideologies of the white middle class that viewed public housing as a taxpayer-handout for the poor while foreseeing severe depreciation of single-family homes within neighborhoods that were the sites of public housing construction.[24] Consequently, independent homeowners inhibited the construction of New Deal sponsored public housing by using civic disorder and rioting as political tools to consolidate homeowner rejection of Black occupancy in middle-class neighborhoods. Consequently, the political dominance white homeowners assumed in Detroit’s housing disputes encouraged the Detroit Housing Commission (DHC) to establish racist policy such as the continuation of racial segregation within Detroit’s housing market, allowing the DHC to avoid the racial bloodshed of public housing construction.[25]

Additionally, New Deal policy promoted the formation of private-public partnerships to manage the allocation of federal funds within local municipalities. These private-public partnerships established residential segregation through a tactic called redlining, which restricted the movement of Black Detroiters into middle-class neighborhoods. In particular, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) effectively marked the racial boundaries of Detroit to determine the actuarial soundness of urban neighborhoods. Therefore, redlining governed the dispersal of federal loans and subsidies on the basis of the racial composition of a neighborhood. Local real estate brokers and lenders refused to allocate federal funds to predominantly Black communities such as Paradise Valley along with neighborhoods that had only a handful of Black residents as these areas were all categorized as unfit and hazardous investments for mortgages.[26] By preventing Blacks from the ability to attain mortgage loans from local banks, the New Deal private-public partnerships used redlining to protect the property values and investment opportunities for white middle-class homes. Therefore, redlining circumscribed Black homeownership in middle-class neighborhoods through the spatial and social isolation of Black Detroiters in Detroit's expanding ghettos. Simultaneously, this residential segregation also exacerbated the economic instability of Black Detroiters as these residents were forced to succumb to deteriorating housing without appreciating assets while the high rates of unemployment of Black Detroiters made them exceedingly vulnerable to losing their homes through eviction or tax foreclosure.[27]

Because the local government had the final say over the distribution of federal funds for home loan eligibility, there were no major alternatives for obtaining loans for a new home, which further promoted the precarious and unstable living conditions of Black Detroiters. The redemptive capacity of the private-public partnership between local Detroit banks and the FHA-HOLC funneled a vicious territorialism of the white middle class that upheld the high property values of white neighborhoods by unequivocally suppressing the upward mobility of Black Detroiters. Collectively, Black integration into white neighborhoods greatly depreciated property values, which further motivated white Detroiters to keep their neighborhoods segregated. Despite the creation of an affordable housing agenda that was rooted in liberal thought, Roosevelt’s New Deal underhandedly restricted the residential agency of Black Detroiters. Predicated upon a de jure system of residential segregation, New Deal policy remained tethered to the governmental imposition of societal and policy discrimination that aggravated structures of racism within Detroit’s fractured housing market.[28] In the unfolding of the housing crisis within Detroit, the federal government perpetuated the marginalization of Black Detroiters by neglecting the jarring racism and segregation that New Deal policy produced.

The theories of eugenics and racial inferiority that dictated FHA policymaking certainly translated into the FHA's subsidization of Black homeownership upon the cessation of redlining. During an era of racial liberalism, the FHA’s colorblindness and no redlining policy failed to reverse the cumulative effects of structural racism. In response to the prolonged refusal of mortgages for African Americans, the FHA passed the 1968 Housing and Urban Development Act (HUD) to encourage low-income homeownership through low-interest mortgage loans with the full financial backing of the federal government.[29] FHA-HUD policy guaranteed that pay lenders would be compensated in full for the mortgage of foreclosed homes and by creating a housing market dominated by mortgage bankers, the FHA incentivized mortgage bankers to drive desperate Black families to low-income homeownership, allowing bankers to inflate their economic gains by cycling these Black families through tax foreclosures.[30] Therefore, this racist and predatory provision of low-income housing through FHA-HUD policy elucidates that federal government was an inevitable perpetrator of racial segregation within Detroit's housing market. Despite having access to mortgage loans, Black Detroiters continued to be preyed upon by real estate bankers who earned tremendous profits from the inability of Black Detroiters to keep up with the FHA-insured mortgage payments. For many Black Detroiters, the dismissal of FHA redlining did not signal an end to the economic exploitation and residential segregation of Black families at the hands of wealth-hungry bankers and lenders. Colorblind universalism within Detroit’s housing market remained a far-fetched aspiration of Black families in their pursuit of homeownership as FHA-HUD policy failed to systematically dismantle the segregative impulses of the real estate industry.[31]

Furthermore, the threat of racial integration in white communities facilitated the rise of neighborhood associations, which were coalitions of independent white homeowners that fervently protected homeownership rights through advocacy for residential segregation. Frequently, neighborhood associations relied on restrictive covenants to mandate legal barriers to Black homeownership in middle-class neighborhoods to avoid the radical disinvestment that would stem from a racially integrated neighborhood.[32] During the legality of restrictive covenants, these deed restrictions were explicitly racist and took the form of; "people of color can't purchase this home," or only for the "Caucasian race." By leveraging the legally discriminatory capacity of restrictive covenants, neighborhood associations prioritized the stability of homeownership through the preservation of neighborhood investment and relatively high single-family home values. The homogenization of the economic and social fabric of middle-class neighborhoods reflected the white-afflicted segregation of Black Detroiters that confined these residents to Detroit's oldest and worst housing stock.[33] However, in the midst of a mid-twentieth century movement for civil rights reform, certain hallmark legal cases of discrimination in housing such as Shelley vs Kraemer deemed restrictive covenants unconstitutional. Upon this Supreme Court ruling, neighborhood associations were forced to change their restrictive zoning regulations as Black Detroiters began moving out of the dilapidated Detroit ghetto and sought residency in middle-class neighborhoods.[34] Therefore, the repealing of restrictive covenants resulted in neighborhood associations relying on extralegal subversions of restrictive covenants to alternatively stunt Black residential integration. For example, neighborhood associations amended housing contracts to now contain phrases such as “undesirable” rather than “Black” to avoid the explicit discrimination of housing based on race. These slight revisions in already racist housing contracts allowed neighborhood associations to remain legally immune during the discriminatory protection of middle-class homeownership from the perceived social disorder and housing depreciation of racially integrated neighborhoods.[35] Therefore, throughout the history of restrictive covenants, the preservation of the social and economic stability of middle-class neighborhoods hardened the residential segregation of Black Detroiters by placing restrictions on Black homeownership. Overall, restrictive covenants reinforced unequal race relations and perpetuated racial divisions that continue to exacerbate the urban inequality of current-day Detroit.[33]

