Edward Despard

Edward Marcus Despard (1751 – 21 February 1803), an Irish officer in the service of the British Crown, gained notoriety as a colonial administrator for refusing to recognise racial distinctions in law and, following his recall to London, as a republican conspirator. Despard's associations with the London Corresponding Society, the United Irishmen and United Britons led to his trial and execution in 1803 as the alleged ringleader of a plot to assassinate the King.

Edward Marcus Despard | |

|---|---|

Attributed to George Romney | |

| Born | 1751 Coolrain, Camross, Queens County, Kingdom of Ireland |

| Died | 21 February 1803 |

| Cause of death | Executed for High Treason |

| Nationality | |

| Occupation | Soldier, Colonial Administrator, Revolutionary |

| Employer | |

| Movement | |

Military service in the Caribbean

Edward Despard was born in 1751 in Coolrain, Camross, Queens County,[1] in the Kingdom of Ireland to a Protestant Anglo-Irish family of Huguenot descent. He was one of five brothers all of whom, save the eldest who inherited the family estate, served in the British military.[2] An elder brother, John Despard (1745–1829), rose to the rank of full General.

Despard “acquired the character, the manner, and the habits of a gentleman, and a soldier” as a page, from age eight, in the household of the Lord Hertford (Ambassador to France, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland).[3] In 1766, age fifteen, Despard entered the British Army as an Ensign in the 50th Foot.[4]

Posted with his regiment to Jamaica, Despard served as a defence-works engineer and in 1772 was promoted to Lieutenant.[5] His work required him to lead "motley crews", including free blacks, Miskitos and others of mixed-ancestry. In "forming and coordinating the gangs of workers whose labor was his triumph", it has been suggested that Despard was "creolized” in his sympathies".[6]

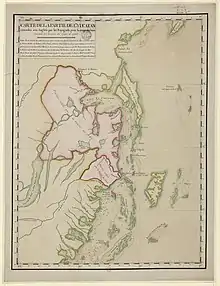

During the American War of Independence Despard served with distinction in sea-borne descents upon the Spanish Kingdom of Guatemala. He fought alongside Horatio Nelson (and attained the rank of captain) in the San Juan expedition of 1780. Two years later he commanded the British force that in the Battle of the Black River recovered British settlements on the Miskito Coast after having the driven the Spanish from the area, for which he received a royal commendation and the rank of colonel.[7] While leading reconnoitring missions, Despard again worked intimately with the African-Indian Miskitos[8] Olaudah Equiano, a former slave who had lived among them in the 1770s, recorded that "These Indians live under an almost perfect equality, and there are no rich or poor among them. They do not strive to accumulate, and the great unwearied exertion, found among our civilised societies, is unknown among them".[9]

Enforcing "English law" in the Bay of Honduras

After the Peace of Paris which concluded the war in 1783 Despard was made Superintendent of the British logwood concessions in the Bay of Honduras (present-day Belize). As directed from London. Despard sought to accommodate British subjects, the "Shoremen", displaced in the evacuation agreed with the Spanish (Convention of London 1786) of the Miskito Coast. To the dismay of the established "Baymen" (slave-holding loggers), Despard did so without "any distinction of age, sex, character, respectability, property or colour".[10] He distributed land by lottery in which, the Baymen noted in their petition to London, "the meanest mulatto or free negro has an equal chance".[11][12]

To the suggestion from the Home Secretary, Lord Sydney, that it was impolitic to put "affluent settlers and persons of a different description, particularly people of colour" on an "equal footing", Despard replied "the laws of England ... know no such distinction". (He had, on the same principle, overruled a local law excluding Jewish merchants from the Bay). Moved by the Baymen's entreaty that under "Despard's constitution" the "negroes in servitude, observing the now exalted status of their brethren of yesterday [the free, and now propertied, blacks among the Shoremen] would be induced to revolt, and the settlement must be ruined ", in 1790 Sydney's successor, Lord Grenville, recalled Despard to London.[13][14]

Catherine Despard, "mixed" marriage

Before leaving the Bay, in 1790 Despard had married Catherine, a black woman, by some accounts the daughter of a Jamaican preacher, by others an educated Spanish creole. He arrived in London together with her and their young son, James, as his acknowledged family. There was scarcely precedent in England for what was considered a "mixed-race" marriage. Yet in what may be "a marker of the more fluid and tolerant character of racial attitudes in the Age of Reform", their marriage does not appear to have been publicly challenged.[15]

