Society of United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen, also simply known as the United Irishmen, were a sworn society in the Kingdom of Ireland formed in the wake of the French Revolution to secure "an equal representation of all the people" in a "national government." Despairing of constitutional reform, in 1798 the Society instigated a republican insurrection in defiance of British Crown forces and of Irish sectarian division. Their suppression was a prelude to the abolition of the Protestant Ascendancy Parliament in Dublin and to Ireland's incorporation in a United Kingdom with Great Britain.

| |

| Leaders | James Coigly, William Drennan, Michael Dwyer, Thomas Addis Emmet, Lord Edward FitzGerald, James Hope, Henry Joy McCracken, Samuel Neilson, Thomas Russell, William Tennant, Theobald Wolfe Tone |

| Founded | 1791 Belfast |

| Dissolved | 1804 |

| Headquarters | Dublin |

| Newspaper | Northern Star (Belfast), The Press (Dublin). |

| Ideology | Liberalism Nationalism Republicanism |

| Political position | Centre-left |

| International affiliation | Allied to the French First Republic, United Scotsmen, United Englishmen/United Britons. |

| Colors | Green |

| Party flag | |

| |

Background

Dissenters: "Americans in their hearts"

The men who, in October 1791, gathered in a Belfast tavern to propose a reform of the Irish Parliament on "principles of civil, political and religious liberty"[2] were Protestants in what was then a largely Protestant town. With the exception of Thomas Russell, a former India-service army-officer from Cork, and Theobald Wolfe Tone, a Dublin barrister, they were Presbyterians. As Dissenters from the established Anglican (Church of Ireland) communion they were conscious of having shared, in part, the civil and political disabilities of the Kingdom's dispossessed Roman Catholic majority.

The Parliament in Dublin did not exclude Presbyterians. In 1790 the son of an exceptionally wealthy Presbyterian family, Robert Stewart (Viscount Castlereagh), had won a county seat south of Belfast with the promise of reform. But with the seat's comparatively large number of freehold voters, his election represented a rare contest. Two-thirds of the Irish House of Commons represented boroughs in the pockets of the Kingdom's largest landowners. Belfast's two MPs were elected by the thirteen members of the corporation, all nominees of the Chichesters, Marquesses of Donegall. Faced with the tithes, rack rents and sacramental tests of this Ascendancy, and with English restrictions on Irish manufacture, Presbyterians had been voting by leaving Ireland in ever greater numbers. From 1710 to 1775 over 200,000 sailed for the North American colonies. When the American Revolutionary War commenced in 1775, there were few Presbyterian households that did not have relatives in America, many of whom would take up arms against the Crown.[3]

Most of the Society's founding members and leadership were members of Belfast's first three Presbyterian churches, all in Rosemary Street. Henry Joy McCracken, born into the town's leading fortunes in shipping and linen-manufacture, was a Third Church member; Samuel Neilson, owner of the largest woollen warehouse in Belfast, was in the Second Church; and the obstetrician William Drennan, who called the inaugural meeting, was the son of the minister of the First Church. Despite theological differences (the First and Second Churches did not subscribe to the Westminster Confession of Faith), the Rosemary Street churches were of a broadly "New Light" persuasion.[4] Educated at the University of Glasgow, their elected ministers inclined in their teaching toward conscience and "the light of nature" rather than doctrine.[5]

The University of Glasgow, which Drennan himself had attended from 1769 to 1772, had become the centre of the Scottish Enlightenment. In their defence of what Drennan called "the restless power of reason", a new generation of Scottish thinkers had drawn on the republican ethos of Presbyterian resistance to royal and episcopal imposition.[6] In the cases of David Hume (1711-1776), Adam Smith (1723-1790) and Adam Ferguson (1723-1816) they also drew directly upon the work of the Irish Presbyterian Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746). At Glasgow Hutcheson had held the Chair of Moral Philosophy and had led those in the Church of Scotland opposed to the Old Light Calvinist doctrines of a fallen humanity. But his influence would also reach Ireland via America. Hutcheson's early Inquiry into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue (1725), introducing his "perennial association of unalienable rights with the collective right to resist oppressive government", served at Harvard College as a textbook as early as the 1730s.[7] Thomas Jefferson's appeals to sentiment in the Declaration of Independence (broadcast in August 1776 by the Belfast News Letter) are thought to reflect Hutcheson's influence.[8]

Hutcheson's benevolent theory of morals supported concepts of Natural Law and of rights consistent with the case for limited and accountable government.[9] As proposed by John Locke (1632-1704, whose Treatises on Government Drennan cited as his "prime authority on politics"),[10] in England, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 was understood as an advance on broadly these principles.

In Ireland the outworkings of James the Second's deposition in 1688 differed from those in England. By further concentrating land in Anglican hands, the Williamite Settlement established the Dublin Parliament on a still narrower Ascendancy basis. It also confirmed the Kingdom's subordination to the Crown in England. The King's ministers in London held the Dublin Castle Executive to account through the office of the Lord Lieutenant; they approved and amended heads of Irish parliamentary bills; and could, through the parliament at Westminster, pass their own legislation for Ireland. As a result, the United Irishmen held, Ireland had "no national government". It was ruled, rather, "by Englishmen, and the servants of Englishmen."[11]

Aware of their growing political disaffection, the Lord Lieutenant, Lord Harcourt (in office 1772-1776), reported to Dublin Castle that the Presbyterians of Ulster were Americans "in their hearts".[12]

The Volunteers and Parliamentary Patriots

For the Belfast members of the Society, there was a further source of prior association, the Irish Volunteer companies formed during the American War. While in many areas the new militia were little more than local landlords and their retainers armed and drilled, in Dublin, in the larger towns and in Presbyterian Ulster where half of all Ireland's Volunteers were based, they mobilised a wider section of Protestant society.[14][15]

In April 1782, with Volunteer cavalry, infantry, and artillery posted on all approaches to the Parliament in Dublin, Henry Grattan, leader of the Patriot opposition, had a Declaration of Irish Rights carried by acclaim in the Commons. London conceded, surrendering its powers to legislate for Ireland. In 1783 Volunteers converged again upon Dublin, this time to support a bill presented by Grattan's patriot rival, Henry Flood, to abolish the proprietary boroughs and to extend the vote to a broader class of Protestant property holders. But the Volunteer moment had passed. Having accepted defeat in America, Britain could again spare troops for Ireland, and the limits of the Ascendancy's patriotism had been reached. Parliament refused to be intimidated.[16]

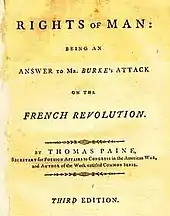

With the news in 1789 of revolutionary events in France enthusiasm for constitutional reform revived. In Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen France, the greatest of the Catholic powers, was seen to be undergoing its own Glorious Revolution. In his Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), Edmund Burke had sought to discredit any analogy with 1688. But on reaching the Belfast in October 1791, Tone found that Thomas Paine's response to Burke, the Rights of Man (which ran into several Irish editions), had won the argument.[17]

