Taivoan people

The Taivoan (![]() pronunciation; 大滿族) or Tevorangh (

pronunciation; 大滿族) or Tevorangh (![]() pronunciation; 大武壠族) people or Shisha (四社; 'Four tribes'), also written Taivuan and Tevorang, Tivorang, Tivorangh, are an indigenous people in Taiwan. The Taivoan originally settled around hill and basin areas in Tainan, especially in the Yujing Basin, which area the Taivoan called Tamani, later transliterated into Japanese Tamai (玉井) and later borrowed as Chinese Yujing. The Taivoan historically called themselves Taivoan, Taibowan, Taiburan or Shisha as endonyms.[1][2]

pronunciation; 大武壠族) people or Shisha (四社; 'Four tribes'), also written Taivuan and Tevorang, Tivorang, Tivorangh, are an indigenous people in Taiwan. The Taivoan originally settled around hill and basin areas in Tainan, especially in the Yujing Basin, which area the Taivoan called Tamani, later transliterated into Japanese Tamai (玉井) and later borrowed as Chinese Yujing. The Taivoan historically called themselves Taivoan, Taibowan, Taiburan or Shisha as endonyms.[1][2]

Taivoan, Taibowan, Taiburan, Shisha | |

|---|---|

Taivoan elders in traditional dress at the Night Ceremony in Xiaolin, Kaohsiung. | |

| Total population | |

| More than 20,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Kaohsiung, Tainan, Taitung and Hualien in Taiwan | |

| Languages | |

| Taivoan, Taiwanese, Mandarin | |

| Religion | |

| Animism, Taoism, Buddhism, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Siraya, Makatao, Taiwanese indigenous peoples |

| Taiwanese indigenous peoples |

|---|

|

| Peoples |

|

Nationally Recognized Locally recognized Unrecognized |

| Related topics |

According to some scholars, there should be more than 20,000 Taivoan people nowadays, estimated based on the records during Japanese rule of Taiwan, ranked as the second largest non-status indigenous people in Taiwan, only second to Makatao people.[3]

Many scholars propose that the name of the island Taiwan actually came from the indigenous people's name, as the pronunciation of Taivoan is similar to Tayovan, the people that the Dutch met around the coast of Anping or the bay around Anping, which later became the name Taiwan. Also the Taivoan established a settlement called Taiouwang, which is the only indigenous community that sounds like Taiwan.[4][5]

History

The Taivoan people are ethnically called "Taivoan" or "Tevorangh". While the former term comes from the self-identification of the indigenous people recorded by Japanese linguists in the early 20th century, the latter comes from one of the four main tribes or nations established by the Taivoan in the early 17th century, well-recorded by the Dutch and Chinese people in a couple of documents, in different spellings including Tevorang, Tevoran, Tefurang, Devoran, Tivorang, Tivorangh, and the like.[4][6] Farrell also noted that the two terms "Tevorangh and Taivoan are probably dialectal variants of a common name (< *tayvura-n)".[7]

In December 1628, George Candidius, the first missionary to Dutch Formosa, wrote that there were eight tribes around modern-day Tainan, including "Sinkan, Mattau, Soulang, Bakloan, Taffakan, Tifulukan, Teopan and Tefurang", among which "the most remote village is Tefurang, which lies between the mountains".[6] In 1694, Chinese officer Kao Gong-qian (高拱亁) recorded the first Chinese record of Tevorangh in "Taiwan Prefecture Gazetteer" (臺灣府志), stating that the tribe was located to the northwest of Ma-an Mt.[8] Both records show the tribes' location and living environment in mountainous area of Taivoan or Tevorangh, compared to the Siraya and Makatao – the two indigenous peoples with a close relationship to Taivoan – who inhabit the lowland only.[4][9]

Mattau Incident

In 1629, the third governor of Dutch Formosa, Pieter Nuyts, dispatched 63 Dutch soldiers to Mattau with the excuse of "arresting Chinese pirates". The effort was impeded by the local indigenous people, as they had been resentful at the Dutch colonists who invaded and slaughtered many of their people. On the way back, the 63 Dutch soldiers were drowned by the indigenous people of Mattau, resulting in the retaliation of Pieter Nuyts and later the Mattau Incident (麻豆社事件) in 1635.[10]

On November 23, 1635, Nuyts led 500 Dutch soldiers and 500 Siraya soldiers from Sinckan to assail Mattau, killing 26 tribal people and burning all the buildings in Mattau. On December 18, Mattau surrendered and signed the Mattau Act (麻豆條約) with the Dutch governor Hans Putmans. In this act, Mattau agreed to grant all the land inherited or controlled and all the properties owned by the people of Mattau to the Dutch. The Mattau Act has two significant meanings in the history of Taiwan:[11]

- The Mattau Act is the first sovereignty grant act signed between Taiwanese indigenous people and a foreign sovereignty in the history.

- The sovereignty of the Formosans or the Taiwanese indigenous peoples was recognized by the Dutch government.