When following Despard's arrest in 1798, the government sought to discredit Catherine's articulate intercessions on her husband's behalf, they thought it sufficient to observe that she was of the "fair sex". On the floor of the Commons John Courtenay MP (an Irishman), read a letter from Catherine in which she described her husband as being held "in a dark cell, not seven feet square, without fire, or candle, chair, table, knife, fork, a glazed window, or even a book". In reply, the attorney general Sir John Scott suggested that Catherine was being used as a mouthpiece by political subversives: "it was a well-written letter, and the fair sex would pardon him, if he said it was a little beyond their style in general".[16]

At the time of the Despards’ arrival in London, the virtue of openly mixed race marriages was being championed by Olaudah Equiano. Equiano, touring with his autobiography and abolitionist polemic The Interesting Narrative of the Life of ... The African and himself married to an English woman, asked: "Why not establish intermarriage at home, and in our colonies, and encourage open, free and generous love, upon Nature’s own wide and extensive plan, subservient only to moral rectitude, without distinction of the colour of a skin?"[17]

The next generation of Despards denied Edward and Catherine's marriage. Family memoirs referred to Catherine as his "black housekeeper", and "the poor woman who called herself his wife". James was ascribed to a previous lover, both of whom were written out of the family tree.[12]

Irish radical in London

Pitt's "Reign of Terror"

Without a further commission and having been pursued by his enemies in the Bay with lawsuits, in London Despard found himself confined for two years in a debtors' prison. There he read Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man. A response to Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France, it was a vindication of the “wild and Levelling principle of Universal Equality” he been accused of administering in the Bay.[18]

By the time Despard was released from the King's Bench Prison in 1794, Paine had been forced to take refuge in the new French Republic, with which the British Crown was now at war, and in both Britain and Ireland some of his more ardent admirers were beginning to consider universal franchise and annual parliaments a cause for physical force.

In October 1793, a British Convention in Edinburgh, with delegates from English corresponding societies attending, was broken up by the authorities on charges of sedition. Joseph Gerrald and Maurice Margarot of the London Corresponding Society and their host Thomas Muir of the Society of the Friends of the People were sentenced to fourteen years transportation. When in May 1794 an attempt to indict the radical English MP John Horne Tooke for treason misfired with a jury, the ministry of William Pitt renewed what was to have been an eight-month suspension of Habeas Corpus.

In summer of 1795 crowds shouting "No war, no Pitt, cheap bread" attacked the prime minister's residence in Downing Street and surrounded the King in procession to Parliament. There was also a riot at Charing Cross at the scene of which Despard was detained and questioned, something which a magistrate suggested Despard might have avoided had he not, in giving his name, used the "improper title" of "citizen".[19] In October, the government introduced the "Gagging Acts" (Seditious Meetings Act and the Treason Act), which outlawed "seditious" gatherings and rendered even the "contemplation" of force a treasonable offense.[20][21]

United Britons

Despard joined the London Corresponding Society (LCS), and was quickly taken on to its central committee. He also took the United Irish pledge (or "test") "to obtain an equal, full and adequate representation of all the people of Ireland" in a sovereign parliament in Dublin. At a time when the Irish movement was turning increasingly towards the prospects for a French-assisted insurrection, Despard would have found it represented in LCS and other radical circles in London, by the brothers Arthur and Roger O'Connor, and by Jane Greg.[22][23]

In the summer of 1797 James Coigly, a Catholic priest who had risen to prominence among the United Irishmen during the Armagh Disturbances,[24] arrived from Manchester where he had been administering as a test for "United Englishmen" an oath to "Remove the diadem and take off the crown... [to] exalt him that is low and abuse him that is high".[25] In London, convening what were variously called "True" or "United Britons", Coigly met with the leading Irish member of the LCS: in addition to Despard, Society President Alexander Galloway, and the brothers Benjamin and John Binns. Meetings were held at Furnival’s Inn, Holborn, where delegates from London, Scotland and the regions committed themselves "to overthrow the present Government, and to join the French as soon as they made a landing in England"[24] (in December 1796 only weather had prevented a major French landing in Ireland).

