Intercity bus service

An intercity bus service (North American English) or intercity coach service (British English and Commonwealth English), also called a long-distance, express, over-the-road, commercial, long-haul, or highway bus or coach service, is a public transport service using coaches to carry passengers significant distances between different cities, towns, or other populated areas. Unlike a transit bus service, which has frequent stops throughout a city or town, an intercity bus service generally has a single stop at one location in or near a city, and travels long distances without stopping at all. Intercity bus services may be operated by government agencies or private industry, for profit and not for profit.[1] Intercity coach travel can serve areas or countries with no train services, or may be set up to compete with trains by providing a more flexible or cheaper alternative.

Intercity bus services are of prime importance in lightly populated rural areas that often have little or no public transportation.[2]

Intercity bus services are one of four common transport methods between cities, not all of which are available in all places. The others are by airliner, train, and private automobile.[3]

History

Stagecoaches

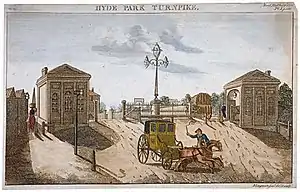

The first intercity scheduled transport service was called the stagecoach and originated in the 17th century. Crude coaches were being built from the 16th century in England, but without suspension, these coaches achieved very low speeds on the poor quality rutted roads of the time. By the mid 17th century, a basic stagecoach infrastructure was being put in place.[4] The first stagecoach route started in 1610 and ran from Edinburgh to Leith. This was followed by a steady proliferation of other routes around the country.[5]

A string of coaching inns operated as stopping points for travellers on the route between London and Liverpool by the mid 17th century. The coach would depart every Monday and Thursday and took roughly ten days to make the journey during the summer months. They also became widely adopted for travel in and around London by mid-century and generally travelled at a few miles per hour. Shakespeare's first plays were staged at coaching inns such as The George Inn, Southwark.[6]

The speed of travel remained constant until the mid-18th century. Reforms of the turnpike trusts, new methods of road building and the improved construction of coaches all led to a sustained rise in the comfort and speed of the average journey—from an average journey length of 2 days for the Cambridge-London route in 1750 to a length of under 7 hours in 1820. Robert Hooke helped in the construction of some of the first spring-suspended coaches in the 1660s and spoked wheels with iron rim brakes were introduced, improving the characteristics of the coach.[5]

In 1754, a Manchester-based company began a new service called the "Flying Coach". It was advertised with the following announcement: "However incredible it may appear, this coach will actually (barring accidents) arrive in London in four days and a half after leaving Manchester." A similar service was begun from Liverpool three years later, using coaches with steel spring suspension. This coach took an unprecedented three days to reach London with an average speed of eight miles per hour.[6]

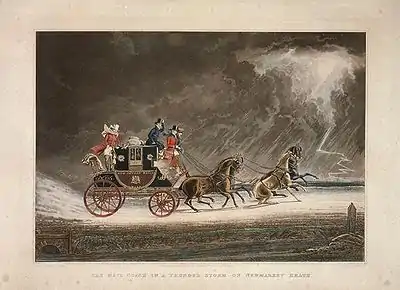

Even more dramatic improvements to coach speed were made by John Palmer at the British Post Office, who commissioned a fleet of mail coaches to deliver the post across the country.[7] His experimental coach left Bristol at 4 pm on 2 August 1784 and arrived in London just 16 hours later.[8]

The golden age of the stagecoach was during the Regency period, from 1800 to 1830. The era saw great improvements in the design of the coaches, notably by John Besant in 1792 and 1795. His coach had a greatly improved turning capacity and braking system, and a novel feature that prevented the wheels from falling off while the coach was in motion.[7] Obadiah Elliott registered the first patent for a spring-suspension vehicle. Each wheel had two durable steel leaf springs on each side and the body of the carriage was fixed directly to the springs attached to the axles.[9]

Steady improvements in road construction were also made at this time, most importantly the widespread implementation of Macadam roads up and down the country. Coaches in this period travelled at around 12 miles per hour and greatly increased the level of mobility in the country, both for people and for mail. Each route had an average of four coaches operating on it at one time - two for both directions and a further two spares in case of a breakdown en route.