Three months before, on 14 July, the second anniversary of the Fall of the Bastille was celebrated with a triumphal procession through Belfast and a solemn Declaration to the Great and Gallant people of France: "As Irishmen, We too have a country, and we hold it very dear—so dear... that we wish all Civil and Religious Intolerance annihilated in this land."[18] Bastille Day the following year was greeted with similar scenes and an address to the French National Assembly hailing the soldiers of the new republic as "the advance guard of the world".[19]

Belfast debates

First resolutions

.jpg.webp)

It was in the midst of this enthusiasm for events in France[21] that William Drennan proposed to his friends "a benevolent conspiracy—a plot for the people", the "Rights of Man and [employing the phrase coined by Hutcheson] the Greatest Happiness of the Greater Number its end—its general end Real Independence to Ireland, and Republicanism its particular purpose."[22] When Drennan's friends gathered, they resolved:

--that the weight of English influence in the government of this country is so great as to require a cordial union among all the people of Ireland; [and] --that the sole constitutional mode by which this influence can be opposed, is by complete and radical reform of the representation of the people in parliament.[23]

The "conspiracy", which at Tone's suggestion called itself the Society of the United Irishmen, had moved beyond Flood's Protestant patriotism. English influence, exercised through the Dublin Castle Executive, would be checked constitutionally by a parliament in which "all the people" would have "an equal representation." Unclear, however, was whether the emancipation of Catholics was to be unqualified and immediate. The previous evening, witnessing a debate over the Catholic Question between the town's leading reformers (members of the Northern Whig Club) Tone had found himself "teased" by people agreeing in principle to Catholic emancipation, but then proposing that it be delayed or granted only in stages.[24]

The Catholic Question

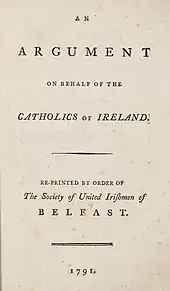

Thomas Russell had invited Tone to the Belfast gathering in October 1791 as the author of An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland.[25] In honour of the reformers in Belfast, who arranged for the publication of 10,000 copies, this had been signed A Northern Whig. Being of French Huguenot descent, Tone may have had an instinctive empathy for the religiously persecuted, but he was "suspicious of the Catholics priests" and hostile to what he saw as "Papal tyranny".[26] (In 1798 Tone applauded Napoleon's deposition and imprisonment of Pope Pius VI).[27]

For Tone the argument on behalf of the Catholics was political. The "imaginary Revolution of 1782" had failed to secure a representative and national government for Ireland because Protestants had refused to make common cause with Catholics. In Belfast the objections to doing so were rehearsed for him again by the Reverend William Bruce. Bruce spoke of the danger of "throwing power into hands" of Catholics who were "incapable of enjoying and extending liberty," and whose first interest would be to reclaim their forfeited lands.[28]

In his Argument Tone insisted that, as a matter of justice, men cannot be denied rights because an incapacity, whether ignorance or intemperance, for which the laws under which they are made to live are themselves responsible. He also appealed to historical experience. When they had the opportunity in the Parliament summoned by James II in 1689, and clearer title to what had been forfeit not ninety but forty years before (in the Cromwellian Settlement), Catholics did not insist upon a wholesale return of their lost estates. As to the existing Irish Parliament "where no Catholic can by law appear", it was the clearest proof that "Protestantism is no guard against corruption".

Tone cited the examples of the American Congress and French National Assembly where "Catholic and Protestant sit equally" and of the Polish Constitution of May 1791 (also celebrated in Belfast)[29] with its promise of amity between Catholic, Protestant and Jew. If Irish Protestants remained "illiberal" and "blind" to these precedents, Ireland would continue to be governed in the exclusive interests of England and of the landed Ascendancy.[30]

On Bastille Day 1792 in Belfast, the United Irishmen had occasion to make their position clear. In a public debate on An Address to the People of Ireland, William Bruce and others proposed hedging the commitment to an equality of "all sects and denominations of Irishmen". They had rather anticipate "the gradual emancipation of our Roman Catholic brethren" staggered in line with Protestant concerns for security and with improving Catholic education. Samuel Neilson "expressed his astonishment at hearing... any part of the address called a Catholic question." The only question was "whether Irishmen should be free." William Steel Dickson, with "keen irony", wondered whether Catholics were to ascend the "ladder" to liberty "by intermarrying with the wise and capable Protestants, and particularly with us Presbyterians, [so that] they may amend the breed, and produce a race of beings who will inherit the capacity from us?"[31]

The amendment was defeated, but the debate reflected a growing division. The call for Catholic emancipation might find support in Belfast and surrounding Protestant-majority districts. West of the River Bann, and across the south and west of Ireland where Protestants were a distinct minority, veterans of the Volunteer movement were not persuaded. The Armagh Volunteers, who had called a Volunteer Convention in 1779, boycotted a third in 1793.[32] Under Ascendancy patronage they were already moving along with the Peep o' Day Boys, battling Catholic Defenders in rural districts for tenancies and employment, toward the formation in 1795 of the loyalist Orange Order.

Equal representation

In 1793 the Government itself breached the principle of an exclusively Protestant Constitution. Dublin Castle put its weight behind Grattan in the passage of a Catholic Relief Act. Catholics were admitted to the franchise (but not yet to Parliament itself) on the same terms as Protestants. This courted Catholic opinion, but it also put Protestant reformers on notice. Any further liberalising of the franchise, whether by expunging the pocket boroughs or by lowering of the property threshold, would advance the prospect of a Catholic majority.

Beyond the inclusion of Catholics and a re-distribution of seats it had not been clear what the United Irishmen intended by "an equal representation of all the people". While insisting that his "sentiments are not less liberal" than their own, in his News Letter Henry Joy warned the United Irishmen that entrusting liberty to a potentially, "ignorant, licentious, idle and profligate populace" was likely, as in ancient Rome, to "terminate in a dictatorship or empire."[33] Beginning with news of the September Massacres, many of his readers were to see in France the vindication of such caution. Yet, as they Society grew and replicated across the country it remained open to men of every station, those of humbler means being actively courted.

