E. Pauline Johnson

Emily Pauline Johnson (10 March 1861 – 7 March 1913), also known by her Mohawk stage name Tekahionwake (pronounced dageh-eeon-wageh, literally 'double-life'),[1] was a Canadian poet, author, and performer who was popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Her father was a hereditary Mohawk chief of mixed ancestry and her mother was an English immigrant.[2]

E. Pauline Johnson | |

|---|---|

E. Pauline Johnson, c. 1885–1895 | |

| Born | Emily Pauline Johnson 10 March 1861 Six Nations, Ontario |

| Died | 7 March 1913 (aged 51) Vancouver, British Columbia |

| Resting place | Stanley Park, Vancouver |

| Language | Mohawk, English |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Citizenship | Mohawk Nation / British subject |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Notable works | The White Wampum, Canadian Born, Flint and Feather |

Johnson—whose poetry was published in Canada, the United States, and Great Britain—was among a generation of widely-read writers who began to define Canadian literature. She was a key figure in the construction of the field as an institution and has made an indelible mark on Indigenous women's writing and performance as a whole.

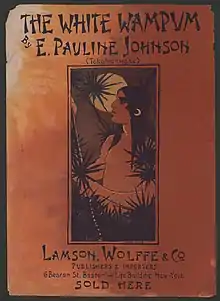

Johnson was notable for her poems, short stories, and performances that celebrated her mixed-race heritage, drawing from both Indigenous and English influences. She is most known for her books of poetry The White Wampum (1895), Canadian Born (1903), and Flint and Feather (1912); and her collections of stories Legends of Vancouver (1911), The Shagganappi (1913), and The Moccasin Maker (1913). While her literary reputation declined after her death, since the late 20th century there has been a renewed interest in her life and works. In 2002, a complete collection of her known poetry was published, entitled E. Pauline Johnson, Tekahionwake: Collected Poems and Selected Prose.

Due to the blending of her two cultures in her works, and her criticisms of the Canadian government, she was also a part of the New Woman feminist movement.

Family history

The Mohawk ancestors of Johnson's father, Chief George Henry Martin Johnson, had historically lived in what became the state of New York, United States . Theirs was the easternmost territory in the homelands of the Five Nations of the Iroquois League (later the Six Nations), also known as the Haudenosaunee. In 1758, her great-grandfather Tekahionwake was born in the province of New York. When he was baptized, he took the name Jacob Johnson. He was named after Sir William Johnson, the influential British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, who acted as his godfather.[3] The Johnson surname was subsequently passed down in the family.

After the American Revolutionary War started, Loyalists in the Mohawk Valley came under intense pressure. The Mohawk and three other Iroquois tribes had allied with the British rather than the rebel colonists. Jacob Johnson and his family moved to Canada. After the war they settled permanently in Ontario on land given by the Crown in partial compensation for Haudenosaunee losses of territory in New York.

His son John Smoke Johnson spoke English and Mohawk fluently and had a talent for oration. Due to his demonstrated patriotism to the Crown during the War of 1812, Smoke Johnson was made a Pine Tree Chief at the request of the British government. Although his title could not be inherited, his wife Helen Martin was a descendant of the Wolf Clan and a founding family of the Six Nations reserve.[4][5] Through her lineage and influence (as the Mohawk had a matrilineal kinship system), their son George Johnson was named chief.

George Johnson inherited his father's gift for languages and began his career as an Anglican Church missionary translator on the Six Nations reserve. Whilst working with the Anglican missionary assigned there, Johnson met the man's sister-in-law, Emily Howells.

Emily Howells was born in Bristol, England, to a well-established British family who had immigrated to the United States in 1832. Her father Henry Howells was a Quaker and intended to join the American abolitionist movement. Emily's mother Mary Best Howells died when the girl was five, when they were still in England. Her widowed father married again before they left for the US. In the US, he moved his family to several American cities, where he founded schools to gain an income, before settling in Eaglewood, New Jersey. After his second wife died (women had a high mortality in childbirth), Howells married a third time; he fathered a total of 24 children. He opposed slavery and encouraged his children to "pray for the blacks and to pity the poor Indians". His compassion did not preclude his believing that his own race was superior to others.

At the age of 21, Emily Howells moved to the Six Nations reserve in Ontario, Canada, to join her older sister, who had moved there with her Anglican missionary husband. Emily helped her sister care for her growing family. After falling in love with George Johnson, Howells gained a better understanding of the Native peoples and some perspective on her father's beliefs.

Much to the chagrin and displeasure of both their families, Johnson and Howells married in 1853. The birth of their first child reconciled the rift between their respective families. Several prominent Canadian families were descended from 18th- and 19th-century marriages between British fur traders, who had capital and social standing, and elite daughters of First Nations chiefs, in what were considered valuable economic and social alliances by both sides. Shortly after their marriage George became a chief of the Six Nations and was appointed as Crown interpreter for the Six Nations.[6] In 1856 Johnson built Chiefswood, a wood mansion at his 225-acre estate. He and his family lived here for years at the Six Nations reserve outside Brantford, Ontario.

In his roles as government interpreter and hereditary chief, George Johnson developed a reputation as a talented mediator between Native and European interests. He was well respected in Ontario. He also made enemies because of his efforts to stop illegal trading of reserve timber. Physically attacked by Native and non-Native men involved in this and liquor traffic, Johnson suffered from severe health problems; he died of a fever in 1884.[7]

Personal life

Early life

E. Pauline Johnson was born at her family home Chiefswood at the Six Nations reserve outside Brantford, Ontario. She was the youngest of four children of Emily Susanna Howells Johnson (1824–1898), an English immigrant, and George Henry Martin Johnson (1816–1884), a Mohawk hereditary clan chief. Because George Johnson worked as an interpreter and cultural negotiator among the Mohawk, British, and representatives of the government of Canada, the Johnsons were seen as part of Canadian high society. They were visited by distinguished intellectual and political guests of the time, including The Marquess of Lorne, Princess Louise, Prince Arthur, inventor Alexander Graham Bell, painter Homer Watson, anthropologist Horatio Hale, and the third Governor General of Canada, Lord Dufferin.[8]

Johnson's mother emphasized refinement and decorum in raising her children, cultivating an "aloof dignity" that she felt would earn them respect in their adulthood. Pauline Johnson's elegant manners and aristocratic air owed much to this background and training. George Johnson encouraged their four children to respect and learn about both their Mohawk and English heritage. Because George Johnson had partial Mohawk ancestry, his children were, by British law, legally considered Mohawk and wards of the British Crown. But, according to the Mohawk matrilineal kinship system, children are considered born into the mother's family, and take their status from her. Thus the Johnson children were considered to belong to no Mohawk family or clan, and were excluded from important aspects of the tribe's matrilineal culture.[9]

Early education

A sickly child, Johnson did not attend Brantford's Mohawk Institute, a residential school established in 1834. Her education was mostly at home and informal, derived from her mother, a series of non-Native governesses, a few years at the small school on the reserve, and self-guided reading in her family's expansive library. She read deeply in the works of Byron, Tennyson, Keats, Browning and Milton, and enjoyed reading tales about Indigenous people such as Longfellow's epic poem The Song of Hiawatha and John Richardson's Wacousta. These informed her own literary and theatrical work.[10]

Despite growing up in a time when racism against Indigenous people was normalized and common, Johnson and her siblings were encouraged to appreciate their Mohawk ancestry and culture. Her paternal grandfather John Smoke Johnson was a respected authority figure for her and her siblings. He educated them by traditional Indigenous oral storytelling before his death in 1886.[9] Johnson taught his life lessons and stories in Mohawk; the children understood it but were not fluent in speaking it.[8] Smoke Johnson's dramatic talents as a storyteller were absorbed by Pauline, who became known for her talent for elocution and her stage performances. She wore artifacts passed onto her by her Mohawk grandparents, such as a bear claw necklace, wampum belts, and various masks. Later in her life, Pauline Johnson expressed regret for not learning more of her grandfather's Mohawk heritage and language.[11]

At the age of 14, Johnson went to Brantford Central Collegiate with her brother Allen. She graduated in 1877. A fellow schoolmate was Sara Jeannette Duncan, who eventually developed her own journalistic and literary career.