Resistance against Japanese

As a resistance to the long-term oppression by the Japanese government, many Taivoan people from Jiasian led the first local rebellion against Japan in July 1915, called the Jiasian Incident (甲仙埔事件). This was followed by a wider rebellion from Yuchin Basin in Tainan to Jiasian in Kaohsiung in August 1915, known as the Tapani Incident (噍吧哖事件) in which more than 1,400 local people died or were killed by the Japanese government. Twenty-two years later, the Taivoan people struggled to carry on another rebellion; since most of the indigenous people were from Xiaolin, the resistance taking place in 1937 was named the Xiaolin Incident (小林事件).[5]

Classification and self-identification

The Taivoan people used to be classified as a subgroup of Siraya; however, Raleigh Farrell regards Taivoan as an indigenous ethnic group according to 17th century documents, and believes there were at least five indigenous peoples in the south-western plain of Taiwan at that time:[7]

- Siraya

- Tevorang-Taivuan

- Takaraian (now classified as Makatao)

- Pangsoia-Dolatok (now classified as Makatao)

- Longkiau (now classified as Paiwan)

That Tevorang is sometimes considered to be a Siraya village is mainly based on George Candidius' inclusion "Tefurang" in the eight Siraya villages that he claimed all had "the same manners, customs and religion, and speak the same language". Ferrell mentioned that this is erroneous and that Candidious' assertion that he was well familiar with the eight supposed Siraya villages including Tevorang is extremely doubtful, as "he had not visited Tevorang when he wrote his famous account in 1628. The first Dutch visit to Tevorang appears to have been in January 1636".[7]

Japanese anthropologist Toichi Mabuchi and many modern scholars including Shigeru Tsuchida, Li, Paul Jen-kuei, Liu, I-chang, Chien, Wen-ming, Hu, Chia-yu, Lin, Ging-cai, and Zhang, Yao-qi also regard Taivoan as an independent Taiwanese indigenous people from the aspects of linguistics and anthropology.[1][12][13][4][9][14]

On October 6, 2016, Taivoan people across Kaohsiung held the first Inter-tribal Consensus Conference of Taivoan People and made a consensus statement that both "Tevorangh" (the classification recorded since the 17th century) and "Taivoan" (the classification since the 20th century) are accepted by the Taivoan people, but they refuse to be identified as "Siraya" or a subgroup of the Siraya people.[3]

Distribution

According to the oral history, Taivoan people originally lived in Taivoan community in nowadays Anping, Tainan and later founded two communities Tavakangh and Teopan in Xinhua. As invaded by Siraya people, Taivoan were later forced to migrate to Zuojhen and Shanshang, establishing two communities Makang and Kogimauwang respectively. The indigenous people were later driven by Siraya again and migrate to Danei, setting up the community Nounamou (Nunamu). Siraya eventually invaded Danei and forced Taivoan to move to Yujing, where Taivoan later founded four of their most important communities, Tevorangh, Sia-urie, Vogavon, and Kapoa.[15]

Historical Documents

According to the Dutch records in the 17th century, the Taivoan were settled in four main nations or tribes around the Yuchin Basin,[16] and therefore they had been called Shisha (四社熟番, literally "four tribes") in the history of Taiwan.

- Tevorangh (大武壠社), also spelled as Tevorang, Tivorangh, or Tevurang. This includes:[17]

- Sia-urie (also Siyauri, Sauli, 霄里社)

- Vogavon (also Voungo Voungor, bongabong [< bo𝛈abo𝛈], 芒仔芒社)

- Kapoa (also Kapowa, 茄拔社)

Besides the four main tribes, the Taivoan had founded the following tribes or nations in their history, according to Huang Shujing (黃叔璥), a Chinese imperial emissary of Taiwan, in his “Records from the mission to Taiwan and its Strait" (臺海使槎錄) (1722):[19]

- Tapani (噍吧哖社)

- A second tribe of Tevorangh (大武壠二社)

- Makang (木岡社)

- Maopao (茅匏社)

- Mongmingming (夢明明社)

- A sub-tribe of Tevorangh (大武壠派社), today Liuchongxi.

Citing Japanese linguist Shigeru Tsuchida, Taiwanese linguist Li, Paul Jen-kuei concluded that some areas previously considered as Siraya-speaking areas should be Taivoan-speaking areas, according to their recent research results on the Sinckan Manuscripts:[1][13]

- Wanli (灣裡)

- Wankhu (灣丘)

- Kiothaotseng (橋頭莊)

- Matau (麻豆)

A small community located between Wanli and Tevorangh[18] could be a Taivoan community, too:

- Terrijverrrijvagangh

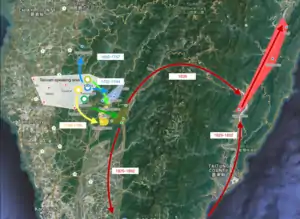

Population dispersal

After Koxinga defeated the Dutch colonists in Dutch Formosa, more Chinese immigrants flooded into Southern Taiwan, in turn driving Siraya people to inland Tainan. This resulted in the dispersal of Taivoan people from lowland to hilly areas in Tainan and Kaohsiung in the 18th century.[2][20] Some Taivoan had climbed across Wu Mt. (烏山) and reached Alikuan (阿里關) between 1722-1744[17] As a result, today all the indigenous people in Yuchin Basin, the native habitat of the Taivoan, recognize themselves as ethnically "Siraya", while many Taivoan descendants still have strong Taivoan identity across new habitats founded after the 18th century, including:[5][17]

Tainan

- Liuchongxi (六重溪), founded by Tevorangh-Taivoan between 1650–1757.[2]

- Khetang (溪東), founded by Tevorangh-Taivoan. The local Taivoan were forced to relocate since Nanhua Dam were to be built in the 1980s.

Kaohsiung

- Alikuan (阿里關), founded by Tevorangh-Taivoan from Khetang.

