Dura-Europos

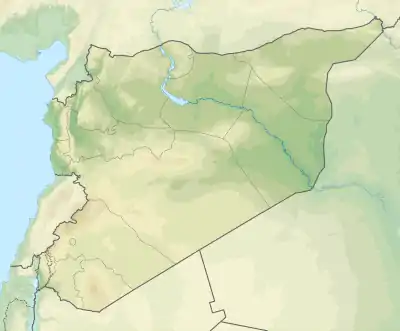

Dura-Europos (Greek: Δοῦρα Εὐρωπός), also spelled Dura-Europus, was a Hellenistic, Parthian and Roman border city built on an escarpment 90 metres (300 feet) above the right bank of the Euphrates river. It is located near the village of Salhiyé, in today's Syria. In 113 BC, Parthians conquered the city, and held it, with one brief Roman intermission (114 AD), until 165 AD. Under Parthian rule, it became an important provincial administrative centre. The Romans decisively captured Dura-Europos in 165 AD and greatly enlarged it as their easternmost stronghold in Mesopotamia, until it was captured by the Sasanian Empire after a siege in 256–57 AD. Its population was deported, and after it was abandoned, it was covered by sand and mud and disappeared from sight.

Temple of Bel at Dura-Europos | |

Shown within Syria  Dura-Europos (Near East) | |

| Location | near Salhiyah, Syria |

|---|---|

| Region | Middle East |

| Coordinates | 34.747°N 40.730°E |

| Type | settlement |

| Area | Syrian Desert |

| History | |

| Material | Various |

| Founded | c. 300 BC |

| Abandoned | 256–257 AD |

| Periods | Classical antiquity |

| Cultures | Hellenistic, Parthian, Roman |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1922–1937 1986–present |

| Archaeologists | James Henry Breasted Franz Cumont Michael Rostovtzeff Pierre Leriche |

| Condition | Destroyed during the Syrian Civil War |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | No, closed due to the war |

|

|

|

c. 300 BC

[+187 years] c. 113 BC

c. 65–19 BC

[+80 years] c. 33 BC

[+16 years] c. 17–16 BC

[+133 years] AD 116

[+5 years] AD 121

[+39 years] AD 160

[+4 years] AD 164

c. AD 168–171

c. AD 165–200

[+47 years] 'c. AD 211

post-AD 216

[+13 years] c. AD 224

c. AD 232–256

[+14 years] AD 238

[+2 years] c. AD 240

c. AD 244–254

[+13 years] AD 253

post-AD 254

[+3 years] AD 256–257 |

Dura-Europos is extremely important for archaeological reasons. As it was abandoned after its conquest in 256–57 AD, nothing was built over it and no later building programs obscured the architectonic features of the ancient city. Its location on the edge of empires made for a co-mingling of cultural traditions, much of which was preserved under the city's ruins. Some remarkable finds have been brought to light, including numerous temples, wall decorations, inscriptions, military equipment, tombs, and even dramatic evidence of the Sassanian siege.

It was looted and mostly destroyed between 2011 and 2014 by the Islamic State during the Syrian Civil War.[4][5]

History

Originally a fortress,[6] it was founded in 303 BC with the name Dura by Seleucus I Nicator on the intersection of an east-west trade route and the trade route along the Euphrates.[7] Dura controlled the river crossing on the route between his newly founded cities of Antioch and Seleucia on the Tigris. Its rebuilding as a great city built after the Hippodamian model, with rectangular blocks defined by cross-streets ranged round a large central agora, was formally laid out in the 2nd century BC. The traditional view of Dura-Europos as a great caravan city is becoming nuanced by the discoveries of locally made manufactures and traces of close ties with Palmyra (James). Instead, Dura Europos owed its development to its role as a regional capital.[6]

In 113 BC, the Iranian Parthians conquered Dura-Europos, and held it, with one brief intermission, until 165 AD, when it was taken by the Romans.[8][9][10][11][12] The Parthian period was a phase of expansion at Dura Europos—an expansion favored by abandonment of the town's military function. All the space enclosed by the walls gradually became occupied, and the installation of new inhabitants with Semitic and Iranian names alongside descendants of the original Macedonian colonists contributed to an increase in the population,[6] which was a multicultural one, as inscriptions in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, various Aramaic dialects (Hatran, Palmyrene, Syriac), and also Middle Persian, Parthian, and Safaitic testify. In the 1st century BC, it served as a frontier fortress of the Parthian Empire.[13]

