Dev (mythology)

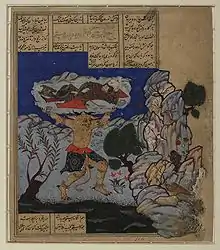

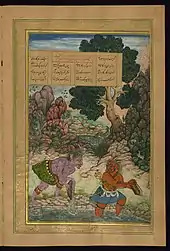

Div or dev (Persian: Dīv: دیو) are monstrous creatures in Iranian mythology, and which spread to surrounding cultures including Armenia, Turkic countries[1] and Albania.[2] Comparable to fiends or ogres,[3] they have a body similar to a human, but giant, with two horns, relishing human flesh, powerful cruel and stone-hearted with teeth like a boar.[4] Despite their physical shape, like jinn and shayatin (demons), the cause of demonic possession and insanity is ascribed to them.[5] Their natural opponents are the peri, a fairy-like spirit originated from Iranian tradition.[6] Some of them use primitive types of weapons such as stones, while others appear as warriors with armors and weapons. In addition to their physical strength, some of them are masters of sorcery, overcoming their enemies with magic.[7]

Origin

Dev probably originate from Avestan daeva, evil spirits created by the principle of evil in Zorastrianism, Ahriman. During the Islamic period, the idea of daeva changed to the notion of dev; monstrous creatures in physical shape, with long teeth and claws,[6] often compared to Western ogre.[8] The first translations of the Quran into Persian language seem to have transliterated the Quranic evil jinn as dev,[9] leading to some confusions of both distinct types of creatures.[7] Later they have been adapted by many cultures among the Islamic Ottoman Empire.

Islam

Exegesis

According to Tabari, the malicious devs are part of a long chain of pre-adamic creatures, preceding the benevolent peris, whom they fight a constant battle.[10][11] However, not all exegetes agree with that. The Islamic philosopher Al-Razi conjectured that the devs are souls of the wicked dead, turned into dev after their death.[12]

Folklore

In Persian folklore, devs are supposed to look like horned men, with animal heads and hooves. Some take the form of a snake or a dragon with multiple heads.[13] However, as shapeshifters, they can take almost every other form too. They are feared during night, the time when they are awake,[7] since it is said that darkness increases their power. Ghulam Husayn Sa’idi's Ahl-i Hava (people of the air), discussing several folkloric beliefs about different types of supernatural creatures, describes them as tall creatures living on islands or in the desert and can turn people into statues by touching them.[14]

Armenian mythology

In Armenian mythology and many various Armenian folk tales, the dev (in Armenian: դև) appears both in a kind and specially in a malicious role,[15] and has a semi-divine origin. Dev is a very large being with an immense head on his shoulders, and with eyes as large as earthen bowls.[16] Some of them may have only one eye. Usually, there are Black and White Devs. However, both of them can either be malicious or kind.

The White Dev is present in Hovhannes Tumanyan's tale "Yedemakan Tzaghike" (Arm.: Եդեմական Ծաղիկը), translated as "The Flower of Paradise". In the tale, the Dev is the flower's guardian.

Jushkaparik, Vushkaparik, or Ass-Pairika is another chimerical being whose name indicates a half-demoniac and half-animal being, or a Pairika—a female Dev with amorous propensities—that appeared in the form of an ass and lived in ruins.[16]

Persian mythology

According to the Islamic legends of Persia, the dev have been entrusted to govern the earth 70,000 years before the creation of Adam, until they had been superseded by peri and jinn ruled by Jann ibn Jann. However, when Jann ibn Jann offended heaven, an army of angels led by Iblis came down to earth, commanded by God to overthrow him. Iblis succeeded with the aid of some traitorous dev.[17] When God created the first human, Iblis and his rebellious angels refused to do homage and joined the jinn and dev, he just defeated before. His immediate followers were sent to the infernal regions of the underworld, while the rest of them were allowed to wander the earth as constant source of misery and suffering. Both Arabs and Persians located their new capital in Mount Kaf, the city of Aherman-Bad, named after Ahriman, who became their current king.[18]

References

- Karakurt, Deniz (2011). Türk Söylence Sözlüğü [Turkish Mythological Dictionary] (PDF). p. 90. ISBN 9786055618032. (OTRS: CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Elsie, Robert (2007). "Albanian Tales". In Haase, Donald (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales. Volume 1: A–F. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 24. ISBN 9780313049477. OCLC 1063874626.

