Dynamic equilibrium

In chemistry, and in physics, a dynamic equilibrium exists once a reversible reaction occurs. Substances transition between the reactants and products at equal rates, meaning there is no net change. Reactants and products are formed at such a rate that the concentration of neither changes. It is a particular example of a system in a steady state. In thermodynamics, a closed system is in thermodynamic equilibrium when reactions occur at such rates that the composition of the mixture does not change with time. Reactions do in fact occur, sometimes vigorously, but to such an extent that changes in composition cannot be observed. Equilibrium constants can be expressed in terms of the rate constants for reversible reactions.

Examples

In a new bottle of soda the concentration of carbon dioxide in the liquid phase has a particular value. If half of the liquid is poured out and the bottle is sealed, carbon dioxide will leave the liquid phase at an ever-decreasing rate and the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the gas phase will increase until equilibrium is reached. At that point, due to thermal motion, a molecule of CO2 may leave the liquid phase, but within a very short time another molecule of CO2 will pass from the gas to the liquid, and vice versa. At equilibrium the rate of transfer of CO2 from the gas to the liquid phase is equal to the rate from liquid to gas. In this case, the equilibrium concentration of CO2 in the liquid is given by Henry's law, which states that the solubility of a gas in a liquid is directly proportional to the partial pressure of that gas above the liquid.[1] This relationship is written as

where k is a temperature-dependent constant, p is the partial pressure and c is the concentration of the dissolved gas in the liquid. Thus the partial pressure of CO2 in the gas has increased until Henry's law is obeyed. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the liquid has decreased and the drink has lost some of its fizz.

Henry's law may be derived by setting the chemical potentials of carbon dioxide in the two phases to be equal to each other. Equality of chemical potential defines chemical equilibrium. Other constants for dynamic equilibrium involving phase changes, include partition coefficient and solubility product. Raoult's law defines the equilibrium vapor pressure of an ideal solution

Dynamic equilibrium can also exist in a single-phase system. A simple example occurs with acid-base equilibrium such as the dissociation of acetic acid, in aqueous solution.

- CH3CO2H CH3CO2− + H+

At equilibrium the concentration quotient, K, the acid dissociation constant, is constant (subject to some conditions)

In this case, the forward reaction involves the liberation of some protons from acetic acid molecules and the backward reaction involves the formation of acetic acid molecules when an acetate ion accepts a proton. Equilibrium is attained when the sum of chemical potentials of the species on the left-hand side of the equilibrium expression is equal to the sum of chemical potentials of the species on the right-hand side. At the same time the rates of forward and backward reactions are equal to each other. Equilibria involving the formation of chemical complexes are also dynamic equilibria and concentrations are governed by the stability constants of complexes.

Dynamic equilibria can also occur in the gas phase as, for example, when nitrogen dioxide dimerizes.

- 2NO2 N2O4;

In the gas phase, square brackets indicate partial pressure. Alternatively, the partial pressure of a substance may be written as P(substance).[2]

Relationship between equilibrium and rate constants

In a simple reaction such as the isomerization:

there are two reactions to consider, the forward reaction in which the species A is converted into B and the backward reaction in which B is converted into A. If both reactions are elementary reactions, then the rate of reaction is given by[3]

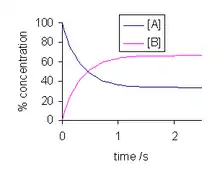

where kf is the rate constant for the forward reaction and kb is the rate constant for the backward reaction and the square brackets, [..] denote concentration . If only A is present at the beginning, time t=0, with a concentration [A]0, the sum of the two concentrations, [A]t and [B]t, at time t, will be equal to [A]0.

The solution to this differential equation is

and is illustrated at the right. As time tends towards infinity, the concentrations [A]t and [B]t tend towards constant values. Let t approach infinity, that is, t→∞, in the expression above:

In practice, concentration changes will not be measurable after . Since the concentrations do not change thereafter, they are, by definition, equilibrium concentrations. Now, the equilibrium constant for the reaction is defined as

It follows that the equilibrium constant is numerically equal to the quotient of the rate constants.

In general they may be more than one forward reaction and more than one backward reaction. Atkins states[4] that, for a general reaction, the overall equilibrium constant is related to the rate constants of the elementary reactions by

- .

References

Atkins, P.W.; de Paula, J. (2006). Physical Chemistry (8th. ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870072-5.

- Atkins, Section 5.3

- Denbeigh, K (1981). The principles of chemical equilibrium (4th. ed.). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-28150-4.

- Atkins, Section 22.4

- Atkins, Section 22.4