Partial pressure

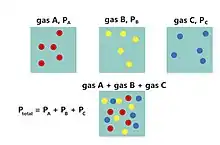

In a mixture of gases, each constituent gas has a partial pressure which is the notional pressure of that constituent gas if it alone occupied the entire volume of the original mixture at the same temperature.[1] The total pressure of an ideal gas mixture is the sum of the partial pressures of the gases in the mixture (Dalton's Law).

The partial pressure of a gas is a measure of thermodynamic activity of the gas's molecules. Gases dissolve, diffuse, and react according to their partial pressures, and not according to their concentrations in gas mixtures or liquids. This general property of gases is also true in chemical reactions of gases in biology. For example, the necessary amount of oxygen for human respiration, and the amount that is toxic, is set by the partial pressure of oxygen alone. This is true across a very wide range of different concentrations of oxygen present in various inhaled breathing gases or dissolved in blood.[2] The partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide are important parameters in tests of arterial blood gases, but can also be measured in, for example, cerebrospinal fluid.

Symbol

The symbol for pressure is usually P or p which may use a subscript to identify the pressure, and gas species are also referred to by subscript. When combined these subscripts are applied recursively.[3][4]

Examples:

- or = pressure at time 1

- or = partial pressure of hydrogen

- or = venous partial pressure of oxygen

Dalton's law of partial pressures

Dalton's law expresses the fact that the total pressure of a mixture of gases is equal to the sum of the partial pressures of the individual gases in the mixture.[5] This equality arises from the fact that in an ideal gas the molecules are so far apart that they do not interact with each other. Most actual real-world gases come very close to this ideal. For example, given an ideal gas mixture of nitrogen (N2), hydrogen (H2) and ammonia (NH3):

| where: | |

| = total pressure of the gas mixture | |

| = partial pressure of nitrogen (N2) | |

| = partial pressure of hydrogen (H2) | |

| = partial pressure of ammonia (NH3) |

Ideal gas mixtures

Ideally the ratio of partial pressures equals the ratio of the number of molecules. That is, the mole fraction of an individual gas component in an ideal gas mixture can be expressed in terms of the component's partial pressure or the moles of the component:

and the partial pressure of an individual gas component in an ideal gas can be obtained using this expression:

| where: | |

| = mole fraction of any individual gas component in a gas mixture | |

| = partial pressure of any individual gas component in a gas mixture | |

| = moles of any individual gas component in a gas mixture | |

| = total moles of the gas mixture | |

| = total pressure of the gas mixture |

The mole fraction of a gas component in a gas mixture is equal to the volumetric fraction of that component in a gas mixture.[6]

The ratio of partial pressures relies on the following isotherm relation:

-

- VX is the partial volume of any individual gas component (X)

- Vtot is the total volume of the gas mixture

- pX is the partial pressure of gas X

- ptot is the total pressure of the gas mixture

- nX is the amount of substance of gas (X)

- ntot is the total amount of substance in gas mixture

Partial volume (Amagat's law of additive volume)

The partial volume of a particular gas in a mixture is the volume of one component of the gas mixture. It is useful in gas mixtures, e.g. air, to focus on one particular gas component, e.g. oxygen.

It can be approximated both from partial pressure and molar fraction:[7]

-

- VX is the partial volume of an individual gas component X in the mixture

- Vtot is the total volume of the gas mixture

- pX is the partial pressure of gas X

- ptot is the total pressure of the gas mixture

- nX is the amount of substance of gas X

- ntot is the total amount of substance in the gas mixture

Vapor pressure

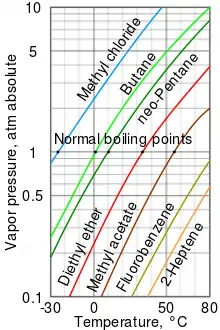

Vapor pressure is the pressure of a vapor in equilibrium with its non-vapor phases (i.e., liquid or solid). Most often the term is used to describe a liquid's tendency to evaporate. It is a measure of the tendency of molecules and atoms to escape from a liquid or a solid. A liquid's atmospheric pressure boiling point corresponds to the temperature at which its vapor pressure is equal to the surrounding atmospheric pressure and it is often called the normal boiling point.