Romantic life

Pauline Johnson attracted many potential suitors, and her sister recalled more than half a dozen marriage proposals from Euro-Canadians in her lifetime. Though the number of official romantic interests remains unknown, two later romances were identified as Charles R. L. Drayton in 1890 and Charles Wuerz in 1900.[12] But, Johnson never married nor remained in relationships for very long. She was said to have flirted with boys in Grand River. Later she wrote what was described as "intensely erotic poetry." Due to her career, she was unwilling to set aside her racial heritage to placate partners or in-laws, and adapt as a settler matron.[12] Despite everything, Johnson consistently had a strong network of supportive female friends and attested to the importance they had in her life.

Johnson said:

Women are fonder of me than men are. I have had none fail me, and I hope I have failed none. It is a keen pleasure for me to meet a congenial woman, one that I feel will understand me, and will in turn let me peep into her own life- having confidence in me, that is one of the dearest things between friends, strangers, acquaintances, or kindred.[12]

Stage career

During the 1880s, Johnson wrote and performed in amateur theatre productions. She enjoyed the Canadian outdoors, where she travelled by canoe. Shortly after her father's death in 1884, the family rented out Chiefswood. Johnson moved with her widowed mother and sister to a modest home in Brantford. She worked to support them all, and found that her stage performances enabled her to make a living. Johnson supported her mother until her death in 1898.[5]

The Young Men's Liberal Association invited Johnson to a Canadian authors evening in 1892 at the Toronto Art School Gallery. The only woman at the event, she read to an overflow crowd, along with luminaries such as William Douw Lighthall, William Wilfred Campbell, and Duncan Campbell Scott. "The poise and grace of this beautiful young woman standing before them captivated the audience even before she began to recite—not read, as the others had done"—her "Cry from an Indian Wife". She was the only author to be called back for an encore. "She had scored a personal triumph and saved the evening from turning into a disaster."[13] The success of this performance began the poet's 15-year stage career.

Johnson was signed up by Frank Yeigh, who had organized the Liberal event. He gave her the headline for her first show on 19 February 1892, where she made her debut with a new poem written for the event, "The Song My Paddle Sings".

Although she was already 31 years old, Johnson was perceived as a young and exotic Native beauty.[12] After her first recital season, she decided to emphasize the Native aspects of her public persona in her theatrical performances. Johnson created a two-part act that would confound the dichotomy of her European and Indigenous background. In act one, Johnson would come out as Tekahionwake, the Mohawk name of her great-grandfather, wearing a costume that served as a pastiche and assemblage of generic "Indian" objects that did not belong to one individual nation. But, her costume from 1892 to 1895 included items she had received from Mohawk and other sources, such as scalps inherited from her grandfather that hung from her wampum belt, spiritual masks, and other paraphernalia.[14] During this act she would recite dramatic "Indian" lyrics.

At intermission, she changed into fashionable English dress. In act two she came out as a pro North West Mountain Police (now known as the RCMP) Victorian English woman to recite her "English" verse.[13] Many of the items on her native dress were sold to museums such as the Ontario Provincial Museum, or to collectors such as the prominent American George Gustav Heye.[15] Upon her death she willed her "Indian" costume to the Museum of Vancouver.

There are many interpretations of Johnson's performances. The artist is quoted saying "I may act till the world grows wild and tense". Her shows were tremendously popular. She toured all across North America with her friend and fellow performer, and later business manager, Walter MacRaye. Her popularity was part of the immense interest by European Americans and Europeans in Indigenous peoples throughout the 19th century; the 1890s were also the period of popularity of Buffalo Bill's Wild West show and ethnological aboriginal exhibits.[12]

Literary career

In 1883 Johnson published her first full-length poem, "My Little Jean", in the New York Gems of Poetry. She began to increase the pace of her writing and publishing afterwards.

In 1885, poet Charles G. D. Roberts published Johnson's "A Cry from an Indian Wife" in The Week, Goldwin Smith's Toronto magazine. She based it on events of the battle of Cut Knife Creek during the Riel Rebellion. Roberts and Johnson became lifelong friends.[16] Johnson promoted her identity as a Mohawk, but as an adult spent little time with people of that culture.[5] In 1885, Johnson travelled to Buffalo, New York, to attend a ceremony honouring the Haudenosaunee leader Sagoyewatha, also known as Red Jacket. She wrote a poem expressing admiration for him and a plea for reconciliation between British and Native peoples.[8]

In 1886, Johnson was commissioned to write a poem to mark the unveiling in Brantford of a statue honouring Joseph Brant, the important Mohawk leader who was allied with the British during and after the American Revolutionary War. Her "Ode to Brant" was read at a 13 October ceremony before "the largest crowd the little city had ever seen".[13] It called for brotherhood between Native and white Canadians under British imperial authority.[8] The poem sparked a long article in the Toronto Globe, and increased interest in Johnson's poetry and heritage. The Brantford businessman William Foster Cockshutt read the poem at the ceremony, as Johnson was reportedly too shy.[16][13]

During the 1880s, Johnson built her reputation as a Canadian writer, regularly publishing in periodicals such as Globe, The Week, and Saturday Night. In the late 1880s and early 1890s, she published nearly every month, mostly in Saturday Night. Johnson is considered among a group of Canadian authors who were contributing to a distinct national literature.[17][14] The inclusion of two of her poems in W. D. Lighthall's anthology, Songs of the Great Dominion (1889), signalled her recognition.[12] Theodore Watts-Dunton noted her for praise in his review of the book; he quoted her entire poem "In the Shadows" and called her "the most interesting poetess now living". In her early works, Johnson wrote mostly about Canadian life, landscapes, and love in a post-Romantic mode, reflective of literary interests shared with her mother, rather than her Mohawk heritage.[12]

After retiring from the stage in August 1909, Johnson moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, where she continued writing. Her pieces included a series of articles for the Daily Province, based on stories related by her friend Chief Joe Capilano of the Squamish people of North Vancouver. In 1911, to help support Johnson, who was ill and poor, a group of friends organized the publication of these stories under the title Legends of Vancouver. They remain classics of that city's literature.