In 1793 Thomas Addis Emmet reported an influx of "mechanics [artisans, journeymen and their apprentices], petty shopkeepers and farmers".[34][35] Some of these were maintaining in Belfast, Derry, other towns in the North, and in Dublin, their own Jacobin Clubs. Writing to her brother, William Drennan, in 1795 Martha McTier describes the Jacobins as an established democratic party in Belfast, composed of "persons and rank long kept down" and chaired by a "radical mechanick" (sic).[36] Yet the Club counted among its members the banker William Tennant, minister of Rosemary Street Third Presbyterian Sinclair Kelburn (much admired by Tone as a fervent democrat)[37] and other well-to-do United Irishmen.[38]

The overlap between the Clubs and the Society might suggest that the Jacobins "were an auxiliary group, perhaps encouraged to take a more radical stand" while the United Irishmen "awaited the outcome of the Catholic campaign for final repeal of the penal laws".[39] When April 1795 Earl Fitzwilliam, Lord Lieutenant for just fifty days, was recalled to London for publicly urging support for Emancipation, and the general prospects for reform appeared buried, the Jacobins with their radical ideas flooded United Irish societies. Unabashed republicans, with Kelburn they doubted that there "was any such thing" as Ireland's "much boasted constitution."[40] In correspondence with clubs in England and Scotland, some proposed that delegates from all three kingdoms convene to draft a "true constitution".[41]

This Painite radicalism had been preceded by an upsurge in trades union activity. In 1792 the Northern Star reported a "bold and daring spirit of combination" (long in evidence in Dublin) appearing in Belfast and surrounding districts. Breaking out first among cotton weavers, it then "communicated to the bricklayers, carpenters, etc." In the face of "demands made in a tumultuous and illegal manner", in the Northern Star, the movement paper to which he pledged his woollen business, Samuel Neilson came down upon the side of the authorities. Neilson did not doubt that the town's Sovereign (Lord Donegall's appointee) should have the support of the Volunteers in enforcing the laws against combination.[42][43] James (Jemmy) Hope, a self educated weaver, who joined the Society in 1796, nonetheless was to account Neilson, along with Russell (who in the Star positively urged unions for labourers and cottiers),[44] McCracken, and Emmet, the only United Irish leaders "perfectly" understood the real causes of social disorder and conflict: "the conditions of the labouring class".[45]

In November 1793 the leadership did commit to radical parliamentary reform. They called for equal electoral districts, annual parliaments, paid representatives and universal manhood suffrage.[46] This went beyond the dispensation the Belfast's reformers had celebrated in the French Constitution of 1791. Yet despite their broadening democratic base, the United Irishmen, as a body, do not appear to have considered the broader implications of a universal suffrage.[47]

The Dublin Society, formed within a month of Belfast, declared that it was to be a "principal rule of conduct... to attend those things in which we all agree, [and] to exclude those in which we differ". This did not imply an indifference to the issues. But the result was that as a movement, the United Irishmen were not associated with what could later be recognised as an economic or social programme.[48] Given the central role it was to play in the eventual development of Irish democracy, the most startling omission was the absence, beyond the disclaimer of wholesale Catholic restitution, of any scheme or principle land reform. Jemmy Hope might be clear that this should not be "a delusive fixity of tenure [that allows] the landlord to continue to draw the last potato out of the warm ashes of the poor man's fire".[49] But for the great rural mass of the Irish people this was an existential question upon which neither he nor any central resolution spoke for the Society.[47]

Women

As were Presbyteries, Volunteer companies and Masonic lodges through which they recruited, the United Irishmen were a male fraternity. In serialising William Godwin's Enquiry Concerning political Justice (1793), the Northern Star[51] had advised them of the moral and intellectual enlightenment found in an "equal and liberal intercourse" between men and women.[52] The paper had also reviewed and commended Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). But the call was not made for women's civic and political emancipation. In publishing excerpts from Wollstonecraft's work, the Star focussed entirely upon issues of female education.[53]

In the rival News Letter, William Bruce suggested that this was disingenuous: the "impartial representation of the Irish nation" the United Irishmen embraced in their test or oath implied, he argued, not only equality for Catholics but also that "every woman [emphasis added], in short every rational being shall have equal weight in electing representatives".[54][55] Drennan did not seek to disabuse Bruce as to "the principle"—he had never seen "a good argument against the right of women to vote"—but in a plea that recalled objections to immediate Catholic emancipation he argued for a "common sense" reading of the test of which he was the author. It might be some generations, he proposed, before "habits of thought, and the artificial ideas of education" are so "worn out" that it would appear "natural" that women should exercise the same rights as men, and thus attain their "full and proper influence in the world".[56]

In Belfast Drennan's sister Martha McTier and McCracken's sister Mary-Ann, and in Dublin Emmett's sister Mary Anne Holmes and Margaret King, shared in the reading of Wollstonecraft (and of other progressive women writers). As had Tone on behalf of Catholics, Wollstonecraft argued that the incapacities alleged to deny women equality were those that law and usage themselves impose. Mary Ann McCracken, in particular, was articulate in taking to heart the conclusion that women had to reject "their present abject and dependent situation" and secure the liberty without which they could "neither possess virtue or happiness".[57]

There is a suggestion that such women may have formed their own United Irish union. In October 1796 the Northern Star published a letter from the secretary of the Society of United Irishwomen. This blamed the English, who made war on the new republics, for the violence of the American and French Revolutions.[58] Denounced as a "violent republican", Martha McTier was the immediate suspect, but denied any knowledge of the society.[59] The true author may have been her friend Jane Greg, described by informants as "very active" in Belfast "at the head of the Female Societies",[60] (and by General Lake as being "the most violent creature possible").[61]

Mary Ann McCracken does make reference to "some female societies" in the town, but is clear that no women with "rational ideas of liberty and equality for themselves" would consent to a separate organisation. There could be "no other reason having them separate, but keeping the women in the dark" and making "tools of them".[62]

In final months before the rising, the paper of the Dublin society, The Press, published two direct addresses to Irish women, both of which "appealed to women as members of a critically-debating public":[63] the first (21 December 1797) signed "Philoguanikos" (probably the paper's founder, Arthur O'Connor), the second (1 February 1798) signed "Marcus" (Drennan). While both appealed to women to take sides, Philoguanikos was clear that women were being asked to act as political beings. He "scorns" those "brainless bedlams" who "scream in abhorrence of the idea of a female politician" and "the reasoning that says 'what has been, shall be'".

The letters of Martha McTier and Mary Ann McCracken testify to the role of women as confidantes, sources of advice and bearers of intelligence. R.R. Madden, one of the earliest historians of the United Irishmen, describes various of their activities in the person of an appropriately named Mrs. Risk.[64] By 1797 the Castle informer Francis Higgins was reporting that "women are equally sworn with men"[65] suggesting that some of the women assuming risks for the United Irish cause (possibly including McCracken)[66] were taking places beside men in an increasingly clandestine organisation. Middle-class women were reportedly active in the Dublin United Irishmen. William James MacNeven was sworn into the society by a woman.[67]

On the role in the movement of plebeian and peasant women there is a dearth of sources.[68] But in the 1798 uprising they came forward in many capacities, some, as celebrated in later ballads (Betsy Gray and Brave Mary Doyle, the Heroine of New Ross), as combatants.[69] Under the command of Henry Luttrell, Earl Carhampton (who, in a celebrated case in 1788, Archibald Hamilton Rowan had accused of child rape), troops treated women, young and old, with great brutality.[70]

Spread and radicalisation

Jacobins, Masons and Seceders

Jacques-Louis de Bougrenet de La Tocnaye, a French émigré who walked the length and breadth of Ireland in 1796–7, was appalled to encounter in a cabin upon the banks of the Upper Bann the same "nonsense on which the people of France fed themselves before the Revolution". A young labourer treated him to a disposition on "equality, fraternity, and oppression", "reform of Parliament", "abuses in elections", and "tolerance", and such "philosophical discourse" as he had heard from "foppish talkers" in Paris a decade before.[71] In 1793, a magistrate in that same area, near Coleraine, County Londonderry, had been complaining of "daily incursions of disaffected people... disseminating the most seditious principles".[72] Until his arrest in September 1796, Thomas Russell (later celebrated in a popular ballad as The man from God-knows-where) was one such outsider. Recruiting for the Society, he ranged from Belfast as far as Donegal and Sligo.