In December 1797 Coigly returned from France with news of French plans for an invasion, but in March 1798 when seeking again to cross the Channel in a party of five he and Arthur O'Connor were arrested. O'Connor, able to call Charles James Fox, Richard Sheridan and Henry Grattan in his defence, was acquitted. Coigly had been caught with a letter to the French Directory from the United Britons was convicted of treason and hanged in June. While its suggestion of a mass movement primed for insurrection had been scarcely credible, it was sufficient proof of the intent was to invite and encourage a French descent.[24]

Detention

The government swooped on the London Corresponding Society. Despard was detained at lodgings in Soho, where the Times reported he had been found in bed with "a black woman" (his wife, Catherine). Along with around thirty others, he was detained without charge in Coldbath Fields, a recently rebuilt high security prison in Clerkenwell.[12] Edward Despard, despite Catherine's lobbying efforts, was held for three years.

During this time the authorities were more than ready to see the hand not only of English radicals but also, with a large Irish contingent among the sailors, of United Irishmen in the Spithead and Nore mutinies of April and May 1797. The seized upon the leading role of Valentine Joyce at Spithead, described by Edmund Burke as "seditious Belfast clubist”.[26] Further repressive measures followed. The Corresponding Societies were comprehensively suppressed and the Combination Laws of 1799 and 1800 rendered union activity among workers criminal.

With hostilities with France suspended by the Treaty of Amiens, Despard, who had not been charged, was released in May 1802. Between then and February 1802 he may have visited a still disordered Ireland. In his home county of Queens government informers were reporting that while the Rebellion that had flared in 1798 had been "put down" it was "by no means suppressed. The blaze is only smothered".[27]

Treason trial

In London, Despard was arrested 16 November 1802 while attending a meeting of 40 working men at the Oakley Arms public house in Lambeth. Taken in chains to be interrogated by the Privy Council the next day, he was charged with High Treason. Government informers named him as the ringleader in a leader of a United Britons conspiracy to assassinate King George III and seize the Tower of London and Bank of England. Despard was prosecuted by Attorney General Spencer Perceval, before Lord Ellenborough, the Lord Chief Justice in a Special Commission on Monday, 7 February 1803.

Perceval had evidence that others in the club room of the Oakley Arms had discussed an insurrectionary plot with connections (he did not see fit to detail in court) to a northern underground: United Britons committed to rise on news of a coup in London. To implicate Despard, he relied heavily on the many mentions of his name in United Irish correspondence. But at "several stages removed from the colonel's actions" these were often from persons Despard had never met.[28]

Lord Nelson, then famous for the Battle of the Nile, made a dramatic appearance as a character witness in Despard's defence: "We went on the Spanish Main together; we slept many nights together in our clothes upon the ground; we have measured the height of the enemies wall together. In all that period of time no man could have shewn more zealous attachment to his Sovereign and his Country". But Nelson had to admit to having "lost sight of Despard for the last twenty years."[29][30] The same was conceded by General Sir Alured Clarke and Sir Evan Nepean who similarly testified to Despard's military service.[31]

In the end the jury was satisfied with a prosecution case that connected Despard to only one overt act: the administration of illegal oaths. But perhaps moved by the Vice-Admiral's testimony, they recommended clemency. In denying their motion, Ellenborough emphasised the revolutionary nature of Despard's purpose: not only to rend the new union between Great Britain and Ireland, but to affect "the forcible reduction to one common level of all the advantages of property, of all civil and political rights whatsoever".[32] Together with John Wood, 36, John Francis, 23, both privates in the army, Thomas Broughton, 26, a carpenter, James Sedgwick Wratton, 35, a shoemaker, Arthur Graham, 53, a slater, and John Macnamara, a labourer, Despard was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered.[7]

Catherine Despard persisted with her campaign on her husband's behalf. With Nelson's assistance she interceded with the Prime Minister and the King, but secured only a waiving of the already archaic rites of disembowelment and dismemberment.[33]

Execution

Edward Despard was hanged and decapitated on the roof of the gatehouse at Horsemonger Lane Gaol on 21 February 1803. The authorities had feared a public demonstration. Constables were ordered to watch “all the public houses and other places of resort for the disaffected,” and the jail keeper was issued a rocket to launch as a signal to the military in the event of trouble.[34]