Coupled with the ability of de jure discrimination to mandate residential segregation through policy, neighborhood associations curbed civil rights reform that sought to mitigate racism within housing. The middle-class mentality of neighborhood associations would govern the political climate of Detroit as this anti-integration constituency resonated with politicians who would dispel public housing and the threat of racial invasion. The 1949 mayoral election of Detroit pitted George Edwards, a UAW activist and public housing advocate, against Albert Cobo, a corporate executive and real estate investor. Cobo presented an unwavering distrust of government economic intervention and pledged to protect single-family home investment through the disapproval of federally funded public housing projects within Detroit. Therefore, the anti-public housing and pro-homeownership sentiment of Albert Cobo garnered immense support from neighborhood associations that served an indispensable role in the overwhelming victory of Cobo over Edwards for mayor of Detroit.[36]

A staunch opponent of integrated housing, mayor Cobo restructured the Mayor's Interracial Committee (MIC), a large advocate group for housing equality and civil rights reform, into the Commission on Community Relations (CCR) that more closely aligned to the anti-civil rights and segregationist political identity of neighborhood associations.[37] Additionally, Cobo enacted residential segregation and racism through DHC policy while vetoing public housing development within white neighborhoods, thus further debilitating the limited accessibility Black Detroiters had affordable housing.[38] During Cobo’s mayorship, neighborhood associations held political power within Detroit as the unregulated local government allowed for these inherently racist associations to dictate residential zoning and city planning that further strengthened the residential segregation of Black Detroiters.[35] Evidently, Cobo’s political regime displayed de facto segregation through the political mobilization of neighborhood associations and the private real-estate industry. However, the series of events that led to Cobo’s mayorship remained direct reflections of the violence launched on Black Detroiters from de jure segregation through decades of racist and classist housing policies that bled urban neighborhoods of the most basic living conditions while hardening Detroit’s racial divide.

The systematic exclusion of Black families from homeownership generationally suppressed Black Detroiters from receiving the economic assets of homeownership such as stable education, retirement, and businesses opportunities, which have created greater degrees of residential instability and precariousness. Overall, Detroit's convoluted history of segregation reveals that homeownership should not be viewed as a means to overcome poverty as exploitative market dynamics and racist housing policy eradicate the dimension of impartiality within the United States housing market.[39]

The open housing movement

In 1948, Shelley v. Kraemer and three other United States Supreme Court cases established that state enforcement of racially restrictive covenants were unconstitutional.[40] This decision revitalized the advocacy for integrated neighborhoods. Suburbs around Detroit expanded dramatically as wealthy African-Americans began to move into white neighborhoods. The singular asset that many white residents held after World War II was their home, and they feared that if Black people moved in, the value of their homes would plummet. This fear was preyed upon by blockbusting real estate agents who would manipulate Whites into selling their homes for cheap prices by convincing them that African-Americans were infiltrating the neighborhood. They would even send Black children to go door to door with pamphlets that read, "Now is the best time to sell your house—you know that." With the means to pick up and leave, many white residents fled to the surrounding suburbs. This "white flight" took much away from the city: residents, the middle class, and tax revenues which kept up public services such as schools, police, and parks. Blockbusting agents then profited by reselling these houses at incredibly marked-up prices to African-Americans desperate to get out of the inner city.[41]

These inflated prices were only affordable by the black "elite." As wealthier black Detroiters moved into the previously white neighborhoods, they left behind low-income residents in the most inadequate houses at the highest rental. Redlining, restrictive covenants, local politics, and the open housing movement all contributed to the restricted movement of black, low-income Detroiters.

1950s job losses

In the postwar period, the city had lost nearly 150,000 jobs to the suburbs. Factors were a combination of changes in technology, increased automation, consolidation of the auto industry, taxation policies, the need for different kinds of manufacturing space, and the construction of the highway system that eased transportation for commuters. Major companies like Packard, Hudson, and Studebaker, as well as hundreds of smaller companies, declined significantly or went out of business entirely. In the 1950s, the unemployment rate hovered near 10 percent.

1950s to 1960s freeway construction

By the late 1940s, the economic wounds from years of redlining and restrictive covenants hurt the standard of living for many African Americans and minorities living in Detroit. With limited housing opportunities and sky-high rents, those living in "red" neighborhoods like Black Bottom and Paradise Valley often had little financial ability to pay for private apartments or even housing repairs. Consequences of close-quarter living were exacerbated by an influx of black immigrants during the Great Migration and World War II. The decaying neighborhoods also developed sanitation problems; garbage pickups were rare and trash littered the street, accelerating the spread of diseases and enticing pests.[40] Perceptions of "urban blight" and a need for "slum clearance" in these areas were fueled especially by (majority white) Detroit city planners, who classified over two-thirds of housing in Paradise Valley as substandard.[42]

A plan for "urban renewal" in Black Bottom and Paradise Valley neighborhoods was put forth by Detroit Mayor Edward Jeffries in 1944. Utilizing eminent domain laws, the government began taking down buildings in the Black Bottom neighborhood in 1949.[43] The push for urban renewal in post-World War II Detroit was popularized by local government officials, in conjunction with real estate agents and bank owners of the time, who stood to gain from investment in new buildings and wealthier residents. When the 1956 Highway Act mandated new highways routed through Detroit, the Black Bottom and Paradise Valley areas were an ideal placement; deconstruction of the site had already been started, and the political clout of slum clearance was more powerful than the limited ability residents had to advocate against the placement.