The higher the vapor pressure of a liquid at a given temperature, the lower the normal boiling point of the liquid.

The vapor pressure chart displayed has graphs of the vapor pressures versus temperatures for a variety of liquids.[8] As can be seen in the chart, the liquids with the highest vapor pressures have the lowest normal boiling points.

For example, at any given temperature, methyl chloride has the highest vapor pressure of any of the liquids in the chart. It also has the lowest normal boiling point (−24.2 °C), which is where the vapor pressure curve of methyl chloride (the blue line) intersects the horizontal pressure line of one atmosphere (atm) of absolute vapor pressure. Note that at higher altitudes, the atmospheric pressure is less than that at sea level, so boiling points of liquids are reduced. At the top of Mount Everest, the atmospheric pressure is approximately 0.333 atm, so by using the graph, the boiling point of diethyl ether would be approximately 7.5 °C versus 34.6 °C at sea level (1 atm).

Equilibrium constants of reactions involving gas mixtures

It is possible to work out the equilibrium constant for a chemical reaction involving a mixture of gases given the partial pressure of each gas and the overall reaction formula. For a reversible reaction involving gas reactants and gas products, such as:

the equilibrium constant of the reaction would be:

| where: | |

| = the equilibrium constant of the reaction | |

| = coefficient of reactant | |

| = coefficient of reactant | |

| = coefficient of product | |

| = coefficient of product | |

| = the partial pressure of raised to the power of | |

| = the partial pressure of raised to the power of | |

| = the partial pressure of raised to the power of | |

| = the partial pressure of raised to the power of |

For reversible reactions, changes in the total pressure, temperature or reactant concentrations will shift the equilibrium so as to favor either the right or left side of the reaction in accordance with Le Chatelier's Principle. However, the reaction kinetics may either oppose or enhance the equilibrium shift. In some cases, the reaction kinetics may be the overriding factor to consider.

Henry's law and the solubility of gases

Gases will dissolve in liquids to an extent that is determined by the equilibrium between the undissolved gas and the gas that has dissolved in the liquid (called the solvent).[9] The equilibrium constant for that equilibrium is:

- (1)

where: = the equilibrium constant for the solvation process = partial pressure of gas in equilibrium with a solution containing some of the gas = the concentration of gas in the liquid solution

The form of the equilibrium constant shows that the concentration of a solute gas in a solution is directly proportional to the partial pressure of that gas above the solution. This statement is known as Henry's law and the equilibrium constant is quite often referred to as the Henry's law constant.[9][10][11]

Henry's law is sometimes written as:[12]

- (2)

where is also referred to as the Henry's law constant.[12] As can be seen by comparing equations (1) and (2) above, is the reciprocal of . Since both may be referred to as the Henry's law constant, readers of the technical literature must be quite careful to note which version of the Henry's law equation is being used.

Henry's law is an approximation that only applies for dilute, ideal solutions and for solutions where the liquid solvent does not react chemically with the gas being dissolved.

In diving breathing gases

In underwater diving the physiological effects of individual component gases of breathing gases is a function of partial pressure.

Using diving terms, partial pressure is calculated as:

- partial pressure = (total absolute pressure) × (volume fraction of gas component)

For the component gas "i":

- pi = P × Fi

For example, at 50 metres (164 ft) underwater, the total absolute pressure is 6 bar (600 kPa) (i.e., 1 bar of atmospheric pressure + 5 bar of water pressure) and the partial pressures of the main components of air, oxygen 21% by volume and nitrogen approximately 79% by volume are:

- pN2 = 6 bar × 0.79 = 4.7 bar absolute

- pO2 = 6 bar × 0.21 = 1.3 bar absolute

| where: | |

| pi | = partial pressure of gas component i = in the terms used in this article |

|---|---|

| P | = total pressure = in the terms used in this article |

| Fi | = volume fraction of gas component i = mole fraction, , in the terms used in this article |