- Xiaolin (小林村), founded by Tevorangh-Taivoan from Alikuan in the late 19th century.

- Pualiao (匏仔寮), mainly founded by Kapoa-Taivoan, joined by many Tevorangh-Taivoan from Xiaolin through inter-tribal marriage since the early 20th century.

- Tuakhuhenn (大丘園), founded by Kapoa-Taivoan.

- Tingkongkuan (頂公館), founded by Kapoa-Taivoan.

- Hakongkuan (下公館), founded by Kapoa-Taivoan.

- Suannsamna (山杉林), founded by Siaurie-Taivoan after 1736.

- Pangliao (枋寮), founded by Vogavon-Taivoan after 1761.

- Lakku (六龜), founded by Vogavon-Taivoan from Pangliao.

- Laulong (荖濃), founded by Vogavon-Taivoan after 1781.

After a fatal landslide caused by typhoon Morakot destroyed Xiaolin on August 9, 2009, the local villagers, mainly Taivoan people, were compelled to relocate to three new communities:[5]

- Wulipu (五里埔), founded on January 15, 2011.

- Sunlight Xiaolin (日光小林), founded on December 24, 2011.

- Xiao'ai Xiaolin (小愛小林), founded on February 11, 2010.

Hualien

- Dazhuang (大庄), founded by Makatao and Taivoan people as the ethnic majority from Kaohsiung and Pingtung in the early 19th century, joined by very few Siraya people from Sinckan, Tainan, proven by the self-identification as "Taivoan", "Tau", "Makatau", or "Taiburan" by the local indigenous people in the early 20th century.[1] Local ancestral worship marks strong Taivoan religious influence, and many locals claim they have ancestors from Xiaolin.[21]

- Yuli (玉里)

- Guanyinshan (觀音山)

- Majialu (馬加祿)

- Wanning (萬寧)

- Luoshan (羅山)

- Mingli (明里)

- Funan (富南)

Culture

Taivoan language

The concept that Taivoan spoke the Siraya language has been rejected by many linguists, based on documentary and linguistic evidence. Since the January 2019 code release, SIL International has recognized Taivoan as an independent language and assigned the code tvx.[22]

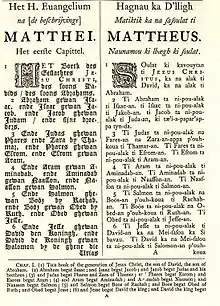

Documentary evidence

"De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia" by the Dutch in the 17th century showed that, to communicate with the chieftain of Cannacannavo (Kanakanavu), the local official language Sinccan (Siraya) had to be translated to Tarrocquan (regarded as a dialect of Rukai or Paiwan), and Tevorang (Taivoan):[23]

"...... in Cannacannavo: Aloelavaos tot welcken de vertolckinge in Sinccans, Tarrocquans en Tevorangs geschiede, weder voor een jaer aengenomen"

— "De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia", pp.6-8

Linguistic evidence

Taiwanese linguist Paul Jen-kuei Li and Japanese linguist Shigeru Tsuchida compared the corpora of the Gospel of St. Matthew in "Siraya", the Sinckan Manuscripts, and other corpora recorded by Japanese scholars in the early 20th century, and found some significant sound and morphological changes among Siraya, Taivoan, and Makatao, by which they think the Gospel of St. Matthew written by the Dutch people in the 17th century in Taiwan, having long been regarded as in the Siraya language, had actually been written in the Taivoan language:[12][13][24]

| Siraya | Taivoan | Makatao | PAn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sound change (1) | r | Ø~h | r | < *l |

| Sound change (2) | l | l | n | < *N |

| Sound change (3) | s | r, d | r, d | < *D, *d |

| Sound change (4) | -k-

-g- |

Ø

Ø |

-k-

---- |

< *k

< *S |

| Morphological change

(suffices for future tense) |

-ali | -ah | -ani |

Banana colloquial speech

The Taivoan people from Xiaolin, Alikuan, Pualiao in Kaohsiung, and Liuchongxi in Tainan have developed a mixed language called Banana colloquial speech (Chinese: 香蕉白話), in which the speakers input certain vowels and consonants in their mother tongues, whether Taiwanese or Taivoan, and generate a totally different speech. It is said the speech was developed during the rebellion of the Taivoan against Japanese colonial government during the early 20th century so that the Japanese could not understand what the Taivoan were saying.[5]

Some examples of Banana colloquial speech still spoken among very few Taivoan people in Xiaolin and Pualiao:[5]

| Translation | Native language | Original phrase | Banana colloquial speech |

|---|---|---|---|

| Welcome! (lit. Sit down please!) | Taivoan | Miunun | Misiunsununsun |

| Thank you, goodbye (lit. beautiful) | Taivoan | Makahanru | Masakasahansanrusu |

| I | Taiwanese | guá | guasua |

| you | Taiwanese | lí | lisi |

| s/he | Taiwanese | i | isi |

| the Shrine | Taiwanese | kon-kài | konsonkaisai |

| hand | Taiwanese | tshiú | tshiusiu |

"Local Lingua Franca" in Lakku

In Aug 1970, Japanese linguist Shigeru Tsuchida was told by one of his consultants that there was a Taivoan language in Lakkuli, such as:[25]

"ancua ikasu akia tavoLaa gwaa no miaa"

(Translation: Why don't you know my name?)

