Principality of Montenegro

The Principality of Montenegro (Serbian: Књажевина Црна Горa / Knjaževina Crna Gora) was a former realm in Southeastern Europe that existed from 13 March 1852 to 28 August 1910. It was then proclaimed a kingdom by Nikola I, who then became King of Montenegro.

Principality of Montenegro Књажевина Црна Горa Knjaževina Crna Gora | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1852–1910 | |||||||||

.svg.png.webp) .svg.png.webp) Top: Flag (1852–1905)

Bottom: Flag (1905–1910)  Coat of arms

| |||||||||

Anthem: To Our Beautiful Montenegro | |||||||||

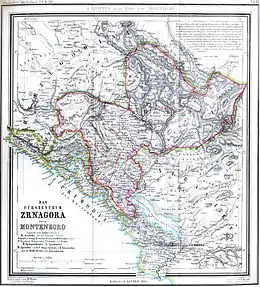

.svg.png.webp) The Principality of Montenegro in 1890. | |||||||||

| Capital | Cetinje | ||||||||

| Common languages | Serbian | ||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox | ||||||||

| Government | Principality | ||||||||

| Prince | |||||||||

• 1852–1860 (first) | Danilo I | ||||||||

• 1860–1910 (last) | Nikola I | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1879–1905 (first) | Božo Petrović-Njegoš | ||||||||

• 1907–1910 (last) | Lazar Tomanović | ||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 13 March 1852 | |||||||||

| 1 May 1858 | |||||||||

| 18 July 1876 | |||||||||

| 13 July 1878 | |||||||||

| 19 December 1905 | |||||||||

| 28 August 1910 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1852 | 5,475 km2 (2,114 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 1878 | 9,475 km2 (3,658 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1909 | 317,856 | ||||||||

| Currency | Austro-Hungarian Krone Montenegrin Perper | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The capital was Cetinje and the Montenegrin perper was used as state currency from 1906. The territory corresponded to the central area of modern Montenegro. It was a constitutional monarchy, but de facto absolutist.

Name

In Danilo I's Code, dated to 1855, he explicitly states that he is the "knjaz and gospodar of Crna Gora and Brda" (Serbian: књаз и господар Црне Горе и Брда / knjaz i gospodar Crne Gore i Brda; "prince and lord of Montenegro and Brda", "duke and lord of Montenegro and Brda").[1] In 1870, Nikola had the title of "knjaz of Crna Gora and Brda" (књаз Црне Горе и Брда / knjaz Crne Gore i Brda; "prince of Montenegro and Brda", "duke of Montenegro and Brda"), while two years later, the state was called "Knjaževina of Crna Gora" (Књажевина Црна Гора / Knjaževina Crna Gora; "Principality of Montenegro", "Duchy of Montenegro").[2]

History

Reign of Danilo

The Principality was formed on 13 March 1852 when Danilo I Petrović-Njegoš, formerly known as Vladika Danilo II, decided to renounce to his ecclesiastical position as prince-bishop and married. With the first Montenegrin constitution being proclaimed in 1855, known as "Danilo's Code". After centuries of theocratic rule, this turned Montenegro into a secular principality.

Grand Voivode Mirko Petrović, elder brother of Danilo I, led a strong army of 7,500 and won a crucial battle against the Turks (army of between 7,000 and 13,000) at Grahovac on 1 May 1858. The Turkish forces were routed. This victory forced the Great Powers to officially demarcate the borders between Montenegro and Ottoman Turkey, de facto recognizing Montenegro's centuries-long independence. Montenegro gained Grahovo, Rudine, Nikšić, more than half of Drobnjaci, Tušina, Uskoci, Lipovo, Upper Vasojevići, and part of Kuči and Dodoši tribal regions.

Reign of Nikola

After the assassination of Danilo I on 13 August 1860, Nikola I, the nephew of Danilo, became the next ruler of Montenegro. Nikola sent aid to the Serb rebels in the Herzegovina Uprising (1875–78), and then led a war against the Ottomans, the Montenegrin–Ottoman War (1876–78). The advancement of Russian forces toward Turkey forced Constantinople to sign a peace treaty on 3 March 1878, recognising the independence of Montenegro, as well as Romania and Serbia, and also increased Montenegro's territory from 4,405 km² to 9,475 km². Montenegro also gained the towns of Nikšić, Kolašin, Spuž, Podgorica, Žabljak, Bar, as well as access to the sea. This was the Great Powers' official demarcation between Montenegro and the Ottoman Empire, de facto recognizing Montenegro's independence; Montenegro was recognized by the Ottoman Empire at the Treaty of Berlin (1878). Under the rule of Nikola I, diplomatic relations were established with the Ottoman Empire. Minor border skirmishes excepted, diplomacy ushered in approximately 30 years of peace between the two states until the deposition of Abdul Hamid II.[3]