The entirely original architecture of Dura Europos was perfected during the Parthian period. This period was characterized by a progressive evolution of Greek concepts toward new formulas in which regional traditions, particularly Babylonian ones, played an increasing role. These innovations affected both religious and domestic buildings. Although Iranian influence is difficult to find in the architecture of Dura Europos, in figurative art the influence of Parthian art is evident.[6]

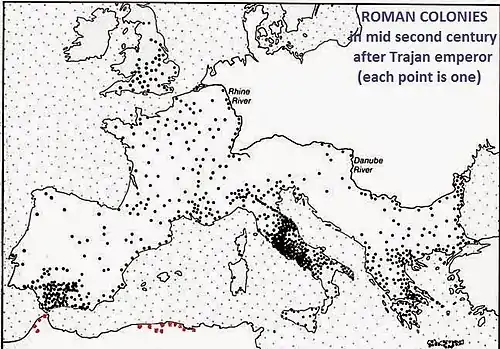

In 114 AD, the Emperor Trajan occupied the city for a couple of years: the Third Cyrenaica legion erected a "Triumphal Arch" to the west of the Gate of Palmyra. Upon the death of Trajan in 117, Rome relinquished Mesopotamia to the Parthians. Dura was retaken by the Roman army of Lucius Verus during the Roman–Parthian War of 161–166.[8][9][10][11]

The townspeople however retained considerable freedom as a regional headquarters for the section of the river between the Khabur and modern Abu Kemal.[11] As historian Ross Burns states, in exchange the city's military role was abandoned. Its population, originally based on the Greek settler element, were increasingly outnumbered by people of Semitic stock and by the first century BC, the city was predominantly eastern in character.[11] The Romans called the city by the name Dura Europus, because the local aristocracy was composed of Macedonian descendants (identifying that the city was ruled by "Europeans" from Macedonia).

Romans used the city as a starting point for the conquest of the territories of Osroene and as outpost for expeditions against the Parthian empire and their Tigris capital in 198 AD. The city later was a border post of the Roman "Kingdom of Palmyra".

In A.D. 194, Emperor Septimius Severus divided the province of Syria to limit the power of its previously rebellious governors. As a result, Dura became part of the new province of Syria Coele. In its later years, it also attained the status of a Roman colonia, which, by the third century, was what James (Henry Breasted) calls an “honorary title for an important town.” He suggests that the “Roman authorities wanted to present Dura as an important city of the Roman province.”

— Dura-Europos: Crossroad of Cultures by Carly Silver[14]

The military importance of the site was confirmed after 209 AD: the northern part of the site was occupied by a Roman camp, isolated by a brick wall; soldiers housed between the civilians, among others in the so-called "House of Scribes". Romans built the palace of the commander of the military region, on the edge of a cliff. The city then has several sanctuaries beside the temples dedicated to the Greek gods (Zeus and Artemis); there were shrines dedicated to Mithra, to Palmyrene gods and local deities (Aphlad, Azzanathkôna) dating from the 1st century AD.

In 211 AD the emperor Septimius Severus granted the title of "Colonia" to Dura Europos.

Later in 216 AD, a small amphitheater for soldiers was built in the military area, while the new synagogue, completed in 244 AD, and a house of Christians were embellished with frescos of important characters wearing Roman tunics, caftans and Parthian trousers. These splendid paintings that cover the walls testify to the richness of the Jewish and Christian community. The population of Dura Europos, at the rate of 450–650 houses grouped to eight per island, is estimated at about 5000 people per maximum.

Around 256 AD, the city was taken by the Sassanids led by Shapur I, who deported the entire surviving population after killing all the Roman defenders.

The good state of preservation of these buildings and their frescoes was due to their location, close to the main city wall facing west, and the military necessity to strengthen the wall. The Sassanid Persians had become adept at tunneling under such walls in order to undermine them and create breaches. As a countermeasure the Roman garrison decided to sacrifice the street and the buildings along the wall by filling them with rubble to bolster the wall in case of a Persian mining operation, so the Christian chapel, the synagogue, the Mithraeum and many other buildings were entombed. They also buttressed the walls from the outside with an earthen mound forming a glacis and sealed it with a casing of mud brick to prevent erosion.

