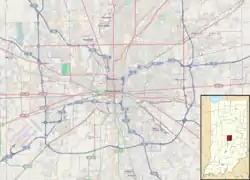

Downtown Indianapolis

Downtown Indianapolis is the central business district of Indianapolis, Indiana, United States. Downtown is the location of many corporate or regional headquarters; city, county, state and federal government facilities; several medical centers; Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis; sporting venues; performing arts venues; and most of Indianapolis' tourist attractions. Downtown is sometimes called the Mile Square, referencing the city plat developed by Alexander Ralston and Elias Pym Fordham at Indianapolis' founding. Today, Downtown encompasses about 6.5 square miles (17 km2), as designated by the City of Indianapolis' Regional Center Plan.[1]

Downtown Indianapolis | |

|---|---|

Downtown Indianapolis skyline in 2016. | |

| Nickname(s): Mile Square | |

Downtown Indianapolis  Downtown Indianapolis  Downtown Indianapolis | |

| Coordinates: 39.77°N 86.16°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| City | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6.5 sq mi (17 km2) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 28,989 |

| • Density | 4,460/sq mi (1,720/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code(s) | 46202, 46203, 46204, 46225 |

| Area code(s) | 317 and 463 |

History

Downtown Indianapolis dates to the city's founding as the state of Indiana's new capital in 1820 near the east bank of the White River. The state legislature appointed Alexander Ralston and Elias Pym Fordham to survey and design a town plan for Indianapolis, which was platted in 1821.[2] Ralston's original plan for Indianapolis called for a town of 1-square-mile (2.6 km2). Nicknamed the Mile Square, the town was bounded by North, East, South, and West Streets, although they were not named at that time, with Governor's Circle, a large circular commons, at the center of town.

Ralston's grid pattern with wide roads and public squares extended outward from the four blocks adjacent to the Circle, and also included four diagonal streets, later renamed as avenues.[3] Public squares were reserved for government and community use, but not all of these squares were used for this intended purpose.[4] Ralston altered the grid pattern in the southeast quadrant to accommodate the flow of Pogue's Run, but a plat created in 1831 changed his original design and established a standard grid there as well.[5]

Ralston's basic street plan is still evident in present-day Downtown Indianapolis.[6] Streets in the original plat were named after states that were part of the United States when Indianapolis was initially planned, with the addition of Michigan, which was a U.S. territory at that time. Tennessee and Mississippi Streets were renamed Capitol and Senate Avenues in 1895, after several state government buildings were built west of the Circle near the Indiana Statehouse. There are a few other exceptions to the early street names. The National Road, which eventually crossed Indiana into Illinois, passes through Indianapolis along Washington Street, a 120-foot-wide (37 m) east-west street (more recently converted into a one-way westbound street west of New Jersey Street) located one block south of the Circle. Meridian and Market Streets intersect the Circle. Few street improvements were made in the 1820s and 1830s; sidewalks did not appear until 1839 or 1840.[7]

In the last half of the nineteenth century, when the city's population soared from 8,091 in 1850 to 169,164 in 1900, urban development expanded in all directions as Indianapolis experienced a building boom and transitioned from an agricultural community to an industrial center.[8] Some of the city's most iconic structures were built during this period, including several that have survived to the present day in Downtown: the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument (1888, dedicated 1902), the Indiana Statehouse (1888), Union Station (1888), and the Das Deutsche Haus (1898), among others.[9]

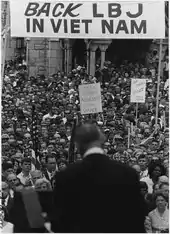

Following World War II, expansion of the American middle class, suburbanization, and declining manufacturing employment greatly impacted Downtown Indianapolis, similar to most U.S. central business districts at this time. Urban renewal projects of this era hastened the central business district's decline, particularly the clearance of working-class neighborhoods for construction of Interstate 65 and Interstate 70 in the 1960s. The extension schools of Indiana University and Purdue University merged in 1969, creating Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis and its urban campus near Indiana Avenue. Market Square Arena opened in 1974 as home to the National Basketball Association (NBA) Indiana Pacers.