In calling town, parish and county meetings, and in seeking to form new local societies or chapters, agitators like Russell might look to enlist the support of Freemasons. Although it was the rule that "no politics must be brought within the doors of the Lodge", masons were involved in the Volunteer movement and their lodges remained "a battleground for political ideas".[73] Drennan, himself a mason, from the outset had anticipated that his "conspiracy" would have "much of the secrecy and somewhat of the ceremonial of Free-Masonry".[22]

As United Irishmen increasingly attracted the unwelcome attention of Dublin Castle and its network of informants, masonry did become both a host, a model and a cover.[74][75] The number of Masonic lodges themselves began to grow, although how far this might have been to accommodate the rival organising efforts of loyalists particularly on the sectarian frontiers of Armagh and Tyrone is unclear.[73]

From February 1793 the Crown was at war with the French Republic. This led immediately to heightened tensions in Belfast. On 9 March a body of dragoons rampaged through the town, purportedly provoked by taverns displaying the likenesses of Dumouriez, Mirabeau and Franklin.[76] They withdrew to barracks when, as related by Martha McTier, about 1,000 armed countrymen came into the town and mustered at McCracken's Third Presbyterian.[77] Further "military provocations" saw attacks on the homes of Neilson, Kelburn and other United Irishmen and on the offices of the Northern Star (wrecked for the final time, and closed, in May 1797). Legislation impressed from Westminster banned extra-parliamentary conventions and suppressed the Volunteers, by then largely a northern movement. They were replaced by a paid militia, its ranks partially filled with conscripted Catholics, and by Yeomanry, an auxiliary force led by local gentry.

While still free to associate, and in advance of their proscription in May 1794, the northern clubs had begun to take direction from a secret committee in Belfast. These included the first societies among the farmers and market-townsmen of north Down and Antrim, those among whom Jemmy Hope believed "the republican spirit, inherent in the principles of Presbyterian community, kept resistance to arbitrary power still alive."[78]

This spirit of resistance was not at odds with an older religious faith. It is estimated that about half the ministers of the Reformed Presbyteries in Ulster—those whose bible reading caused them to secede from the established Presbyterianism of Scotland—were implicated in the eventual rebellion.[79] Many were drawn to the United Irishmen by millenarian William Gibson who roamed County Antrim "to preach sedition and the word".[80]

In June 1795, members of the Northern Executive, including Russell, McCracken. Neilson and Robert Simms met with Tone who was en route to exile in the United States. At McArt's fort atop Cave Hill overlooking Belfast they swore the celebrated oath "never to desist in our efforts until we had subverted the authority of England over our country, and asserted our independence'".[81]

Alliance with the Catholic Defenders

_p111_PEEP-OF-DAY_BOYS.jpg.webp)

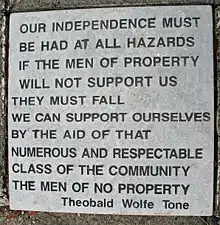

Drennan's original United Irish test, first taken in Dublin in December 1791, focused upon the "representation of the Irish nation in Parliament"[82] no longer spoke to the real object. With no further expectation of the Patriot gentry, but in hope of French assistance, this was to build a broad popular union to cut the tie to England, overturn the Ascendancy, and ensure a representation of the people that was "full and equal".[83] In March 1796 from Paris (to which he had travelled by way of Philadelphia) Tone recorded his understanding of the new resolve: "Our independence must be had at all hazards. If the men of property will not support us, they must fall; we can support ourselves by the aid of that numerous and respectable class of the community, the men of no property".[84]

The greatest body, existing, of men of no property, and with whom alliance was to be sought if there was to be a broad union of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter, were the Defenders.[85] A vigilante response to Peep O'Day raids upon Catholic homes in the mid 1780s, by the early 1790s the Defenders (drawing, like the United Irishmen, on the lodge structure of the Masons) were a secret oath-bound fraternity ranging across Ulster and the Irish midlands. Despite their professed loyalism (members had originally to swear allegiance to the King) Defenderism developed an increasingly a seditious character. Talk in the lodges was of a release from tithes, rents and taxes, and of a French invasion that might allow the repossession of Protestant estates.[86] Arms-buying delegations were sent to London.[87] The Government responded with increasing repression, seconded by the Peep O'Day Boys, local Volunteer companies and later by the Orange Order and the Yeomanry.

Defenders and United Irishmen began to seek one another out. Religion was not a bar to joining the Defenders. In Dublin, in particular, where the Defenderism appealed strongly to a significant body of radical artisans and petty shopkeepers, Protestants joined in the determination to make common cause. Oaths, catechisms and articles of association supplied to Dublin Castle nonetheless suggest the Defenders were developing a kind of Catholic "liberation theology"—their own version of Gibson's millenarianism. Apocalyptic biblical allusions and calls to "plant the true religion" sat uneasily with the rhetoric of inalienable rights and fealty to a "United States of France and Ireland".[88] Oblivious to the anti-clericalism of the French Republic, Defender rank-and-file tended to view the French through a Jacobite, not Jacobin, lens, as Catholics at war with Protestants.[89] Although Hope and McCracken did much to reach out to the Defenders, recognising the sectarian tensions (Simms reported to Tone that "it would take a great deal of exertion" to keep the Defenders from "producing feuds"), the Belfast Executive choose emissaries from its small number of Catholics.[90]

With their brother-in-law John Magennis, in 1795 the United Irish brothers, Bartholomew and Charles Teeling, sons of a wealthy Catholic linen manufacturer in Lisburn, appear to have had command over the Down, Antrim and Armagh Defenders.[91] United Irishmen were able to offer practical assistance: legal counsel, aid and refuge. Catholic victims of the Armagh disturbances and of the Battle of the Diamond (at which Charles Teeling had been present)[92] were sheltered on Presbyterian farms in Down and Antrim, and the goodwill earned used to open the Defenders to trusted republicans. Emmet records these as being able to convince Defenders of something they had only "vaguely" considered, namely the need to separate Ireland from England and to secure its "real as well as nominal independence".[93]

Dublin and the Catholic Committee

The Society Tone helped establish in Dublin on his return from Belfast in November 1791 held itself aloof from the Jacobin, Defender and other radical clubs in the capital.[94] The Society also shied from the kind of underground organisation the Belfast leadership was seeking to develop in the north. While societies accepting direction form the Northern Executive restricted their membership to thirty six, in Dublin the United Irish maintained just one society boasting, at its height, 400 members.