Despard had declined to take divine service. He offered that while "outward forms of worship were useful for political purposes", he thought "the opinions of Churchmen, Dissenters, Quakers, Methodists, Catholics, Savages, or even Atheists, were equally indifferent". He was permitted a final meeting with his wife during which, according to reports, "the Colonel betrayed nothing like an unbecoming weakness".[35]

With the hangman’s noose loosely around his neck, Despard stepped to the edge of the platform, and addressed a crowd, estimated at twenty thousand (until the funeral of Lord Nelson following the Battle of Trafalgar the largest gathering London had witnessed), with words Catherine may have helped him prepare:[36]

Fellow Citizens, I come here, as you see, after having served my Country faithfully, honourably and usefully, for thirty years and upwards, to suffer death upon a scaffold for a crime which I protest I am not guilty. I solemnly declare that I am no more guilty of it than any of you who may be now hearing me. But though His Majesty’s Ministers know as well as I do that I am not guilty, yet they avail themselves of a legal pretext to destroy a man, because he has been a friend to truth, to liberty, and to justice

[a considerable huzzah from the crowd]

because he has been a friend to the poor and to the oppressed. But, Citizens, I hope and trust, notwithstanding my fate, and the fate of those who no doubt will soon follow me, that the principles of freedom, of humanity, and of justice, will finally triumph over falsehood, tyranny and delusion, and every principle inimical to the interests of the human race.

[a warning from the Sheriff ]

I have little more to add, except to wish you all health, happiness and freedom, which I have endeavoured, as far as was in my power, to procure for you, and for mankind in general.

Epilogue

Catherine Despard's final service to her husband was to insist on his hereditary right to be buried in St Faith's in the City of London, an old graveyard that had been subsumed within the walls of St Paul's Cathedral, a campaign she won despite protests to the government from the Lord Mayor of London. On the day of the funeral (held Match 1st to allow their son James serving in the French army to return from Paris), lined the street from their last residence in Lambeth, across Blackfriars Bridge, towards St Paul's, at which point they dispersed in silence.[37]

After his death, there was a report of Catherine Despard being taken under the "protection" of Lady Nelson.[38] The MP Sir Francis Burdett, who with Horne Tooke had assisted in the defence, helped arrange a pension. She spent some time in Ireland, a guest of Valentine Lawless, 2nd Baron Cloncurry who had been detained with Despard in 1798. Catherine Despard died in Somers Town, London, in 1815.[39]

Their son James returned to Britain after the Napoleonic Wars. The final trace of him in the family records is an episode recounted by General John Despard, Edward's older brother, who was leaving a London theatre when he heard a carriage driver calling the family name. He made his way towards the carriage he assumed was his, "and there appeared a flashy Creole and a flashy young lady on his arm, and they both stepped into it."[40]

In popular culture

Edward Despard appears as a character in the fifth (2015) series of the popular British television drama Poldark, played by Vincent Regan .[41] The screenplay is based on the historical novels of Winston Graham.

References

- Dooley, Gerard (2015). Camross: Her People, Their Story. Roscrea. p. 50.

- Oman, Charles William Chadwick (1922), Unfortunate Colonel Despard and Other Studies. London, Burt Franklin. p.2

- Conner, Clifford (2000). Colonel Despard: The Life and Times of an Anglo-Irish Rebel. Cambridge MA: Da Capo Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1580970266.

- Oman p.2

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Despard, Edward Marcus". Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 101.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Despard, Edward Marcus". Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 101. - Linebaugh, Peter; Rediker, Marcus (2000). The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 258–261. ISBN 9780807050071.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Conner (2000), pp. 47-48

- Conzemius, Philip (1932). Ethnographical Survey of the Miskito and Sumu Indians of Honduras and Nicaragua. Washington DD: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 106. p. 48.

- Burns, Alan (1965). History of the British West Indies (Second ed.). New York: Allen & Unwin. p. 541. ISBN 9780849019890.

- Campbell, Mavis (2003). ""St George's Cay: Genesis of the British Settlement of Belize – Anglo-Spanish Rivalry". The Journal of Caribbean History. 37 (2): 171–203.

- Jay, Mike (2004). The Unfortunate Colonel Despard. London: Bantam Press. p. 147. ISBN 0593051955.