| pN2 | = partial pressure of nitrogen = in the terms used in this article |

| pO2 | = partial pressure of oxygen = in the terms used in this article |

The minimum safe lower limit for the partial pressures of oxygen in a gas mixture is 0.16 bars (16 kPa) absolute. Hypoxia and sudden unconsciousness becomes a problem with an oxygen partial pressure of less than 0.16 bar absolute. Oxygen toxicity, involving convulsions, becomes a problem when oxygen partial pressure is too high. The NOAA Diving Manual recommends a maximum single exposure of 45 minutes at 1.6 bar absolute, of 120 minutes at 1.5 bar absolute, of 150 minutes at 1.4 bar absolute, of 180 minutes at 1.3 bar absolute and of 210 minutes at 1.2 bar absolute. Oxygen toxicity becomes a risk when these oxygen partial pressures and exposures are exceeded. The partial pressure of oxygen determines the maximum operating depth of a gas mixture.

Narcosis is a problem when breathing gases at high pressure. Typically, the maximum total partial pressure of narcotic gases used when planning for technical diving may be around 4.5 bar absolute, based on an equivalent narcotic depth of 35 metres (115 ft).

The effect of a toxic contaminant such as carbon monoxide in breathing gas is also related to the partial pressure when breathed. A mixture which may be relatively safe at the surface could be dangerously toxic at the maximum depth of a dive, or a tolerable level of carbon dioxide in the breathing loop of a diving rebreather may become intolerable within seconds during descent when the partial pressure rapidly increases, and could lead to panic or incapacitation of the diver.

In medicine

The partial pressures of particularly oxygen () and carbon dioxide () are important parameters in tests of arterial blood gases, but can also be measured in, for example, cerebrospinal fluid.

| Unit | Arterial blood gas | Venous blood gas | Cerebrospinal fluid | Alveolar pulmonary gas pressures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kPa | 11–13[13] | 4.0–5.3[13] | 5.3–5.9[13] | 14.2 | |

| mmHg | 75–100[14] | 30–40[15] | 40–44[16] | 107 | |

| kPa | 4.7–6.0[13] | 5.5–6.8[13] | 5.9–6.7[13] | 4.8 | |

| mmHg | 35–45[14] | 41–51[15] | 44–50[16] | 36 |

See also

- Breathing gas – Gas used for human respiration

- Henry's law – Relation of equilibrium solubility of a gas in a liquid to its partial pressure in the contacting gas phase

- Ideal gas – Mathematical model which approximates the behavior of real gases

- Ideal gas law – The equation of state of a hypothetical ideal gas

- Mole fraction – The proportion of a constituent to the total amount of all constituents in a mixture, expressed in mol/mol

- Mole (unit) – SI unit of amount of substance

- Vapor – A substances in the gas phase at a temperature lower than its critical point

References

- Charles Henrickson (2005). Chemistry. Cliffs Notes. ISBN 978-0-7645-7419-1.

- "Gas Pressure and Respiration". Lumen Learning.

- Staff. "Symbols and Units" (PDF). Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology : Guide for Authors. Elsevier. p. 1. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

All symbols referring to gas species are in subscript,

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "pressure, p". doi:10.1351/goldbook.P04819

- Dalton's Law of Partial Pressures

- Frostberg State University's "General Chemistry Online"

- Page 200 in: Medical biophysics. Flemming Cornelius. 6th Edition, 2008.

- Perry, R.H. and Green, D.W. (Editors) (1997). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-049841-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- An extensive list of Henry's law constants, and a conversion tool

- Francis L. Smith & Allan H. Harvey (September 2007). "Avoid Common Pitfalls When Using Henry's Law". CEP (Chemical Engineering Progress). ISSN 0360-7275.

- Introductory University Chemistry, Henry's Law and the Solubility of Gases Archived 2012-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "University of Arizona chemistry class notes". Archived from the original on 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2006-05-26.

- Derived from mmHg values using 0.133322 kPa/mmHg

- Normal Reference Range Table Archived 2011-12-25 at the Wayback Machine from The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Used in Interactive Case Study Companion to Pathologic basis of disease.

- The Medical Education Division of the Brookside Associates--> ABG (Arterial Blood Gas) Retrieved on Dec 6, 2009

- PATHOLOGY 425 CEREBROSPINAL FLUID [CSF] Archived 2012-02-22 at the Wayback Machine at the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the University of British Columbia. By Dr. G.P. Bondy. Retrieved November 2011