.jpg.webp)

Downtown became the center of Indianapolis' aggressive sports tourism branding strategy. Throughout the 1980s, $122 million in public and private funding built the Indianapolis Tennis Center, Indiana University Natatorium, Carroll Track and Soccer Stadium, and the Hoosier Dome (later renamed the RCA Dome). The latter project secured the 1984 relocation of the NFL Baltimore Colts, the 1987 Pan American Games, and scores of subsequent athletic events of national and international interest.[10]

Modern skyscraper construction catapulted Downtown office and commercial development in the 1980s. A building boom, lasting from 1982 to 1990, saw the construction of six of the city's ten tallest buildings.[11][12] These include OneAmerica Tower (1982), Fifth Third Bank Tower (1983), Capital Center South Tower (1987), BMO Plaza (1988), Market Tower (1988), 300 North Meridian (1989), and the tallest, Salesforce Tower (1990).[13] Reinvestment continued through the 1990s, including development of White River State Park museums and attractions, Canal Walk, Circle Centre Mall (1995), Victory Field (1996), and Bankers Life Fieldhouse (1999).

Downtown Indianapolis contains 36 apartment buildings that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places in the Apartments and Flats of Downtown Indianapolis Thematic Resources.[14]

Geography

The boundaries of Downtown Indianapolis have varied over time as the city has grown. The city's original platted area, known as the Mile Square and bounded by North, South, East, and West streets, is sometimes used to denote the downtown area. However, the Regional Center Plan designated by the City of Indianapolis Department of Metropolitan Development defines the boundaries to be 16th Street on the north, Interstate 65/70 on the east, Interstate 70 on the south, and the Belt Railroad on the west, enclosing an area of 6.5 square miles (17 km2).[1]

Downtown Indianapolis is situated on flat land near the confluence of the White River and Fall Creek. Pogue's Run, a smaller tributary of the White River, flows beneath Downtown. The waterway was channeled into a sanitary tunnel in 1914.[15]

Cityscape

According to Downtown Indy, Inc., the number of apartment units in Downtown has increased 61 percent from 2011 to 2015, with more than 50 percent of new development occurring inside the Mile Square.[16] Likewise, Downtown's 2010 residential population of 17,589 is expected to more than double to 34,000 by 2018.[16]

Neighborhoods

Cultural districts

Five of seven designated Indianapolis Cultural Districts are located in Downtown, including:

Economy

Downtown Indianapolis is the largest employment cluster in the state of Indiana, with nearly 43,000 jobs per square mile (17,000/km2).[17] According to Downtown Indy, Inc., Downtown's daytime population is about 150,000.[18] According to Colliers International, the central business district commercial office market contained 11.8 million square feet (1,100,000 m2) of office space, with a direct vacancy rate of 16.9 percent in 2017.[19]

Downtown Indianapolis is home to the city's three Fortune 500 companies: health insurance company Anthem Inc. (33); pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly (141); and Simon Property Group (488), the largest real estate investment trust in the U.S.[20] Other prominent companies based Downtown include: Cummins Global Distribution Headquarters;[21] media conglomerate Emmis Communications; financial services holding company OneAmerica; the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA); local newspaper The Indianapolis Star; electricity provider Indianapolis Power & Light; and fast food restaurant chain Steak 'n Shake.

Tourism

The hospitality industry is an increasingly vital sector to the Indianapolis economy, especially Downtown. According to Visit Indy, 28.2 million visitors generated $4.9 billion in 2015, the fourth straight year of record growth.[22] Indianapolis has long been a sport tourism destination, but has more recently relied on conventions.[23] The Indiana Convention Center (ICC) and Lucas Oil Stadium are considered mega convention center facilities, with a combined 750,000 square feet (70,000 m2) of exhibition space.[24] ICC is connected to 12 hotels and 4,700 hotel rooms, the most of any U.S. convention center.[25] In 2008, the facility hosted 42 national conventions with an attendance of 317,815; in 2014, it hosted 106 for an attendance of 635,701.[23]

According to Downtown Indy, Inc., there are 34 hotels with a total of 7,839 hotel rooms.[26] Notable hotels include:

Attractions

Recent developments in downtown Indianapolis include the construction of new mid- to high-rise buildings and the $275 million expansion of the Indiana Convention Center completed in 2011.[27][28] After 12 years of planning and six years of construction, the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene & Marilyn Glick officially opened in 2013.[29] The $62.5 million public-private partnership resulted in 8 miles (13 km) of urban bike and pedestrian corridors linking six cultural districts with neighborhoods, IUPUI, and every significant arts, cultural, heritage, sports and entertainment venue downtown.[30][31][32][33] A 2015 Indiana University Policy Institute report found assessed property values along the Cultural Trail increased by over $1 billion from 2008 to 2014.[34]

Night life

Downtown's main nightlife areas are located on Meridian Street near Georgia Street and along Massachusetts Avenue. A variety of nightclubs, live music venues, bars, and restaurants are clustered along South Meridian and Georgia streets between Monument Circle and Lucas Oil Stadium. Massachusetts Avenue, or Mass Ave, lies northeast of the central business district, and is lined with high-end local bars and restaurants.

Some of the night clubs and bars in the Wholesale District include Slippery Noodle Inn, Howl at the Moon, Tiki Bob's, Claddagh Irish Pub, Kilroy's Bar and Grill, St. Elmo Steak House, and a cigar lounge called Nicky Blaines.[35] Mass Ave bars include The Eagle, Burnside Inn, Bazbeaux Pizza, Tavern on the Point, Chatterbox, Mesh on Mass, FortyFive Degrees, and Metro. Mass Ave also has various European bars that include MacNiven's (Scottish), Chatham Tap (English), and The Rathskeller (German).[36]

Venues

Athletic

- Bankers Life Fieldhouse – home to the NBA Indiana Pacers and WNBA Indiana Fever; also hosts other athletic events and concerts

- Lucas Oil Stadium – home to the NFL Indianapolis Colts and USL Indy Eleven; also hosts other athletic events, concerts, and conventions

- Indiana University Natatorium – home to IUPUI swimming; hosts national and international swimming competitions

- Michael A. Carroll Stadium – primary track and field facility for IUPUI athletics

- Victory Field – home to the International League (AAA) Indianapolis Indians

Performing arts

- Athenæum (Das Deutsche Haus) – houses the American Cabaret Theater and Young Actors Theater

- Hilbert Circle Theatre – home to the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra (ISO)

- Indiana Theatre – home to the Indiana Repertory Theatre

- Indianapolis Artsgarden

- Madam Walker Legacy Center

- Old National Centre – oldest stage house in downtown Indianapolis and the largest Shrine temple in North America.[37][38]

- Phoenix Theatre

Museums

- Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site

- Colonel Eli Lilly Civil War Museum

- Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art

- Indiana Historical Society

- Indiana State Library and Historical Bureau

- Indiana State Museum

- Indiana World War Memorial Military Museum

- James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home

- Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library

- NCAA Hall of Champions

Memorials

Other

Public art

The first instances of permanently installed public art begin in the early 1970s and include the following artworks:

- Obos by George Tsutakawa (1971)

- Untitled by Peter Mayer (1972)

- Untitled by Roland Hobart (1973)

- Color Fuses by Milton Glaser (1974)

- Quaestio Librae by Jerry Sanders (1975)

- The Runners by James McQuiston (1975)

Government

As the state capital, Indianapolis is the seat of Indiana's state government. The city has hosted the capital since its move from Corydon in 1825. The Indiana Statehouse, located Downtown, houses the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of state government, including the offices of the Governor and Lieutenant Governor of Indiana, the Indiana General Assembly, and the Indiana Supreme Court. Most state departments and agencies are located in Indiana Government Centers North and South.

The consolidated city-county government of Indianapolis and Marion County (known as Unigov) is also located Downtown at the City-County Building. The City-County Building houses the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of local government, as well as municipal departments, and the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department.

Federal field offices are located in the Birch Bayh Federal Building and United States Courthouse (which houses the United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana) and the Minton-Capehart Federal Building, both located Downtown.