One of the stories was a Squamish legend of shape shifting: how a man was transformed into Siwash Rock "as an indestructible monument to Clean Fatherhood".[18] In another, Johnson told the history of Deadman's Island, a small islet off Stanley Park. In a poem in the collection, she named one of her favourite areas "Lost Lagoon", as the inlet seemed to disappear when the water emptied at low tide. The body of water has since been transformed into a permanent, fresh-water lake at Stanley Park, but it is still called Lost Lagoon.

Johnson drew on her mixed ethnic background and cultural heritages as a major theme in her work. The heroine of her short story "The De Lisle Affair" (1897), was disguised. Readers were discomforted due to the uncertainty of appearances, particularly amongst women.[12] Due to their subordinated social, economic, and political positions, women often had to play the roles as mediators for men, practising ambiguity and disloyalty for the sake of their safety and sanctity. The notion of shifting identity is seen in "The Ballad of Yaada" (1913), where a female character explains "not to friend – but unto foeman I belong ... though you hate, / I still must love him," which suggests the potential for communities to understand one another through love and kindness.[12] But she also explores the risk of the coming together of communities and cultures. Johnson's mixed-race heroine Esther, in "As It Was in the Beginning", kills her unfaithful White lover. With the words "I am a Redskin, but I am something else, too – I am a woman", Esther is demanding recognition of multiple subjectivities. Johnson was trying to convey that the real world consists of much more than oppressive ideologies and artificial divisions of race and nation enforced by authoritative figures such as the racist Protestant minister in this story, revealingly nicknamed "St Paul" after the biblical misogynist.[12]

The posthumous Shagganappi (1913) and The Moccasin Maker (1913) are collections of selected stories first published in periodicals. Johnson wrote on a variety of sentimental, didactic, and biographical topics. Veronica Strong-Boag and Carole Gerson provided a provisional chronological list of Johnson's writings in their book Paddling Her Own Canoe: The Times and Texts of E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) (2000).

Death

Johnson died of breast cancer on 7 March 1913 in Vancouver, British Columbia. Devotion to her persisted after her death. Her funeral was held on what would have been her 52nd birthday. It was the largest public funeral in Vancouver history to that time. The city closed its offices and flew flags at half-mast; a memorial service was held in Vancouver's most prestigious church, the Anglican cathedral supervised by the Women's Canadian Club. Squamish people also lined the streets and followed her funeral cortege on 10 March 1913. The Vancouver Province headline on the day of her funeral said, "Canada's poetess is laid to rest". Smaller memorial services were also held in Brantford, Ontario, organized by Euro-Canadian admirers.

Johnson's ashes were placed in Stanley Park near Siwash Rock, through the special intervention of the governor general, the Duke of Connaught, who had visited during her final illness, and Sam Hughes, the minister of militia.

Her will was prepared by the prestigious firm of Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper, son of the former 6th prime minister of Canada. Despite Johnson's preference for an unmarked grave, the Women's Canadian Club sought to raise money for a monument for her. In 1922, a cairn was erected at her burial site with the inscription stating, in part, "In memory of one whose life and writings were an uplift and a blessing to our nation".[16] During World War One, part of the royalties from Legends of Vancouver went to purchase a machine gun inscribed "Tekahionwake" for the 29th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Johnson left a mark on Canadian history that has carried on long after her death.

Reception

Past

Living in a world that judged Indigenous people and women harshly, Johnson had to draw upon all the resources available to her in order to work out a then problematic professional life without threatening the public. Writer Arthur Stringer wrote that she had considerable talent for disguise; during a conversation between the two of them in a modest hotel room, she tended to her ironing. He wrote, "She was not quite as primitive as she pretended. Or, to put it more charitably, she was not as elemental as her audiences liked to think her. She was, in one way, quite patrician in mind and spirit." Class was an essential part of her repertoire; by clinging to its privileges Johnson was able to counteract other disadvantages.

Two of Johnson's poems were included in W. D. Lighthall's 1889 anthology Songs of the Great Dominion. This resulted in her recognition as a poet helping create Canada's new literary identity and signalled her inclusion in a group of significant Canadian English-language writers. The anthology had a section entitled "The Indian"; however, Johnson's poems were not placed there. Her canoeing poem, "In the Shadows", appears in the section "Sports and Free Life," and her poem about the Grand River, "At the Ferry", is in the "Places" section. To the casual Canadian reader, Johnson probably blended into the Anglo-centric mainstream of English-language Canadian literature. Yet this was not quite where Johnson situated herself. Her original selection of her "best" verse, which was "most Canadian in tone and color", included "A Cry from an Indian Wife" and "The Indian Death Cry" (1888), poems that she felt would interest Lighthall on account of her "nationality". Using this word to signal "Indian" rather than "Canadian", in her correspondence with the editor of the most noteworthy post-Confederation literary anthology, marks her unique self-placement within the country's emergent national literature.

Johnson's still tentative public identification with her Native roots was encouraged by English critic Theodore Watts-Dunton. His review of Songs of the Great Dominion, in the prestigious London journal The Athenaeum, drew from Lighthall's biographical notes to emphasize Johnson as "the cultivated daughter of an Indian chief, who is, on account of her descent, the most interesting English poetess now living". He quoted the entire text of "In the Shadows" in his review. The fascination of the imperial metropolis with the relatively exotic aspects of the former colony contributed substantially to Johnson's later self-dramatization to British audiences. There she downplayed her English mother in order to highlight her Mohawk father.

In such practical and highly symbolic ways, Pauline Johnson was simultaneously succoured and recognized, firmly integrated into a Euro-Canadian world view that conveniently interpreted the "noble Indian" as a figment of the national past. From such a perspective, the Squamish people who lined the streets and followed her funeral cortège on 10 March 1913 supplied no more than a romantic backdrop for the best-known Canadian Native woman of her era. To the end, Johnson's life was mediated and appropriated by White admirers and friends.

Present

Scholars have had difficulty identifying Johnson's complete works, as much was published in periodicals. Her first volume of poetry, The White Wampum, was published in London in 1895. It was followed by Canadian Born in 1903. The contents of these volumes, together with additional poems, were published as the collection Flint and Feather in 1912. Reprinted many times, this book has been one of the best-selling titles of Canadian poetry. Since the 1917 edition, Flint and Feather has been misleadingly subtitled The Complete Poems of E. Pauline Johnson.

But in 2002, professors Carole Gerson and Veronica Strong-Boag produced an edition, Tekahionwake: Collected Poems and Selected Prose, that contains all of Johnson's poems found up to that date. A number of biographers and literary critics have downplayed her literary contributions, as they contend that her performances contributed most to her literary reputation during her lifetime.[10][19] W. J. Keith wrote: "Pauline Johnson's life was more interesting than her writing ... with ambitions as a poet, she produced little or nothing of value in the eyes of critics who emphasize style rather than content."[20]

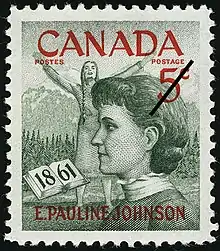

Despite the acclaim she received from contemporaries, Johnson had a decline in reputation in the decades after her death.[14] It was not until 1961, with commemoration of the centenary of her birth, that Johnson began to be recognized as an important Canadian cultural figure. This was also the beginning of a period when the writing of women and First Nations people began to be re-evaluated and recognized.