Motorbuses

The development of railways in the 1830s spelt the end for the stagecoaches across Europe and America, with only a few companies surviving to provide services for short journeys and excursions until the early years of the 20th century.[10][11]

The first motor coaches were acquired by operators of those horse-drawn vehicles. W. C. Standerwick of Blackpool, England acquired its first motor charabanc in 1911,[12] and Royal Blue from Bournemouth acquired its first motor charabanc in 1913.[13] Motor coaches were initially used only for excursions.[14]

In 1919, Royal Blue took advantage of a rail strike to run a coach service from Bournemouth to London. The service was so successful that it expanded rapidly.[15] In 1920 the Minister of Transport Eric Campbell Geddes was quoted in Punch magazine as saying "I think it would be a calamity if we did anything to prevent the economic use of charabancs"[16] and expressed concern at the problems caused to small charabanc and omnibus operators in parliament.[17]

In America, Carl Eric Wickman began providing the first service in 1913. Frustrated about being unable to sell a seven-passenger automobile on the showroom floor of the dealership where he worked, he purchased the vehicle himself and started using it to transport miners between Hibbing and Alice, Minnesota. He began providing this service regularly in what would start a new company and industry.[18] The company would one day be known as Greyhound.

In 1914, Pennsylvania was the first state to pass regulations for bus service in order to prevent monopolies of the industry from forming.[19] All remaining U.S. states would soon follow.[20]

The coach industry expanded rapidly in the 1920s, a period of intense competition.[21][22] The Road Traffic Act 1930 in the UK introduced a national system of regulation of passenger road transport and authorised local authorities to operate transport services.[23] It also imposed a speed limit of 30 mph for coaches[24] whilst removing any speed limit for private cars.[25]

The 1930s to the 1950s saw the development of bus stations for intercity transport. Many expanded from simple stops into major architecturally designed terminals that included shopping and other businesses.[26] Intercity bus transport increased in speed, efficiency and popularity until the 1950s and 1960s, when as the popularity of the private automobile has increased, the use of intercity bus service has declined. For example, in Canada in the 1950s, 120 million passengers boarded intercity bus service each year; in the 1960s, this number declined to 50 million. During the 1990s, it was down to 10 million.[27]

Characteristics of intercity buses/coaches

Intercity buses, as they hold passengers for significant periods of time on long journeys, are designed for comfort. A sleeper bus is an example of a vehicle with optimum amenity for the longest travel times.

Route and operation

An intercity coach service may depart from a bus station with facilities for travellers or from a simple roadside bus stop. A coachway interchange is a term (in the United Kingdom) for a stopping place on the edge of a town, with connecting local transport. Park and ride facilities allow passengers to begin or complete their journeys by automobile. Intercity bus routes may follow a direct highway or freeway/motorway for shortest journey times, or travel via a scenic route for the enjoyment of passengers.

Intercity buses may run less frequently and with fewer stops than a transit bus service. One common arrangement is to have several stops at the beginning of the trip, and several near the end, with the majority of the trip non-stop on a highway. Some stops may have service restrictions, such as "boarding only" (also called "pickup only") and "discharge only" (also called "set-down only"). Routes aimed at commuters may have most or all scheduled trips in the morning heading to an urban central business district, with trips in the evening mainly heading toward suburbs.

Intercity coaches may also be used to supplement or replace another transport service, for example when a train or airline route is not in service.

Safety

Statistically, intercity bus service is considered to be a very safe mode of transportation. For example, in the United States there are about 0.5 fatalities per 100 million passenger miles traveled according to the National Safety Council.[28]

When accidents do occur, the large passenger capacity of buses means accidents are disastrous in their magnitude. For example, the Kempsey bus crash in Australia on 22 December 1989 involved two full tourist coaches, each travelling at 100 km/h, colliding head-on: 35 people died and 41 were injured.

Intercity coach travel by country

Canada

Intercity coach service is the only public transit to reach many urban centres in Canada, and Via Rail services are very sporadic outside the Québec City–Windsor Corridor. Coach service is mostly privately owned and operated, and following Greyhound Canada's cancellation of their Trans-Canada route, tends to be regionally focused. Major operators are listed below.

