Dutch pacification campaign on Formosa

The Dutch Pacification Campaign on Formosa was a series of military actions and diplomatic moves undertaken in 1635 and 1636 by Dutch colonial authorities in Dutch-era Taiwan (Formosa) aimed at subduing hostile aboriginal villages in the southwestern region of the island. Prior to the campaign the Dutch had been in Formosa for eleven years, but did not control much of the island beyond their principal fortress at Tayouan, and an alliance with the town of Sinkan. The other aboriginal villages in the area conducted numerous attacks on the Dutch and their allies, with the chief belligerents being the village of Mattau, who in 1629 ambushed and slaughtered a group of sixty Dutch soldiers.

| Dutch pacification campaign on Formosa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Natives of Mattau, Bakloan, Soulang, Taccariang and Tevorang | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

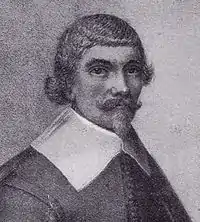

| Hans Putmans | unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 500 Dutch soldiers | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| exact numbers unknown, casualties slight |

c. 30 killed Mattau and Taccariang destroyed by fire | ||||||

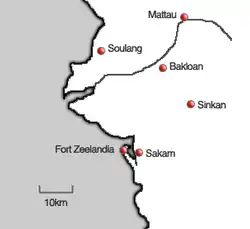

Location of Mattau, the most important target of the campaign | |||||||

After receiving reinforcements from the colonial headquarters at Batavia, the Dutch launched an attack in 1635 and were able to crush opposition and bring the area around present-day Tainan fully under their control. After seeing Mattau and Soulang, the most powerful villages in the area, defeated so comprehensively, many other villages in the surrounding area came to the Dutch to seek peace and surrender sovereignty. Thus the Dutch were able to dramatically expand the extent of their territorial control in a short time, and avoid the need for further fighting. The campaign ended in February 1636, when representatives from twenty-eight villages attended a ceremony in Tayouan to cement Dutch sovereignty.

Solidifying the southwest under their rule, the Dutch were able to expand their operations from the limited entrepôt trading carried out by the colony prior to 1635. The expanded territory allowed access to the deer trade, which later became very lucrative, and guaranteed security in food supplies. It provided fertile land, which the Dutch used imported Chinese labour to farm. The aboriginal villages also provided warriors to aid the Dutch in times of trouble, notably in the Lamey Island Massacre of 1636, the Dutch defeat of the Spanish in 1642 and the Guo Huaiyi Rebellion in 1652. The allied villages also provided opportunities for Dutch missionaries to spread their faith. The pacification campaign is considered the foundation stone on which the later success of the colony was built.

Background

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) arrived in southern Formosa in 1624 and, after building their stronghold of Fort Zeelandia on the peninsula of Tayouan, began to sound out local villages as to the possibility of forming alliances. Although initially the intention was to run the colony solely as an entrepôt (a trading port), the Dutch later decided that they needed control over the hinterland to provide some security.[1] Additionally, a large percentage of supplies for the Dutch colonists had to be shipped from Batavia at great expense and irregular intervals, and the government of the fledgling colony was keen to source foodstuffs and other supplies locally.[2] The Company decided to ally with the closest village, the relatively small Sinkan, who were able to supply them firewood, venison and fish.[3] However, relations with the other villages were not so friendly. The aboriginal settlements of the area were involved in more or less constant low-level warfare with each other (head-hunting raids and looting of property),[4] and an alliance with Sinkan put the Dutch at odds with the foes of that village. In 1625 the Dutch bought a piece of land from the Sinkaners for the sum of fifteen cangans (a kind of cloth), where they then built the town of Sakam for Dutch and Chinese merchants.[5]

Initially other villages in the area, chiefly Mattau, Soulang and Bakloan, also professed their desire to live in peace with the Dutch.[6] The villages saw that it was in their interest to maintain good relations with the newcomers, but this belief was weakened by a series of incidents between 1625 and 1629. The earliest of these was a Dutch attack on Chinese pirates in the bay of Wancan, not far from Mattau, in 1625. The pirates were able to drive off the Dutch soldiers, causing the Dutch to lose face among the Formosan villages.[7] Encouraged by this Dutch failure, warriors from Mattau raided Sinkan, believing the Dutch too weak to defend their Formosan friends. At this point, the Dutch returned to Wancan and this time were able to rout the pirates, restoring their reputation.[8] Mattau was then forced by the colonials to return the property stolen from Sinkan and make reparations in the form of two pigs.[8] The peace was short-lived, however, because in November 1626 the villagers of Sinkan attacked Mattau and Bakloan, before going to the Dutch to ask for protection from retribution.[9] Although the Dutch were able to force Sinkan's enemies to back down in this case, in later incidents they proved incapable of fully protecting their Formosan allies.[9]