Though it faced urban poverty and overcrowding, the Black Bottom neighborhoods were an exciting mix of culture and innovation, with the economic district boasting approximately 350 black-owned businesses.[43] The downtown area is often described as if Motown music played even from the pipes in the street. But when highway projects were announced, sometimes years before construction started and sometimes warning only thirty days in advance, the property values for those who did own land disappeared.[44] The forced relocation condemned many residents to even harsher poverty, and the local government commissions made few efforts to assist families in relocation. It was difficult enough for the thousands of persons displaced to find new housing in a time where restrictive covenants, even though technically outlawed in 1948, were deftly and covertly written into many of Detroit's surrounding neighborhoods. It was even harder for business owners to relocate their life's work. Lasting ramifications of the highway construction are still felt by the black business sector in Detroit today.

The Oakland-Hastings Freeway, now called the I-375 Chrysler Highway, was laid directly along Hastings Street at the heart of the Black Bottom business district, and cut through the Lower East Side and Paradise Valley as well.[44] For the construction of the Edsel Ford Expressway (I-94) alone, 2,800 buildings from the West Side and northern Paradise Valley were demolished, including former jazz nightclubs, churches, community buildings, businesses and homes. The Lower West Side was mostly destroyed by the John C. Lodge Freeway, which also ran through black neighborhoods outside of Twelfth Street and Highland Park.[44]

A letter from a Mrs. Grace Black found in the Bentley Historical Library's historical archives illustrates the struggles of finding housing with children in the midst of highway construction:

Sept 1950

Governor Williams:

Please consider a family of 6 who are desperately in need of a house to rent. Husband, wife, and four lonely children, who have been turned down because we have children. We are now living in a house of the Edsel Ford Express Highway. We have our notice to move on out before the 23rd of Oct. So far we haven't found a place to move. Nobody want to rent us because we have children. My children aren't destructive but nobody will give us a chance to find out if they are or not. We are so comfortable here. It's the first freedom we've enjoyed since we've had children. My husband work at children's hospital only mak $60 a week. Sixty dollars we are paying $50 a month which we don't mind because we are comfortable. This will be demolished if we were able we would buy this house. But are not. So if anything you can do will be appreciated from the depths of our hearts. You have done so much to help the lower income families. We are deeply grateful wishing you God's speed. This is urgent! Please give this your immediate consideration.

Thank you

Mrs. Grace Black (a worried mother)

I-75, Ford Field, and Comerica Park now occupy most of the area where Paradise Valley once stood. Historian Thomas Sugrue notes that of the families displaced by the razing of the Paradise Valley neighborhood:

[A]bout one-third of the Gratiot-area's families eventually moved to public housing, but 35 percent of the families in the area could not be traced. The best-informed city officials believed that a majority of families moved to neighborhoods within a mile of the Gratiot site, crowding into an already decaying part of the city, and finding houses scarcely better and often more overcrowded than that which they had left.[45]

Detroit riots

The Detroit Race Riot of 1943 broke out in Detroit in June of that year and lasted for three days before Federal troops regained control. The rioting between blacks and whites began on Belle Isle, Detroit's largest park, on June 20, 1943, and continued until June 22, killing 34, wounding 433, and destroying property valued at $2 million.[46] This was one of Detroit's worst riots, with the buildup of racial tension and animosity between blacks and whites culminating in brawls that broke out on the bridge connecting Belle Isle to southeast Detroit. Fierce attacks were launched on each others' property, including the looting of both black and white-owned stores and white rampages throughout Paradise Valley, a segregated section of Detroit that was predominantly black and very poorly maintained.[47] Because many of the Detroit police seemed to openly sympathize with the white protesters during the riot at Belle Isle, this demonstrated the underlying systemic racist attitudes prevalent during the postwar period, with institutional inequalities that perpetuated the idea of white supremacy.

As racial tensions escalated between blacks and whites, the gravity of the consequences of these tensions also escalated. Violence and riots were common, especially when regarding housing situations, as blacks began to encroach on predominantly white neighborhoods. In 1955, the black Wilson family bought a home in a white neighborhood, and soon faced vandalism and property destruction. Angry demands and threats were made at the Wilson family, harassing them to move out. Again, the Detroit police officers rarely did anything to help, choosing instead to sit in their cars nearby despite the constant harassment of the Wilsons.[48] This further reflects the white racist ideologies of the time period as they chose to ignore the blatant racism that was going on. Both the existing social constructs of racism and the political environment of the era prevented blacks from achieving equality in Detroit and greatly marginalized them.

The summer of 1967 saw five days of riots in Detroit.[49][50] Over the period of five days, forty-three people died, of whom 33 were black and 10 white. There were 467 injured: 182 civilians, 167 Detroit police officers, 83 Detroit firefighters, 17 National Guard troops, 16 State Police officers, and three U.S. Army soldiers. In the riots, 2,509 stores were looted or burned, 388 families were rendered homeless or displaced, and 412 buildings were burned or damaged enough to be demolished. Dollar losses from arson and looting ranged from $40 million to $80 million.[51]

Economic and social fallout of the 1967 riots

After the riots, thousands of small businesses closed permanently or relocated to safer neighborhoods, and the affected district lay in ruins for decades.[52]

Of the 1967 riots, politician Coleman Young, Detroit's first black mayor, wrote in 1994:

The heaviest casualty, however, was the city. Detroit's losses went a hell of a lot deeper than the immediate toll of lives and buildings. The riot put Detroit on the fast track to economic desolation, mugging the city and making off with incalculable value in jobs, earnings taxes, corporate taxes, retail dollars, sales taxes, mortgages, interest, property taxes, development dollars, investment dollars, tourism dollars, and plain damn money. The money was carried out in the pockets of the businesses and the people who fled as fast as they could. The white exodus from Detroit had been prodigiously steady prior to the riot, totally twenty-two thousand in 1966, but afterward, it was frantic. In 1967, with less than half the year remaining after the summer explosion, the outward population migration reached sixty-seven thousand. In 1968 the figure hit eighty-thousand, followed by forty-six thousand in 1969.[50]

According to the economist Thomas Sowell:

Before the ghetto riot of 1967, Detroit's black population had the highest rate of home-ownership of any black urban population in the country, and their unemployment rate was just 3.4 percent. It was not despairing that fueled the riot. It was the riot which marked the beginning of the decline of Detroit to its current state of despair. Detroit's population today is only half of what it once was, and its most productive people have been the ones who fled.[49]