- Linebaugh and Rediker (2000), p. 273

- Jay (2004) pp. 145-147, 158-159

- Gillis, Bernadette (August 2014). A Caribbean Coupling Beyond Black and White: The Interracial Marriage of Catherine and Edward Marcus Despard and its Implications for British Views on Race, Class, and Gender during the Age of Reform (PDF). Durham, North Carolina: Graduate School of Duke University. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Linebaugh, Peter (2019). Red Round Globe Hot Burning. Oakland CA: University of California Press. pp. 365–367. ISBN 9780520299467.

- Blackburn, Robin (21 November 2005). "The True Story of Equiano". The Nation. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- "Petition by Settlers against Despard's Constitution" (1788) cited in Jay (2004), p. 153

- Gillis, Bernadette (August 2014). A Caribbean Coupling Beyond Black and White: The Interracial Marriage of Catherine and Edward Marcus Despard and its Implications for British Views on Race, Class, and Gender during the Age of Reform (PDF). Durham, North Carolina: Graduate School of Duke University. pp. 37–38. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Emsley, Clive (1985). "Repression, 'terror', and the rule of law in England during the decade of the French Revolution". English Historical Review. 100 (31): 801–825. doi:10.1093/ehr/C.CCCXCVII.801.

- Jay (2004) pp. 231-232

- Smith, A.W (1995). "Irish Rebels and English Radicals 1798-1820. Past & Present". JSTOR 650175. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kennedy, Catriona (2004). "'Womanish Epistles?' Martha McTier, Female Epistolarity and Late Eighteenth-Century Irish Radicalism". Women's History Review. 13 (1): 660. doi:10.1080/09612020400200404. S2CID 144607838. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Keogh, Dáire (1998). "An Unfortunate Man". 18th–19th - Century History. 6 (2). Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Davis, Michael. "United Englishmen". OxfordDNB. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Manwaring, George; Dobree, Bonamy (1935). The Floating Republic: An Account of the Mutinies at Spithead and the Nore in 1797. London: Geoffrey Bles. p. 101.

- Linebaugh (2019), p.317

- Jay 2004), pp. 276, 288

- Gurney, William Brodie; Gurney, Joseph (1803). The Trial of Edward Marcus Despard, Esquire: For High Treason, at the Session House, Newington, Surrey, On Monday the Seventh of February, 1803. London: M Gurney. p. 176.

- Agnew, David (1886). Protestant exiles from France, chiefly in the reign of Louis XIV; or, The Huguenot refugees and their descendants in Great Britain and Ireland. Volume 1 (Third ed.). For Private Circulation. p. 204. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- Jay (2008), p. 297

- quoted Linebaugh (2019) p. 39

- Jay (2008), p.301

- Jay (2008> pp. 2-3

- Jay (2008), pp. 300-304

- Linebaugh, Peter (2019). Freedom, Humanity, and Justice: A Tale at the Crossroads of Commons and Closure, of Love and Terror, of Race and Class, and of Kate and Ned Despard. Oakland CA: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520299467. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- Jay (2008), pp. 307-308

- Gillis, Bernadette (August 2014). A Caribbean Coupling Beyond Black and White: The Interracial Marriage of Catherine and Edward Marcus Despard and its Implications for British Views on Race, Class, and Gender during the Age of Reform (PDF). Durham, North Carolina: Graduate School of Duke University. pp. 51–52. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Linbaugh (2019), pp. 21-23

- Jay (2008) p. 310

- Fearn, Rebecca (21 July 2019). "Was Colonel Ned Despard A Real Person? 'Poldark's New Character Has An Interesting Story". Bustle. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

Bibliography

- Conner, Clifford D., Colonel Despard: The Life and Times of an Anglo-Irish Rebel. Combined Publishing, 2000. ISBN 978-1580970266.

- Jay, Mike, The Unfortunate Colonel Despard. Bantam Press, 2004. ISBN 9781472144065.

- Linebaugh, Peter. Red Round Globe Hot Burning. University of California Press, 2019. ISBN 9780520299467.

- Oman, Charles William Chadwick. Unfortunate Colonel Despard and Other Studies. Burt Franklin, 1922.

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by James Lawrie |

Superintendent of British Honduras 1787–1790 |

Succeeded by Peter Hunter |