The political skills of Abdul Hamid and Nikola I played a major role on the mutually amicable relations.[3] Modernization of the state followed, culminating with the draft of a Constitution in 1905. However, political rifts emerged between the parliamentary People's Party that supported the process of democratization and union with Serbia and those of the True People's Party who were souverainist and royalist to Prince Nicholas and the Petrović-Njegoš dynasty.

Government

Flags

The historical war flags were the krstaš-barjak, plain flags with crosses in the centre. The Montenegrin war flag used in the Battle of Vučji Do (1876) was red with a white cross pattée in the centre and a white border, and this flag was adopted from the Serbian war flag in the Battle of Kosovo (1389) which found itself in Montenegro after surviving knights brought it there.[4] The same flag was used in Cetinje in 1878,[5] upon recognition of independence by the Ottoman Empire at San Stefano. According to the 1905 constitution, the national flag was a tricolour of red-blue-white,[6] which was the Pan-Slavic Serbian tricolour.[7]

Constitution of 1855

Danilo I used the Law of Petar I Petrović-Njegoš, as an inspiration for his own "General Law of the Land" from 1855, also called "Danilo I's Code" (zakonik Danila prvog). Danilo's Code was based on Montenegrin traditions and customs and it is considered to be the first national constitution in Montenegrin history. It also stated rules, protected privacy and banned warring on the Austrian Coast (Bay of Kotor). It also stated: Although there is no other nationality in this land except Serb nationality and no other religion except Eastern Orthodoxy, each foreigner and each person of different faith can live here and enjoy the same freedom and the same domestic right as Montenegrin or Highlander.

Constitution of 1905

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

At the beginning of the 20th century, political differences were starting to culminate. The country was now enlarged territorially and saw almost four decades of peace, very unusual for the country which was in war practically the whole time since it fell to Ottoman hands. The ruler, Prince Nikola I, was the longest reigning of all the Balkan dynasties, and by many perceived as the most experienced diplomat and politician. On the other hand, there was a growing population of dissatisfied young people, educated mainly abroad, who saw his rule as absolutistic and autocratic. Gathered in Belgrade, where they had support from certain political parties, they were demanding the reorganisation of government administration, constitutionalisation and the introduction of parliament. The opposition grew as their demands were supported by certain number of old military leaders and various clans' representatives. These primitive forms of nobility were mainly old and conservative, but due to their own personal antagonisms towards the prince or because of their own political ambitions, they sided with the crowd which demanded the modernisation of the country. For a long time prince and the circle of people around him defended his standpoint with the explanation that the times were not right and that Montenegrin society still hadn't evolved enough to understand the significance of constitutional monarchy. Moreover, they argued that the introduction of parliamentarism and of the political parties would again stir up the old feuds between clans and destabilise hard won unity. Neighboring Serbia by this time had already changed five constitutions and saw fifty years of political struggle between various different political parties and factions resulting in a coup and the assassination of the royal couple in 1903. Finally, Imperial Russia, the great protector of Montenegrin sovereignty in international politics and a model whose internal organisation was crudely copied by Montenegro, was still without a constitution. However, after the revolution of 1905 even Russia had to go through certain changes, thus leaving Montenegro to be the only country in Europe without a constitution alongside the Ottoman Empire, whose first constitution was short lived. Finally, after a huge media campaign against him and wide public pressure, both domestic and international, the prince at last decided to step back, so on 31 October 1905, he issued a public proclamation saying that he would grant the constitution. The proclamation also stated that he was granting the constitution of his free will and that the changes it would bring would not be radical at first because he felt that the existing institutions should be preserved from sudden changes. This caused a reply from students in Belgrade in a form of text entitled "The Word of Montenegrin University Youth", in which they criticised his intentions, saying that the new constitution would be merely formal and labeling the prince as the brake which was holding back Montenegro from modernisation and prosperity. Naturally, he did not want to give any power away or to tie his own hands in any means, so he trusted his friend Stevan Ćurčić, a conservative journalist from Serbia, with the task of writing the constitution. The outcome was the constitution that was basically a copy of the Serbian constitution from 1869 (aka The Regency Constitution) with slight changes made by the prince himself. The changes were minor but necessary adaptations for domestic circumstances. The Constitution of the Principality of Montenegro was imposed by Nikola I on 19 December (6 December on the Julian calendar) 1905 in his speech from the throne in parliament. The parliament did not get to discuss the new constitution and was dissolved right after it formally accepted it, so despite being brought in by parliament it was de facto imposed. It became remembered as the St Nicholas day constitution. It had 15 chapters with 222 articles in total. The 1905 Constitution provided state organization, type of government, the state symbols (partially), competence of the state administration, election of the statesman, the military service, the finances, and human and citizens' rights.