Frustrated by the inability of the Dutch to protect them, the Sinkan villagers turned to Japanese traders, who were not on friendly terms with the VOC. In 1627 a delegation from the village visited Japan in order to ask for Japanese protection and to offer sovereignty to the Japanese Shōgun Tokugawa Iemitsu.[10] The Shōgun refused them an audience, but on their return to Formosa the Sinkan villagers, along with their erstwhile foes from Mattau, Bakloan and Soulang, went to Governor Nuyts to demand that the company pay an annual tribute to the villages for operating on their land. The Governor refused.[11] Soon after, the Japanese isolationist policy of sakoku removed Japanese support for the Formosans, leaving Sinkan once more at the mercy of its rivals, prompting missionary George Candidius to write that "this village Sinkan has been until now under Dutch protection, and without this protection it would not stand for even a month."[12] In 1629 however the Dutch were unable to defend either themselves or their allies. Governor Nuyts went to Mattau on an official (friendly) visit with a guard of sixty musketeers, who were fêted on their arrival. After leaving the village the next morning, the musketeers were ambushed while crossing a stream and slaughtered to a man, by warriors of both Mattau and Soulang. The Governor had a lucky escape as he had returned to Fort Zeelandia the previous evening.[13]

Shortly after the massacre Governor Nuyts was recalled by the VOC governor-general in Batavia for various offences, including responsibility for the souring of relations with the Japanese. Hans Putmans replaced Nuyts as governor,[14] and immediately wanted to attack the ringleaders in Mattau, but the village was judged too strong to assault directly. Therefore, the Dutch moved against the weaker Bakloan, who they believed sheltered proponents of the massacre, setting out on 23 November 1629, and returning later that day "having killed many people and burned most of the village."[15] The Bakloan villagers sued for peace, and Mattau too signed a nine-month peace accord with the company.[16] However, in the years that followed, the Mattau, Bakloan and Soulang villagers continued a concerted campaign to harass employees of the company, particularly those who were rebuilding structures destroyed by the Mattauers in Sakam.[16] The situation showed no signs of improvement for the Dutch, until relations between Mattau and Soulang soured in late 1633 and early 1634. The two villages went to war in May 1634, and although Mattau won the fight, the company was happy to see divisions among the villages which it felt it could exploit.[17]

Dutch retaliation

Although both Governor Nuyts and subsequently Governor Putmans wanted to move against Mattau, the garrison at Fort Zeelandia numbered only 400, of which 210 were soldiers – not enough to undertake a major campaign without leaving the Dutch fortress guard under-strength.[18] After persistent unheeded requests from the two governors, in 1635 Batavia finally sent a force of 475 soldiers to Taiwan, to "avenge the murder of the expeditionary force against Mattau in 1629, to increase the prestige of the Company, and to obtain the respect and authority, necessary for the protection of the Chinese who had come all the way from China, to cultivate the land."[19]

By this stage, relations with the other villages had also deteriorated to the extent that even Sinkan, previously thought to be tightly bound to the Dutch, was plotting rebellion. The missionary Robert Junius, who lived among the natives, wrote that "rebels in Sinkan have conspired against our state . . . and [are planning] to murder and beat to death the missionaries and soldiers in Sinkan."[20] The governor in Tayouan moved quickly to quell the uprising, sending eighty soldiers to the village and arresting some of the key conspirators.[21] With potential disaster averted in Sinkan, the Dutch were further encouraged by the news that Mattau and Soulang, their principal enemies, were being ravaged by smallpox, whereas Sinkan, now back under Dutch control, was spared the disease – this being viewed as a divine sign that the Dutch were righteous.[22]

On 22 November 1635, the newly arrived forces set out for Bakloan, headed by Governor Putmans. Junius joined him with a group of native warriors from Sinkan, who had been persuaded to take part by the clergyman in order to further good relations between themselves and the VOC.[23] The plan was initially to rest there for the night, before attacking Mattau the next morning, but the Dutch forces received word that the Mattau villagers had learned of their approach and planned to flee.[23] They therefore decided to press on and attack that evening, succeeding in surprising the Mattau warriors and subduing the village without a fight.[24] The Dutch summarily executed 26 men of the village, before setting fire to the houses and returning to Bakloan.[24]

- That all the relics which they still possessed, be it of beads or garments should be restored to us.