"ikuu ka ku boo pakciu cima vo tavLaa"

(Translation: I haven't seen you for a long time, so I don't know who you are.)

According to the scarce corpora Tsuchida obtained, he doubted the language is apparently a mixture of Kanakanabu, Taiwanese, Mantauran-Rukai, Bunun, Japanese, and some unknown elements.[25]

Religion

Modern-day Taivoan people simultaneously practice traditional animism and Taoism influenced by Chinese immigrants, while only very few Taivoans practice Buddhism and Christianity. As a result, none of modern Taivoan communities, including Xiaolin, Alikuan, Pualiao, and Tuakhuhenn, has founded any church, compared to 83.94% of Taiwanese Highland indigenous people who have been converted into Christianity;[26] only one of the 700-plus communities of the Taiwanese Highland indigenous people lacks a church.[27][28]

In Taivoan animism, the most important religious concept is Hiang or Xiang (transliterated as 向 in Taiwanese), which cannot be translated literally but conveys the idea of sorcery, taboo, and magic.[2][5] Any important religious articles related to Taivoan animism could be titled "Hiang", e.g. the wine and water blessed by the Highest Ancestral Spirits are called Hiang-tsiú (向酒, literally "Hiang-wine"; Taivoan: mimaw rarom) and Hiang-tsuí (向水, literally "Hiang-water"; Taivoan: mimaw palinlin), the bamboo erected in front of the Shrine for the Highest Ancestral Spirits to land onto the world is called Hiang-tik (向竹, literally "Hiang-bamboo"; Taivoan: malubiw), and the religious instrument made out of fishing trap to worship to the Highest Ancestral Spirits is called Hiang-Kô (向笱, literally "Hiang-fishing-trap"; Taivoan: agicin or kikiz).[5]

The Taivoan Night Ceremony is held on the full-moon of the ninth lunar month every year. The six months following the Night Ceremony are called Khui-Hiang (開向, literally "lift the taboo"), when the indigenous people can practice hunting, wedding, and singing several religious songs, until the six-month Kìm-Hiang (禁向, literally, "taboo undertaken") takes place on the full-moon of the third lunar month the next year, when all the hunting and wedding practices are prohibited, and several religious songs should not be sung, until the next Khui-Hiang comes again.[5]

Ceremonies and festivals

Night Ceremony

Many religious ceremonies used to be practiced by the Taivoan people, including Paka-taramay in Laulong, Too' pulaw, Samaok, and Kìm-Hiang in Alikuan and Xiaolin, but only the Night Ceremony along with Khui-Hiang are still in practice among Taivoan communities nowadays on the full-moon of the ninth lunar month every year.[29][30][31][32]

The Night Ceremony (Chinese: 夜祭) is not only the day to lift the taboo (Khui-Hiang) but also the most important day for all the Taivoan people to worship their Highest Ancestral Spirits. The Highest Ancestral Spirits used to be called Anag in Taivoan but are now commonly called Thài-Tsóo (太祖, literally "the Grandmothers"; Taivoan: Anag) or Huan-Thài-Tsóo (番太祖, literally "the Indigenous Grandmothers") in Taiwanese. Also, some Taivoan elders refer to the Highest Ancestral Spirits as Kuba-Tsóo, literally "the Grandmothers in Kuba", as Kuba is the Taivoan word for the Shrine.[5]

Many rituals or religious activities are or used to be practiced on the day of the Night Ceremony, including:[2][5][31][29]

- Patahim (also Patahin or Tataheng): A running race which used to be practiced by the Taivoan young men to show their manhood and also as the men's training. Now Patahim is open to the indigenous people of all genders and ages.

- Too' pulaw: A religious practice in which the Taivoan people exchanged bottle gourds after Patahim. No longer practiced.

- Samaok: A religious practice in which the Taivoan boys and girls chased each other after Patahim. No longer practiced.

- Malubiw-erection: A thorny bamboo (Bambusa stenostachya Hackel) called Malubiw is erected in front of the Shrine as the ladder for the Highest Ancestral Spirits to land onto the earth.

- Unaunaw (also 牽戲 or Khan-Hì in Taiwanese): A religious practice in which all the Taivoans, holding hands, sing and dance to religious songs in a large circle in front of the Shrine in the evening, commonly regarded as the highlight of the Night Ceremony.

The Taivoan communities that still practice the Night Ceremonies are:[32][33]

- Kaohisung

- Xiaolin

- Alikuan

- Laulong

Hualien

Tainan

- Liuchongxi

Women's Night

While many Taiwanese indigenous peoples are regarded as matrilineal societies, only Taivoan in Xiaolin and Pinuyumayan people hold a specific traditional ceremony or holiday for the women.[34][35][36] Many regard the two cheerful festivals for women only as legacies of the matrilineal practices of Taivoan and Pinuyumayan.[37][38][39]

Decades ago, the Women's Night (Chinese: 查某暝) used to start from 8:00 pm or 9:00 pm on the full-moon of the first lunar month in Xiaolin, when all the local Taivoan women dressed beautifully, played games, and sang and danced in the streets.[36] That evening, the Taivoan women could play games with the men or ask for money or cigarettes from a man,[36] and the man could not refuse or get angry.