- Sykes, Ella C. (27 April 1901). "Persian Folklore". Folklore. 12 (3): 261–280. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1901.9719633. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Seyed Reza Ebrahimi1 and Elnaz Valaei Bakhshayesh Manifestation of Evil in Persian Mythology from the Perspective of the Zoroastrian Religion p. 7

- Partovi, Pedram (Fall 2009). "Girls' Dormitory: Women's Islam and Iranian Horror". Visual Anthropology Review. 25 (2): 186–207. doi:10.1111/j.1548-7458.2009.01041.x.

- Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew, ed. (2016) [2014]. "Div". The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 163–166. ISBN 9781317044260. OCLC 1019829071. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "DĪV". Encyclopædia Iranica. Volume VII, Fasc. 4. 28 November 2011 [15 December 1995]. pp. 428–431. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Roux, Jean-Paul (1993). "Turkish and Mongolian Demons". In Bonnefoy, Yves (ed.). Asian Mythologies. Translated by Wendy Doniger (supervisor). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 322. ISBN 9780226064567. OCLC 26973661. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Hughes, Patrick; Hughes, Thomas Patrick (1995) [1885]. Dictionary of Islam: Being a Cyclopaedia of the Doctrines, Rites, Ceremonies, and Customs, Together with the Technical and Theological Terms of the Muhammadan Religion. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 134. ISBN 9788120606722. OCLC 35860600. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Diez, Ernst (1941). Glaube und welt des Islam (in German). Stuttgart: W. Spemann Verlag. p. 64. OCLC 1141736963. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Burton, Sir Richard, ed. (2008) [1887]. Arabian Nights, in 16 Volumes. Volume XIII: Supplemental Nights to the Book of a Thousand Nights and a Night. New York: Cosimo Classics. p. 256. ISBN 9781605206035. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Gertsman, Elina; Rosenwein, Barbara H. (2018). The Middle Ages in 50 Objects. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 103. ISBN 9781107150386. OCLC 1030592502. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Reza Yousefvand Demonology & worship of Dives in Iranian local legend Assistant Professor, Payam Noor University, Department of history, Tehran. Iran Life Science Journal 2019

- Pedram Khosronejad THE PEOPLE OF THE AIR HEALING AND SPIRIT POSSESSION IN SOUTH OF IRAN In: Shamanism and Healing Rituals in Contemporary Islam and Sufism, T.Zarcone (ed.) 2011, I.B.Tauris

- Marshall, Bonnie C. (trans.) (2007). Tashjian, Virginia A. (ed.). The Flower of Paradise and Other Armenian Tales. Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited. p. 27. ISBN 9781591583677. OCLC 231684930. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Ananikian, Mardiros Harootioon (2010). Armenian Mythology: Stories of Armenian Gods and Goddesses, Heroes and Heroines, Hells & Heavens, Folklore & Fairy Tales. Los Angeles: IndoEuropeanPublishing.com. ISBN 9781604441727. OCLC 645483426.

- Braun, Julius (1870). Gemälde der mohammedanischen Welt (in German). Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus. p. 46. OCLC 251934045.

- Smedley, Edward; William Cooke Taylor; Henry Thompson; Elihu Rich (1855). The Occult Sciences: Sketches of the Traditions and Superstitions of Past Times, and the Marvels of the Present Day. London; Glasgow: Richard Griffin & Co. p. 50. OCLC 520330. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

_capturing_an_angel_or_a_peri.jpg.webp)