The crucial difference at the outset between the Belfast and Dublin societies was that in the very much larger city the United Irish counted representatives of a growing Catholic mercantile and professional class. Among them were prominent members of the Catholic Committee (of which Tone was then organising secretary), including its chairman John Keogh.[95]

Announcing that there were paid informers in their midst, in January 1794 Neilson had tried to press the Belfast system upon his Dublin comrades. They should coordinate and transact all their business through a twelve-member committee. His proposal was rejected on the grounds that "the United Irishmen, as a legal, constitutional reform movement, were loath to engage in any activity which could not bear the scrutiny of the public or the Castle".[96]

Keogh's dismissal of Edmund Burke's son, Richard Burke, as Committee secretary in 1792, and his replacement by Tone, a known democrat still suggested a political shift. The British Prime Minister Pitt was already canvassing support for a union of Ireland and Great Britain in which Catholics could be freely—because securely—admitted to Parliament.[97] London might yet be an ally in relieving Catholics of the last of the Penal Law restrictions, but it would be as a permanent minority in the enlarged Kingdom, not as a national majority in Ireland. Even that prospect was uncertain. Although tempered since the Gordon Riots, Anti-Popery remained an important strain in English politics. Meanwhile, Drennan recalls, "Catholics were being driven to despair" and were prepared to "go to extremities" rather than again be denied political equality.[98]

In April, matters were brought to a head by the arrest of the Reverend William Jackson. An agent of the French Committee of Public Safety, Jackson had been having meetings with Tone in the prison cell of Archibald Hamilton Rowan. Rowan, who had been serving time for distributing Drennan's seditious appeal to Volunteers, managed to flee the country. Whether because of his association with the Catholic Committee or his family's connections, Tone was allowed to go into American exile. Thomas Troy, Catholic Archbishop of Dublin and Papal legate, threatened excommunication for any Catholic who took the United Irish oath and warned his flock to avoid the "fascinating illusions" of French principles.[99] Catholic gentry and clergy withdrew from the Catholic Committee and the United Irish Society was proscribed.[100]

Former and potential United Irish members regrouped with previously neglected lower-rank Jacobins and Defenders in a series of "ephemeral organisation" (The Philanthropic Society, the Huguenots, the Illuminati, the Druids' Lodges...) used as a cover for their activities in Dublin, but also to spread the movement into the provinces. The authorities came down heavily on the Belfast radicals, with Castlereagh personally supervising the arrests of Neilson, Russell and Charles Teeling in September 1796.[101] But early in 1797 their organising vision prevailed. All the various republican clubs and cover lodges, and much of Defender network, were formally marshalled in a local and provincial delegate-structure under a national United Irish executive in Dublin[102] Among others, the directorate included Thomas Addis Emmet; Richard McCormick, Tone's replacement as secretary to the Catholic Committee; and two disillusioned parliamentary patriots: the future Napoleonic general Arthur O'Connor and the popular Lord Edward Fitzgerald.

"Unionising" in Britain

United Scotsmen

The war with France was also used to crush reformers in Great Britain, costing the United Irishmen the liberty of friends and allies. In 1793 in Edinburgh, Thomas Muir, whom Rowan and Drennan had feted in Dublin, with three other of his Friends of the People were sentenced to transportation to Botany Bay (Australia). The judge seized on Muir's connection to the "ferocious" Mr. Rowan (Rowan had challenged Robert Dundas, the Lord Advocate of Scotland, to a duel) and on the United Irishmen papers found in his possession.[103]

There followed in England the 1794 Treason Trials and, when these collapsed, the 1795 Treason Act and Seditious Meetings Act. The measures were directed at the activities of the London Corresponding Society and other radical groups among whom, as ambassadors for the Irish cause, Roger O'Connor and Jane Greg had been cultivating understanding and support for the Irish cause.[104][105]

In the face of the repression, sections of the democratic movement in both Scotland and in England began to regard universal suffrage and annual parliaments as a cause for physical force. Political tours by United Irishmen in the winter of 1796–7 helped to promote such thinking and foster an interest in establishing societies on the new model Irish example.[106]

When the authorities first became aware of the United Scotsmen early in 1797, in their view it was as little more than a Scottish branch of the United Irishmen. The Resolutions and Constitution of the United Scotsmen (1797) was "a verbatim copy of the constitutional document of the United Irishmen, apart from the substitution of the words 'North Britain' for 'Irishmen'". At their height, before meeting at the end of year systematic repression, the United Scotsmen counted upwards of 10,000 members, the backbone formed (as had increasingly been the case for Belfast and Dublin societies) by artisan journeymen and weavers.[107]

United Englishmen, United Britons

With the encouragement of Irish and Scottish visitors, the manufacturing districts of northern England saw the first cells of the United Englishmen formed in late 1796. Their clandestine proceedings, oath taking, and advocacy of physical force "mirrored that of their Irish inspirators", and they followed the Irish Northern Executive-promoted branch system (membership set at a minimum of fifteen and splitting when reaching thirty or thirty-six).[108]

Describing himself as an emissary of the United Irish executive, the Catholic priest James Coigly (a veteran of unionising activities during the Armagh Disturbances)[109] worked from Manchester with James Dixon, a cotton spinner from Belfast, to spread the United system to Stockport, Bolton, Warrington and Birmingham.[110] In London Coigly conferred with those Irishmen who had hastened the radicalisation of the London Corresponding Society: among them United Irishman Edward Despard, brothers Benjamin and John Binns, and LCS president Alexander Galloway. Meetings were held at which delegates from London, Scotland and the regions committed themselves "to overthrow the present Government, and to join the French as soon as they made a landing in England".[109]

At the end of February 1798, as he was about to embark on a return mission to Paris, Coigly was arrested carrying an address to the French Directory from the United Britons. While its suggestion of a mass movement primed for insurrection was scarcely credible, it was deemed sufficient proof of the intention to induce a French invasion. The united movement was broken up by internment and Coigly was hanged.[109]

After the suppression of the insurrection in Ireland, in February 1803 Despard, who had remained in communication with Robert Emmett, followed Coigly to the gallows. Despard was convicted of conspiring with the remnants of the united network in London (disaffected soldiers and labourers, many of them Irish) to assassinate the King and seize the Tower of London.[111]

Alleged role in the 1797 naval mutinies

In justifying the suspension of habeas corpus the authorities were more than ready to see the hand not only of English radicals but also, in the large Irish contingent among the sailors, of United Irishmen in the Spithead and Nore mutinies of April and May 1797.[112] The United Irish were reportedly behind the resolution of the Nore mutineers to hand the fleet over to the French "as the only government that understands the Rights of Man".[113] Much was made of Valentine Joyce, a leader at Spithead, described by Edmund Burke as a "seditious Belfast clubist",[114] (and recorded by R. R. Madden as having been an Irish Volunteer in 1778).[115]