Canadian author Margaret Atwood admitted that she did not study literature by Native authors when preparing Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature (1972), her seminal work. At its publication, she had said she could not find Native works. She mused, "Why did I overlook Pauline Johnson? Perhaps because, being half-white, she somehow didn't rate as the real thing, even among Natives; although she is undergoing reclamation today." Atwood's comments indicated that Johnson's multicultural identity contributed to her neglect by critics.[21]

As Atwood noted, since the late 20th century, Johnson's writings and performance career have been reevaluated by literary, feminist, and postcolonial critics. They have appreciated her importance as a New Woman and a figure of resistance to dominant ideas about race, gender, Native Rights, and Canada.[12] The growth in literature written by First Nations people during the 1980s and 1990s has also prompted writers and scholars to investigate Native oral and written literary history, to which Johnson made a significant contribution.[12]

E. Pauline Johnson has received much less attention than one might expect for an accomplished and controversial literary figure. Older critics often dismissed Johnson's work; in 1988 critic Charles Lillard characterized her readers dismissively as "tourists, grandmothers ... and the curious".[12] In 1992, a Specialized Catalogue of Canadian Stamps, issued by Canada Post misrepresented Johnson as a "Mohawk Princess", ignoring her scholarly accomplishments. And in 1999 Patrick Watson introduced the History Channel's biography of Johnson by deprecating "The Song My Paddle Sings". Even in regard to scholarship, Johnson was often overlooked in the 1980s in favour of Duncan Campbell Scott for writing about indigenous life,a although he was Euro-Canadian.[12] But a new generation of feminist scholars has begun to counter narratives of Canadian literary history and Johnson is being recognised for her literary efforts.

An examination of the reception of Johnson's writing over the course of a century provides an opportunity to study changing notions of literary value, and the shifting demarcation between high and popular culture. During her lifetime, this line scarcely existed in Canada, where nationalism prevailed as the primary evaluative criterion. The Vancouver Province headline on the day of her funeral in March 1913 simply stated, "Canada's poetess is laid to rest".[12] During the following decade, an "elegiac quality often imbued references to Pauline Johnson".[12] To Euro-Canadians, she was considered the last spokesperson for a people destined to disappear: "The time must come for us to go down, and when it comes may we have the strength to meet our fate with such fortitude and silent dignity as did the Red Man his."[12]

Johnson is capable of remarkably clear dissections of the racist habits of the time, a clarity that comes out of her standpoint as a privileged Mohawk educated in both Haudenosaunee society and white Anglo-Canadian culture.[7] Her deft use of analogues between Iroquois traditions of government and religion and those of the dominant culture, works to show the Six Nations to be as politically responsible as, and far less sexist than, the British; the one God of the Longhouse to be more benign than the Christian God; and Iroquois traditions to be more time-tested, healthy, and virtuous than those of a corrupted urban modernity.[7] However, her patriotic enthusiasm for Canada and the Crown, as expressed in "Canadian Born" and elsewhere, seems at odds with her Indigenous advocacy.[7]

In the 21st century, some have questioned the moral ambiguity of Johnson's work and whether she herself was racist. In 2017 school administrators at the High Park Alternative Public School in Toronto characterized the song "Land of the Silver Birch" as racist, mistakenly asserting that Johnson wrote the poem on which the song is based. In a letter to parents, they said, "While its lyrics are not overtly racist ... the historical context of the song is racist." Some experts disagreed with this assertion, and the music teacher, who arranged for the song to be performed at a school concert, sued the administration for defamation.[22]

Legacy

New Woman

While Johnson remained passionate and committed to Native causes, she was deeply entrenched in the world of Canada's pioneering New Women and their efforts to enlarge opportunities for the female sex. Amid a post-Confederation generation of middle-class white women, Johnson paved a way and made a name for herself as an Indigenous woman. Johnson's mother, who was English, notably avoided public life and "the glare of the fierce light that beat upon prominent lives, the unrest of fame, and the disquiet of public careers".[12] Johnson by contrast pursued public life in her effort to support her family; she made her way as a New Woman in North America and Britain.

Throughout her teens Johnson was an amateur performer and enthusiastic writer. She resisted her mother's opposition to a stage career and purposely took advantage of all opportunities that would lead her into the spotlight.[12] Johnson's sister Evelyn recalled her response to a query about accepting Frank Yeigh's initial invitation to the prestigious 1892 Canadian literature evening in Toronto: "You bet. Oh Ev, it will be such a help to get before the profession."[12]

After gaining an encore at her first performance, Johnson was well on her way in taking a place amongst a community of New Women. They were seen to puzzle and disturb their contemporaries, while advancing the frontiers of activity deemed respectable for women of that time.[12] Despite her connections to Mohawk and other Indigenous communities, Johnson was a partially European woman who understood Anglo-Imperial values; she blended those amongst her bohemian aspirations to advance her career and make an adequate living as an artist.[12] Johnson presents a striking example of the turn-of-the-century New Woman in her successful forging of an independent literary and performing career.[12]

Johnson had to maintain dual loyalties for causes that were not overlapping in her time, although the "overwhelmingly White and middle-class woman's movement" shared some issue with First Nations peoples, and some members attempted to make amends and right racist wrongs.[12] Feminist and Aboriginal protests regularly disturbed the decades after Confederation; both groups rallied for the Dominion to make education, economic opportunity, and political equality available to more than white men. Both groups were denigrated by doctors, politicians, churchmen, and anthropologists, yet advocates for each group rarely communicated.[12] Women suffragists were distanced from First Nations people by racism, and acceptance of the privilege they received as whites. They generally refused to accept First Nations peoples as equals. Because of this, Johnson was in a unique position to rally and advocate for both sides, whilst attempting to encourage communication amongst the two. This differentiated her from many activists of her time and is evident in the texts she produced.[12]

Canadian literature

A 1997 survey by Hartmut Lutz of the state of Canadian Native Literature in the 1960s, pointed to the importance of this era as establishing the foundation for the new wave of Indigenous writing that surged in the 1980s and 1990s. Lutz identified "1967 as the beginning of contemporary writing by Native authors in Canada", marking the publication of George Clutesi's landmark work, Son of Raven, Son of Deer.[12] His discussion briefly mentioned Johnson but he did not acknowledge that 1961 marked the centennial of Johnson's birth; the resulting celebration nationally demonstrated the endurance of her prominence in Indigenous and Canadian literature and popular culture.[12]

As a writer and performer, Johnson was a central figure in literary and performance history of Indigenous women in Canada. Of her importance, Mohawk writer Beth Brant wrote "Pauline Johnson's physical body died in 1913, but her spirit still communicates to us who are Native women writers. She walked the writing path clearing the brush for us to follow."[12]

Johnson influence over other female Indigenous Canadian writers was expressed by their references to her throughout various decades, for example:

- 1989 - Poet Joan Crate (Metis) referred to Johnson in the title of her book of poetry Pale as Real Ladies: Poems for Pauline Johnson.

- 2000 - Jeannette Armstrong (Okanagan) opened her novel Whispering in Shadows with Johnson's poem "Moonset".