However, Thomas Sugrue argues that over 20% of Detroit's adult black population was out of work in the 1950s and 1960s, along with 30% of black youth between eighteen and twenty-four.[53]

Economist Edward L. Glaeser believes the riots were a symptom of the city's already downward trajectory:

While the 1967 riots are seen as a turning point in the city’s fortunes, Detroit’s decline began in the 1950s, during which the city lost almost a tenth of its population. Powerful historical forces buffeted Detroit’s single-industry economy, and Detroit’s federally supported comeback strategies did little to help.[54]

State and local governments responded to the riot with a dramatic increase in minority hiring, including the State Police hiring blacks for the first time, and Detroit more than doubling the number of black police. The Michigan government used its reviews of contracts issued by the state to secure an increase in nonwhite employment. Between August 1967 and the end of the 1969-1970 fiscal year, minority group employment by the contracted companies increased by 21.1 percent.[55]

In the aftermath of the riot, the Greater Detroit Board of Commerce launched a campaign to find jobs for ten thousand "previously unemployable" persons, a preponderant number of whom were black. By Oct 12, 1967, Detroit firms had reportedly hired about five thousand African-Americans since the beginning of the jobs campaign. According to Sidney Fine, "that figure may be an underestimate."[56]

The Michigan Historical Review writes that "Just as the riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. facilitated the passage of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1968, which included fair housing, so the Detroit riot of July 1967, 'the worst racial disturbance' of the century to that time, provided the impetus for the passage of Michigan’s fair housing law as well as similar measures in many Michigan communities." Other laws passed in response to the disorder included "important relocation, tenants’ rights, and code enforcement legislation." Such proposals had been made by Governor Romney throughout the 1960s, but the opposition did not collapse until after the riot.[57]

1970s and 1980s

The 1970 census showed that white people still made up a majority of Detroit's population. However, by the 1980 census, white people had fled at such a large rate that the city had gone from 55 percent to 34 percent white within in a decade. The decline was even starker than this suggests, considering that when Detroit's population reached its all-time high in 1950, the city was 83 percent white.

Economist Walter E. Williams writes that the decline was sparked by the policies of Mayor Young, who Williams claims discriminated against whites.[58] By contrast, urban affairs experts largely blame federal court decisions which decided against NAACP lawsuits and refused to challenge the legacy of housing and school segregation – particularly the case of Milliken v. Bradley, which was appealed up to the Supreme Court.[59]

The District Court in Milliken had originally ruled that it was necessary to actively desegregate both Detroit and its suburban communities in one comprehensive program. The city was ordered to submit a "metropolitan" plan that would eventually encompass a total of fifty-four separate school districts, busing Detroit children to suburban schools and suburban children into Detroit. The Supreme Court reversed this in 1974. In his dissent, Justice William O. Douglas' argued that the majority's decision perpetuated "restrictive covenants" that "maintained...black ghettos." [60]

Gary Orfield and Susan E. Eaton wrote that the "Suburbs were protected from desegregation by the courts, ignoring the origin of their racially segregated housing patterns." John Mogk, an expert in urban planning at Wayne State University in Detroit, has said that "Everybody thinks that it was the riots [in 1967] that caused the white families to leave. Some people were leaving at that time but, really, it was after Milliken that you saw a mass flight to the suburbs. If the case had gone the other way, it is likely that Detroit would not have experienced the steep decline in its tax base that has occurred since then." Myron Orfield, director of the Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity at the University of Minnesota, has said:

Milliken was perhaps the greatest missed opportunity of that period. Had that gone the other way, it would have opened the door to fixing nearly all of Detroit's current problems... A deeply segregated city is kind of a hopeless problem. It becomes more and more troubled and there are fewer and fewer solutions.[61]

The departure of middle-class whites left blacks in control of a city suffering from an inadequate tax base, too few jobs, and swollen welfare rolls.[62] According to Chafets, "Among the nation’s major cities, Detroit was at or near the top of unemployment, poverty per capita, and infant mortality throughout the 1980s."[63]

Detroit became notorious for violent crime in the 1970s and 1980s. Dozens of violent black street gangs gained control of the city's large drug trade, which began with the heroin epidemic of the 1970s and grew into the larger crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s and early 1990s. There were numerous major criminal gangs that were founded in Detroit and that dominated the drug trade at various times, though most were short-lived. They included The Errol Flynns (east side), Nasty Flynns (later the NF Bangers) and Black Killers and the drug consortiums of the 1980s such as Young Boys Inc., Pony Down, Best Friends, Black Mafia Family and the Chambers Brothers.[64] The Young Boys were innovative, opening franchises in other cities, using youth too young to be prosecuted, promoting brand names, and unleashing extreme brutality to frighten away rivals.[65]

Several times during the 1970s and 1980s, Detroit was named the "arson capital of America", and the city was also repeatedly dubbed the "murder capital of America". Detroit was frequently listed by FBI crime statistics as the "most dangerous city in America" during this time frame. Crime rates in Detroit peaked in 1991, at more than 2,700 violent crimes per 100,000 people.[66] Population decline left abandoned buildings behind that became magnets for the drug trade, arson, and other criminal activity. The city's criminality has pushed tourism away from the city, and several foreign countries even issued travel warnings for the city.[66]

Around this period, in the days of the year preceding and including Halloween, Detroit citizens went on a rampage called "Devil's Night". A tradition of light-hearted minor vandalism, such as soaping windows, had emerged in the 1930s, but by the 1980s it had become, said Mayor Young, "a vision from hell." During the height of the drug era, Detroit residents routinely set fire to houses that were known as popular drug-dealing locations, accusing the city's police of being either unwilling or unable to solve the deep problems of the city.[67]

The arson primarily took place in the inner city, but surrounding suburbs were often affected as well. The crimes became increasingly destructive throughout this period. Over 800 fires were set, mostly to vacant houses, in the peak year 1984, overwhelming the city's fire department. In later years, the arsons continued, but the frequency of these fires was reduced by razing thousands of abandoned houses, buildings that were, in many cases, used to sell drugs. 5,000 of these buildings were razed in 1989–90 alone. Every year the city mobilizes "Angel's Night," with tens of thousands of volunteers patrolling high-risk areas in the city.[68][69]

Problems

Urban decay

.svg.png.webp)

Urban decay is the process where a city that was once flourishing and functioning properly falls into disuse and disrepair. Common indicators of a city in urban decay are empty plots of land, abandoned and decrepit buildings, high unemployment rates, and high crime rates. Detroit fits all of these categories and is the most famous example of urban decay in the US.[70] Detroit is often likened to a ghost town. Parts of the city are so abandoned they have been described as looking like farmland, urban prairie, and even complete wilderness.