Education

.jpg.webp)

Downtown is home to Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI), the third largest campus in the state based on enrollment, with 30,105 students.[39] IUPUI contains two colleges and 18 schools, including the Herron School of Art and Design, Robert H. McKinney School of Law, School of Dentistry, and the Indiana University School of Medicine, the largest medical school in the U.S.[40][41] Ball State University's R. Wayne Estopinal College of Architecture and Planning also maintains a presence in Downtown.[42]

Indianapolis Public Schools (IPS) is headquartered Downtown in the John Morton-Finney Educational Service Center. As of 2016, IPS was the second largest public school district in Indiana, serving nearly 30,000 students.[43][44]

Located Downtown, the Indianapolis Public Library's Central Library is the hub of the public library's 23 branch system, which served 4.2 million patrons and a circulation of 15.9 million materials in 2014.[45]

Transportation

Downtown Indianapolis has been the regional transportation hub for central Indiana since its establishment. The first major federally funded highway in the U.S., the National Road (now Washington Street), reached Indianapolis in 1836,[46] followed by the railroad in 1847. Indianapolis Union Station opened in 1853 as the world's first union station.[47] Citizen's Street and Railway Company was established in 1864, operating the city's first mule-drawn streetcar line.[48][49] Opened in 1904 on West Market Street, the Indianapolis Traction Terminal was the largest interurban station in the world, handling 500 trains daily and 7 million passengers annually.[50] Ultimately doomed by the automobile, the terminal closed in 1941, followed by the streetcar system in 1957.[51]

Two of the region's four interstate highways (Interstate 65 and Interstate 70) form an "inner loop" on the north, east, and south sides of downtown Indianapolis. I-65 and I-70 radiate from downtown to connect with the "outer loop," a beltway called Interstate 465. The city's address numbering system begins at the intersection of Washington and Meridian streets in downtown.[52]

The Indianapolis Public Transportation Corporation, branded as IndyGo, operates the city's public transit network, with downtown Indianapolis serving as the region's hub and spoke origin. In 2016, the Julia M. Carson Transit Center opened as the downtown hub for 27 of its 31 bus routes.[53] The Central Indiana Regional Transportation Authority (CIRTA) is a quasi-governmental agency that operates three public buses from the Julia M. Carson Transit Center to employment centers in Plainfield and Whitestown.

Downtown Indianapolis continues to be the city's intercity transportation hub. Amtrak provides intercity rail service via the Cardinal, which makes three weekly trips between New York City and Chicago. Union Station served about 30,000 passengers in 2015.[54] Three intercity bus service providers stop in the city: Greyhound Lines and Burlington Trailways (via Union Station), and Megabus (via City Market).[55]

An electric carsharing program, BlueIndy, was launched in 2015. Three of BlueIndy's six enrollment kiosks are based in downtown Indianapolis, as well as dozens of charging stations.[56]

The Indianapolis Airport Authority operates the Indianapolis Downtown Heliport, which opened for public use in 1979.

Hospitals

Several major hospitals are located in downtown Indianapolis, including:

- Sidney & Lois Eskenazi Hospital

- Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center

- Indiana University Health

All downtown medical centers are located on the Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) campus on the northwest side. Not included in this listing is Methodist Hospital, which is just outside downtown's northern boundary of 16th Street.

References

- "Region Center Plan". City of Indianapolis. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- Hyman, p. 10, and William A. Browne Jr. (Summer 2013). "The Ralston Plan: Naming the Streets of Indianapolis". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. 25 (3): 8–9.

- Massachusetts Street points diagonally to the northeast, Virginia Street to the southeast, Kentucky Street to the southwest, and Indiana Street to the northwest, beyond the Circle. See Browne, pp. 11, 16.

- A revised town plat from 1831 indicated public squares were set aside for a state university (square 25) and a state hospital (square 22). See Hale, p. 10, and Hyman, p. 10.

- Hale, p. 79.

- Indianapolis, A Walk Through Time: A Self-Guided Tour of Historic Sites in the Mile Square Area. Indianapolis: Marion County-Indianapolis Historical Society. 1996. p. 3.

- Brown, p. 25, and Browne, pp. 9–10, 17.

- Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., pp. 1481, 1486; Brown, p. 16; and Hester Ann Hale (1987). Indianapolis: The First Century. Indianapolis, IN: Marion County/Indianapolis Historical Society. p. 40. OCLC 16227635.

