Dry cleaning

Dry cleaning is any cleaning process for clothing and textiles using a solvent other than water. The modern dry cleaning process was developed and patented by Thomas L. Jennings.[1]

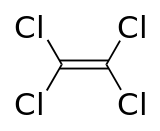

Dry cleaning still involves liquid but is so named because the term 'wet' is specific to water; clothes are instead soaked in a water-free liquid solvent, tetrachloroethylene (perchloroethylene), known in the industry as "perc", which is the most widely used solvent. Alternative solvents are 1-bromopropane and petroleum spirits.[2]

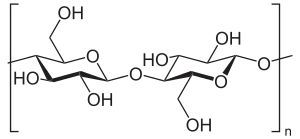

Most natural fibers can be washed in water but some synthetics (e.g., viscose, lyocell, modal, and cupro) react poorly with water and must be dry-cleaned.[3][4]

History

Thomas L. Jennings is the inventor and first to patent the commercial dry cleaning process known as "dry scouring", on March 3, 1821 (Patent Number: US 3,306X).[5] He was the first African-American to be granted a patent of any kind, although there were attempts to prevent him; opponents claimed that the nature of the process was dangerous.

An early adopter of commercial "dry laundry" using turpentine was Jolly Belin in Paris in 1825.[6] Modern dry cleaning's use of non-water-based solvents to remove soil and stains from clothes was reported as early as 1855. The potential for petroleum-based solvents was recognized by French dye-works operator Jean Baptiste Jolly, who offered a new service that became known as nettoyage à sec—i.e., dry cleaning.[7][8] Flammability concerns led William Joseph Stoddard, a dry cleaner from Atlanta, to develop Stoddard solvent (white spirit) as a slightly less flammable alternative to gasoline-based solvents. The use of highly flammable petroleum solvents caused many fires and explosions, resulting in government regulation of dry cleaners. After World War I, dry cleaners began using chlorinated solvents. These solvents were much less flammable than petroleum solvents and had improved cleaning power.

Shift to tetrachloroethylene

By the mid-1930s, the dry cleaning industry had adopted tetrachloroethylene (perchloroethylene), or PCE for short, as the solvent. It has excellent cleaning power and is nonflammable and compatible with most garments. Because it is stable, tetrachloroethylene is readily recycled.[2]

Infrastructure

Dry cleaning businesses, from the perspective of the customer, are either plants or drop shops.[9] A plant does on-site cleaning.[9] A drop shop receives garments from customers, sends them to a large plant, and then has the cleaned garment returned to the shop for collection by the customer.[9] The turnaround time is longer for a drop shop than for a local plant.[9] However, running a plant requires more work for the business owner.[9] Since 2010, in some markets, web apps have been used to schedule low-cost home delivery for dry cleaning.[9]

This cycle minimized the risk of fire or dangerous fumes created by the cleaning process. At this time, dry cleaning was carried out in two different machines—one for the cleaning process, and the second to remove the solvent from the garments.

Machines of this era were described as vented; their drying exhausts were expelled to the atmosphere, the same as many modern tumble-dryer exhausts. This not only contributed to environmental contamination but also much potentially reusable PCE was lost to the atmosphere. Much stricter controls on solvent emissions have ensured that all dry cleaning machines in the Western world are now fully enclosed, and no solvent fumes are vented to the atmosphere. In enclosed machines, solvent recovered during the drying process is returned condensed and distilled, so it can be reused to clean further loads or safely disposed of. The majority of modern enclosed machines also incorporate a computer-controlled drying sensor, which automatically senses when all detectable traces of PCE have been removed. This system ensures that only small amounts of PCE fumes are released at the end of the cycle.

Mechanism

In terms of mechanism, dry cleaning selectively solubilizes stains on the article. The solvents are non-polar and tend to selectively extract compounds that cause stains. These stains would otherwise only dissolve in aqueous detergents mixtures at high temperatures, potentially damaging delicate fabrics.

Non-polar solvents are also good for some fabrics, especially natural fabrics, as the solvent does not interact with any polar groups within the fabric. Water binds to these polar groups which results in the swelling and stretching of proteins within fibers during laundering. Also, the binding of water molecules interferes with weak attractions within the fiber, resulting in the loss of the fiber's original shape. After the laundry cycle, water molecules will dry off. However, the original shape of the fibers has already been distorted and this commonly results in shrinkage. Non-polar solvents prevent this interaction, protecting more delicate fabrics.

The usage of an effective solvent coupled with mechanical friction from tumbling effectively removes stains.

Process

A dry-cleaning machine is similar to a combination of a domestic washing machine and clothes dryer. Garments are placed in the washing or extraction chamber (referred to as the 'basket' or 'drum'), which constitutes the core of the machine. The washing chamber contains a horizontal, perforated drum that rotates within an outer shell. The shell holds the solvent while the rotating drum holds the garment load. The basket capacity is between about 10 and 40 kg (22 to 88 lb).