Montenegro is now a constitutional hereditary monarchy. Legislative power is vested in parliament as well as in the prince. The prince is the supreme commander of the armed forces, representing the state in foreign affairs. He declares war and signs the peace and alliances and also informs parliament on the matter; he has the right to appoint government officials; he is the protector of all the recognised religions in the country and he has the right of abolition and amnesty. He calls up meetings of parliament in regular and irregular sessions, opens up and closes the sessions personally, by speech from the throne or by ministry council with his decree. He has the right to dissolve parliament as well as to postpone parliamentary sessions. The dissolution decree must be countersigned by all ministers. Every adult male citizen has the right to be elected as MP, who hasn't been convicted and was not under any form of investigation, no matter the amount of taxes he pays. Active officers, NCO's and soldiers in the army did not have the right to vote. Passive suffrage is available to every citizen older than 30, who permanently resides in Montenegro, enjoys full civil rights and pays at least 15 krones of taxes. Administrative officials cannot be elected to parliament. The elections were direct, and despite the fact that the method of voting was not regulated by constitution, it was usually done publicly. The deputies were elected for a four-year term. Aside from the elected MP's, there were 14 parliament seats for the so-called virile deputies (by the position they take in the government or society). These included the Metropolitan of Montenegro, the Archbishop of Bar and Primate of Serbia, the Montenegrin Mufti, the president and the members of the State Council, the president of the High Court, the president of the Main Control and three brigadiers named by the prince himself.

No law can be passed, repealed, changed or reviewed without the acceptance of parliament. However, the initiative for the law to be passed or for the existing one to be changed can come from government to parliament or vice versa, but formal legislative projects can be made by government only. The role and the position of parliament was quite damaged by this fact. Parliament had the right to pass the budget, but for doing so it could not ask for the conditions that were not related to it. In other words, rejection of the budget cannot be used to dissolve a government, so, if parliament was to repeal the budget, the prince could extend the validness of the last year's budget to the following year. This particular example shows that the constitution did not complete the task of limiting the ruler's power. Finally, no new tax can be imposed without the agreeance of parliament.

The prince is the one who appoints and dismisses the ministers. The Ministry Council stands as the head of country's bureaucracy and is subordinated directly to the prince. For their official actions, the ministers can be held responsible by either parliament or the prince. A minister can be charged for treason, for acting against the constitution, for corruption, for damaging the state out of his own interest and if his actions are against the law in the cases set by the Law of Ministerial Responsibility. A minister can be charged by government, parliament or prince and his statute of limitations is set at five years.

State Council, composed of six members, appointed by the prince, provides the role of supreme administrative court, reviews government's legal initiatives and has jurisdiction over some subjects of financial nature. There are also high courts and municipal courts. The courts are independent in providing justice. The judges cannot be transferred without legal standpoint. The constitution also introduced local self-management through municipal courts, municipal committees and municipal assemblies. It also provided civil rights and freedom, law equality, courts jurisdiction, abolition of death penalty for purely political reasons, excluding the attempt on the life of prince or the members of the royal family. The aforementioned abolition was also not valid in cases where aside from political quilt, some other criminal action was done, as well as in cases punished by death according to military law. Right to personal property, the freedom of press and the right of assembly were also guaranteed. The constitution was followed by Penal Law (1906), Penal Procedure Law, Commerce and Obligations Law and the Lawyer's Management Law (1910).[8]

Despite all its flaws and restrictions, the Montenegrin Constitution of 1905 was an important introduction of modern liberal tendencies in European societies and of human rights and freedoms in a small patrimonial Balkan country.

Demographic history

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Montenegro |

|

| Prehistory |

| Middle Ages and early modern |

| Modern and contemporary |

- Bernard Schwartz estimated in 1882 that the Principality had 160,000 inhabitants, although a more usual estimate is that it was around 230,000 inhabitants.[9]

- In 1900, according to international sources, the Principality of Montenegro had 311,564 inhabitants. By religion, it had 293,527 Eastern Orthodox (94.21%); 12,493 Muslims (4.01%); 5,544 Roman Catholics (1.78%). 71,528 (23%) were literate.[9]

- In 1907, it had been estimated that there were around 282,000 inhabitants in Montenegro, the majority of Orthodox faith.