- Major structures constructed during this era that have been demolished include Tomlinson Hall (1883–86), a civic auditorium at Delaware and Market Street, and English's Opera House and Hotel (1880; 1884, 1896) on Monument Circle, among others. See Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., pp. 546–47; 1336–37.

- Ted Greene and Jon Sweeney (January 20, 2012). Naptown to Super City (television broadcast). Indianapolis: WFYI-TV (PBS). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- Bodenhamer, David J., and Robert G. Barrows, eds. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 28–37. ISBN 0-253-31222-1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Tallest buildings in Indianapolis". Emporis.com. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- "Salesforce Tower, Indianapolis". Emporis.com. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Higgins, Will (May 19, 2015). "Urban trekkers seek to uncover mystery of Pogue's Run". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- "2016 Downtown Living Guide". Downtown Indy, Inc. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- Klacik, Drew (September 2013). "Why Downtown Indianapolis Matters" (PDF). Indiana University Public Policy Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- "Fast Facts". Downtown Indy, Inc. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- Winkler, James (2017). "CBD Vacancy Rate Falls to Eight-Year Low" (PDF). Colliers International. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- "Fortune 500 Companies in Indiana". Fortune. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- Orr, Susan (January 5, 2017). "Cummins unveils downtown Indy office complex, recruiting tool". Indianapolis Business Journal. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- Bartner, Amy (January 24, 2017). "Visit Indy touts 4th year of record tourism". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- Schoettle, Anthony (September 25, 2015). "Expand the Indiana Convention Center again?". Indianapolis Business Journal. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- "350 Big Changes at Nation's Biggest Convention Centers" (PDF). Trade Show Executive. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- "Connected Hotels in Indianapolis". Visit Indy. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- Shuey, Mickey (April 16, 2020). "Downtown hotel occupancy fell 91% as health crisis escalated". Indianapolis Business Journal. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Downtown Indy". DowntownIndy. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Sikich, Chris (April 19, 2014). "Convention City: Convention Center's growth vaults Indy to upper tier". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- Simmons, Andrew (March 4, 2014). "In Indianapolis, a Bike Path to Progress". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- "Trail Facts". Indianapolis Cultural Trail Inc. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- Foxio (June 16, 2013). "Indianapolis Cultural Trail". Indyculturaltrail.org. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- "Project for Public Spaces". pps.org. May 10, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- "The new Indianapolis Cultural Trail is a masterpiece of bike-friendly design Cleveland should emulate". cleveland.com. Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- Burow, Sue; Majors, Jessica (March 2015). "Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 8, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Indianapolis - DOWNTOWN Night Club List". Indymotorspeedway.com. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- "Bars and Clubs in Downtown". Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2011.

- Bodenhamer, David. The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (Indiana University Press, 1994) pg.1026, 1027

- "Downtown Indy". DowntownIndy. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- "Rankings & Campus Statistics". IUPUI. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- "Schools: Academics: Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis". IUPUI. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- "Facts & Figures". IU Health. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- "CAP:INDY Connector". Ball State University. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- "Unigov Handbook: A Citizen's Guide to Local Government" (PDF). League of Women Voters of Indianapolis. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- "Indianapolis Public Schools (5385)". Indiana Department of Education. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- "Library at a Glance". Indianapolis Public Library. Archived from the original on January 9, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Baer, p. 11, and Hyman, p. 34.

- "Indianapolis Union Railroad Station". Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- Brown, p. 50.

- Sulgrove, pp. 134, 424–26.

- "Transportation in Indianapolis: then and now". Indianapolis Public Transportation Corporation. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- O'Malley, Chris (August 27, 2011). "Backer seek support for 2-mile streetcar line downtown". Indianapolis Business Journal. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- Bodenhamer, David; Barrows, Robert, eds. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p. 1485.

- Tuohy, John (June 27, 2016). "IndyGo transit center passes rush-hour test". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- "Amtrak Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2016, State of Indiana" (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- "Bus From Chicago to Indianapolis & Indianapolis to Chicago". Megabus. Archived from the original on April 12, 2016. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- Tuohy, John (January 15, 2016). "BlueIndy tops 1,000 memberships in four months". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Downtown Indianapolis. |