- British Columbia, Alberta: Pacific Western Transportation (Red Arrow and Ebus)

- Ontario: Greyhound Canada, Coach Canada (Megabus), GO Transit, Ontario Northland

- Quebec: Orleans Express, Intercar, Limocar

- Maritime Provinces: Maritime Bus

- Newfoundland: DRL Coachlines

China

In relatively developed regions of China where the motorway network is extensive, intercity coach is a common mean of transport between cities. In some cities, for example Shenzhen, nearly every town / district has a coach station.

Hong Kong

There are numerous inter-city coach services between Hong Kong and various cities of Guangdong Province, e.g. Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Zhongshan and Zhuhai. These kinds of coaches are legally classified as a kind of non-franchised public bus, as "International Passenger Service".[29]

In addition, there are some coach services which just carry passengers between the city of Hong Kong and the border crossing at Shenzhen, without entering the city centre in Shenzhen or further. These services are termed 'short-haul cross-boundary coach service' by the Transport Department which nearly the whole journey is within the limits of Hong Kong, as opposed to 'long-haul cross-boundary coach service' which runs between cities.

Germany

Intercity coach service in Germany became important in the decades following the Second World War, as the Deutsche Bundesbahn and the German federal post office operated numerous bus routes in major cities and metropolitan areas associated with each other. While rail was quicker and more convenient, the buses were a low-cost alternative. With the increasing prosperity of society and the growing use of the automobile, the demand fell significantly and most of these lines were abolished in the 1970s and 1980s.

One exception was traffic from and to (West-)Berlin. A long-distance bus network linking Berlin with Hamburg and several other German locations was created at the time of German division because of the small number of train services between the cities. It still exists today.

Until 2012 new long-distance bus lines could only be added in accordance with "Passenger Transportation Act" (PBefG), meaning if they did not compete with existing rail or bus lines. Since Germany - in contrast with many other European countries - has a well-developed rail network to all major cities and metropolitan areas, the domestic marketing of long-distance buses in Germany was much less significant than in many other countries.

The existing lines were often international lines as exist in almost all European countries, and for the transportation within Germany, there was a ban.[30]

In 2012, the PBefG was amended, essentially allowing intercity bus services. Thus, since 1 January 2013 Coach services have been allowed if they are longer than 50 kilometers, which led to a fast-growing market with companies like Meinfernbus, Deinbus, Flixbus, ADAC Postbus, Berlin Linien Bus GmbH and City2City.[31] Starting shortly after the establishment of the market a consolidation process occurred, which reduced the number of competing companies. ADAC Postbus became Postbus upon the ADAC leaving the cooperation. Meinfernbus and Flixbus fused to create a common company (currently the biggest operator of long-distance buses in Germany) while City2City folded operations. Deinbus came close to bankruptcy but secured an investor in time.

Greece

Since Greece's rail network was underdeveloped, intercity bus travel became important in the post-war years. The main bus operator in Greece is KTEL. It was founded in 1952.

Ireland

Generally slower than rail travel with refreshment and toilet stops required on longer routes. The main operators in the country are the Bus Éireann and private operators, such as JJ Kavanagh and Sons. The bus service between Dublin and Belfast is provided by Bus Éireann and Ulsterbus providing frequent service, including direct connections to Dublin Airport. Some bus services run overnight.

Israel

Because of the weak-developed rail network and the small size of the country and the resulting low domestic air traffic, the long-distance bus cooperative Egged is the main public transport service in the country. Because of the widespread network, Egged is considered one of the largest bus companies in the world, in part because of the long-distance bus lines. However, in recent years Israel railways has expanded and upgraded its route network and other companies have taken over routes previously served by Egged.

Netherlands

In the relatively small Netherlands there is a limited number of long-distance routes within the country. In 1994, the Interliner-network started with express buses on connections devoid of rail transport. Owing to high fares, a dense rail network and other reasons, the Interliner network fell apart into several different systems. In 2014, only a limited number of express buses existed as regular public transport usually under the name Qliner.