- 2002 - Poet Janet Rogers (Mohawk) published her play Pauline and Emily, Two Women, recasting Johnson as a friend and interlocutor of Canadian artist Emily Carr, who often painted Indigenous life as decayed and dying.

- 1993 - Shelley Niro (Mohawk) made a film, It Starts With a Whisper, that includes a reading of Johnson's "The Song My Paddle Sings".[7]

Broadcaster Rosanna Deerchild (Cree) remembers stumbling across "The Cattle Thief" in the public library: "I hand-copied that entire poem right then and there and carried it around with me, reading it over and over." Later she wrote a poem about Johnson entitled "she writes us alive." There are numerous other examples of contemporary Indigenous artists, women and men alike, who were inspired by Johnson, notably within Canadian literature.[7]

Canadian government

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, government policies towards Indigenous Canadians were increasingly cruel. Across the continent, Indigenous children were forcibly removed to residential schools; on the Prairies, communities such as the Dogrib, Cree and Blackfoot were confined to artificial reserves; settler attitudes towards the Dominion's original inhabitants curdled and hardened. Johnson critiqued some Canadian policies that resulted in such legalized and justified mistreatment of Indigenous peoples. For example, in her poem "A Cry From an Indian Wife", the final verse reads:

Go forth, nor bend to greed of white men's hands,

By right, by birth we Indians own these lands,

Though starved, crushed, plundered, lies our nation low ...

Perhaps the white man's God has willed it so.[23]

Because of the Indian Act and faulty scientific blood quantum racial determinism, Johnson was often belittled by the term "halfbreed".[24][25]

Posthumous honours

- 1922: A monument was erected to Johnson at Stanley Park in the city of Vancouver, BC.

- 1945: Johnson was designated a Person of National Historic Significance.[4][26]

- 1953: Chiefswood, Johnson's childhood home, constructed in 1856 in Brantford, was listed as a National Historic Site, based on both her and her father's historical significance. It has been preserved as a house museum and is the oldest Indigenous mansion surviving from before Confederation.[27]

- 1961: On the centennial of her birth, Johnson was celebrated with a commemorative stamp bearing her image; she was "the first woman (other than the Queen), the first author, and the first aboriginal Canadian to thus be honored."[14]

- 1967—: Elementary schools were named in her honour in West Vancouver, British Columbia; Scarborough, Ontario; Hamilton, Ontario; and Burlington, Ontario, and a high school, Pauline Johnson Collegiate & Vocational School in Brantford.

- 2004: An Ontario Historical Plaque was erected in front of the Chiefswood house museum by the province to commemorate Johnson's role in the region's heritage.[28]

- 2010: Canadian actor Donald Sutherland read the following quote from her poem "Autumn's Orchestra", at the opening ceremonies of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver:

Know by the thread of music woven through

This fragile web of cadences I spin,

That I have only caught these songs since you

Voiced them upon your haunting violin.

- 2010: Composer Jeff Enns was commissioned to create a song based on Johnson's poem "At Sunset". His work was sung and recorded by the Canadian Chamber Choir under the artistic direction of Julia Davids.[29][30]

- 2014: The City Opera of Vancouver commissioned Pauline, a chamber opera dealing with her life, multicultural identity, and art. The composer is Tobin Stokes, and the libretto was written by Margaret Atwood, both Canadian. The work premiered on 23 May 2014, at the York Theatre in Vancouver. The first opera to be written about Johnson, it is set in the last week of her life.[31]

- 2016: Johnson was one of five finalists of significant women to be featured on Canadian banknotes; Viola Desmond won the contest.[32]

Complete literary works

Dated publications

This list cites the first known publication of individual texts, as well as first appearance in one of Johnson's books, based on the work of Veronica Jane Strong-Boag and Carole Gerson.[12]

- 1883

- Gems of Poetry

- "My Little Jean"

- Gems of Poetry

- 1884

- Gems of Poetry

- "The Rift. By Margaret Rox"

- "Rover"

- Transactions of the Buffalo Historic Society

- "The Re-interment of Red Jacket"

- Gems of Poetry

- 1885

- Gems of Poetry

- "Iris to Floretta"

- "The Sea Queen"

- The Week

- "The Sea Queen"

- "A Cry from an Indian Wife"

- "In the Shadows"

- Gems of Poetry

- 1886

- Souvenir pamphlet

- "'Brant', A Memorial Ode"

- The Week

- "The Firs"

- "Easter Lilies"

- "At the Ferry"

- "A Request"

- Souvenir pamphlet

- 1887

- Musical Journal

- "Life"

- The Week

- "The Vigil of St Basil" retitled "Fasting"

- Musical Journal

- 1888

- Saturday Night

- "My English Letter"

- "Easter, 1888"

- "Unguessed"

- "The Death-Cry"

- "Keepsakes"

- "The Flight of the Crows"

- "Under Canvas"

- "Workworn"

- "A Backwoods Christmas" retitled "The Lumberman's Christmas"

- The Week

- "Joe" retitled "Joe: An Etching"

- "Our Brotherhood"

- Saturday Night

- 1889

- Globe

- "Evergreens"

- Saturday Night

- "The Happy Hunting Grounds"

- "Close By"

- "Ungranted" retitled "Overlooked"

- "Old Erie" retitled "Erie Waters"

- "Shadow River"

- "Bass Lake (Muskoka)"

- "Temptation"

- "Fortune's Favors"

- "Rondeau"

- "Christmastide"

- The Week

- "Nocturne"

- Globe

- 1890

- Brantford Courier

- "Charming Word Pictures. Etchings by an Idler of Muskoka and the Beautiful North"

- "Charming Word Pictures. Etchings by a Muskoka Idler"

- "Charming Word Pictures. Etchings by a Muskoka Idler"

- Saturday Night

- "We Three" retitled "Beyond the Blue"

- "In April"

- "For Queen and Country"

- "Back Number [Chief of the Six Nations]"

- "The Idlers"

- "With Paddle and Peterboro"

- "Depths"

- "Day Dawn"

- "'Held by the Enemy'"

- "With Canvas Overhead"

- "Two Women"

- "A Day's Frog Fishing"

- "In October" retitled "October in Canada"

- "Thro' Time and Bitter Distance" retitled "Through Time and Bitter Distance"

- "As Red Men Die"

- Brantford Courier

- 1891

- Brantford Expositor

- "A'bram"

- Dominion Illustrated

- "Our Iroquois Compatriots"

- Independent

- "Re-Voyage"

- "At Husking Time"

- Outing

- "The Camper"

- "Ripples and Paddle Plashes: A Canoe Story"

- Saturday Night

- "The Last Page"

- "The Showshoer"

- "Outlooking"

- "The Seventh Day"

- "The Vagabonds"

- "Prone on the Earth"

- "In Days to Come"

- "Striking Camp"

- "The Pilot of the Plains"

- Weekly Detroit Free Press

- "Canoeing"

- Young Canadian

- "Star Lake"

- Brantford Expositor

- 1892

- Belford's Magazine

- "Wave-Won"

- Brantford Expositor

- "Forty-Five Miles on the Grand"

- Dominion Illustrated

- "Indian Medicine Men and their Magic"

- Lake Magazine

- "Penseroso"

- Outing

- "Outdoor Pastimes for Women"