There is no written record of the siege of Dura. However, the archaeologists uncovered quite striking evidence of the siege and how it progressed.[15]

The buttressing of the walls would be tested in AD 256 when Shapur I besieged the city. True to the fears of the defenders, Shapur set his engineers to undermine what archaeologists called Tower 19, two towers north of the Palmyrene Gate. When the Romans became aware of the threat, they dug a countermine with the aim of meeting the Persian effort and attack them before they could finish their work. The Persians had already dug complex galleries along the wall by the time the Roman countermine reached them. They managed to fight off the Roman attack, and when the city defenders noticed the flight of soldiers from the countermine, it was quickly sealed. The wounded and stragglers were trapped inside, where they died. (It was the coins found with these Roman soldiers that dated the siege to AD 256.) The countermine was successful, for the Persians abandoned their operations at Tower 19.

Next, the Sassanids attacked Tower 14, the southernmost along the western wall. It overlooked a deep ravine to the south and it was from that direction that it was attacked. This time the mining operation was successful in that it caused the tower and adjacent walls to subside. However the Roman countermeasure which bolstered the wall prevented it from collapsing.

This brought a third approach to entering the city. A ramp was raised again attacking Tower 14, but, as it was being built and the garrison fought to stop the progress of the ramp, another mine was started near the ramp. Its purpose was not to cause a collapse of the wall — the buttress had been successful — but to pass under it and penetrate the city. This tunnel was built to allow the Persians four abreast to move through it. It eventually entered the city and pierced the inner embankment and, when the ramp was completed, Dura's end had come. As Persian troops charged up the ramp, their counterparts in the tunnel would have invaded the city with little opposition, as nearly all the defenders would have been on the wall attempting to repel the attack from the ramp. The few city survivors would have been marched off to Ctesiphon and there sold as slaves. The city was eventually abandoned.

In January 2009, researchers claimed they had found evidence that the Persian Empire used poisonous gases at Dura against the Roman defenders during the siege. Excavations at Dura have discovered the remains of 19 Roman and 1 Persian soldiers at the base of the city walls.[16] An archaeologist at the University of Leicester suggested that bitumen and sulphur crystals were ignited to create poisonous gas, which was then funnelled through the tunnel with the use of underground chimneys and bellows.[17] The Roman soldiers had been constructing a countermine, and Sassanian forces are believed to have released the gas when their mine was breached by the Roman countermine. The lone Persian soldier discovered among the bodies is believed to be the individual responsible for releasing the gas before the fumes overcame him as well.[18]

Archaeology

The existence of Dura-Europos was long known through literary sources. It was rediscovered by the American "Wolfe Expedition" in 1885, when the Palmyrene Gate was photographed by John Henry Haynes.[19]

British troops under Capt. Murphy in the aftermath of World War I and the Arab Revolt also explored the ruins. On March 30, 1920, a soldier digging a trench uncovered brilliantly fresh wall-paintings in the Temple of Bel. The American archeologist James Henry Breasted, then at Baghdad, was alerted. Major excavations were carried out in the 1920s and 1930s by French and American teams. The first archaeology on the site, undertaken by Franz Cumont and published in 1922–23, identified the site with Dura-Europos, and uncovered a temple, before renewed hostilities in the area closed it to archaeology. Later, renewed campaigns directed by Michael Rostovtzeff continued until 1937, when funds ran out with only part of the excavations published. World War II intervened. Since 1986 excavations have resumed in a joint Franco-Syrian effort under the direction of Pierre Leriche.

Not the least of the finds were astonishingly well-preserved arms and armour belonging to the Roman garrison at the time of the final Sassanian siege of 256 AD. Finds included painted wooden shields and complete horse armour, preserved by the very finality of the destruction of the city that journalists have called "the Pompeii of the desert". Finds from Dura-Europos are on display in the Deir ez-Zor Museum and the Yale University Art Gallery.[20]

Culture

Dura-Europos was a cosmopolitan society, controlled by a tolerant Macedonian aristocracy descended from the original settlers. In the course of its excavation, over a hundred parchment and papyrus fragments and many inscriptions have revealed texts in Greek and Latin (the latter including a sator square), Palmyrene, Hebrew, Hatrian, Safaitic, and Pahlavi. The excavations revealed temples to Greek, Roman and Palmyrene gods. There was a Mithraeum, as one would expect in a Roman military city.