That the Valentine Joyce in question was Irish and a republican has been disputed,[116] and while that "rebellious paper, the Northern Star" may have circulated as reported among the mutineers,[117] no evidence has emerged of a concerted United Irish plot to subvert the fleet. In Ireland there was talk of seizing British warships as part of a general insurrection, but it was only after the Spithead and Nore mutinies that United Irishmen awoke to the effectiveness of formulating sedition within the Royal Navy".[118]

There were a number of mutinies instigated by Irish sailors in 1798 including aboard the HMS Defiance where the court martial took evidence of oaths of allegiance to the United Irishmen and sentenced eleven men to hang.[119][120]

1798 Rebellion

With, or without, the French

In February 1798 a return prepared by Fitzgerald for the national executive reported the number of sworn United Irishmen at their command as 269,896. Figures may have been inflated,[121] and it is certain that, in the event of their heeding the call, most would have been able to arm themselves only with simple pikes (of these the authorities, in the year 1797, had seized 70,630 compared to just 4,183 blunderbusses and 225 musket barrels).[122] Released in December after more than a year in Kilmainham, McCracken was undaunted, but most of the leadership were with Tone in believing French assistance essential.

This Tone almost succeeded in securing. On 15 December 1796, he arrived off Bantry Bay with a fleet carrying about 14,450 men, and a large supply of war material, under the command of Louis Lazare Hoche. A gale prevented a landing. Hoche's unexpected death on his return to France was a blow to what had been Tone's adept handling of the politics of the French Directory. With the forces (and ambition) that might have allowed a second attempt upon Ireland, Hoche's rival, Napoleon, sailed in May 1798 for Egypt.

Bantry Bay, nonetheless, had made real the prospect of French intervention. From December to May 1797 membership in Ulster alone increased fourfold, reaching 117,917.[123] The government responded with an Insurrection Act, allowing the Lord Lieutenant to govern by martial decree.

The United Irishmen had their first martyr in William Orr. Charged in April with administering a United Irish oath to a soldier, Orr was hanged in October. The Reverend William Porter, who had been enraging Viscount Castlereagh with a popular satire of the County Down landed-interest Billy Bluff,[124] was in time to prove a second. In February he asked his congregation neighbouring Castlereagh's family demesne at Mount Stewart (then under armed guard, and with tenants withholding rent), why Ireland was at war: "it is in consequence of our connection with England". A French invasion threatened only the government, not the people.[125] Porter was hung outside his Church in July 1798.

Orr's arrest signalled the onset of General Lake's "dragooning of Ulster",[126] hastened in some districts demonstrations of solidarity with those taken prisoner. When Orr was arrested in Antrim, the Northern Star reported between five and six hundred of his neighbours assembled and brought in his entire harvest. Fifteen hundred people dug Samuel Nielson's potatoes in seven minutes. Such "hasty diggings" (traditionally accorded by families visited by misfortune) could be occasion for United Irish mustering, drilling and training.[127]

By the end of 1797 Lake was turning his attention to disarming Leinster and Munster. His troops' reputation for half-hanging, pitch-capping and other interrogative refinements travelled before them.[128]

In March 1798, the national executive and its papers were seized in Dublin. Faced with the breaking-up of their entire system, the few leaders at large in the capital, joined by Neilson who had been released in ill health from Kilmainham Prison, resolved, with or without the French, on a general uprising for 23 May. Betrayed by informants, Fitzgerald was mortally wounded on the 19th, and on the 23rd Neilson was re-arrested. Tens of thousands heeded the call, but in what proved to be a series of uncoordinated local uprisings.[129]

The South

Some historians conclude that what connects the United Irishmen to most widespread and sustained of the uprisings in 1798 are "accidents of time and place, rather than any real community of interest".[130] Daniel O'Connell, who abhorred the rebellion, may have been artful in proposing that there had been no United Irishmen in Wexford. But his view that the uprising in Wexford had been "forced forward by the establishment of Orange lodges and the whipping and torturing and things of that kind" was to be widely accepted[131]

The Wexford Rebellion broke not in the securely Catholic south of the county, where there had been some political organisation, but in the sectarian-divided north and centre which had seen previous agrarian disturbances.[132] The trigger on 26 May 1798 was the arrival of the notorious North Cork Militia.[133] The insurgents swept south through Wexford Town meeting their first reversal at New Ross on 30 May. There followed the massacre of loyalist hostages at Scullabogue and, after a Committee of Public Safety was swept aside, at Wexford Bridge. A "striking resemblance" has been proposed to the 1792 September massacre in Paris",[134] and it is noted that there were a small number of Catholics among the loyalists killed, and of Protestants among the rebels present.[135] But for loyalists the sectarian nature of the outrages was unquestioned and was used to great effect in the north to secure defections from the republican cause. Much was made of the report that a Catholic priest, Father John Murphy, had commanded the rebels in their initial victory over the North Cork Militia at Oulart Hill.[136]

After a bombardment and rout of upwards of 20,000 rebels upon Vinegar Hill on 21 June remnants of the "Republic of Wexford" marched north through the Midlands—the counties thought best organised by the Executive—but few joined them. Those in the region who had turned out on 23 May had already been dispersed. On 20 July, rejoining insurgents in Kildare, the few hundred remaining Wexford men surrendered. All but their leaders benefited from an amnesty intended by the new Lord Lieutenant, Charles Cornwallis to flush out remaining resistance. The law was pushed through the Irish Parliament by the Chancellor, Lord Clare. A staunch defender of the Ascendancy, Clare was determined to separate Catholics from the greater enemy, "Godless Jacobinism."[137]

Contending with marauding bands of rebel survivors (the Babes in the Wood and the Corcoran gang), Wexford did not see martial law lifted until 1806. In continued expectation of the French, and kept informed by Jemmy Hope of Robert Emmet's plans for a renewed uprising, Michael Dwyer sustained a guerrilla resistance in the Wicklow mountains until the end of 1803.

The North

.jpg.webp)

The northern executive had not responded to the call on 23 May. The senior Dublin Castle secretary, Edward Cooke, could write: "The quiet of the North is to me unaccountable; but I feel that the Popish tinge of the rebellion, and the treatment of France to Switzerland [the Protestant Cantons were resisting occupation] and America [the Quasi naval war], has really done much, and, in addition to the army, the force of Orange yeomanry is really formidable."[138] In response to the claim that "in Ulster there are 50,000 men with arms in their hands, ready to receive the French," the Westiminster Commons was assured that while "almost all Presbyterians... were attached to the popular, or, what has been called, the republican branch of the constitution, they are not to be confounded with Jacobins or banditti".[139]

When Robert Simms, despairing of French aid, resigned his United Irish command in Antrim on 1 June, McCracken seized the initiative. He proclaimed the First Year of Liberty on 6 June. There were widespread local musters but before they could coordinate, most were burying their arms and returning to their farms and workplaces. The issue had been decided by the following evening. McCracken, commanding a body of four to six thousand, failed, with heavy losses, to seize Antrim Town.