In the 1940s, Detroit was the fourth-largest city in the US thanks in large part to the automobile industry. However, in the 1950s the automobile industry was no longer confined to Detroit. The industry began to spread out. Detroit was still the center of the industry, but many jobs left the city. More than any other city in America, Detroit has felt the negative effects of globalization.[71] Recently, there has been a major nationwide movement of people moving back into cities. However, Detroit has felt the opposite effects. Once dubbed “the blackest city in America”, Detroit now holds the name of “America’s comeback city.”

However, blight remains specifically in predominantly African American neighborhoods. A significant percentage of housing parcels in the city are vacant, with abandoned lots making up more than half of total residential lots in large portions of the city. With at least 70,000 abandoned buildings, 31,000 empty houses, and 90,000 vacant lots, Detroit has become notorious for its urban blight.

In 2010, Mayor Bing put forth a plan to bulldoze one-fourth of the city. Detroit is a metropolis that sprawls 139 square miles. In comparison, Manhattan is just over 22 square miles. The sprawling nature of the city is conducive to urban decay. The Mayor’s plan was to concentrate Detroit's remaining population into certain areas to improve the delivery of essential city services, which the city has had significant difficulty providing (policing, fire protection, trash removal, snow removal, lighting, etc.). In February 2013 the Detroit Free Press reported the Mayor's plan to accelerate the program. The project has hopes "for federal funding to replicate it [the bulldozing plan] across the city to tackle Detroit’s problems with tens of thousands of abandoned and blighted homes and buildings." Bing said the project aims "to right-size the city’s resources to reflect its smaller population." Despite this, there is still an estimated 20 square miles of empty land within the city limits.

The average price of homes sold in Detroit in 2012 was $7,500. As of January 2013, 47 houses in Detroit were listed for $500 or less, with five properties listed for $1. Despite the extremely low price of Detroit properties, most of the properties have been on the market for more than a year as the boarded-up, abandoned houses of the city are seldom attractive to buyers. The Detroit News reported that more than half of Detroit property owners did not pay taxes in 2012, at a loss to the city of $131 million (equal to 12% of the city's general fund budget).

The first comprehensive analysis of the city's tens of thousands of abandoned and dilapidated buildings took place in the spring of 2014. It found that around 50,000 of the city's 261,000 structures were abandoned, with over 9,000 structures bearing fire damage. It further recommended the demolition of 5,000 of these structures.

Between 2000 and 2010, Detroit lost a quarter of its population. More people left Detroit during this time—237,5000—than fled New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina—140,000. However, from 2010 to 2018, Detroit saw the biggest growth in racial diversity of any city analyzed by a US news study. This is not the racial diversity most other cities experienced. Opposite of the white flight most cities experienced where whites fled cities for safer suburbs, Detroit saw an influx of white residents into the downtown and midtown areas.[72] The Midtown and downtown areas have increasing population density while African American neighborhoods remain without good access to public services. The poverty rate of the city remains several times higher than the national average. Much as the city has been likened to a ghost town, it has more recently been compared to a game of Monopoly, where the economic disparity is clear and present within a few city blocks. The balance between race and capitalism plays out in Detroit in a historic fashion.

Population decline

Historically a major population center, Detroit has undergone a considerable reduction in population with the city losing over 60% of its population since 1950.[73] Detroit reached its population peak in the 1950 census at over 1.8 million people, and its population has decreased in each subsequent census. As of the 2010 census, the city has just over 700,000 residents, a total loss of 61% of its 1950 population.[74]

The vast majority of this population loss was due to the deindustrialization of Detroit that moved factories from the inner city to the suburbs. This was coupled with the phenomenon of white flight, the movement of many white families from urban areas of metro Detroit to the suburbs on the outskirts of the city. White flight was spurred on by the Great Migration, in which hundreds of thousands of blacks migrated from the South to Detroit in search of employment. This caused overcrowding in the inner city and led to racial housing segregation. Practices of redlining, mortgage discrimination, and racially restrictive covenants in Detroit further contributed to the overcrowding of certain minority groups residing in subsections of Detroit such as Black Bottom. Many of the white residents of Detroit did not wish to integrate with their black counterparts. They often chose to flee the city and reside in nicer, racially homogenous neighborhoods in the suburbs. This was also a result of an increased desire for homeownership.[42] White families were in better positions to relocate into the suburbs, in juxtaposition with blacks who faced discrimination in home loans and in the real estate market.

Highway construction post-WWII also contributed to white flight, specifically with the construction of the Interstate Highway System. This allowed white families to easily commute to work in the city from the suburbs, and incentivized many white Detroiters to thus relocate.[75] The construction of highways in Detroit further exacerbated the pre-existing racial segregation, as government officials built highways through areas that were seen as blighted – typically black "ghettos" – that were under-financed and under-maintained.