The synagogue

The Jewish synagogue, located by the western wall between towers 18 and 19, the last phase of which was dated by an Aramaic inscription to 244. It is the best preserved of the many ancient synagogues of that era that have been uncovered by archaeologists. It was well preserved due to having been infilled with earth to strengthen the city's fortifications against a Sassanian assault in 256. It was uncovered in 1932 by Clark Hopkins, who found that it contains a forecourt and house of assembly with frescoed walls depicting people and animals, and a Torah shrine in the western wall facing Jerusalem. At first, it was mistaken for a Greek temple.

The synagogue paintings, the earliest continuous surviving biblical narrative cycle,[21] are conserved at Damascus, together with the complete Roman horse-armour.

The house church

There was also identified the Dura-Europos church, the earliest Christian house church, located by the 17th tower and preserved by the same defensive fill that saved the synagogue. "Their evidently open and tolerated presence in the middle of a major Roman garrison town reveals that the history of the early Church was not simply a story of pagan persecution".[22]

The building consists of a house conjoined to a separate hall-like room, which functioned as the meeting room for the church. The surviving frescoes of the baptistry room are probably the most ancient Christian paintings. We can see the "Good Shepherd" (this iconography had a very long history in the Classical world), the "Healing of the paralytic" and "Christ and Peter walking on the water". These are the earliest depictions of Jesus Christ ever found and date back to 235 AD.[23]

A much larger fresco depicts two women (and a third, mostly lost) approaching a large sarcophagus, i.e. probably the three Marys visiting Christ's tomb. There were also frescoes of Adam and Eve as well as David and Goliath. The frescoes clearly followed the Hellenistic Jewish iconographic tradition but they are more crudely done than the paintings of the nearby synagogue.

Fragments of parchment scrolls with Hebrew texts have also been unearthed; they resisted meaningful translation until J.L. Teicher pointed out that they were Christian Eucharistic prayers, so closely connected with the prayers in Didache that he was able to fill lacunae in the light of the Didache text.[24]

In 1933, among fragments of text recovered from the town dump outside the Palmyrene Gate, a fragmentary text was unearthed from an unknown Greek harmony of the gospel accounts — comparable to Tatian's Diatessaron, but independent of it.

The Mithraeum

Also partially preserved by the defensive embankment was the Mithraeum (CIMRM 34–70), located between towers 23 and 24. It was unearthed in January 1934 after years of expectation as to whether Dura would reveal traces of the Roman Mithras cult. The earliest archaeological traces found within the temple are from between AD 168 and 171,[25] which coincides with the arrival of Lucius Verus and his troops. At this stage it was still a room in a private home. It was extended and renovated between 209 and 211, and most of the frescoes are from this period. The tabula ansata of 210 offers salutation to Septimus Severus, Caracalla and Geta. The construction was managed by a centurio principe praepositus of the legio IIII Scythicae et XVI Flaviae firmae (CIMRM 53), and it seems that construction was done by imperial troops. The mithraeum was enlarged again in 240, but in 256—with war with Sassanians looming—the sanctuary was filled in and became part of the strengthened fortifications. Following excavations, the temple was transported in pieces to New Haven, Connecticut, where it was rebuilt (and is now on display) at the Yale University Art Gallery.

The surviving frescoes, graffiti and dipinti (which number in the dozens) are of enormous interest to the study of the social composition of the cult.[26] The statuary and altars were found intact, as also the typical relief of Mithras slaying the bull, with the hero-god dressed as usual in "oriental" costume ("trousers, boots, and pointed cap"). As is typical for mithraea in the Roman provinces in the Greek East, the inscriptions and graffiti are mostly in Greek, with the rest in Palmyrene (and some Hellenized Hebrew). The end of the sanctuary features an arch with a seated figure on each of the two supporting columns. Inside and following the form of the arch is a series of depictions of the zodiac.[27] Within the framework of the now-obsolete theory that the Roman cult was "a Roman form of Mazdaism" ("la forme romaine du mazdeisme"), Cumont supposed that the two Dura friezes represented the two primary figures of his Les Mages hellénisés, i.e. "Zoroaster" and "Ostanes".[28] This reading has not found a footing; "the two figures are Palmyrene in all their characteristic traits"[29] and are more probably portraits of leading members of that mithraeum's congregation of Syrian auxiliaries.[30]

International prize and UNESCO recognition

The Jury of the International Carlo Scarpa Prize for Gardens has unanimously decided that the twenty-first of these annual awards (2010) will go to Dura Europos.[31] In 1999 Dura Europos has been included in the possible "Tentative List" of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[32] Successively in 2011 has been included again, in the possible nominated list, with the nearby ancient city of Mari.

