Dmitry Milyutin

Count Dmitry Alekseyevich Milyutin (Russian: Дмитрий Алексеевич Милютин, tr. Dmitrij Alekseevič Miljutin; 28 June 1816, Moscow – 25 January 1912, Simeiz near Yalta) was Minister of War (1861–81) and the last Field Marshal of Imperial Russia (1898). He was responsible for sweeping military reforms that changed the face of the Russian army in the 1860s and 1870s. However, he was infamously involved in creating the framework for the genocide of Circassian Refugees from 1861 to 1865.

Dmitry Alekseyevich Milyutin | |

|---|---|

Дми́трий Алексе́евич Милю́тин Дми́трій Алексѣевичъ Милю́тинъ | |

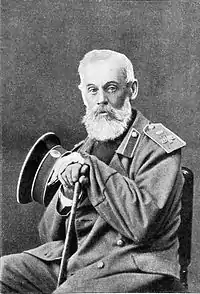

General Dmitry Milyutin in 1865 | |

| Minister of War | |

| In office 16 May 1861 – 21 May 1881 | |

| Monarch | Alexander II Alexander III |

| Preceded by | Nikolay Sukhozanet |

| Succeeded by | Pyotr Vannovsky |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 28, 1816 Moscow, Moscow Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | January 25, 1912 (aged 95) Simeiz near Yalta, Taurida Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1836-1881 |

| Rank | Field Marshal |

| Battles/wars | Caucasian War Crimean War Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878) |

| Awards | see awards |

Early career

Milyutin graduated from the Moscow University School in 1833 and Nicholas Military Academy in 1836. Unlike his brother Nikolai Milyutin, who chose to pursue a career in civil administration, Dmitry volunteered to take part in the Caucasian War (1839–45). After sustaining a grave wound, he returned to the military academy to deliver lectures as a professor.

In the following years, Milyutin earned a considerable reputation as a brilliant scholar. He emphasized the scientific value of military statistics and authored the first comprehensive study of the subject, which earned him the Demidov Prize for 1847. Milyutin regarded Suvorov as a model for military commanders and the Italian campaign of 1799 as the pinnacle of his career, elaborating these views in a detailed account of the campaign, published in five volumes in 1852 and 1853.

Capitalizing on his knowledge, Milyutin analyzed the causes of Russia's defeat in the Crimean War and framed some radical proposals for military reforms. His ideas were approved by Alexander II, who appointed Milyutin to the post of Minister of War in 1861. Several years earlier, Milyutin had taken part in the capture of Shamil, thus helping bring the prolonged Caucasian War to an end.

Minister of War

Milyutin was Minister of War from 16 May 1861 to 21 May 1881. The military reforms carried on during Milyutin's long tenure resulted in the levy system being introduced to Russia and military districts being created across the country. Military service was declared compulsory to all males aged 21 for 6 years instead of the previous 25 years. This applied to all males including nobles. The system of military education was also reformed, and elementary education was made available to all the draftees. Milyutin's reforms are regarded as a milestone in the history of Russia: they dispensed with the military recruitment and professional army introduced by Peter the Great and created the Russian army such as it continued into the 21st century until Anatoliy Serdyukov announced military reforms to end in 2020. (See: 2008 Russian military reform) Up to Dmitry Milyutin's reforms in 1874 Russian Army had no constant barracks and was billeted in dugouts and shacks.[1] The success of his reforms was demonstrated during the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878). Milyutin's subtle leadership made itself felt during the peak of the conflict when the Russians failed three times in a row to take Pleven and many experts advised them to retreat. Milyutin promptly ordered the siege to be continued in a more orderly manner which brought the war to a victorious end. At the close of the war, Milyutin set up a commission in order to investigate faulty supply of provisions and other problems that had surfaced during the siege. In recognition of his services, he was made a count and received all the Russian orders, including the Order of Saint Andrew.

Having gained the tsar's ear, Milyutin was the chief decision-maker, for ordering the deportations that he knew would cause the death from starvation and disease of large numbers of Circassians from 1861 to 1865.[2]

Later life

After the Congress of Berlin, Milyutin succeeded the ailing Chancellor Gorchakov as the leader of the imperial foreign policy. Alexander II's assassination in 1881 rendered his position precarious, however, and after Konstantin Pobedonostsev, intent on reversing the liberal innovations of the previous reign, emerged as the most powerful policy-maker, Milyutin resigned his office. In 1898, when the 80th anniversary of Alexander II was celebrated, he was promoted to Field Marshal, the first man to receive this honour for many years and the last in the history of the Russian Empire. He died in Simeiz in 1912.

Honours and awards

Domestic

- Order of St. Anna, 1st class

- Order of St. Anna, 2nd class

- Order of St. Stanislaus, 1st class

- Order of St. Stanislaus, 3rd class

- Order of St. Vladimir, 1st class

- Order of St. George, 2nd class

References

- Wiesław Caban, Losy żołnierzy powstania listopadowego wcielonych do armii carskiej, w: Przegląd Historyczny, t. XCI, z. 2, s. 245.

- Walter Richmond, The Circassian Genocide (Rutgers University Press, 2013) pp 70-71, 131-32.

- Acović, Dragomir (2012). Slava i čast: Odlikovanja među Srbima, Srbi među odlikovanjima. Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik. p. 623.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). 1906. Missing or empty

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). 1906. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Further reading

- Forrest A. Miller, Dmitrii Miliutin and the Reform Era in Russia (1968)

- Walter Richmond, The Circassian Genocide (Rutgers University Press, 2013) online

- His memoirs have been reprinted. The early years in a volume published by Oriental Research Partners (Newtonville, Mass) in 1978 with a new useful introduction by Prof. Bruce Lincoln. A three volume set of memoirs of his later years was published by Rossiiski arkhiv (Moscow 1999-2006) Pp. 525, 557, 730.

External links

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.