During the wash cycle, the chamber is filled approximately one-third full of solvent and begins to rotate, agitating the clothing. The solvent temperature is maintained at 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit), as a higher temperature may damage it. During the wash cycle, the solvent in the chamber (commonly known as the 'cage' or 'tackle box') is passed through a filtration chamber and then fed back into the 'cage'. This is known as the cycle and is continued for the wash duration. The solvent is then removed and sent to a distillation unit consisting of a boiler and condenser. The condensed solvent is fed into a separator unit where any remaining water is separated from the solvent and then fed into the 'clean solvent' tank. The ideal flow rate is roughly 8 liters of solvent per kilogram of garments per minute, depending on the size of the machine.

Garments are also checked for foreign objects. Items such as plastic pens may dissolve in the solvent bath, damaging the textiles. Some textile dyes are "loose" and will shed dye during solvent immersion. Fragile items, such as feather bedspreads or tasseled rugs or hangings, may be enclosed in a loose mesh bag. The density of perchloroethylene is around 1.7 g/cm3 at room temperature (70% heavier than water), and the sheer weight of absorbed solvent may cause the textile to fail under normal force during the extraction cycle unless the mesh bag provides mechanical support.

Not all stains can be removed by dry cleaning. Some need to be treated with spotting solvents — sometimes by steam jet or by soaking in special stain-remover liquids — before garments are washed or dry cleaned. Also, garments stored in soiled condition for a long time are difficult to bring back to their original color and texture.

A typical wash cycle lasts for 8–15 minutes depending on the type of garments and degree of soiling. During the first three minutes, solvent-soluble soils dissolve into the perchloroethylene and loose, insoluble soil comes off. It takes 10–12 minutes after the loose soil has come off to remove the ground-in insoluble soil from garments. Machines using hydrocarbon solvents require a wash cycle of at least 25 minutes because of the much slower rate of solvation of solvent-soluble soils. A dry cleaning surfactant "soap" may also be added.

At the end of the wash cycle, the machine starts a rinse cycle where the garment load is rinsed with freshly distilled solvent dispensed from the solvent tank. This pure solvent rinse prevents discoloration caused by soil particles being absorbed back onto the garment surface from the 'dirty' working solvent.

After the rinse cycle, the machine begins the extraction process, which recovers the solvent for reuse. Modern machines recover approximately 99.99% of the solvent employed. The extraction cycle begins by draining the solvent from the washing chamber and accelerating the basket to 350–450 rpm, causing much of the solvent to spin free of the fabric. Until this time, the cleaning is done in normal temperature, as the solvent is never heated in dry cleaning process. When no more solvent can be spun out, the machine starts the drying cycle.

During the drying cycle, the garments are tumbled in a stream of warm air (60–63 °C/140–145 °F) that circulates through the basket, evaporating traces of solvent left after the spin cycle. The air temperature is controlled to prevent heat damage to the garments. The exhausted warm air from the machine then passes through a chiller unit where solvent vapors are condensed and returned to the distilled solvent tank. Modern dry cleaning machines use a closed-loop system in which the chilled air is reheated and recirculated. This results in high solvent recovery rates and reduced air pollution. In the early days of dry cleaning, large amounts of perchlorethylene were vented to the atmosphere because it was regarded as cheap and believed to be harmless.

After the drying cycle is complete, a deodorizing (aeration) cycle cools the garments and removes further traces of solvent, by circulating cool outside air over the garments and then through a vapor recovery filter made from activated carbon and polymer resins. After the aeration cycle, the garments are clean and ready for pressing and finishing.

Solvent processing

Working solvent from the washing chamber passes through several filtration steps before it is returned to the washing chamber. The first step is a button trap, which prevents small objects such as lint, fasteners, buttons, and coins from entering the solvent pump.

Over time, a thin layer of filter cake (called "muck") accumulates on the lint filter. The muck is removed regularly (commonly once per day) and then processed to recover solvent trapped in the muck. Many machines use "spin disk filters", which remove the muck from the filter by centrifugal force while it is back washed with solvent.

After the lint filter, the solvent passes through an absorptive cartridge filter. This filter, which contains activated clays and charcoal, removes fine insoluble soil and non-volatile residues, along with dyes from the solvent. Finally, the solvent passes through a polishing filter, which removes any soil not previously removed. The clean solvent is then returned to the working solvent tank. Cooked powder residue is the name for the waste material generated by cooking down or distilling muck. It will contain solvent, powdered filter material (diatomite), carbon, non-volatile residues, lint, dyes, grease, soils, and water. The waste sludge or solid residue from the still contains solvent, water, soils, carbon, and other non-volatile residues. Used filters are another form of waste as is waste water.