- In 1909 the first official census was undertaken by the authorities. According to it, there was a total of 317,856 inhabitants, although the real number was close to 220,000 inhabitants. The official language, Serbian, was used as a mother tongue by 95%, while Albanian was spoken by most of the rest. By religion, there were 94.38% Orthodox Christians, the rest being mostly Muslims and smaller numbers of Roman Catholics.

Subdivisions

The Principality of Montenegro was divided into 10 administrative divisions, called nahija (pl. nahije).

- Katunska nahija (Катунска нахија)

- Riječka nahija (Ријечка нахија)

- Crmnička nahija (Црмничка нахија)

- Primorska nahija (Приморска нахија)

- Lješanska nahija (Љешанска нахија)

- Zetska nahija (Зетска нахија)

- Brdska nahija (Брдска нахија)

- Vasojevićka nahija (Васојевићка нахија)

- Moračka nahija (Морачка нахија)

- Nikšićka nahija (Никшићка нахија)

Church

The Metropolitanate of Cetinje was divided from the state by Danilo I. It was at the time nominally Serbian Orthodox, though de jure part of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, it was largely independent. The Russian Orthodox Church uncanonically entered the Eparchy of Montenegro in their list of autocephalous churches (Sintagma, V, 1855). In 1908, the Eparchy of Zahumlje-Raška was established, existing alongside the Eparchy of Cetinje. The Metropolitans of Cetinje were: Ilarion Roganović (1876–1882), Visarion Ljubiša (1882–1884) and Mitrofan Ban (1884–1918).

References

- Stvaranje, 7–12. Obod. 1984. p. 1422.

Црне Горе и Брда историјска стварност коЈа се не може занема- рити, што се види из назива Законика Данила I, донесеног 1855. године који гласи: "ЗАКОНИК ДАНИЛА I КЊАЗА И ГОСПОДАРА СЛОБОДНЕ ЦРНЕ ГОРЕ И БРДА".

- Čedomir Popov. Istorija srpske državnosti: Srbija i Crna Gora : novovekovne srpske države. Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti. p. 254.

- Uğur Özcan, II. Abdülhamid Dönemi Osmanlı-Karadağ Siyasi İlişkileri(Political relations between the Ottoman Empire and Montenegro in the Abdul Hamid II era)Türk Tarih Kurumu, Ankara 2013. ISBN 9789751625274

- Ivanović (2006), Problematika autokefalije Mitropolije Crnogorsko-primorske,

Крсташ-барјак, познатији као вучедолска застава, је у ствари косовски крсташ-барјак, који су преживјели косовски витезови донијели у Црну Гору послије боја на Косову.

- Nenadović, Ljubomir P. (1929). O Crnogorcima: pisma sa Cetinja 1878. godine, Volume 212 (in Serbian). Štamparija "Sv. Sava,". p. 187.

- Grbovi, zastave i himne u istoriji Crne Gore. p. 66.

У члану 39. стоји: "Народне су боје: црвена плаветна и бијела". Ова уставна одредба може се сматрати првим законским утемељењем црногорске државне (народне) заставе. Претхо- дним планом (38) прописан је државни грб ...

- Ivanović, ... симболи буду засновани на тим традицијама. Државна застава Црне Горе кроз историју је била српска тробојница, што је ре- гулисано и Уставом Књажевине Црне Горе, у члану 39: "Народне боје су црвена, плаветна и бијела ..., p. 92

- http://www.montenegrina.net/pages/pages1/istorija/dokumenti/Ustav%20Crne%20Gore%20iz%201905.pdf

- Encyclopædia Britannica 1911:

In 1882 the population of Montenegro was estimated as low as 160,000 by Schwartz. A more usual estimate is 230,000. According, however, to information officially furnished at Cettigne (Cetinje), the total number of inhabitants in 1900 was 311,564, of whom 293,527 belonged to the Orthodox Church. 12,493 were Muslim and 5544 were Roman Catholics; 71,528

Sources

- Ђуро Поповић; Јован Рогановић (1899). "ЗЕМЉОПИС КЊАЖЕВИНЕ ЦРНЕ ГОРЕ за УЧЕНИКЕ III РАЗРЕДА ОСНОВНЕ ШКОЛЕ". К. Ц. Школска Комисија.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Principality of Montenegro. |