In Down, Dickson, who had stood in for Russell, was arrested with all his "colonels". Under the command of a young Lisburn draper, Henry Monro, there was a rising on 9 June. Following a successful skirmish at Saintfield several thousand marched on Ballynahinch where they were completely routed.

Shortly before the Battle of Ballynahinch on the 12th, The Defenders of County Down had withdrawn. John Magennis, their county "Grand Master", had been dismayed by Munro's discounting of a night attack upon the carousing soldiery as "unfair".[140] Defenders had been present at Antrim, but in the march upon the town tensions with the Presbyterian United Irish may have caused some desertions and a delay in McCracken's planned attack.[141]

Confident of a being able exploit tensions between Presbyterians and Catholics, the government not only amnestied the rebel rank-and-file it recruited them for the Yeomanry. On 1 July 1798 in Belfast, the birthplace of the United Irishmen movement, it is said that every man was wearing the Yeomanry's red coat. As he enlisted former United Irishmen into his Portglenone Yeomanry Corps, Anglican clergyman Edward Hudson claimed that "the brotherhood of affection is over".[142]

On the eve of following his leader to the gallows, one of McCracken's lieutenants, James Dickey, is reported by Henry Joy (a hostile witness) as saying: "the Presbyterians of the north perceived too late that if they had succeeded in their designs, they would ultimately have had to contend with the Roman Catholics".[143]

The West

On 22 August 1798, 1,100 French landed at Killala in County Mayo. After prevailing in a first engagement, the Races of Castlebar, but unable to make timely contact with a new rising in Longford and Meath, General Humbert surrendered his forces on 8 September. The last action of the rebellion was a slaughter of half-armed peasants outside Kilala on the 23rd.

On 12 October, the second French expedition was intercepted off the coast of Donegal, and Tone taken captive. Regretting nothing done "to raise three million of my countrymen to the ranks of citizen," and lamenting only those "atrocities committed on both sides" during his exile,[144] Tone on the eve of execution took his own life.

The disputed legacy

It was not the fulfilment of their hopes, but some United Irishmen sought vindication in the Acts of Union that in 1801 abolished the parliament in Dublin and brought Ireland directly under the Crown in Westminster.[145] Archibald Hamilton Rowan hailed "the downfall of one of the most corrupt assembles that ever existed", and predicted that the new United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland would see "the wreck" of the old Ascendancy.[146]

Drennan was at first defiant, urging Irishmen to enter into a "Solemn League and Covenant [to] maintain their country". But later, in the hope that Westminster might in time realise the original aim of his conspiracy--"a full, free and frequent representation of the people"—he seemed reconciled.[147] "What", he reasoned, "is a country justly considered, but a free constitution"?[148]

In his last years, in the 1840s, Jemmy Hope, who had survived both the Battle of Antrim and his attempt with Thomas Russell to raise the North in support of Robert Emmet's plans for a new insurrection in 1803, chaired meetings of the Repeal Association.[149] Hope had his doubts about the nature of the movement Daniel O'Connell launched in the wake of Catholic Emancipation in 1829 to reverse the Acts of Union and to restore the Kingdom of Ireland under the Constitution of 1782. The Presbyterian districts in the north in which he believed "the republican spirit" had run strongest were never again to support an Irish parliament.

In 1799, in Philadelphia, Thomas Ledlie Birch published his Letter from An Irish Emigrant (1799) which maintained that the United Irish had been "goaded" into insurrection by "rapines, burnings, rapes, murders, and other sheddings of blood".[150] But, in Ireland the first public rehabilitation came in 1831 with The Life and Death of Lord Edward Fitzgerald (1831), described by the author, Ireland's national bard,[151] Thomas Moore as a "justification of the men of '98--the ultimi Romanorum of our country".[152] In 1832 Moore declined a voter petition to stand as a Repeal candidate. He could not pretend with O'Connell that the consequence of Repeal would be less than a real separation from Great Britain, something possible only if Catholics were again "joined by dissenters".[153]

In breaking with O'Connell, Young Irelanders proposed to forge this renewed unity in the struggle for tenant rights and land ownership. Gavan Duffy recalled from his youth a Quaker neighbour who had been a United Irishman and had laughed at the idea that the issue was kings and governments. What mattered was the land from which the people got their bread.[154] Instead of indulging "Gallic passions" and singing the Marseillaise, what the men of '98 should have borrowed from the French was "their sagacious idea of bundling the landlords out of doors and putting tenants in their shoes".[155]

For O'Connell, who believed Dublin Castle had deliberately fomented the rebellion as a pretext for abolishing the Irish parliament,[156] unionist sentiment in the north was simply the product of continued Protestant privilege. Were this abolished with the repeal of the Union, "the Protestant community would with little delay melt into the overwhelming majority of the Irish nation".[157] For nationalists, it remained the "sad irony" of 1798 that by a system of often marginal advantages "the descendants of the republican rebels" were "persuaded" to regard "the 'connection with England' as the guarantee of [their] dignity and rights."[158]

Focused on breaking "the connection with England", Unionists argued that Repealers, Home-Rulers and Republicans misrepresented the true object of the United Irishmen. There was, they insisted, no irony and no paradox in descendants of the United Irish entering a Solemn League of Covenant to maintain their country as the United Kingdom. Had their forefathers been offered a Union under the constitution as it later developed there would have been "no rebellion": "Catholic Emancipation, a Reformed Parliament, a responsible Executive and equal laws for the whole Irish people—these", they maintain, were "the real objects of the United Irishmen".[159]

Noting that "the United Irishmen were, after all, anything but united", a major history of the movement observes that "the legacy of the United Irishmen, however interpreted, has proved as divisive for later generations as the practice of this so-called union did in the 1790s".[160] Writing on the 200th anniversary of the uprising, the historian John A. Murphy, suggests that what can be commemorated—other differences aside—is "the first time entrance of the plain people on the stage of Irish history." The United Irishmen had "promoted egalitarianism and the smashing of deference." After the defeat of their local uprising in June 1798 (the only one in Munster where local Defenderism, the "Rightboys", had been broken a decade before)[161] the Clonakilty Catholics were harangued in their chapel by Rev. Horace Townsend, chief magistrate and Protestant vicar.

Reflect with remorse and repentance on the wicked and sanguinary designs for which you forged so many abominable pikes... Surely you are not foolish enough to think that society could exist without landlords, without magistrates, without rulers... Be persuaded that it is quite out of the sphere of country farmers and labourers to set up as politicians, reformers, and law makers...