- 300 Groningen - Emmen Qbuzz

- 304 Groningen - Drachten Arriva

- 309 Groningen - Assen Qbuzz

- 312 Groningen - Stadskanaal Qbuzz

- 314 Groningen - Drachten Arriva

- 315 Groningen - Heerenveen - Emmeloord Arriva

- 320 Heereveen - Leeuwarden Arriva

- 322 Drachten - Oosterwolde Arriva

- 324 Groningen - Emmeloord Arriva

- 335 Bolsward - Groningen Arriva

- 350 Alkmaar - Leeuwarden Arriva

- 351 Alkmaar - Harlingen Arriva

- 355 Leeuwarden - Dokkum Arriva

- 361 Sassenheim - Schiphol Arriva

- 365 Leiden - Schiphol Arriva

- 380/381 Alphen aan den Rijn - Den Haag Arriva

- 382 Boskoop - Den Haag Arriva

- 383 Krimpen aan den Ijssel - Den Haag Arriva

- 385 Sassenheim - Den Haag Arriva

- 386 Oestgeest - Den Haag Arriva

- 387 Utrecht - Gorinchem Arriva

- 388 Utrecht - Dordrecht Arriva

Besides of regular public transport, a number of international bus companies serves Netherlands.

| Company | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Flixbus | Amsterdam | Germany, Belgium, United Kingdom, France, Switzerland, Italy, Norway, Austria, Czech Republic, Romania |

| Ouibus | Amsterdam | Belgium, United Kingdom, France, Italy, Spain |

| IC-Bus (DB, Arriva) | Amsterdam | Germany |

Norway

Norway has long-distance bus routes within the country. They operate in barely inhabited areas, including mountains, and affect the construction of a comprehensive railway network. Except in the Oslo area, Norway has only a rather sparse rail network, which extends north of the Arctic Circle to Fauske and Bodø, and to the north of Narvik with a connection to the Swedish rail network. Many of the routes are based on random railways. In addition to this network, they provide public passenger transport by many more companies within Norway than airlines, shipping lines (including the Hurtigruten) and bus lines, including many long-distance bus lines.

The buses used in the north of the country (especially in the county of Finnmark) have both a passenger compartment and a freight compartment in the rear: many remote villages are connected to the outside world only by these buses, thus achieving a large part of the cargo by bus to the city.

Pakistan

Intercity bus transportation has risen dramatically in Pakistan due to the decline of Pakistan Railways[32] and the unaffordable prices of airplanes for the average Pakistani. Numerous companies have started operating within the country such as Daewoo Express and Niazi Express, Manthar Bus Service and have gained considerable popularity due to their reliability, security and good service.[33] Smaller vans are used for transportation in the mountainous north where narrow and dangerous roads make it impossible for the movement of larger buses.

Former Yugoslavia

Intercity bus travel in Serbia, as well as in other countries of former Yugoslavia, is very popular in proportion to travel by rail and air. In some regions, data has shown that intercity bus routes have transported over ten times the number of passengers carried by intercity trains on the same competing routes.[34] It has been a trend around Serbia and the Balkan region that small towns and some villages have their own flagship bus carrier, often branded with the last name of the family whose owner runs that bus company. Belgrade, the capital of Serbia, and Zagreb, the capital of Croatia, have very large central bus terminals that operate 24 hours a day. The largest intercity bus operator in the whole region is Lasta Beograd which operates from Serbia to many countries in Europe.

Switzerland

Switzerland has an extremely dense network of interconnected rail, bus and ship lines, including some long-distance bus lines. Although Switzerland is a mountainous country, the rail network is denser than Germany's. Switzerland is an exception to the rule that long-distance bus lines are established especially in countries with inadequate railway network, or in areas with low population density. Some of the railway and main bus routes on Italian territory also serve to shorten the distance between Swiss towns. From Germany lines run from Frankfurt am Main, Heidelberg, Karlsruhe to Basel and Lucerne.