During Japanese rule, the women's night was considered a direct challenge to the patriarchy of the wider society by the Japanese government, and therefore the festival was dissuaded and prohibited by the Japanese police officers and teachers from 1940,[5][40] according to the elders. Not until 2014 did the Taivoan people begin to revive the festival in Sunlight Xiaolin.[5][41]

Taivoan Cultural Festival

The Taivoan Cultural Festival (Chinese: 大武壠歌舞文化節) has been held by the Taivoan residents in Sunlight Xiaolin in spring annually since 2015, both in the hopes of reviving and promoting the culture of Taivoan, especially traditional Taivoan music, and to strengthen self-recognition among Taivoan people in the Kaohsiung area.[42]

Bamboo basket

A notable handicraft of Taivoan is bamboo basket (Taivoan: agicin or kikiz); it is used not only for fishing but also for religious purpose in Taivoan culture. As fishing trap is not uncommon among different Taiwanese indigenous peoples, Taivoan people are the only ones who sanctify bamboo fishing basket and grant it an important role at all levels of religious activity.[5]

Every Taivoan Shrine (Taivoan: Kuba, Kuva, or Kuwa) has a kogitanta agisen (Chinese: 向神座; lit. 'Seat of Hiang Deities') in the middle of the Shrine, which is a combination of an agicin and the central axial column (Taivoan: Kayu, literally "tree, wood") of the Shrine. Taivoan people consider kogitanta agisen to be the place where the Highest Ancestral Spirits rest and the most sacred space inside the Shrine. As a common bamboo basket can be made of any kind of bamboo, a kogitanta agisen must be made of thorny bamboo (Bambusa stenostachya Hackel), implying its sanctity.[5]

Embroidery

Embroidery is one of the most notable handicrafts of Taivoan people, unique by its variety of decorative patterns and colours, and making a significant cultural identification different from indigenous peoples nearby, e.g. Cou, Bunun, Rukai, and Siraya.[4]

Some common patterns found in Taivoan embroideries are:[4]

- Square or diamond shapes

- Thistle flowers (Taivoan: ayxaw)

- Extended diamond shapes

- Straight lines and mountain shapes

- Abstract geometric shapes

- Geometric flowers and leaves

- Geometric human faces and figures

- Insects, birds, and snakes

- Human-in-boat shapes

- Other geometric shapes like swastikas

The thistle flowers in Taivoan embroidery are the most unique, not seen in any other Taiwanese indigenous arts. Some local Taivoan people believe the thistle flower patterns stand for Cirsium lineare (Thunb.) Sch. Bip native to Jiasian, Kaohsiung, and some say they are globe amaranths (Gomphrena globosa L).[4][5]

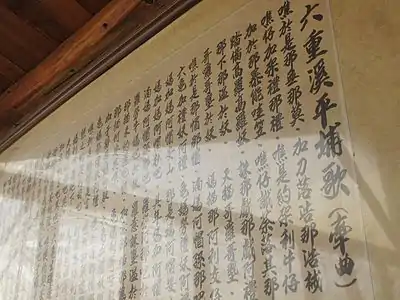

Music

Taivoan people own some of the most abundant folk music among all the Taiwanese Plain indigenous peoples, ranging from hymns for the Highest Ancestral Spirits that can only be sung in front of the Shrine or during Khui-Hiang, to antiphonal work songs mocking Chinese immigrants.[43] Many of these have been recorded and even taught in local elementary schools in Taivoan communities.[44]

Taboro

Taboro, or the so-called "the Song in the Shrine" among the Taivoan people, is a ceremonial song that can be sung only in the Shrine at the Night Ceremony; singing on any other occasion is strictly prohibited.[5]

Kalawahe

Kalawahe, or the so-called "Out-of-the-Shrine Song" among the Taivoan people, is a ceremonial song that is normally sung when the indigenous people are walking out of the Shrine after worshiping to the Highest Ancestral Spirits at the Night Ceremony.[45]

Some of the lyrics are:[45]

Wa-he. Manie, he mahanru e, he kalawahe, wa-he.

Talaloma e, he talaloma e, he kalawahe, wa-he.

Tamaku e, he tamaku e, he kalawahe, wa-he.

Saviki e, he saviki e, he kalawahe, wa-he.

Rarom he, he rarom he, he kalawahe, wa-he.

As Taivoan language hasn't been in use for nearly a century,[12] many ceremonial songs like "Kalawahe" can hardly be fully understood, but people could still try to catch a rough idea from some of the lyrics and the occasion of the song that it's about worship of the Highest Ancestral Spirits, e.g. tamaku "cigarette", saviki "betel nut", and rarom "water" that appear in the song are all the necessary offerings to the Highest Ancestral Spirits.[5][45][46]

Lawkhema

Lawkhema is a cheerful Taivoan work song among men and women while working in mountains. While most of the lyrics are in Taivoan, the word "Lawkhema" (literally "Old Hen", implying a stingy person in Hakka Chinese) that appears in the song repeatedly is a Hakka Chinese term that the singers sing to mock Hakka people, showing the negative stereotype believed by many Taivoan people that the immigrants are mean and stingy.[45]

Writings

Gospel of St. Matthew

The earliest written works in Taivoan language are "Hagnau ka d'llig matiktik, ka na Sasoulat ti Mattheus, ti Johannes appa.",[47] titled "Het Heylige Euangelium Matthei En Joannis / oft: Overgeset Inde Formosansche Tale, Voor De Inwoonders Van Soulang, Mattau, Sinckan, Bacloan, Tavokan, En Tevorang" in Dutch, the Gospel of St. Matthew translated into Taivoan and Siraya in 1661. Although the writing is credited to Dutch missionary Daniel Gravius, recent linguistic research results have shown that it "was not the product of one person only: this is clear from the text itself, and [...] that there was a committee deciding over the final edition",[13] as different languages, i.e. Taivoan and Siraya, are found in it.