To enhance cleaning power, small amounts of detergent (0.5–1.5%) are added to the working solvent and are essential to its functionality. These detergents emulsify hydrophobic soils and keep soil from redepositing on garments. Depending on the machine's design, either an anionic or a cationic detergent is used.

Symbols

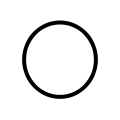

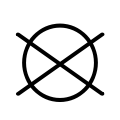

The international GINETEX laundry symbol for dry cleaning is a circle. It may have the letter P inside it to indicate perchloroethylene solvent, or the letter F to indicate a flammable solvent (Feuergefährliches Schwerbenzin). A bar underneath the circle indicates that only mild cleaning processes is recommended. A crossed-out empty circle indicates that dry cleaning is not permitted.[10]

Professional cleaning symbol

Professional cleaning symbol.svg.png.webp) Dry clean, hydrocarbon solvent only (HCS)

Dry clean, hydrocarbon solvent only (HCS)s.svg.png.webp) Gentle cleaning with hydrocarbon solvents

Gentle cleaning with hydrocarbon solventsss.svg.png.webp) Very gentle cleaning with hydrocarbon solvents

Very gentle cleaning with hydrocarbon solvents.svg.png.webp) Dry clean, tetrachloroethylene (PCE) only

Dry clean, tetrachloroethylene (PCE) onlys.svg.png.webp) Gentle cleaning with PCE

Gentle cleaning with PCEss.svg.png.webp) Very gentle cleaning with PCE

Very gentle cleaning with PCE Do not dry clean

Do not dry clean

Solvents used

Perchloroethylene

Perchloroethylene (PCE, or tetrachloroethylene) has been in use since the 1930s. PCE is the most common solvent, the "standard" for cleaning performance. It is a highly effective cleaning solvent. It is thermally stable, recyclable, and has low toxicity. It can, however, cause color bleeding/loss, especially at higher temperatures. In some cases it may damage special trims, buttons, and beads on some garments. It is better for oil-based stains (which account for about 10% of stains) than more common water-soluble stains (coffee, wine, blood, etc.). The toxicity of tetrachloroethylene "is moderate to low" and "Reports of human injury are uncommon despite its wide usage in dry cleaning and degreasing".[11]

Hydrocarbons

Hydrocarbons are represented by products such as Exxon-Mobil's DF-2000 or Chevron Phillips' EcoSolv, and Pure Dry. These petroleum-based solvents are less aggressive but also less effective than PCE. Although combustible, risk of fire or explosion can be minimized when used properly. Hydrocarbons are however pollutants. Hydrocarbons retain about 10-12% of the market.

Trichloroethylene

Trichloroethylene is more aggressive than PCE but is very rarely used. With superior degreasing properties, it was often used for industrial workwear/overalls cleaning in the past. TCE is classified as carcinogenic to humans by the United States Environmental Protection Agency.[12]

Supercritical CO2

Supercritical CO2 is an alternative to PCE; however, it is inferior in removing some forms of grime.[13] Additive surfactants improve the efficacy of CO2.[14] Carbon dioxide is almost entirely nontoxic. The greenhouse gas potential is also lower than that of many organic solvents.

The dry cleaning process involves charging a sealed chamber which is loaded with clothes using gaseous carbon dioxide from a storage vessel to approximately 200 to 300 psi. This step in the process is initiated as a precaution to avoid thermal shock to the cleaning chamber. Liquid carbon dioxide is then pumped into the cleaning chamber from a separate storage vessel by a hydraulic, or electrically driven pump (which preferably has dual pistons). The pump increases the pressure of the liquid carbon dioxide to approximately 900 to 1500 psi. A separate sub-cooler reduces the temperature of the carbon dioxide by 2 to 3 degrees Kelvin below the boiling point in an effort to prevent cavitation which could lead to premature degradation of the pump. [15]

Consumer Reports rated supercritical CO2 superior to conventional methods, but the Drycleaning and Laundry Institute commented on its "fairly low cleaning ability" in a 2007 report.[16] Supercritical CO2 is, overall, a mild solvent which lowers its ability to aggressively attack stains.

One deficiency with supercritical CO2 is that its electrical conductivity is low. As mentioned in the Mechanisms section, dry cleaning utilizes both chemical and mechanical properties to remove stains. When solvent interacts with the fabric's surface, the friction dislocates dirt. At the same time, the friction also builds up an electrical charge. Fabrics are very poor conductors and so usually, this build-up is discharged through the solvent. This discharge does not occur in liquid carbon dioxide and the build-up of an electrical charge on the surface of the fabric attracts the dirt back on to the surface, which diminishes its cleaning efficiency. To compensate for the poor solubility and conductivity of supercritical carbon dioxide, research has focused on additives. For increased solubility, 2-propanol has shown increased cleaning effects for liquid carbon dioxide as it increases the ability of the solvent to dissolve polar compounds.[17]

Machinery for use of supercritical CO2 is expensive—up to $90,000 more than a PCE machine, making affordability difficult for small businesses. Some cleaners with these machines keep traditional machines on-site for more heavily soiled textiles, but others find plant enzymes to be equally effective and more environmentally sustainable.