Current situation

In 2015, according to satellite imagery, more than 70% of Dura-Europos was destroyed by looters during the Syrian Civil War.[33]

National Geographic reported further plundering of the site on a massive scale by the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant terror group in order to fund their territorial hold on the region at the time.[34]

Popular culture

Fire in the East,[35] the first book in the Warrior of Rome series by the Oxford scholar Dr Harry Sidebottom, is centred around a detailed description of the Sassanid siege of Dura-Europos in 256 AD, based on the archeological finds in the site, although the city name has been changed to "Arete."

The Parthian,[36] is the first novel in the Parthian Chronicles series by Peter Darman. These chronicles are based around the fictional character Pacorus I, King of Dura-Europos (although the royal name Pacorus features prominently during the Parthian Empire) who lived at the same time as the rebel Roman gladiator Spartacus and was part of his army before being freed in Italy and then returns home to Parthia, where he becomes the most feared warrior in the empire.

See also

- Cohors XX Palmyrenorum, was an auxiliary cohort of the Roman Imperial army.

- Destruction of cultural heritage by ISIL

- Dura-Europos Route map, is the fragment of a speciality map discovered in 1923.

- Feriale Duranum, is a calendar on papyrus of religious observances for a Roman military garrison.

- List of cities of the ancient Near East

- Temple of Zeus Kyrios

- Temple of Adonis, Dura-Europos

- Temple of the Gadde

- Temple of Zeus Theos, Dura Europos

Notes

- Based on the chronology found in Hopkins, 1979, pp. 269–271.

- More recent analysis has brought into doubt this event. See, David McDonald, "Dating the Fall of Dura-Europos", Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, V.35/1 (1986), pp.45–68.

- McDonald, 1986, p.68, prefers 257 as the fall, based on the lateness in the year of the issue from the mint of the coins found at Dura which provided the year 256. He also argues that a garrison of Sassanid forces probably remained in the city for perhaps a year after the locals had been deported.

- "Ancient History, Modern Destruction: Assessing the seeStatus of Syria's Tentative World Heritage Sites Using High-Resolution Satellite Imagery". AAAS – The World's Largest General Scientific Society. 2014-12-16. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- Loot, sell, bulldoze: Isis grinds history to dust

- Pierre Leriche, D. N. MacKenzie, "Dura Europos", Encyclopaedia Iranica, December 15, 1996, last updated December 2, 2011.

- "History of Dura Europos". Archived from the original on 2009-01-23. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- Michael Ivanovitch Rostovtzeff. The Excavations at Dura-Europos, Volume 3, Part 1, Number 2 Yale University Press. p 288 (original from the University of Michigan)

- Harald Ingholt. Palmyrene and Gandharan Sculpture: An Exhibition Illustrating the Cultural Interrelations Between the Parthian Empire and Its Neighbors West and East, Palmyra and Gandhara, Oct. 14 Through Nov. 14, 1954 Yale University Art Gallery, 1954. p. 2

- Minna Lönnqvist. Jebel Bishri in Context: Introduction to the Archaeological Studies and the Neighbourhood of Jebel Bishri in Central Syria : Proceedings of a Nordic Research Training Seminar in Syria, May 2004 Archaeopress, 2008 ISBN 978-1407303031 p. 100 (original from the University of Michigan)

- Ross Burns (2009). Monuments of Syria: A Guide. I.B.Tauris. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-85771-489-3.

- F. Millar, "Dura-Europos under Parthian rule," in Das Partherreich und sein Zeugnisse/The Arsacid Empire: Sources and Documentation, J. Weisehöfer, ed. (Stuttgart) 1998

- F. Millar, The Roman Near east, 31 BC-AD337 (Harvard University Press) 1993, pp. 445–52, 467–72.

- Carly Silver: Dura Europos

- The description of the fall is heavily dependent on Clark Hopkins, "The Siege of Dura", The Classical Journal, 42/5 (1947), pp. 251–259.

- Buried Soldiers May Be Victims of Ancient Chemical Weapon, LiveScience

- Ancient Persians 'gassed Romans', BBC NEWS

- Earliest Chemical Warfare – Dura-Europos, Syria

- Ousterhout, Robert (2011). John Henry Haynes: A Photographer and Archaeologist in the Ottoman Empire 1881–1900. Istanbul: Kayık Yayıncılık. p. 41.

