Caesarea

Caesarea (/ˌsɛzəˈriːə, ˌsɛsəˈriːə, ˌsiːzəˈriːə/) (Arabic: قيسارية, Hebrew: קֵיסָרְיָה), Keysariya or Qesarya, often simplified to Keisarya, and Qaysaria,[2] is a town in north-central Israel, which inherits its name and much of its territory from the ancient city of Caesarea Maritima (Greek: Καισάρεια[2]). Located midway between Tel Aviv and Haifa on the coastal plain near the city of Hadera, it falls under the jurisdiction of Hof HaCarmel Regional Council. With a population of 5,343,[1] it is the only Israeli locality managed by a private organization, the Caesarea Development Corporation,[3] and also one of the most populous localities not recognized as a local council.

Caesarea

קֵיסָרְיָה | |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • standard | Keisarya |

| • official | Qesarya |

Caesarea school | |

Caesarea  Caesarea | |

| Coordinates: 32°30′10″N 34°54′20″E | |

| Country | |

| District | Haifa |

| Council | Hof HaCarmel |

| Founded | 30 BCE (Herodian city) 1101 (Crusader castle) 1884 (Bosniak Ottoman village) 1952 (Israeli town) |

| Area | 35,000 dunams (35 km2 or 14 sq mi) |

| Population (2019)[1] | 5,343 |

| • Density | 150/km2 (400/sq mi) |

The ancient city of Caesarea Maritima was built by Herod the Great about 25–13 BCE as a major port. It served as an administrative center of the province of Judaea (later named Syria Palaestina) in the Roman Empire, and later as the capital of the Byzantine province of Palaestina Prima. During the Muslim conquest in the 7th century, it was the last city of the Holy Land to fall to the Arabs. The city degraded to a small village after the provincial capital was moved from here to Ramleh and had an Arab majority until Crusader conquest. Under the Crusaders it became once again a major port and a fortified city. It was diminished after the Mamluk conquest.[4] In 1884, Bosniak immigrants settled there establishing a small fishing village.[4] In 1940, kibbutz Sdot Yam was established next to the Bosniak village. In February 1948, the Bosniak village was conquered by a Palmach unit commanded by Yitzhak Rabin, its people already having fled following an earlier attack by the Lehi paramilitary group. In 1952, the modern Jewish town of Caesarea was established near the ruins of the old city, which in 2011 were incorporated into the newly created Caesarea National Park.

History

A historical overview is included in this article's introduction. For more about the Classical Era, Early Muslim, Crusader and Late Muslim periods before the resettlement in the 19th century, see here [→] in the history chapter of the Caesarea Maritima article.

Late Ottoman Qisarya (est. 1884)

Caesarea lay in ruins until the nineteenth century, when the village of Qisarya (Arabic: قيسارية) was established in 1884 by Bushnaks (Bosniaks) – immigrants from Bosnia, who built a small fishing village on the ruins of the fortified Crusader city.[5][6]

A population list from about 1887 showed that Caesarea had 670 Muslim inhabitants, in addition to 265 Muslim inhabitants, who were noted as "Bosniaks".[7]

Petersen, visiting the place in 1992, writes that the nineteenth-century houses were built in blocks, generally one story high (with the exception of the house of the governor.) Some houses on the western side of the village, near the sea, have survived. There were a number of mosques in the village in the nineteenth century, but only one ("The Bosnian mosque") has survived. This mosque, located at the southern end of the city, next to the harbour, is described as a simple stone building with a red-tiled roof and a cylindrical minaret. In 1992 it was used as a restaurant and as a gift shop.[8]

British Mandate of Palestine

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Caesarea had a population of 346; 288 Muslims, 32 Christians and 26 Jews,[9] where the Christians were 6 Orthodox, 3 Syrian Orthodox, 3 Roman Catholics, 4 Melkites, 2 Syrian Catholics and 14 Maronite.[10] The population had increased in the 1931 census to 706; 19 Christians, 4 Druse and 683 Muslims, in a total of 143 houses.[11]

A Jewish settlement, Kibbutz Sdot Yam, was established 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) south of the Muslim town in 1940.