- That they were to pay a certain contribution in pigs and paddy.

- That every second year they should bring two pigs to the Castle on the anniversary day of the murder.

- That they should give us the sovereignty over their country, and as a symbol thereof place at the feet of the Governor some little pinang and cocoa trees, planted in the earthen vessels in the soil of their country.

- That they should promise never again to turn their arms against us.

- That they should no longer molest the Chinese.

- That, in case we had to wage war against other villages, they should join us.

On the way back to Fort Zeelandia, the troops stopped in Bakloan, Sinkan and Sakam, at each step warning the chiefs of the village of the price of angering the VOC, and obtaining guarantees of friendly conduct in the future.[24] The village of Soulang sent two representatives to the Dutch while they were resting in Sinkan, offering a spear and a hatchet as a symbol that they would ally their forces to the Dutch.[24] Also present with offers of friendship were men from Tevorang (modern-day Yujing District), a collection of three villages in the hills previously outside Dutch influence.[24] Finally two chiefs from Mattau arrived, kow-towing to the Dutch officials and wishing to sue for peace.[26]

The aborigines signalled their surrender by sending a few of their best weapons to the Dutch, and then by bringing a small tree (often betel nut) planted in earth from their village as a token of the granting of sovereignty to the VOC.[27] Over the next few months as word of the Dutch victory spread, more and more villages came to pay their respects at Fort Zeelandia and assure the VOC of their friendly intentions.[28] However, the new masters of Mattau also inherited their enemies, with both Favorlang and Tirosen expressing hostility towards the VOC in the wake of their victory.[29]

After the victory over Mattau the governor decided to make use of the soldiers to cow other recalcitrant villages, starting with Taccariang, who had previously killed both VOC employees and Sinkan villagers. The villagers first fought with the Sinkanders who were acting as a vanguard, but on receiving a volley from the Dutch musketeers the Taccariang warriors turned and fled. The VOC forces entered the village unopposed, and burnt it to the ground.[30] From Taccariang they moved on to Soulang, where they arrested warriors who had participated in the 1629 massacre of sixty Dutch soldiers and torched their houses.[31] The last stop on the campaign trail was Tevorang, which had previously sheltered wanted men from other villages. This time the governor decided to use diplomacy, offering gifts and assurances of friendship, with the consequences of resistance left implicit. The Tevorangans took the hint, and offered no opposition to Dutch rule.[31]

Pax Hollandica

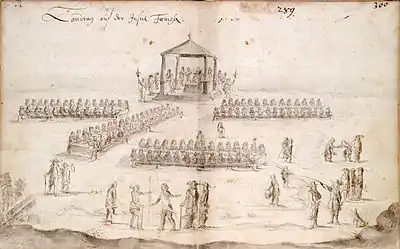

On hearing of the Dutch show of force, aboriginal tribes from further afield decided to submit to Dutch rule, either through fear of Dutch military might or hope that such an alliance would prove beneficial to the tribe. Representatives came from Pangsoia (Pangsoya; modern-day Linbian, Pingtung), 100 km to the south, to ally themselves with the VOC.[32][33] The Dutch decided to hold a landdag (a grand convention) to welcome all the villages into the fold and impress them with Dutch largesse and power. This duly took place on 22 February 1636, with 28 villages represented from southern and central Formosa.[34] The governor presented the attendees with robes and staffs of state to symbolise their position, and Robert Junius wrote that "it was delightful to see the friendliness of these people when they met for the first time, to notice how they kissed each other and gazed at one another. Such a thing had never before been witnessed in this country, as one tribe was nearly always waging war against another."[35]

The net effect of the Dutch campaign was a pax Hollandica (Dutch peace), assuring VOC control in the southwest of the island.[36] The Dutch called their new area of control the Verenigde Dorpen (United Villages), a deliberate allusion to the United Provinces of their homeland.[37] The campaign was vital to the success and growth of the Dutch colony, which had operated as more of a trading post than a true colony until that point.[37]

Other pacification campaigns

Earlier

In 1629, the third governor of Dutch Formosa, Pieter Nuyts, dispatched 63 Dutch soldiers to Mattau with the excuse of "arresting Chinese pirates". The effort was impeded by the local indigenous Taivoan people, as they had been resentful at the Dutch colonists who invaded and slaughtered many of their people. On the way back, the 63 Dutch soldiers were drowned by the indigenous people of Mattau, resulting in the retaliation of Pieter Nuyts and later the Mattau Incident (麻豆社事件) in 1635.[38]