As a result of white flight and mass migration to the suburbs, a significant change in the racial composition of Detroit occurred. From 1950 to 2010, the black/white percentage of population went from 16.2%/83.6% to 82.7%/10.6%.[76] Approximately 1,400,000 of the 1,600,000 white people in Detroit after World War II left the city for the suburbs.[77] Beginning in the 1980s, for the first time in its history, Detroit was a majority black city.[78]

This drastic racial demographic change resulted in more than a change in neighborhood appearance. It had political, social, and economic effects as well. In 1974, Detroit elected its first black mayor, Coleman Young.[79] Coleman Young aimed to create a racially diverse cabinet and police force, half black and half white members, leading to a new face representing Detroit on the global stage.[79]

Most importantly, however, was the negative effect that the population decline had on Detroit's economy.[80] Following the decline in population, Detroit's tax revenue significantly decreased. The government was receiving less revenue from taxpayers residing in the city which led to more foreclosures and overall unemployment, eventually culminating in the bankruptcy of 2013.[81]

Detroit's population continues to decline today, impacting its majority poor, black demographic the hardest.[82] Because urban renewal, highway construction, and discriminatory loan policies contributed to white flight to the suburbs, the remaining poor, black city population endured radical disinvestment and a lack of public services such as dilapidated schools, a lack of safety, blighted properties, and waste, contributing the reality of families living in the city today. Furthermore, Detroit has the highest property tax of any major U.S. city, which makes it difficult for many families to afford to live in the city.[82]

White flight does appear to be reversing starting in the 1990s, with rich white families returning to the city and gentrifying areas of urban decay and blight. However, this has caused many issues with both physical and cultural displacement occurring, disproportionately impacting marginalized minority communities. Real estate development and the overall "improvement" of the city leads to increased rent in those parts of the city. Since marginalized communities tend to be more impoverished, they are not financially able to support these increased levels of rent, and therefore are physically displaced. Following physical displacement, there is also the issue of cultural displacement as gentrification causes a loss of sense of belonging, ownership, history, identity and pride associated with living in a certain place.[83]

Data does show that Detroit's population loss is slowing. The decrease in 2017 was 2,376 residents compared to the 2016 decline of 2,770.[84] The city has yet to rebound to the heights of population growth of the 1950s, but the decline is indeed slowing.

Social issues

.jpg.webp)

Unemployment

According to the U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate is at 8.4%, as of October 2017.[85] In the 20th Century, the unemployment rate was around 5% according to the U.S. Department of Labor's archives.

Poverty

The U.S.A. Census Bureau's Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012 ranks Detroit first among all 71 U.S. cities for which rates were calculated in percentage of the city's population living below the poverty level. The individual rate living below the poverty level is 36.4%; the family rate is 31.3%.[86]

Crime

Detroit has some of the highest crime rates in the United States, with a rate of 62.18 per 1,000 residents for property crimes, and 16.73 per 1,000 for violent crimes (compared to national figures of 32 per 1,000 for property crimes and 5 per 1,000 for violent crime in 2008).[87] Detroit's murder rate was 53 per 100,000 in 2012, ten times that of New York City.[88] A 2012 Forbes report named Detroit as the most dangerous city in the United States for the fourth year in a row. It cited FBI survey data that found that the city's metropolitan area had a significant rate of violent crimes: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault.[89][90]

According to Detroit officials in 2007, about 65 to 70 percent of homicides in the city were drug-related.[91] The rate of unsolved murders in the city is at roughly 70%.[92]

City finances

On March 1, 2013, Governor Rick Snyder announced that the state would be assuming financial control of the city.[93] A team was chosen to review the city's finances and determine whether the appointment of an emergency manager was warranted.[93] Two weeks later, the state's Local Emergency Financial Assistance Loan Board (ELB) appointed an emergency financial manager, Kevyn Orr.[94] Orr released his first report in mid-May.[95][96] The results were generally negative regarding Detroit's financial health.[95][96] The report said that Detroit is "clearly insolvent on a cash flow basis."[97] The report said that Detroit would finish its current budget year with a $162 million cash-flow shortfall[95][96] and that the projected budget deficit was expected to reach $386 million in less than two months.[95] The report said that costs for retiree benefits were eating up a third of Detroit's budget and that public services were suffering as Detroit's revenues and population shrink each year.[96] The report was not intended to offer a complete blueprint for Orr's plans for fixing the crisis; more details about those plans were expected to emerge within a few months.[96]

After several months of negotiations, Orr was ultimately unable to come to a deal with Detroit's creditors, unions, and pension boards[98][99] and therefore filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection in the Eastern District of Michigan U.S. Bankruptcy Court on July 18, 2013, the largest U.S. city ever to do so, with outstanding financial obligations to more than 100,000 creditors totaling approximately $18.5 billion.[100][101][102] On December 10, 2014, Detroit successfully exited bankruptcy.[103]

Resurgence

By the late 2010s, many observers, including The New York Times [104] began pointing to an economic and cultural resurgence of Detroit.[105][106] This resurgence was primarily due to private and public investment that served to revitalize the city’s social and economic dynamics. Through a combination of reinvestment and revamped social policies Detroit has achieved a renewed sense of interest and serves as a model for other areas to learn how to re-energize their urban centers.[107]

Evidence of Detroit's resurgence is most readily found in the Midtown Area and the Central Business District, which have attracted a number of high-profile investors. Most notably, Dan Gilbert has heavily invested in the acquisition and revitalization of a number of historic buildings in the Downtown area.[108] A primary focus of private real estate investment has been to position Detroit's Central Business District as an attractive site for the investment of technology companies such as Amazon, Google, and Microsoft. Approaches to the private investment of Midtown, however, have prioritized re-establishing Midtown as the cultural and commercial center of the city. Midtown Cultural Connection’s DIA Plaza Project, for instance, aims to unify the city’s cultural district—which includes the Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit Public Library, the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, and several other institutions—by constructing a public space that creates a sense of inclusion and harmony with the rest of the city.[109] Public transportation within the Downtown area has also been a target for private investors, as evidenced by Quicken Loans' investment in Detroit's QLine railcar, which currently runs a 3.3 miles (5.3 km) track along Woodward Avenue.[110]

Gilbert’s investment within the city is not limited to real estate; he has also assembled a security force that patrols the downtown area and monitors hundreds of security centers attached to buildings operated by his own Rock Ventures. These agents have eyes on almost every corner of downtown Detroit and coordinate public safety and monitor legal infractions in partnership with Wayne State University’s private police agency and Detroit’s own police force.[111] In addition to these efforts to revitalize Detroit’s social atmosphere, Gilbert and Quicken Loans have also cultivated a strong and diverse workforce within Detroit by incentivizing employees to live in Midtown and offering subsidies and loans. Through such initiatives, Gilbert has focused on “creating opportunity” for Detroiters and encouraged reinvestment within the city’s economy.[112]