The Muslim village declined in economic importance and many of Qisarya's Muslim inhabitants left in the mid-1940s, when the British extended the Palestine Railways which bypassed the shallow-draft port. Qisarya had a population of 960 in 1945 statistics,[12] with Qisarya's population composition 930 Muslims and 30 Christians in 1945.[13][12] In 1944/45 a total of 18 dunums of Muslim village land was used for citrus and bananas, 1,020 dunums were used for cereals, while 108 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards,[14][15] while 111 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[16]

Caesarea 1947

Caesarea 1947 Caesarea 1947

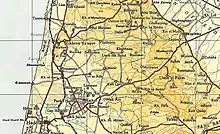

Caesarea 1947 Caesarea 1942 1:20,000

Caesarea 1942 1:20,000 Caesarea 1945 1:250,000

Caesarea 1945 1:250,000

1947–48 Civil War

The Civil War began on 30 November 1947. In December 1947 a village notable, Tawfiq Kadkuda, approached local Jews in an effort to establish a non-belligerency agreement.[17] The 31 January 1948 Lehi attack on a bus leaving Qisarya, which killed two and injured six people, precipitated an evacuation of most of the population, who fled to nearby al-Tantura.[18] The Haganah then occupied the village because the land was owned by the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association and, fearing that the British would force them to leave, decided to demolish the houses.[18] This was done on 19–20 February, after the remaining residents were expelled and the houses were looted.[18] According to Benny Morris, the expulsion of the population had more to do with illegal Jewish immigration than the ongoing civil war.[19] In the same month the 'Arab al Sufsafi and Saidun Bedouin, who inhabited the dunes between Qisarya and Pardes left the area.[20]

Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi described the village remains in 1992: "Most of the houses have been demolished. The site has been excavated in recent years, largely by Italian, American, and Israeli teams, and turned into a tourist area. Most of the few remaining houses are now restaurants, and the village mosque has been converted into a bar."[21]

State of Israel

Rothschild Caesarea Foundation and Development Corporation

After the establishment of the State of Israel, the Rothschild family agreed to transfer most of its land holdings to the new state. A different arrangement was reached for the 35,000 dunams of land the family owned in and around modern Caesarea: after turning over the land to the state, it was leased back (for a period of 200 years) to a new charitable foundation. In his will, Edmond James de Rothschild stipulated that this foundation would further education, arts and culture, and welfare in Israel. The Caesarea Edmond Benjamin de Rothschild Foundation was formed and run based on the funds generated by the sale of Caesarea land which the Foundation is responsible for maintaining. The Foundation is owned half by the Rothschild family, and half by the State of Israel.

The Rothschild Caesarea Foundation established the Caesarea Edmond Benjamin de Rothschild Development Corporation Ltd. (CDC; Hebrew: החברה לפיתוח קיסריה אדמונד בנימין דה רוטשילד) in 1952 to act as its operations arm. The company transfers all profits from the development of Caesarea to the Foundation, which in turn contributes to organizations that advance higher education and culture across Israel. The goal of the CDC is to establish a unique community that combines quality of life and safeguarding the environment with advanced industry and tourism.

Today, the Chairman of the Rothschild Caesarea Foundation and the CDC is Baron Benjamin de Rothschild, the great-grandson of Baron Edmond de Rothschild.

As well as carrying out municipal services, the CDC markets plots for real-estate development, manages the nearby industrial park, and runs the Caesarea's golf course and country club, Israel's only 18-hole golf course.

Kesariya's character

Modern Caesarea, or Kesariya, remains today the only locality in Israel managed by a private organization rather than a municipal government. It is one of Israel's most upscale residential communities. The Baron de Rothschild still maintains a home in Caesarea, as do many business tycoons from Israel and abroad.

Location and structure of modern Keisariya

Modern Keisariya, located adjacent to ancient Caesarea, is located on the Israeli coastal plain, approximately halfway between the major modern cities of Tel Aviv (45 kilometers (28 mi) to the south) and Haifa (45 kilometers (28 mi) to the north). Caesarea is situated approximately 5 kilometers (3 mi) northwest of the city of Hadera, and is bordered to the east by the Caesarea Industrial Zone and the city of Or Akiva. Directly to the north of Caesarea is the town of Jisr az-Zarqa.