An example of the Gospel of St. Matthew in Taivoan:[48]

Tou kidi k'anna ni-matta-naunamou ta ti Jesus matta-sasou, mattœ'i-k'ma-hynna, Si-lala, pa-salikough-â ki vanna-oumi ki ryh, ka ni-mou-touk ta pei-sasou-an ki tounnoun ki vullu-vullum.

(Translation: From that time Jesus began to preach and to say, "Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is near".)

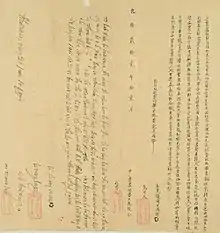

Sinckan Manuscripts

Many leases, mortgages, and other commerce contracts written in Siraya, Taivoan, and Makatao have been found among the communities in Southern Taiwan in the past one century, written in the Roman script taught by the Dutch missionaries. As most of the manuscripts are in the language of Sinckan or Siraya, they are called the Sinckan Manuscripts (新港文書) in combination.[24]

An example of the Sinckan Manuscripts written in Taivoan:[13]

lip san kih lang tausiah tamoring san to lagalaij san 5 o koh hiro to panah san 5 ki koh. komma ta na-ga-girah ti tanbingan. ki banitok 204 nio hon gin. komma ta solat kata, na inni imdaij.

(Translation: The contractor Tamoring from Tausiah has 5 units of farmland located in Lagalaij and 5 units of farmland located in Panah to be traded with Tan Bingan for 24 taels of indigenous silver. Thus written the contract, agreed by all the Inni's.)

Folklore

Not much folklore has been retained by modern-day Taivoan communities. Two examples of folklore that are still well-known even to the younger Taivoan generations are:[5]

Soldiers of Hiang-Water

Taivoan people believe in the supernatural power of mimaw-pilinlin or Hiang-water, the water blessed by the Highest Ancestral Spirits. In Xiaolin, it is said when the local Taivoans in rebellion were escaping from the pursuit of Japanese army, the Hiang-water spilled out by them transformed into hundreds of soldiers, helping them defeat the Japanese.

Ancestral Spirit That Escaped

Taivoan people in Pualiao believe the forms of the local Highest Ancestral Spirits were seven pearls that flew back to the village only during the Night Ceremony. Decades ago, when a Taoist deity from Pingtung came by Pualiao and was trying to subdue the Highest Ancestral Spirits, the youngest of the seven spirits transformed into a pearl and escaped successfully. The local Taivoans believe the youngest spirit is still hiding on a certain tree in Pualiao.

Nomenclature

Many Taivoan names and surnames are found in the Sinckan Manuscripts, mainly from the manuscripts found in the communities of Matau, Wanli, and Tevorangh.[23][13][18]

Matau

- Lariti

- Lohraong

- Palaong

- Pali / Pani

- Piah

- Salo / Saro

- Sautok

- Tapinahi

- Tavila / Tvilah / Tvila

- Vangol

- Vil

- Vila / Vilah

Terrijverrrijvagangh

- Covol

Tevorangh

|

|

|

Tamani

- Dapare

Wanli

|

|

|

Matau

|

|

|

|

Terrijverrrijvagangh

- Dorap

- Notes

- (m) stands for male name and (f) for female names.[49]

Modern surnames

Due to close contact with Chinese immigrants in Southern Taiwan, Taivoan people have been influenced by Chinese culture and have adopted Chinese surnames. Certain Chinese surnames are more common than others among different Taivoan communities:[50]

| Taivoan communities | Common Surnames Adopted by the Taivoans | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xiaolin | Pan (潘) | Liu (劉) | Wang (王) | Mao (毛) | Xu (徐) | |||||

| Alikuan | Pan | Liu | Wang | Jin (金) | ||||||

| Laulong | Pan | Liu | Jin | Xiang (向) | ||||||

| Tuakhuhenn | Pan | Liu | Wang | |||||||

| Pualiao | Pan | Liu | Wang | Jin | Ye (葉) | |||||

| Pangliao | Pan | Liu | Yang (楊) | Jiang (江) | ||||||

| Suannsamna | Pan | Liu | Jiang | |||||||

| Lakku | Pan | Liu | ||||||||

| Baktsu | Pan | Liu | ||||||||

| Pehtsuitsuann | Pan | Liu | Wang | |||||||

Pan (潘) is the most dominant Chinese surname, adopted by almost all the Taiwanese Plain indigenous people, as the character means "indigenous people (番) living by the water (氵)". It is the counterpart of Kao (高) for the Taiwanese Highland indigenous people, which means "high (高)".[51]

As almost all of the Taiwanese Plain indigenous peoples speak Taiwanese in daily life, it is almost impossible to tell which ethnic group they are from simply by the languages spoken.[5] Sometimes the surnames give a clue for an outsider; for example, one can guess a member from the Bang family in Xiaolin should have Siraya ancestry instead of Taivoan, as Bang (邦) is a dominant Chinese surname in many Siraya communities, where the surnames like Pan and Liu that are common among Taivoan communities can hardly be found.[50]

Gallery

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taivoan people. |

The Night Ceremony of Taivoan in Dazhuang, Hualien

The Night Ceremony of Taivoan in Dazhuang, Hualien The Shrine of Taivoan in Dazhuang, Hualien