- Bonatz, Dominik; Kühne, Hartmut; Mahmoud, As'ad (1998). Rivers and steppes. Cultural heritage and environment of the Syrian Jezireh. Catalogue to the Museum of Deir ez-Zor. Damascus: Ministry of Culture. OCLC 638775287.

- Joseph Gutmann, "The Dura Europos Synagogue Paintings and Their Influence on Later Christian and Jewish Art" Artibus et Historiae 9'.17 (1988), pp. 25–29. Gutmann concluded that in their brief visible career the paintings had not had an appreeciable effect on later paintings.

- Simon James, from his webpage Archived 2009-01-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- McKay, John; Hill, Bennett (2011). A History of World Societies, Combined Volume (9 ed.). United States of America: Macmillan. p. 166. ISBN 9780312666910.

- J.L. Teicher, "Ancient Eucharistic Prayers in Hebrew (Dura-Europos Parchment D. Pg. 25)" The Jewish Quarterly Review New Series 54.2 (October 1963), pp. 99–109.

- Hopkins, p. 200

- cf. Francis 1975b, p. II.424f.

- Hopkins, p.201

- Cumont 1975, p. 184.

- Rostovtzeff, qtd. by

Francis 1975a, p. I.183, n. 174. - Francis 1975a, p. I.183, n. 174.

- "Fondazione Benetton Studi e Ricerche". Archived from the original on 2011-04-03. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- Dura Europos

- Amos, Deborah; Meuse, Alison (10 March 2015). "Via Satellite, Tracking The Plunder Of Middle East Cultural History". NPR. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- Sidebottom, Harry (September 6, 2017). Fire in the East. ASIN 0141032294.

- Darman, Peter (May 29, 2011). "The Parthian". Amazon.com. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

References

- Dirven, L.A. 1999 The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos : a study of religious interaction in Roman Syria (Leiden: Brill).

- Hopkins, C, 1979 The Discovery of Dura Europos, (New Haven and London).

- Rostovtzeff, M.I., 1938. Dura-Europos and Its Art (Oxford University Press).

- Cumont, Franz; Francis, Eric David, ed., trans. (1975), "The Dura Mithraeum", in Hinnells, John R. (ed.), Mithraic studies: Proceedings of the First International Congress of Mithraic Studies, Manchester UP, pp. I.151–214CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link).

- Francis, Eric David (1975b), "Mithraic graffiti from Dura-Europos", in Hinnells, John R. (ed.), Mithraic studies: Proceedings of the First International Congress of Mithraic Studies, Manchester UP, pp. II.424–445.

- Young, Penny, 2014 Dura Europos A City for Everyman, Twopenny Press

Further reading

- James, Simon (2011). "Stratagems, Combat, and "Chemical Warfare" in the Siege Mines of Dura-Europos". American Journal of Archaeology. 115 (1): 69–101. doi:10.3764/aja.115.1.69.

- James, Simon. 2019. The Roman Military Base at Dura-Europos, Syria: An Archaeological Visualization. Oxford University Press.

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed. (1979). Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century. Catalogue of the Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 19, 1977, Through February 12, 1978. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870991790.

- Dura Europos: Crossroads of Antiquity [Exh. Cat.], eds. Lisa R. Brody and Gail L. Hoffman. Chestnut Hill, MA: McMullen Museum of Art, with University of Chicago Press, 2011.

- Edge of Empires: Pagans, Jews, and Christians at Roman Dura-Europos [Exh. Cat.], eds. Jennifer Y. Chi and Sebastian Heath. NY: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University, and Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Baird, J. A. (2014). The Inner Lives of Ancient Houses: An Archaeology of Dura-Europos. Oxford: Oxford University Press.[1]

- Baird, J. A. (2018). Dura-Europos. Bloomsbury Archaeological Histories Series. London: Bloomsbury.[2]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dura Europos. |

- "Dura-Europos: Excavating Antiquity" at the Yale University Art Gallery

- Simon James, "Dura-Europos, the 'Pompeii of the Desert'"

- Illustration of the tomblike baptistry of the Christian church

- The Dura-Europos Gospel Harmony

- "7 vs. 8: The Battle Over the Holy Day at Dura-Europos"

- New York Times: "A Melting Pot at the Intersection of Empires for Five Centuries" By John Noble Wilford December 19, 2011

- Baird, J. A. (2014-08-28). The Inner Lives of Ancient Houses: An Archaeology of Dura-Europos. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199687657.

- Bloomsbury.com. "Dura-Europos". Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved 2019-06-28.