Keisariya is divided into a number of residential zones, known as clusters. The most recent of these to be constructed is Cluster 13, which, like all the clusters, is given a name: in this case, "The Golf Cluster", due to its close proximity to the Caesarea Golf Course. The golfcourse was built upon an ancient Arab town on the site of a loosely grouped Egyptian and subsequently Greek structures, with archaeological remains. These neighborhoods are affluent, although they vary significantly in terms of average plot size.

Economy

Caesarea is a suburban community with a number of residents commuting to work in Tel Aviv or Haifa.

The Caesarea Business Park is on the fringe of the city. About 170 companies are in the park; they employ about 5,500 people. Industry in the park includes distribution and high-technology services.

The residential neighborhoods have a shopping concourse with a newsagent, supermarket, optician, and bank. A number of restaurants and cafes are scattered across the town, with a number within the ancient port.

Infrastructure

Roads

Beyond the eastern boundary of the residential area of Caesarea is Highway 2, Israel's main highway linking Tel Aviv to Haifa. Caesarea is linked to the road by the Caesarea Interchange in the south, and Or Akiva Interchange in the center.

Beyond the eastern boundary of the residential area of Caesarea is Highway 2, Israel's main highway linking Tel Aviv to Haifa. Caesarea is linked to the road by the Caesarea Interchange in the south, and Or Akiva Interchange in the center. Slightly further to the east lies Highway 4, providing more local links to Hadera, Binyamina, Zichron Yaakov, and the moshavim and kibbutzim of Emek Hefer.

Slightly further to the east lies Highway 4, providing more local links to Hadera, Binyamina, Zichron Yaakov, and the moshavim and kibbutzim of Emek Hefer. Highway 65 starts at the Caesarea Interchange and runs westwards into the Galilee and the cities of Pardes Hanna-Karkur, Umm al-Fahm, and Afula.

Highway 65 starts at the Caesarea Interchange and runs westwards into the Galilee and the cities of Pardes Hanna-Karkur, Umm al-Fahm, and Afula.

Rail

Caesarea shares a railway station with nearby Pardes Hanna-Karkur, which is situated in the Caesarea Industrial Zone and is served by the suburban line between Binyamina and Tel Aviv, with two trains per hour. The Binyamina Railway Station, a major regional transfer station, is also located nearby.

Culture

The Roman theatre, located at the site, often hosts concerts by major Israeli and international artists, such as Shlomo Artzi, Yehudit Ravitz, Mashina, Deep Purple, Björk, and others. In recent years, the port has become home to the annual Caesarea Jazz Festival, which offers three evenings of top-class jazz performances by leading international artists. The Ralli Museum in Caesarea houses a large collection of South American art and several Salvador Dalí originals.[22]

Sports

Caesarea has the country's only full-sized golf course.[23] The idea for the Caesarea Golf and Country Club originated after James de Rothschild was reminded by the dunes surrounding Caesarea of Scotland's sandy links golf courses. Upon his death, the James de Rothschild Foundation established the course. In 1958, a Golf Club Committee was established, and a course was built. American professional golfer Herman Barron, the first Jewish golfer to win a PGA Tour event, helped develop the course.[24] It was officially opened in 1961 by Abba Eban. The Caesarea Golf Club has hosted international golf competitions every four years in the Maccabiah Games. The course was redesigned and rebuilt by golf course designer Pete Dye in 2007–2009.[25]

Notable residents

- Saint Albina

- Keren Ann (born 1974), pop singer-songwriter

- Laetitia Beck (born 1992), Belgian-born Israeli LPGA golfer

- Noga Erez (born 1989), singer

- Amit Farkash (born 1989), Canadian-born Israeli actress and singer

- Arcadi Gaydamak (born 1952), Russian-Israeli businessman

- Benjamin Netanyahu (born 1949), politician and the current Prime Minister of Israel

- Avraham Yosef Schapira (1921-2000), politician and a businessman

- Dan Shilon (born 1940), television host, director, and producer

- Ezer Weizman (1924–2005), seventh President of Israel

- Eitan Wertheimer (born 1926), industrialist and politician

References

- "Population in the Localities 2019" (XLS). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Caesarea" in the American Heritage Dictionary