The Shrine of Taivoan in Dazhuang, Hualien The Shrine of Taivoan in Laonong, Kaohsiung

The Shrine of Taivoan in Laonong, Kaohsiung The Shrine of Taivoan in Liuchongxi, Tainan

The Shrine of Taivoan in Liuchongxi, Tainan Taivoan people in traditional dress at the Night Ceremony in Xiaolin

Taivoan people in traditional dress at the Night Ceremony in Xiaolin Taivoan people in Xiaolin offer to the ancestral spirits at the Shrine at the Night Ceremony

Taivoan people in Xiaolin offer to the ancestral spirits at the Shrine at the Night Ceremony Taivoan Dance Theatre performing traditional song and dance

Taivoan Dance Theatre performing traditional song and dance Taivoan ceremonial song transliterated in Chinese characters in the Shrine of Liuchongxi, Tainan

Taivoan ceremonial song transliterated in Chinese characters in the Shrine of Liuchongxi, Tainan

References

- Tsuchida, Shigeru; Yamada, Yukihiro; Moriguchi, Tsunekazu (1991). Linguistic Materials of the Formosan Sinicized Populations I: Siraya and Basai. The University of Tokyo Department of Linguistics. p. 29.

- Alak, Akatuang (2013). 阿立祖信仰研究. Tainan: Cultural Affairs Bureau, Tainan City Government. pp. 21, 25–33, 44, 134, 162–164, 190. ISBN 978-986-03-9416-0.

- "首次大武壠族跨部落族群共識會議聲明稿 (Consensus Statement of the 1st Inter-tribal Consensus Conference of Taivoan People)". Mahanru Taivoan. 2016-10-06. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- Hu, Chia-yu (2014). Threads of Splendor - Taivoan Pingpu Clothes and Embroidery Collections. Kaohsiung: Kaohsiung Museum of History. ISBN 978-957-801-635-4.

- 種回小林村的記憶 : 大武壠民族植物暨部落傳承400年人文誌 (A 400-Year Memory of Xiaolin Taivoan: Their Botany, Their History, and Their People). Kaohsiung City: 高雄市杉林區日光小林社區發展協會 (Sunrise Xiaolin Community Development Association). 2017. ISBN 978-986-95852-0-0.

- Candidius, George. Discours ende Cort verhaal, van't Eylant Formosa, ondersocht ende beschreven, door den Eerwaardingen.

- Ferrell, Raleigh (1971). "Aboriginal peoples of the Southwestern Taiwan plains". Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology. 32: 217–235.

- Gao, Gong-qian (1694). Taiwan Prefecture Gazetteer. p. 15.

- Yen, Teen-yu (2015). "A Preliminary Study of the Relationship between the Liaosong Culture and the Xilaya People and the Changes in Their Society and Culture", 臺灣史前史專論, p.258. Taipei: 中央研究院、聯經出版公司.

- Wong, Jiayin (2011-09-24). "麻豆社事件 (Mattau Incident)". 台灣故事館. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- "麻豆協約◎福爾摩沙第一份簽署的主權讓渡和約 (Mattau Act, the First Sovereignty Grant Act Signed in Formosa)". E大調. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- Li, Paul Jen-kuei (2010). 珍惜台灣南島語言. 前衛出版. pp. 159–182. ISBN 978-957-801-635-4.

- Paul Jun-kuei, Li (2010). Studies of Sinkang Manuscript. Taipei: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica. pp. 7–24, 353. ISBN 978-986-02-3342-1.

- Zhang, Yaoqi (2003). 臺灣平埔族社名硏究. ISBN 9574109895.

- Cheng-yuan, Liu; Wen-ming, Chien; Ming-liang, Wang (2018). 大武壠——人群移動、信仰與歌謠復振 (Taivoan, the People's Dispersion, Religion, and Revitalization of Songs). Kaohsiung: Kaohsiung Museum of History. ISBN 9789860574821.

- 張, 溪南 (1998). 白河鎮志. 臺南縣白河鎮公所. p. 57.

- Hung, Li-wan (2011). "Ethnic Interaction, Migration and Expanded Living Space of Shufan in Mountain Peripheral Areas of Jia Nan Plain during Qing Dynasty: A Study of Duo-luo-guo-she". Taipei: Institute of Taiwan History.

- Kang, Pei-te (2010-03-01). "Tribal Consolidation of Formosan Austronesians under Dutch East India Company" (PDF). Taiwan Historical Research. 17–1: 1–25.

- Huang, Shujing (1722). 臺海使槎錄 (Records from the mission to Taiwan and its Strait).

- Lin, Ming-yuan (2016). "Immigrants' Settlement and Industrious Changes of Jiasian District", pp.2-3. Kaohsiung: National Kaohsiung Normal University.

- 張, 振岳 (2010). 大庄平埔西拉雅族文物圖說與民俗植物圖誌 (Illustrations of Cultural Relics and Ethnobotany of Pingpu Siraya in Dazhuang). Hualien: Hualien County Cultural Affairs Bureau. pp. 8–14. ISBN 978-986-02-5684-0.

- "639 Identifier Documentation: tvx". SIL International. 2019-01-25. Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia. 1629–1662.

- Adelaar, Alexander (2011). Siraya. Retrieving the Phonology, Grammar and Lexicon of a Dormant Formosan Language. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 9783110252958.