- Saturday Night

- "A Story of a Boy and a Dog"

- "Rondeau. The Skater"

- "Glimpse at the Grand River Indians"

- "The Song My Paddle Sings"

- "At Sunset"

- "Rainfall"

- "Sail and Paddle"

- "The Avenger"

- Sunday Globe

- "A Strong Race Opinion: on the Indian Girl in Modern Fiction"

- Weekly Detroit Free Press

- "On Wings of Steel"

- "A Brother Chief"

- "The Game of Lacrosse"

- "Reckless Young Canada"

- Belford's Magazine

- 1893

- American Canoe Club Yearbook

- "The Portage"

- Canadian Magazine

- "The Birds' Lullaby"

- Dominion Illustrated

- "A Red Girl's Reasoning" retitled "A Sweet Wild Flower"

- Illustrated Buffalo Express

- "Sail and Paddle. The Annual Meeting of the Canoe Association"

- Outing

- "Outdoor Pastimes for Women", columns in the Monthly Record

- "A Week in the 'Wild Cat'"

- Saturday Night

- "The Mariner"

- "Brier"

- "Canoe and Canvas"

- "Princes of the Paddle"

- "Wolverine"

- Weekly Detroit Free Press

- "The Song My Paddle Sings", retitled "Canoeing in Canada"

- American Canoe Club Yearbook

- 1894

- Acta Victoriana

- "In Freshet Time"

- Art Calendar, illustrated by Robert Holmes

- "Thistledown"

- Globe

- "There and Back, by Miss Poetry (E. Pauline Johnson), and Mr Prose (Owen A. Smily)", 15 December, 3–4.

- Harper's Weekly

- "The Iroquois of the Grand River"

- Ladies' Journal

- "In Gray Days"

- Outing

- "Moon-Set"

- The Varsity

- "Marsh-Lands"

- The Week

- "The Cattle Thief"

- Acta Victoriana

- 1895

- Black and White

- "The Lifting of the Mist"

- Brantford Expositor

- "The Six Nations"

- Globe

- "The Races in Prose and Verse, by Miss Poetry and Mr Prose"

- Halifax Herald

- "Iroquois Women of Canada"

- Our Animal Friends

- "From the Country of the Cree"

- The Rudder

- "Sou'wester"

- "Canoe and Canvas. I"

- "Canoe and Canvas. II"

- "Canoe and Canvas. Ill"

- "Canoe and Canvas. IV"

- "Becalmed"

- The Year Book

- "The White and the Green"

- The White Wampum

- Previous publication unknown: "Dawendine", "Ojistoh"

- Black and White

- 1896

- Black and White

- "Low Tide at St Andrews"

- "The Quill Worker"

- Daily Mail and Empire

- "The Good Old N.P."

- Harper's Weekly

- "Lullaby of the Iroquois"

- "The Corn Husker"

- Massey's Magazine

- "The Singer of Tantramar"

- "The Songster"

- "The Derelict"

- Our Animal Friends

- "A Glimpse of the Prairie Wolf"

- The Rudder

- "With Barry in the Bow. Act I. Scene: The Land of Evangeline"

- "With Barry in the Bow. Act II. Scene: The Great North Land"

- "With Barry in the Bow. Interlude between Acts II and III"

- "The American Canoe Association at Grindstone Island"

- Black and White

- 1897

- Ludgate Magazine

- "Gambling among the Iroquois"

- Massey's Magazine

- "The Indian Corn Planter"

- Our Animal Friends

- "In Gopher-Land"

- The Rudder

- "With Barry in the Bow. Act III. Scene: The Land of the Setting Sun"

- "With Barry in the Bow. Act IV"

- "With Barry in the Bow. Act V"

- Saturday Night

- "The De Lisle Affair"

- Ludgate Magazine

- 1898

- Canada

- "Organization of the Iroquois"

- Town Topics

- "The Indian Legend of Qu'Appelle Valley", retitled "The Legend of Qu'Appelle Valley"

- Canada

- 1899

- Free Press Home Journal (Winnipeg)

- "'Give Us Barabbas'"

- Globe

- "H.M.S."

- Saturday Night

- "As It Was in the Beginning"

- Town Topics

- "Some People I Have Met"

- Free Press Home Journal (Winnipeg)

- 1900

- Halifax Herald

- "Canadian Born"

- Halifax Herald

- 1901

- "His Majesty the King"

- 1902

- Evening News

- "Letter to the Editor" (about Wacousta)

- "Our Sister of the Seas"

- "Among the Blackfoots"

- Smart Set

- "The Prodigal"

- Evening News

- 1903

- Canadian Born

- Previous publication unknown: "The Art of Alma-Tadema", "At Half-Mast", "The City and The Sea", "Golden – Of the Selkirks", "Good-Bye", "Guard of the Eastern Gate", "Lady Icicle", "Lady Lorgnette", "Prairie Greyhounds", "The Riders of the Plains" [performed 1899], "The Sleeping Giant", "A Toast", "Your Mirror Frame".

- Saturday Night

- "Made in Canada"

- Canadian Born

- 1904

- Rod and Gun

- "The Train Dogs"

- Rod and Gun

- 1906

- Black and White

- "When George Was King"

- Boys' World

- "Maurice of His Majesty's Mails"

- "The Saucy Seven"

- "Dick Dines with his 'Dad'"

- Daily Express (London)

- "A Pagan in St. Paul's", retitled "A Pagan in St. Paul's Cathedral"

- "The Lodge of the Law Makers"

- "The Silent News Carriers"

- "Sons of Savages"

- Over-Seas

- "The Traffic of the Trail"

- "Newfoundland"

- Saturday Night

- "The Cariboo Trail"

- Standard (Montreal)

- "Chance of Newfoundland Joining Canada Switches Interest to Britain's Oldest Colony"

- Black and White

- 1907

- Boys' World

- "We-eho's Sacrifice", retitled "We-hro's Sacrifice"

- "Gun-shy Billy"

- "The Broken String"

- "Little Wolf-Willow"

- "The Shadow Trail"

- Calgary Daily News

- "The Man in Chrysanthemum Land"

- Canada (London)

- "Longboat of the Onondagas"

- Canadian Magazine

- "The Cattle Country", retitled "The Foothill Country"

- "The Haunting Thaw"

- "The Trail to Lillooet"

- Mother's Magazine

- "The Little Red Indian's Day"

- "Her Dominion – A Story of 1867, and Canada's Confederation"

- "The Home Comers"

- "The Prayers of the Pagan"

- Boys' World

- 1908

- Boys' World

- "A Night With 'North Eagle'"

- "The Tribe of Tom Longboat"

- "The Lieutenant Governor's Prize"

- "Canada's Lacrosse"

- "The Scarlet Eye"

- "The Cruise of the 'Brown Owl'"

- Brantford Daily Expositor

- "Canada"

- Mother's Magazine

- "Mothers of a Great Red Race"

- "Winter Indoor Life of the Indian Mother and Child"

- "How One Resourceful Mother Planned an Inexpensive Outing"

- "Outdoor Occupations of the Indian Mother and her Children", Heroic Indian Mothers

- "Mother of the Motherless"

- Saturday Night

- "The Foothill Country", previously "The Cattle Country"