- About the CDC Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Caesarea". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- Oliphant, 1887, p. 182

- "Caesarea". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- Schumacher, 1888, p. 181

- Petersen, 2001, pp. 129-130

- Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Haifa, p. 34

- Barron, 1923, Table XVI, p. 49

- Mills, 1932, p. 95

- Department of Statistics, 1945, p.14

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 49

- Khalidi, 1992, p. 183

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 91

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 141

- Morris, 2004, p. 92

- Morris, 2004, p. 130

- Morris, 2008, pp. 94–95.

- Morris, 2004, p. 129

- Khalidi, 1992, p.184

- "Caesarea". Weizmann Institute. Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2008.

- Golf Digest magazine, May 2010

- Herman Barron bio page on International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame website

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Country Club – About

Bibliography

- Abu Shama (d. 1268) (1969): Livre des deux jardins ("The Book of Two Gardens"). Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Cited in Petersen (2001).

- Al-Baladhuri (1916). The origins of the Islamic state: being a translation from the Arabic, accompanied with annotations, geographic and historic notes of the Kitâb fitûh al-buldân of al-Imâm abu-l Abbâs Ahmad ibn-Jâbir al-Balâdhuri. Translator: Philip Khuri Hitti. New York: Columbia University.

- Ad, Uzi (9 May 2007). "Caesarea, The High Aqueduct in Nahal 'Ada" (119). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Avner, Rita; Gendelman, Peter (30 January 2007). "Caesarea" (119). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Barber, Richard W. (2004). The Holy Grail: imagination and belief. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674013905.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (pp. 12-29, 34)

- Crossan, J.D. (1999). Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Christ. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-567-08668-2.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Gendelman, Peter (24 July 2011). "Caesarea" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gendelman, Peter; Massarwa, Abdallah (15 August 2011). "Caesarea, Sand Dunes (South)" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Guérin, V. (1875). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 2: Samarie, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Levine, Lee I (1975). Caesarea under Roman rule. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-04013-7.

- Mariti, Giovanni (1792). Travels Through Cyprus, Syria, and Palestine; with a General History of the Levant. 1. Dublin: P. Byrne. (p. 396 ff)

- Meyers, E.M. (1999). ""The Fall of Caesarea Maritima"". Galilee Through the Centuries. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 157506040X.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Morris, B. (2008). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12696-9.

- Oliphant, L. (1887). Haifa, or Life in Modern Palestine. archive.org.

- Oren, Eliran (1 June 2010). "Caesarea" (122). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Porat, Yosef (31 May 2004). "Caesarea" (116). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pringle, Denys (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A-K (excluding Acre and Jerusalem). I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 39036 2.

- Pringle, Denys (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetter. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521 46010 7.

- Ringel, Joseph (1975). Césarée de Palestine: étude historique et archéologique (in French). Éditions Ophrys, University of California.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. (p. 44)

- Safrai, Z. (1994). The Economy of Roman Palestine. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10243-X.

- Sa‘id, Kareem (22 May 2006). "Caesarea" (116). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sa‘id, Kareem (10 July 2007). "Caesarea" (119). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Seetzen, U.J. (1854). Ulrich Jasper Seetzen's Reisen durch Syrien, Palästina, Phönicien, die Transjordan-länder, Arabia Petraea und Unter-Aegypten (in German). 2. Berlin: G. Reimer.

- Sharon, M. (1999). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, B–C. 2. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-11083-6.(Sharon, 1999, pp. 252)

- al-'Ulaymi Sauvaire (editor) (1876): Histoire de Jérusalem et d'Hébron depuis Abraham jusqu'à la fin du XVe siècle de J.-C. : fragments de la Chronique de Moudjir-ed-dyn p. 80–81

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caesarea. |

- Places To Visit in Caesarea (English)

- Welcome To Qisarya

- Qisarya, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine Map 7: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Caesarea Development Corporation

- Jacques Neguer, Byzantine villa:Conservation of the "gold table" and preparation for its display, Israel Antiquities Authority Site - Conservation Department

.jpg.webp)