- Tsuchida, Shigeru. "Another Pepo Language: Taivoan or a Local Lingua Franca?" (PDF). The Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica. Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- 簡, 鴻模. "原住民族信仰基督宗教的比例有多少?" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- 蔣, 勳 (2005). 頭目哈古. Taipei: 聯經出版公司. p. 9. ISBN 9570828943.

- "Taiwan's Indigenous Peoples Portal". Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- Chen, Han-guang (1991). "六龜鄉荖濃村平埔族信仰調查 (A Study of the Religions of Plains Indigenous Peoples in Laulong, Lakku)". 高縣文獻 (Kaohsiung Historography). 11. ISSN 1727-4435.

- Chen, Han-guang (1991). "甲仙鄉匏仔寮平埔族宗教信仰調查 (A Study of the Religions of Plains Indigenous Peoples in Pualiao, Jiasian)". 高縣文獻 (Kaohsiung Historography). 11. ISSN 1727-4435.

- Chen, Han-guang (1991). "高雄縣阿里關及附近平埔族宗教信仰和習慣調查 (A Study of the Religions of Plains Indigenous Peoples around Aliguan, Kaohsiung)". 高縣文獻 (Kaohsiung Historography). 11. ISSN 1727-4435.

- "大武壠小林平埔夜祭 (The Night Ceremony of Taivoan Plain Indigenous People in Xiaolin)". Bureau of Cultural Affairs, Kaohsiung City Government. 2012-12-26. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- "10/19 禮拜六作夥來南台灣,看「台灣人」賽跑、聽「台灣人」唱牽曲,一起愛「台灣」啦!(Come to Southern Taiwan on 19th Oct for the Running Race and Round Dance of "Taiwan" people!)". Mata Taiwan. 2013-10-18. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- "卑南族婦女節 (The Women's Day of Pinuyumayan)". 臺灣女人 (The Women in Taiwan). Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- 范, 情 (2006). 戴上花冠,歡慶婦女節──Mugamut婦女除草完工祭(卑南族婦女節)(Wearing Wreathes, Celebrating for the Women's Day - Mugamus the Weeding Ceremony of Women (Pinuyumayan's Women's Day)). Taipei: 女書文化. pp. 56–73. ISBN 9578233612.

- Chien, Wen-ming (2008). "Cultural Property and Change: A Study of Xiaolin Pingpu Ethnic Belief in Traditional Deities and Spirits". 文化資產保存學刊. 5: 24–34.

- "西拉雅族查某瞑 (The Women's Night of Siraya)". National Alliance of Taiwan Women's Associations. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- "媽祖信仰/平埔族的「查某暝」/卑南族婦女節/「偷挽蔥,嫁好尪」─元宵挽蔥習俗 (Mazu, "Women's Night" of Plain Indigenous People, Women's Day of Pinuyumayan, "Steal Spring Onion for a Good Husband" the Custom on the First Full Moon Festival)". 姜朝鳳宗族. 2014-11-24. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- "元宵夜揪竟發生什麼事,讓女人不睡瘋整夜!(What Happens on the First Full Moon Festival that Women Stay Up All the Night)". Mahanru Taivoan. 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- "平埔族的「查某暝」(The Women's Night of the Plain Indigenous People)". 臺灣女人 (The Women of Taiwan). Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- 范, 情 (2006). "元宵暝,查某醒歸暝──西拉雅族查某暝 (Women's Night, Women Awaken All the Night - The Women's Night of Siraya)". 女人屐痕:臺灣女性文化地標. Taipei: 女書文化. pp. 44–55. ISBN 9578233612.

- "陳菊,我們也是原住民!小林村大武壠歌舞文化節籲早日正名 (We are indigenous people, too! Xiaolin Taivoan Cultural Festival Appealing for Indigenous Recognition)". Mahanru Taivoan. 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- 太祖的孩子-大武壠族古謠巡迴音樂會 ("Children of Taizu", the Tour Concert of Traditional Songs of Taivoan). Kaohsiung: Taivoan Theatre. 2017.

- "傳承大武壠文化 大滿舞團教童唱古謠 (Taivoan Theatre Teaching Traditional Songs in Elementary Schools for Taivoan Cultural Preservation)". Taiwan Indigenous Television. 2016-09-29. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- 歡喜來牽戱 (Let's Dance a Round Dance). Kaohsiung: 大滿舞團 (Taivoan Dance Theatre). 2015.

- Lin, Ging-cai. 從歌謠看西拉雅族聚落與族群 (A Glance of Siraya peoples and communities from the Songs). 平埔文化資訊網.

- Li, Paul Jen-kuei (2010). 從文獻資料看台灣平埔族群的語言 (Languages of Taiwanese Plain Indigenous Peoples in Early Documents). Taipei: 中央研究院.

- Daniel, Gravius (2004). Notes on The Gospel According to Matthew in Formosan Siraya Dialect. Translated by Chen, Bien-horn. Taipei: Bien-Horn Chen. p. 41.

- Paul Jun-kuei, Li (2010). Studies of Sinkang Manuscript. Taipei: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica. ISBN 978-986-02-3342-1.

- "是不是平埔原住民該看DNA還是手臂那條線?3分鐘懶人包出爐,讓我們立刻尋根去!". Mata Taiwan. 2016-07-29. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- "泰雅族的命名文化──子父聯名 (Traditional Naming Culture of Tayal)". 每日一冷. 2015-04-27. Retrieved 2018-02-08.