Long-distance bus services in Switzerland:

- Saas-Fee - Brig - Simplon Pass - Domodossola ("Napoleon Route" a rail connection to Locarno)

- Lugano - Menaggio on Lake Como - Tirano rail connection to St. Moritz and Chur

- St. Moritz - Chiavenna - Menaggio on Lake Como - Lugano. ("Palm Express")

- Chur - Thusis - Splügen GR - San Bernardino GR - Bellinzona

- Davos - Zernez - Mals (Malle)

- Disentis / Muster - Bellinzona

- Flüelen - Andermatt - Airolo - Bellinzona

Taiwan

Most of the time, coaches in Taiwan is driving on Controlled-access highway, so it is mainly called Highway Coach (Chinese name:國道客運). e.g. KBus(國光客運), UBus(統聯客運), HoHsin(和欣客運).

Turkey

Turkey has an extensive network of intercity buses. Every part of the country is served. The buses are popular, comfortable and frequent. For example, there are over 150 departures from Istanbul to Ankara each day. The level of onboard service is very high, with free drinks and snacks on long-distance routes. Notable operators including Pamukkale, Kâmil Koç, Metro, and Ulusoy. Tickets can be bought online from all of them.

United Kingdom

There is an extensive network of scheduled coach transport in the United Kingdom. However, passenger numbers are a fraction of those travelling by rail.[35] Coach travel companies often require passengers to purchase tickets in advance of travel, that is they may not be bought on board. The distinction between bus and coach services is not absolute, and some coach services, especially in Scotland, operate as local bus services over sections of route where there is no other bus service. National Express Coaches has operated services under that name since 1972. Megabus started in 2004 and Greyhound UK in 2009. There are many other operators. Receipts in 2004 were £1.8 billion (2008 prices) and grew significantly between 1980 and 2010. Ulsterbus connect places in Northern Ireland which are no longer on the railway network.

United States

.jpg.webp)

In the mid-1950s more than 2,000 buses operated by Greyhound Lines, Trailways, and other companies connected 15,000 cities and towns. Passenger volume decreased as a result of expanding road and air travel, and urban decay that caused many neighborhoods with bus depots to become more dangerous. In 1960, American intercity buses carried 140 million riders; the rate decreased to 40 million by 1990, and continued to decrease until 2006.[36]

By 1997, intercity bus transportation accounted for only 3.6% of travel in the United States.[37] In the late 1990s, however, Chinatown bus lines that connected New York with Boston and Philadelphia's Chinatowns began operating. They became popular with non-Chinese college students and others who wanted inexpensive transportation, and between 1997 and 2007 Greyhound lost 60% of its market share in the northeast United States to the Chinatown buses. During the following decade, new bus lines such as Megabus and BoltBus emulated the Chinatown buses' practices of low prices and curbside stops on a much larger scale, both in the original Northeast Corridor and elsewhere, while introducing yield management techniques to the industry.[36][38][39]

By 2010 curbside buses' annual passenger volume had risen by 33% and they accounted for more than 20% of all bus trips.[36] One analyst estimated that curbside buses that year carried at least 2.4 billion passenger miles in the Northeast Corridor, compared to 1.7 billion passenger miles for Amtrak trains.[38] Traditional depot-based bus lines also grew, benefiting from what the American Bus Association called "the Megabus effect", akin to the Southwest Effect,[36] and both Greyhound and its subsidiary Yo! Bus, which competed directly with the Chinatown buses, benefited after the federal government shut several Chinatown lines down in June 2012.[39]

Between 2006 and 2014, American intercity buses focused on medium-haul trips between 200 and 300 miles; airplanes performed the bulk of longer trips and automobiles shorter ones. For most medium-haul trips curbside bus fares were less than the cost of automobile gasoline, and one tenth that of Amtrak. Buses are also four times more fuel-efficient than automobiles. Their Wi-Fi service is also popular; one study estimated that 92% of Megabus and BoltBus passengers planned to use an electronic device.[36] New lower fares introduced by Greyhound on traditional medium-distance routes and rising gasoline prices have increased ridership across the network and made bus travel cheaper than all alternatives.