- "The Southward Trail"

- When George Was King, and Other Poems

- "Autumn's Orchestra"

- Boys' World

- 1909

- Boys' World

- "The Broken Barrels I"

- "The Broken Barrels II"

- "The Whistling Swans"

- "The Delaware Idol"

- "The King's Coin (Chapter One)"

- "The King's Coin (Chapter Two)"

- "The King's Coin (Chapter Three)"

- "The King's Coin (Chapter Four)"

- "The King's Coin (Chapter Five)"

- "Jack O' Lantern I"

- "Jack O' Lantern II"

- Mother's Magazine

- "The Legend of the Two Sisters", as "The True Legend of Vancouver Lions", Daily Province Magazine, 16 April 1910; retitled "The Two Sisters"

- "Mother o' the Men"

- "The Envoy Extraordinary"

- "My Mother"

- "The Christmas Heart"

- Saturday Night

- "The Chinook Wind"

- Boys' World

- 1910

- Boys' World

- "The Brotherhood"

- "The Wolf-Brothers"

- "The Silver Craft of the Mohawks: The Protective Totem"

- "The Silver Craft of the Mohawks: The Brooch of Brotherhood"

- "The Silver Craft of the Mohawks: The Hunter's Heart"

- "The Signal Code"

- "England's Sailor King"

- "The Barnardo Boy"

- "A Chieftain Prince"

- "The Potlatch"

- "The Story of the First Telephone"

- "The Silver Craft of the Mohawks: The Traitor's Hearts"

- "The Silver Craft of the Mohawks: The Sun of Friendship"

- "On My Honor"

- Canadian Magazine

- "The Homing Bee"

- Daily Province Magazine

- "The True Legend of Vancouver's Lions", retitled "The Two Sisters"

- "The Duke of Connaught as Chief of the Iroquois", retitled "A Royal Mohawk Chief"

- "A Legend of the Squamish", retitled "The Lost Island"

- "A True Legend of Siwash Rock: a Monument to Clean Fatherhood", retitled "The Siwash Rock"

- "The Recluse of the Capilano Canyon", retitled "The Recluse"

- "A Legend of Deer Lake", retitled "Deer Lake"

- "The 'Lure' in Stanley Park"

- "The Deep Waters: A Rare Squamish Legend", retitled "The Great Deep Water: A Legend of 'The Flood'"

- Mother's Magazine, February 1912; retitled "The Deep Waters"

- "The Legend of the Lost Salmon Run", retitled "The Lost Salmon Run"

- "The Sea Serpent of Brockton Point", retitled "The Sea Serpent"

- "The Legend of the Seven White Swans"

- "The True Legend of Deadman's Island", retitled "Deadman's Island"

- "The Lost Lagoon"

- "A Squamish Legend of Napoleon"

- "The Orchard of Evangeline's Land"

- "The Call of the Old Qu' Appelle Valley"

- "Prairie and Foothill Animals That Despise the Southward Trail"

- "Where the Horse is King"

- "A Legend of Point Grey", retitled "Point Grey"

- "The Great Heights above the Tulameen", retitled "The Tulameen Trail"

- "Trails of the Old Tillicums"

- Mother's Magazine

- "The Nest Builder"

- "The Call of the Skookum Chuck"

- "From the Child's Viewpoint"

- "The Grey Archway: A Legend of the Charlotte Islands"

- "The Legend of the Squamish Twins", retitled "The Recluse of Capilano Canyon", retitled "The Recluse"

- "The Lost Salmon Run: A Legend of the Pacific Coast", retitled "The Legend of the Lost Salmon Run"

- Daily Province

- "The Lost Salmon Run"

- "The Legend of Siwash Rock"

- "Catharine of the 'Crow's Nest'"

- What to Do

- "A Lost Luncheon"

- "The Building Beaver"

- Boys' World

- 1911

- Legends of Vancouver

- Boys' World

- "The King Georgeman [I]"

- "The King Georgeman [II]"

- Daily Province Magazine

- "The Grey Archway: A Legend of the Coast", retitled "The Grey Archway"

- "The Great New Year White Dog: Sacrifice of the Onondagas"

- Daily Province

- "La Crosse"

- Mother's Magazine

- "Hoolool of the Totem Poles"

- "The Tenas Klootchman"

- "The Legend of the Seven Swans"

- "The Legend of the Ice Babies"

- 1912

- Flint and Feather

- Previous publication unknown: "The Archers", "Brandon", "The King's Consort"

- Mother's Magazine

- "The Legend of Lillooet Falls"

- "The Great Deep Water: A Legend of 'The Flood'"

- Sun (Vancouver)

- "The Unfailing Lamp"

- Flint and Feather

- 1913

- The Moccasin Maker

- "Her Majesty's Guest"

- The Shagganappi

- "The Shagganappi"

- Boys' World

- "The Little Red Messenger [I]"

- "The Little Red Messenger [II]"

- Calgary Herald

- "Calgary of the Plains"

- Canadian Magazine

- "Song"

- "In Heidleberg"

- "Aftermath"

- Saturday Night

- "The Ballad of Yaada"

- Pamphlet (Toronto: Musson)

- "And He Said, Fight On"

- The Moccasin Maker

- 1914

- Canadian Magazine

- "Reclaimed Lands"

- "Coaching on the Cariboo Trail"

- Daily Province

- "Coaching on the Cariboo Trail"

- Canadian Magazine

- 1916

- Flint and Feather

- "The Man from Chrysanthemum Land" (written for The Spectator)

- Flint and Feather

- 1929

- Town Hall Tonight by Walter McRaye

- "To Walter McRaye"

- Town Hall Tonight by Walter McRaye

- 1947

- Pauline Johnson and Her Friends by McRaye

- "The Ballad of Laloo"

- Pauline Johnson and Her Friends by McRaye

Poems in the Chiefswood Scrapbook: c. 1884–1924

- "Both Sides" New York Life, 1888

- "Comrades, we are serving" n.p., n.d.

- "Disillusioned" (second part "Both Sides") Judge, n.d.

- "Lent" signed Woeful Jack, n.p., n.d.

- "What the Soldier Said" Brant Churchman, n.d.

Clippings at McMaster University

- "In the Shadows. My Version. By the Pasha" n.p.

- "Traverse Bay" n.p.

- "Winnipeg – At Sunset" Free Press.

- "Interesting Description, by a Descendant of the Mohawks, of Tutela Heights, Ontario" Boston Evening Transcript.

Dated manuscripts

- 1876. ""The Fourth Act"

- 1878. "Think of Me"

- 1879. "My Jeanie"

- 1890. "Dear little girl from far / Beyond the seas"

- 1901. "Morrowland" dated Holy Saturday

- 1906. "Witchcraft and the Winner"

Undated manuscripts

- Early fragment, "alas how damning praise can be"

- Epigraph, "But all the poem was soul of me"

- "The Battleford Trail" c. 1902–1903

- "If Only I Could Know" (published as "In Days to Come")

- "The Mouse's Message"

- "'Old Maids' Children"

- "The Stings of Civilization"

- "Tillicum Talks"

- "To C.H.W."