Other solvents: niche, emerging, etc.

For decades, efforts have been made to replace PCE. These alternatives have not proven economical thus far:

- Stoddard solvent – flammable and explosive, 100 °F/38 °C flash point

- CFC-113 (Freon-113), a CFC. Now banned as ozone-unfriendly.

- Decamethylcyclopentasiloxane ("liquid silicone"), called D5 for short. It was popularized by GreenEarth Cleaning.[18] It is more expensive than PCE. It degrades within days in the environment.

- Dibutoxymethane (SolvonK4) is a bipolar solvent that removes water-based stains and oil-based stains.[19]

- Brominated solvents (n-propyl bromide, Fabrisolv, DrySolv) are solvents with higher KB-values than PCE. This allows faster cleaning, but can damage some synthetic beads and sequins if not used correctly. Healthwise, there are reported risks associated with nPB such as numbness of nerves.[20] The exposure to the solvents in a typical dry cleaner is considered far below the levels required to cause any risk.[21] Environmentally, it is approved by the U.S. EPA. It is among the more expensive solvents, but it is faster cleaning, lower temperatures, and quick dry times.

References

- "Thomas Jennings". National Inventors Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- David C. Tirsell "Dry Cleaning" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2000. doi:10.1002/14356007.a09_049

- Hunter, Jennifer (22 May 2019). "Dry Cleaning Your Wool Sweaters? Don't Bother". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Zubair, Rashid (10 January 2021). "Is Dry Cleaning better than washing". Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- "US Patent: 3,306X". Directory of American Tool and Machinery Patents. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- Hasenclever, Kaspar D (2001). "Dry Cleaning - Treatment of Textiles in Solvent". In Wypych, George (ed.). Handbook of Solvents. ChemTec Publishing. p. 883. ISBN 9781895198249.

- "How Dry Cleaning Works". Science.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 2006-03-30.

- "How To Start a Laundry / Dry Cleaning Business in Nigeria". Jalingo.co. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- Lee, Sunny (1 October 2019). "The uncertain future of your neighborhood dry cleaner". The Outline. Retrieved 2019-10-11.

- "Professional textile care symbols". GINETEX - Swiss Association for Textile Labelling. Archived from the original on 2013-05-28. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- E.-L. Dreher; T. R. Torkelson; K. K. Beutel (2011). "Chlorethanes and Chloroethylenes". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.o06_o01. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- EPA Releases Final Health Assessment for TCE September 2011. Accessed 2011-09-28.

- "Dry-cleaning with CO2 wins award [Science] Resource". Resource.wur.nl. 2010-10-12. Archived from the original on 2012-03-12. Retrieved 2013-03-14.

- "How can we use carbon dioxide as a solvent?". Contemporary topics in school science. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- "Liquid/supercritical carbon dioxide/dry cleaning system". 1993-12-06. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

- Drycleaning and Laundry Institute. "The DLI White Paper: Key Information on Industry Solvents." The Western Cleaner & Launderer, August 2007.

- , Townsend, Carl W.; Sidney C. Chao & Edna M. Purer, "Liquid carbon dioxide cleaning system employing a static dissipating fluid"

- Tarantola, Andrew. "There's a Better Way to Dry Clean Your Clothes". Gizmodo. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- Ceballos, Diana M.; Whittaker, Stephen G.; Lee, Eun Gyung; Roberts, Jennifer; Streicher, Robert; Nourian, Fariba; Gong, Wei; Broadwater, Kendra (2016). "Occupational exposures to new dry cleaning solvents: High-flashpoint hydrocarbons and butylal". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. 13 (10): 759–769. doi:10.1080/15459624.2016.1177648. PMC 5511734. PMID 27105306.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "HAZARD EVALUATION 1-Bromopropane" Archived 2013-11-06 at the Wayback Machine July 2003. Accessed 2014-Jan-22

- Azimi Pirsaraei, S. R.; Khavanin, A; Asilian, H; Soleimanian, A (2009). "Occupational exposure to perchloroethylene in dry-cleaning shops in Tehran, Iran". Industrial Health. 47 (2): 155–9. doi:10.2486/indhealth.47.155. PMID 19367044.

External links

- Hazard Summary provided by the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

- NIOSH Safety and Health Topic: Drycleaning