Effective June 25, 2014, Greyhound reintroduced many much longer bus routes, including New York–Los Angeles, Los Angeles–Vancouver, and others, while increasing frequencies on existing long-distance and ultra-long-distance buses routes. This turned back the tide of shortening bus routes and puts Greyhound back in the position of competing with long-distance road trips, airlines, and trains. Long-distance buses were to have Wi-Fi, power outlets, and extra legroom, sometimes extra recline, and were to be cleaned, refueled, and driver-changed at major stations along the way, coinciding with Greyhound's eradication of overbooking. It also represented Greyhound's traditional bus expansion over the expansion of curbside bus lines.[40]

Safety on U.S. intercity buses

On August 4, 1952, Greyhound Lines had its deadliest accident when two Greyhound buses collided head-on along then-U.S. Route 81 near Waco, Texas. The fuel tanks of both buses then ruptured, bursting into flames. Of the 56 persons aboard both coaches, 28 were killed, including both drivers.[41][42]

On May 9, 1980, a freight ship collided with the Sunshine Skyway Bridge, resulting in several vehicles, including a Greyhound bus, falling into the Tampa Bay. All 26 people on the bus perished, along with nine others. This is the largest loss of life on a single Greyhound coach to date.

On March 5, 2010, a bus operated by Tierra Santa Inc. crashed on Interstate 10 in Arizona, killing six and injuring sixteen passengers. The bus was not carrying insurance, and had also been operating illegally because the company had applied for authority to operate an interstate bus service, but had failed to respond to requests for additional information.[43][44]

Security on U.S. intercity buses

Though generally rare, various incidents have occurred over time involving both drivers and passengers on intercity buses.

Security became a concern following the September 11 attacks. Less than a month later, on October 3, 2001, Damir Igric, a passenger on a Greyhound bus, slit the throat of the driver, killing Igric, and six other passengers as the bus crashed. It was determined there was no connection between the September 11 attacks and this incident. Nevertheless, this raised concern.

On September 30, 2002, another Greyhound driver was assaulted near Fresno, California, resulting in two passenger deaths after the bus then rolled off an embankment and crashed.[45] Following this attack, driver shields were installed on most Greyhound buses that now prevent passengers from directly having contact the driver while the bus is in motion, even if the shield is forced open. On buses which do not have the shield, the seats directly behind the driver are generally off limits.[46]

The growing popularity in the United States of new bus lines such as Megabus and BoltBus that pick up and drop off passengers on the street instead of bus depots has led to a rise in the perceived security of intercity buses. Megabus states that a quarter of its passengers are unaccompanied women.[36]

Urban-suburban bus line

Urban-suburban bus line is generally categorized as public transit, especially for large metropolitan transit networks. Usually these routes cover a long distance compared to most transit bus routes, but still short—usually 40 miles in one direction. An urban-suburban bus line generally connects a suburban area to the downtown core.

The vehicle can be something as simple as a merely refitted school bus (which sometimes already contains overhead storage racks) or a minibus. Often a suburban coach may be used, which is a standard transit bus modified to have some of the functionality of an interstate coach. An example would be the Suburban line employed by TransLink (Vancouver), typically going from the downtown core of Vancouver to suburban cities such as Delta and White Rock. In such case, the vehicles are modified standard transit bus, but with only one door and air conditioning. The vehicles provide accommodation for the disabled (through a lift or ramp at the front), and thus has a few high-back seats, usually in the front, that can be folded up for wheelchairs. The rest of the seats are reclining upholstered seats and have individual lights and overhead storage bins. Because it is a commuter bus, it has some (but not much) standing room, stop-request devices, and a farebox. This model also has a bike rack at the front to accommodate two bicycles.

Some lines use a full-size interstate coach with on board toilet, such as the "TrainBus" service of Vancouver's West Coast Express commuter rail system. Suburban models in the United States are often used in Park-and-Ride services, and are very common in the New York City area, where New Jersey Transit Bus Operations is a major operator serving widespread bedroom communities.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Intercity buses. |

References

- Traffic and Highway Engineering By Nicholas J. Garber, Lester A. Hoel, page 46

- Effective Approaches to Meeting Rural Intercity Bus Transportation Needs - Google Books. 2002. ISBN 9780309067638. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- Transportation Statistics Annual Report (1997) edited by Marsha Fenn, page 175

- "History of transport and travel".

- M. G. Lay (1992). Ways of the World: A History of the World's Roads and of the Vehicles That Used Them. Rutgers University Press. p. 125.

- "Coaching History". Archived from the original on 2018-05-04. Retrieved 2014-01-12.