However, the approach that many of these private investors have taken within the downtown area has been met with several criticisms. Many have argued that the influx of private capital into Downtown Detroit has resulted in dramatic changes to the social and socio-economic character of the city. Some claim that investors like Gilbert are converting Detroit into an oligarchical city whose redevelopment is controlled by only a few powerful figures. Residents have even referred to the downtown area as “Gilbertville” and expressed fears of physical displacement due to the increase in rent that results from such investments.[113][112] Additionally, many long-time residents fear that the influx of new capital could result in their political disempowerment and that the city government will become less responsive to their needs if it is under the influence of outside investors.[113]

Other investors, such as John Hantz, are attempting to revitalize Detroit using through another approach: urban agriculture. Unlike Gilbert, Hantz has turned his focus to the blighted neighborhoods in Detroit's residential zones. In 2008, Hantz approached Detroit's city government and proposed a plan to remove urban blight by demolishing blighted homes and planting trees to establish a large urban farm.[114] Despite fervent criticisms on behalf of city residents claiming that Hantz's proposal amounted to nothing more than a "land grab," the city government eventually approved Hantz's proposal, granting him nearly 140 acres (57 ha) of land. As of 2017, Hantz farms has planted over 24,000 saplings and demolished 62 blighted structures.[115] Still, it remains uncertain what Hantz's long-term ambitions are for the project, and many residents speculate future developments on his land.

Detroit's resurgence is also being driven by the formation of public-private-nonprofit partnerships that protect and maintain Detroit's most valuable assets. The Detroit Riverfront, for instance, is maintained and developed almost exclusively through non-profit funding in partnership with public and private enterprises. This model for economic development and revitalization has seen enormous success in Detroit, with the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy raising in excess of $23 million to revitalize and maintain riverfront assets.[116] This model for economic development is so promising that the city has turned to similar partnership strategies to manage, maintain, and revitalize a number of other city assets.

Over the past seventy years, the city of Detroit, Michigan has experienced a dramatic reduction in its population and economic wellbeing.[117] This decline has left countless members of the community in economic turmoil, driving many residents to fall behind on taxes and subsequently subject their homes to tax Foreclosure. Due to the overassessment of property values based on outdated appraisals, the property taxes on these homes are massively inflated, perpetuating further property foreclosure and Community displacement.[118] These foreclosed properties are often turned over to a public auction, where many of them are purchased by wealthy investors looking to take advantage of Detroit’s housing market.[118]

Proponents of such investment argue that wealthy investors have minimized displacement by redeveloping vacant areas in which people did not reside; however, this kind of investment can have additional repercussions, beyond the physical and economic displacement of residents. In recent years, researchers have begun considering the impacts that gentrification and radical reinvestment can have on a city’s culture. In the case of Detroit, they argue that private investment directly leads to a sense of “cultural displacement,” causing long-time residents to lose “a sense of place and community” and “may feel like their community is less their own than it used to be.” [119] Although economic reinvestment provides jobs, opportunities, and capital for the city, opponents to this agenda assert that it is just a form of “disaster capitalism” and only benefits the wealthy without including Detroit residents who have been disproportionately marginalized and excluded from progressive efforts for decades.[120] They further fear that rising property values and taxes in surrounding areas will have even more adverse impacts on existing populations and result in a new form of existential displacement.

In 2015, a group of activists started a Community land trust, or CLT, to combat this Housing crisis by providing community controlled Affordable housing while simultaneously promoting economic development.[118] The movement to implement CLTs in Detroit began with several meetings held by the Building Movement Project.[118] Detroit’s first CLT was established by a nonprofit organization named Storehouse of Hope.[121] At this time, the organization created a Go Fund Me campaign used to purchase fifteen homes which then became a part of the Community Land Trust.[118][121] The CLT works to ensure housing stability and helps residents overcome financial hardship by covering the costs of property taxes, insurance, building repairs and water bills while the residents themselves pay one third of their income in rent to the CLT.[118] Sales caps are also placed on the properties of the CLT in order to maintain affordability for generations of future buyers.[118]

Most of the skepticism surrounding CLTs is rooted in their reliance on external funding. As CLT organizations grow and their boards become more professionalized, they are often distanced from their original ideals of community-based land control which the organizations were founded upon.[122] The majority of CLTs are not built upon economically self-sustaining models, so they are forced to compete for external funding.[122] This takes away the autonomy of the CLT, as all of the power is transferred into the hands of grant funding organizations and private foundations.[122] Some believe that this problem could be avoided if CLTs could somehow source their funding from investors within the community or from funders who share their ideals of community empowerment.[122]

See also

References

- Detroit population rank is lowest since 1850, The Detroit News

- "Violent crime improving in Detroit". The Morning Sun. The Morning Sun. October 6, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/michigan/articles/2017-09-14/census-figures-show-drop-in-detroit-poverty-rate

- https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit-city/2017/09/29/detroit-police-crime-statistics/106123962/

- Hardesty, Nicole (March 23, 2011). "Haunting Images Of Detroit's Decline (Photos)". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- Sugrue, Thomas (2004). "From Motor City to Motor Metropolis: How the Automobile Industry Reshaped Urban America". Automobile in American Life andSociety. University of Michigan - Dearborn. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Sugrue, Thomas (2004). "From Motor City to Motor Metropolis: How the Automobile Industry Reshaped Urban America". Automobile in American Life and Society. University of Michigan - Dearborn. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Sugrue, Thomas (2004). "From Motor City to Motor Metropolis: How the Automobile Industry Reshaped Urban America". Automobile in American Life and Society. University of Michigan - Dearborn. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Sugrue, Thomas (2004). "From Motor City to Motor Metropolis: How the Automobile Industry Reshaped Urban America". Automobile in American Life and Society. University of Michigan - Dearborn. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Sugrue, Thomas (2004). "From Motor City to Motor Metropolis: How the Automobile Industry Reshaped Urban America". Automobile in American Life and Society. University of Michigan - Dearborn. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Sugrue, Thomas (2004). "From Motor City to Motor Metropolis: How the Automobile Industry Reshaped Urban America". Automobile in American Life and Society. University of Michigan - Dearborn. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Sugrue, Thomas (2004). "From Motor City to Motor Metropolis: How the Automobile Industry Reshaped Urban America". Automobile in American Life and Society. University of Michigan - Dearborn. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20131023104009/http://www.detroitnews.com/article/20130923/AUTO0103/309230111. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2013. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Shepardson, David (April 30, 2009). "Chrysler files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy". The Detroit News. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Welch, David (June 1, 2009). "GM Files for Bankruptcy". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 26.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 84.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 268.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 34.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 42.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 87.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 60.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 213.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 63,73.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 74,75.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 44.

- Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership. p. 260.

- Rothstein, Richard. The Color Of Law. p. XIV.

- Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership. p. 8.

- Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership. p. 18.

- Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership. p. 6.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 24.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 257.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 183.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 222.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 84.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 226.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. p. 85.

- Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership. p. 261.

- Sugrue, Thomas J. (1996). The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540: Princeton University Press. pp. 73. ISBN 978-0-691-12186-4.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Sugrue, Thomas J. (1996). The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540: Princeton University Press. pp. 36. ISBN 978-0-691-12186-4.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Sugrue, Thomas (1996). The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 37.

- Staff, Stateside. "How the razing of Detroit's Black Bottom neighborhood shaped Michigan's history". www.michiganradio.org. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- Sugrue, Thomas (December 1998). "Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit". The American Historical Review: 47. doi:10.1086/ahr/103.5.1718. ISSN 1937-5239.

- Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton University Press, 2005), p. 10

- Dominic J. Capeci, Jr., and Martha Wilkerson, "The Detroit Rioters of 1943: A Reinterpretation," Michigan Historical Review, Jan 1990, Vol. 16 Issue 1, pp. 49-72.

- Sugrue, Thomas. Origins of the Urban Crisis. p. 29.

- Sugrue, Thomas. Origins of the Urban Crisis. pp. 232–233.

- Sowell, Thomas (2011-03-29) Voting With Their Feet, LewRockwell.com

- Young, Coleman. Hard Stuff: The Autobiography of Mayor Coleman Young: p.179.

- "Michigan State Insurance Commission estimate of December, 1967, quoted in the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders AKA Kerner Report". 1968-02-09. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-24.

- Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanaugh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (1989)

- Thomas J. Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton University Press, 2000), p 261-262

- Edward L. Glaeser "In Detroit, bad policies bear bitter fruit" The Boston Globe, July 23, 2013

- Sidney Fine, Expanding the Frontier of Civil Rights: Michigan, 1948-1968 (Wayne State University Press, 2000) p. 322-327

- Sidney Fine, Expanding the Frontier of Civil Rights: Michigan, 1948-1968 (Wayne State University Press, 2000), p. 322-327

- Sidney Fine, "Michigan and Housing Discrimination 1949-1969" Michigan Historical Review, Fall 1997 Archived 2013-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Williams, Walter (December 18, 2012). "Detroit's Tragic Decline Is Largely Due To Its Own Race-Based Policies". Investor's Business Daily. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- Meinke, Samantha (September 2011). "Milliken v Bradley: The Northern Battle for Desegregation" (PDF). Michigan Bar Journal. 90 (9): 20–22. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- Milliken v. Bradley/Dissent Douglas - Wikisource, the free online library. En.wikisource.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-16.

- "Mike Alberti, "Squandered opportunities leave Detroit isolated" RemappingDebate.org". Archived from the original on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 2014-11-07.

- Heather Ann Thompson, "Rethinking the politics of white flight in the postwar city," Journal of Urban History (1999) 25#2 pp 163-98 online

- Z’ev Chafets, "The Tragedy of Detroit," New York Times Magazine July 29, 1990, p 23, reprinted in Chafets, Devil's Night: And Other True Tales of Detroit (1991).

- Carl S. Taylor (1993). Girls, gangs, women, and drugs. Michigan State University Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780870133206.

- Ron Chepesiuk (1999). The War on Drugs: An International Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 269. ISBN 9780874369854.

- "Wayne University Center for Urban Studies, October 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- Coleman Young and Lonnie Wheeler, Hard Stuff: The Autobiography of Mayor Coleman Young (1994) p 282

- Nicholas Rogers (2002). Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford University Press. pp. 98–102. ISBN 9780195168969.

- Zev Chafets, Devil's Night and Other True Tales of Detroit (1990) ch 1

- "Urban decay". www.designingbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- Wolansky, Sara Joe. "Detroit, Then and Now". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- Williams, Joseph (January 22, 2020). "A Tale of Two Motor Cities". US News.

- Angelova, Kamelia (October 2, 2012). "Bleak Photos Capture The Fall Of Detroit". Business Insider. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- Seelye, Katherine Q. (March 22, 2011). "Detroit Census Confirms a Desertion Like No Other". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- Semuels, Alana (2016-03-18). "The Role of Highways in American Poverty". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Johnson, Richard (February 1, 2013). "Graphic: Detroit Then and Now". National Post. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- Eagleton, Terry (July 2007). "Detroit Arcadia". Harpers. Retrieved April 1, 2013. - PDF version

- Darden, Thomas, Joe, Richard. Detroit: Race Riots, Racial Conflicts and the Efforts to Bridge the Racial Divide.

- Young, Coleman. Hard Stuff.

- Fletcher, Michael. "Detroit Files Largest Municipal Bankruptcy in U.S. History". Washington Post.

- Turbeville, Wallace. "The Detroit Bankruptcy". Demos.

- Beyer, Scott. "Why Has Detroit Continued to Decline?". Forbes.

- Williams, Michael (2013). Listening to Detroit: Perspectives on Gentrification in the Motor City. p. 12.

- MacDonald, Christine. "Detroit's Population Loss Slows, but Rebound Elusive". Detroit News.

- "Local Area Unemployment Statistics; Unemployment Rates for the 50 Largest Cities". U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. October 12, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- "Table 708. U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. April 19, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- "Detroit crime rates and statistics". Neighborhood Scout. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- "Detroit's homicide rate nears highest in 2 decades". Freep.com. 2013-12-23. Retrieved 2013-12-27.