- "The Tossing of a Rose"

Untraced writings

- "Canada for the Canadians" (1902)

- "On List of Tides" (c. 1908)

- "Britain's First Born C."

- "The Flying Sun"

- "God's Laughter"

- "Indian Church Workers"

- "The Missing Miss Orme"

- "The Rain"

- "The Silent Speakers"

Titles from concert programs and reviews

- "At the Ball" (1902–1903)

- "Beneath the British Flag" (1906)

- "The Captive" (1892)

- "A Case of Flirtation" (1899)

- "The Chief's Daughter" (1898)

- "The Convict's Wife" (1892)

- "Fashionable Intelligence" (1906)

- "The Englishman" (1902–1903)

- "Half Mast" (1897)

- "Her Majesty's Troops" (1900); "His Majesty's Troops" (1904)

- "His Sister's Son" (1895–1897)

- "Legend of the Lover's Leap" (1892)

- "Mrs Stewart's Five O'Clock Tea" (1894–1906)

- "My Girls" (1897)

- "People I Have Met" (1902)

- "A Plea for the Northwest" (1892–1893)

- "Redwing" (1892–1893)

- "Stepping Stones" (1897)

- "The Success of the Season" (1894–1906)

- "The White Wampum" (1896–1897)

References

- "Tekahionwake: an Indian Poetess in London," Pauline Johnson Archive: Tekahionwake. Archives and Research Collections, McMaster University. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- Rose, Marilyn J. [1998] 2003. “Johnson, Emily Pauline.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14. University of Toronto / Université Laval.

- Leighton, Douglas (1982). "Johnson, John." In Dictionary of Canadian Biography XI, edited by F. G. Halpenny. University of Toronto Press.

- Keller, Betty. 1981. Pauline: A Biography of Pauline, Halifax, NS: Formac Publishing. p. 4, cited by "Johnson Family Tree." Chiefswood National Historic Site. Accessed 27 May 2011.

- Lyon, George W. 1990. "Pauline Johnson: A Reconsideration." Studies in Canadian Literature 15(2):136–59.

- "George Johnson", Canadian Online Encyclopedia

- Fee, Margery and Dory Nason. Tekahionwake: E. Pauline Johnson's Writings on Native North America, Broadview Editions. Broadview Press.

- Gray, Charlotte. 2002. Flint & Feather: The Life and Times of E. Pauline Johnson, Tekahionwake (1st ed.). Toronto: HarperFlamingo Canada. ISBN 0-00-200065-2.

- Robinson, Amanda. "Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake)".

- Jackel, David. 1983. "Johnson, Pauline." In The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature, edited by W. Toye. Toronto: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-540283-9.

- Johnston, Sheila M.F. (1997). Buckskin & Broadclot: A Celebration of E. Pauline Johnson Tekahionwake, 1861–1913. Toronto: Natural Heritage, Natural History. ISBN 1-896219-20-9.

- Strong-Boag, Veronica, and Carole Gerson. 2000. Paddling Her Own Canoe: The Times and Texts of E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-4162-0.

- Adams, John Coldwell (2007). Pauline Johnson. Confederation Voices: Seven Canadian Poets. Canadian Poetry Press. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- Gerson, Carole (1998). "The Most Canadian of all Canadian Poets': Pauline Johnson and the Construction of a National Literature". Canadian Literature. 158: 90–107.

- Michelle A. Hamilton, Collections and Objections: Aboriginal Material Culture in Southern Ontario. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2010

- "Pauline Johnson Biography," Famous Biographies, QuotesQuotations.com, Web, 30 April 2011.

- Monture, Rick (2002). "Beneath the British Flag: Iroquois and Canadian Nationalism in the Work of Pauline Johnson and Duncan Campbell Scott". Essays on Canadian Writing. limited access. 75: 118–141

- Johnson, E. Pauline. Legends of Vancouver. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- Van Steen, Marcus (1965). Pauline Johnson: Her Life and Work. Toronto: Hodder & Stoughton.

- Keith, W. J. 2002. "2040." Canadian Book Review Annual. Toronto: Peter Martin Associates

- Atwood, Margaret. 1991. "A Double-Bladed Knife: Subversive Laughter in Two Stories by Thomas King." In Native Writers and Canadian Writing (special issue; reprinted ed.), edited by W. H. New. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 243. ISBN 0-7748-0371-1.

- Cruickshank, Ainslie (7 December 2017). "Toronto music teacher sues after principal, VP call folk song racist". Toronto Star.

- Gray, Charlotte. "The true story of Pauline Johnson: poet, provocateur and champion of Indigenous rights". Canadian Geographic.

- Monture, Rick.

75 (2002): 118–41. Print.'Beneath the British Flag'

: Iroquois and Canadian Nationalism in the Work of Pauline Johnson and Duncan Campbell Scott. - "E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake)".

- Johnson, E. Pauline National Historic Person. Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Parks Canada.

- "Home — Chiefs Wood". chiefswood.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2007.

- "Ontario Plaque". ontarioplaques.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011.

- Video for At Sunset performed by Canadian Chamber Choir on YouTube

- In Good Company, Canadian Chamber Choir CD including "At Sunset"

- "Margaret Atwood's opera debut 'Pauline' opens in Vancouver". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 23 May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- "Final 5 candidates for next Canadian woman on banknote revealed by Bank of Canada". cbc.ca.

Further reading

| Library resources about E. Pauline Johnson |

| By E. Pauline Johnson |

|---|

- Crate, Joan. Pale as Real Ladies: Poems for Pauline Johnson, London, ON: Brick Books, 1991. ISBN 0-919626-43-2

- Johnson (Tekahionwake), E. Pauline. E. Pauline Johnson Tekahionwake: Collected Poems and Selected Prose. Ed. Carole Gerson and Veronica Strong-Boag. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8020-3670-8

- Keller, Betty. Pauline: A Biography of Pauline Johnson. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1981. ISBN 0-88894-322-9.

- Mackay, Isabel E. Pauline Johnson : a reminiscence . 1913.

- McRaye, Walter. Pauline Johnson and Her Friends. Toronto: Ryerson, 1947.

- Shrive, Norman (1962). "What Happened to Pauline?". Canadian Literature. 13: 25–38.

- Poet, Princess, Possession: Remembering Pauline Johnson, 1913, in Seeing Red: A History of Natives in Canadian Newspapers, by Mark Cronlund Anderson and Carmen L. Robertson (University of Manitoba Press, 2011

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: E. Pauline Johnson |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Pauline Johnson |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pauline Johnson. |

- Biography of Emily Pauline Johnston at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- "E. Pauline Johnson fonds". McMaster University Library. The William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- Chiefswood National Historic Site

- "Pauline." Opera by Atwood and Stokes. 2014

- "McMaster Celebrates Canada 150 - from the Archives — E. Pauline Johnson". The William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

Works

- Works by E. Pauline Johnson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Emily Pauline Johnson at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about E. Pauline Johnson at Internet Archive

- Works by E. Pauline Johnson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Selected Poetry of E. Pauline Johnson - Biography and 5 poems (Brier: Good Friday, Flint and Feather, The Pilot of the Plains, Shadow River: Muskoka, The Song my Paddle Sings)

- 1895. The White Wampum. London: John Lane.

- Poems by E. Pauline Johnson