On November 23, 1635, Nuyts led 500 Dutch soldiers and 500 Siraya soldiers from Sinckan to assail Mattau, killing 26 tribal people and burning all the buildings in Mattau. On December 18, Mattau surrendered and signed the Mattau Act (麻豆條約) with the Dutch governor. In this act, Mattau agreed to grant all the land inherited or controlled and all the properties owned by the people of Mattau to the Dutch. The Mattau Act has two significant meanings in the history of Taiwan:[39]

Later

Multiple Aboriginal villages rebelled against the Dutch in the 1650s due to oppression like when the Dutch ordered aboriginal women for sex, deer pelts, and rice be given to them from aborigines in the Taipei basin in Wu-lao-wan village which sparked a rebellion in December 1652 at the same time as the Chinese rebellion. Two Dutch translators were beheaded by the Wu-lao-wan aborigines and in a subsequent fight 30 aboriginals and another two Dutch people died, after an embargo of salt and iron on Wu-lao-wan the aboriginals were forced to sue for peace in February 1653.[40]

Notes

- Shepherd (1993), p. 49.

- van Veen (2003), p. 143.

- van Veen (2003), p. 142.

- Chiu (2008), p. 24.

- Shepherd (1993), p. 37.

- "Around Tayouan lie various villages. The inhabitants of these come daily to our fort, each trying to be the first to gain our friendship." Quoted in Andrade (2005), §1

- Andrade (2005), §4.

- Andrade (2005), §5.

- Andrade (2005), §6.

- Blussé (2003), p. 103.

- Andrade (2005), §8.

- Quoted in Andrade (2005), §9

- Andrade (2005), §10.

- Junius (1903), p. 116.

- Quoted in Andrade (2005), §11

- Andrade (2005), §11.

- Andrade (2005), §16.

- van Veen (2003), p. 148.

- Quoted in van Veen (2003), p. 149

- Quoted in Andrade (2005), §22

- Andrade (2005), §23.

- Andrade (2005), §24.

- Junius (1903), p. 117.

- Junius (1903), p. 118.

- Junius (1903), pp. 119–20.

- Junius (1903), p. 119.

- Covell (1998), p. 83.

- Andrade (2005), §26.

- Andrade (2005), §27.

- Andrade (2005), §28.

- Andrade (2005), §29.

- Andrade (2005), §30.

- Chiu (2008), pp. xviii–xix.

- Andrade (2005), §31.

- Quoted in Andrade (2005), §32

- Andrade (2005), §33.

- Andrade (2005), §2.

- Wong, Jiayin (2011-09-24). "麻豆社事件 (Mattau Incident)". 台灣故事館. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- "麻豆協約◎福爾摩沙第一份簽署的主權讓渡和約 (Mattau Act, the First Sovereignty Grant Act Signed in Formosa)". E大調. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- Shepherd1993, p. 59.

References

- Andrade, Tonio (2005). "Chapter 3: Pax Hollandica". How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century. Columbia University Press.

- Blussé, Leonard (2003). "Bull in a China Shop: Pieter Nuyts in China and Japan (1627–1636)". In Blussé (ed.). Around and About Dutch Formosa. Taipei: Southern Materials Center. ISBN 9789867602008.

- Chiu, Hsin-hui (2008). The Colonial 'Civilizing Process' in Dutch Formosa 1624–1662. ISBN 9789047442974.

- Covell, Ralph R. (1998). Pentecost of the Hills in Taiwan: The Christian Faith Among the Original Inhabitants (illustrated ed.). Hope Publishing House. ISBN 9780932727909. OCLC 833099470.

- Junius, R. (1903) [1636]. "Robertus Junius to the Directors of the Amsterdam Chamber of Commerce of the East India Company". In Campbell, William (ed.). Formosa under the Dutch: Described from Contemporary Records. London: Kegan Paul. OCLC 644323041.

- Shepherd, John (1993). Statecraft and Political Economy on the Taiwan Frontier, 1600–1800. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804720663.

- van Veen, Ernst (2003). "How the Dutch Ran a Seventeenth-Century Colony: The Occupation and Loss of Formosa 1624–1662". In Blussé, Leonard (ed.). Around and About Formosa. Taipei: Southern Materials Center. ISBN 9789867602008. OL 14547859M.