- "The Mail Coach Service" (PDF). The British Postal Museum & Archive. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-01-02. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- The Postman and the Postal Service, Vera Southgate, Wills & Hepworth Ltd, 1965, England

- Adams, William Bridges (1837). English Pleasure Carriages. London: Charles Knight & Co.

- Anderson, R.C.A. and Frankis, G. (1970) History of Royal Blue Express Services David & Charles Chapter 1

- Dyos, H. J. & Aldcroft, D.H. (1969) British Transport, an economic survey Penguin Books, p.225

- "W.C. Standerwick: 1911-1974". www.petergould.co.uk.

- Anderson, R.C.A. and Frankis, G. (1970) History of Royal Blue Express Services David & Charles p.28

- Anderson and Frankis (1970) p.32

- Anderson & Frankis, p.41

- "Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 159, August 18th, 1920 by Various".

- "Corporation Profits Tax". Hansard.

Mr. BILLING: the poor people who cannot afford a motor-car and who go out occasionally in charabancs—are being taxed £84 a year, according to the seating capacity. Is the right hon. Gentleman aware that that represents about 25 per cent. greater than the capital cost of the vehicle?... The MINISTER of TRANSPORT (Sir E. Geddes): Will the hon. Gentleman send me a workable scheme?

- The streamline era Greyhound terminals: the architecture of W.S. Arrasmith By Frank E. Wrenick, page 99

- The best transportation system in the world: railroads, trucks, airlines ... By Mark H. Rose, Bruce Edsall Seely, Paul F. Barrett, page 46

- Deregulation and the future of intercity passenger travel, John Robert Meyer, Clinton V. Oster, p. 169

- Flitton, D.(2004) 50 Years of South Midland Paul Lacey ISBN 0-9510739-8-2, p.41

- The best transportation system in the world: railroads, trucks, airlines ... By Mark H. Rose, Bruce Edsall Seely, Paul F. Barrett, page 45

- "The initial crisis of bus service licensing 1931–34" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- "Before The London Transport Identity". Bus World. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- "Speeding". UK Motorists. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- Suburbanizing the masses: public transport and urban development in ... By Colin Divall, Winstan Bond, pages 270, 285

- Making public transport work By Mark Bunting, page 13

- "Visions for the Future..." Dec. 6, 2007 by the Passenger Rail Working Group quotes "National Safety Council Injury Facts 2002", p. 128

- "Transport Department - Brief description of NFB services". Archived from the original on 2015-12-31. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- "Jahrzehnte auf der Standspur: - WELT". DIE WELT.

- Personenbeförderungsgesetz: § 42a Personenfernverkehr

- "Decline of Pakistan Railways... By Sundus". Paktribune.

- "The System of Local Buses in Pakistan". 9 December 2011.

- Subotica.com (Serbian): AUTOBUS POPULARNIJI OD VOZA. Retrieved January 25, 2013

- Statistics Travel Division (2008-04-01). "Public Transport: UK National Statistics Publication Hub". Statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-11-13. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- Austen, Ben (2011-04-07). "The Megabus Effect". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Retrieved May 17, 2013.

- Transportation Statistics Annual Report (1997) edited by Marsha Fenn, page 7

- O'Toole, Randal (29 June 2011). "Intercity Buses: The Forgotten Mode". Policy Analysis (680).

- Schliefer, Theodore (2013-08-08). "Bus travel is picking up, aided by discount operators". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- "Greyhound System Timetable June 25th, 2014". Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- Carlton Jackson, "Hounds of the Road", accessed November 2, 2008

- Allen Richards, "My Turn: He's still walking tall, and grateful to be alive" Archived 2010-04-13 at the Wayback Machine, Daily Breeze, October 21, 2008, accessed Nov. 2, 2008

- "6 Dead in Fatal Arizona Bus Crash". CBS News. March 5, 2010.

- "Bus in fatal Arizona crash operating illegally". CNN. March 6, 2010.

- Knife attack on California bus BBC.co.uk, October 1, 2002, date accessed: May 28, 2008

- Greyhound faces lawsuits over '01 wreck Passengers say line kept quiet about attacks on drivers, from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, accessed May 28, 2008