What Townsend and the Ascendancy feared most of all were "the manifestations of an incipient Irish democracy". "In the long run," concludes Murphy, "the emergence of such a democracy, rudimentary and inchoate, was the most significant legacy" of the United Irishmen.[162]

See also

Members

- William Aylmer

- Riocard Bairéad

- Thomas Ledlie Birch

- Harman Blennerhassett

- Oliver Bond

- Myles Byrne

- Thomas Cloney

- John Henry Colclough

- Father James Coigly

- William Corbet

- James Corcoran

- Edward Crosbie

- George Cummins

- James Dempsey

- Edward Despard

- James Dickey

- William Steel Dickson

- William Drennan

- William Duckett

- Michael Dwyer

- Robert Emmet

- Thomas Addis Emmet

- Peter Finnerty

- Lord Edward FitzGerald

- Cornelius Grogan

- Bagenal Harvey

- Henry Haslett

- Joseph Holt

- James "Jemmy" Hope

- William Jackson

- Father Mogue Kearns

- John Kelly

- John Keogh

- Matthew Keogh

- Richard Kirwan

- Valentine Lawless

- Thomas McCabe

- Roddy McCorley

- Henry Joy McCracken

- Gilbert McIlveen

- Leonard McNally (informer)

- William James MacNeven

- Samuel McTier

- Edward John Newell (informer)

- Henry Munro

- Thomas Muir, (honorary member)[163]

- Samuel Neilson

- Arthur O'Connor

- Roger O'Connor

- James Orr

- William Orr

- Thomas Paine, honorary member[164]

- Anthony Perry

- Archibald Hamilton Rowan

- Thomas Russell

- William Sampson

- The Sheares Brothers

- Robert Simms

- Whitley Stokes

- James Napper Tandy

- Bartholomew Teeling

- Charles Hamilton Teeling

- William Tennant

- Theobald Wolfe Tone

- David Bailie Warden

Women associated

Fictional Members

References

- "Terminology". An Sionnach Fionn.

- Joy, Henry (1817). Historical Collections Relative to the Town of Belfast. Belfast: George Gerwick. pp. 358–359. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Courtney, Roger (2013). Dissenting Voices: Rediscovering the Irish Progressive Presbyterian Tradition. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation. p. 79. ISBN 9781909556065.

- O'Regan, Raymond (2010). Hidden Belfast. Cork: Mercier Press. pp. 60–63. ISBN 9781856356831.

- Holmes, Andrew (December 2008). "Presbyterians and Science in the North of Ireland before 1874". The British Journal for the History of Science. 41 (4): 545. doi:10.1017/S0007087408001234. JSTOR 30165751. PMID 19391418. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Smyth, Jim (2012). "Wolfe Tone's Library: The United Irishmen and 'Enlightenment'". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 45 (3): 425. doi:10.1353/ecs.2012.0023. S2CID 146389991.

- Fiering, Norman (1981). Moral Philosophy at Seventeenth-Century Harvard: A Discipline in Transition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 199. ISBN 9780807814598.

- Fleischacker, Samuel (2003). "The impact on America: Scottish philosophy and the American founding". In Broadie, Alexander (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Scottish Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 320. ISBN 9780511998638. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- McBride, Ian (1993). "The School of Virtue: Francis Hutcheson, Irish Presbyterians and the Scottish Enlightenment". In Boyce, George; Eccleshall, Robert; Geoghegan, Vincent (eds.). Political Thought in Ireland Since the Seventeenth Century. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. pp. 79–84. ISBN 0415013542.

- Drennan, William (1991). "Intended Defence on a Trial for Sedition, in the Year 1794". In Larkin, John (ed.). The Trial of William Drennan. Dublin: Academic Press. p. Appendix 128. ISBN 9780716524571.

- Altholz, Josef (2000). Selected Documents in Irish History. New York: M E Sharpe. p. 69. ISBN 0415127769. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Bardon, Jonathan (1982). Belfast: An Illustrated History. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. p. 47. ISBN 0856402729. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- Madden, Richard (1843). The United Irishmen, Their Lives and Times (30 May 2020 ed.). Belfast: J. Madden & Company. p. 179.

- Berresford Ellis, Peter (1985). A History of the Irish Working Class. Pluto. pp. 63–64. ISBN 0-7453-0009-X.

- F.X. Martin, T.W. Moody (1980). The Course of Irish History. Mercier Press. pp. 232–233. ISBN 1-85635-108-4.

- Bardon, Jonathan (2008). A History of Ireland in 250 Episodes. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. pp. 286–288. ISBN 9780717146499.

- William Theobald Wolfe Tone, ed. (1826). Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, vol. I. Washington D.C.: Gales and Seaton. p. 141.

- Bardon (1982), pp. 52–53

- William Bruce and Henry Joy, ed. (1794). Belfast politics: or, A collection of the debates, resolutions, and other proceedings of that town in the years 1792, and 1793. Belfast: H. Joy & Co. p. 67.

- News Letter, Belfast, 13 February 1817:

- William Bruce and Henry Joy, ed. (1794). Belfast politics: or, A collection of the debates, resolutions, and other proceedings of that town in the years 1792, and 1793. Belfast: H. Joy & Co. p. 242.

- "Category Archives: William Drennan". assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. February 2020. pp. 15–16. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Altholz, Josef L. (2000). Selected Documents in Irish History. New York: M E Sharpe. p. 70. ISBN 0415127769.

- William Theobald Wolfe Tone, ed. (1826). Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, vol. I. Washington D.C.: Gales and Seaton. p. 149.

- Theobald Wolfe Tone (1791). An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland. Belfast: H. Joy & Co.

- Boyd, Andrew (2001). Republicanism and Loyalty in Ireland. Belfast: Donaldson Archives. pp. 10–11.

- William Theobald Wolfe Tone, ed. (1826). Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, vol. 2. Washington D.C.: Gales and Seaton. p. 278.

- William Theobald Wolfe Tone, ed. (1826). Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, vol. 1. Washington D.C.: Gales and Seaton. p. 149.

- Healy, Róisín (2017). Poland in the Irish Nationalist Imagination, 1772–1922: Anti-Colonialism within Europe. Dublin: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 47. ISBN 9783319434308.

- Theobald Wolfe Tone (1791). An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland. Belfast: H. Joy & Co.

- William Bruce and Henry Joy, ed. (1794). Belfast politics: or, A collection of the debates, resolutions, and other proceedings of that town in the years 1792, and 1793. Belfast: H. Joy & Co. pp. 52–65.

- Paterson, T. G. F. (1941), "The County Armagh Volunteers of 1778–1793", Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Third Series, Vol. 4

- From a selection of articles published by Henry Joy in the News Letter, Belfast, 1792–1793, reproduced in Belfast Politics by Henry Joy, United Irish Reprints: No. 4, Athol Books Belfast (1974), pp. 53, 55.

- Thomas Addis Emmet (1807), "Part of an essay towards the history of Ireland" in Willima James MacNeven, Pieces of Irish History, New York, pp. 76–78

- Curtin, Nancy (1985). "The Transformation of the Society of United Irishmen into a mass-based revolutionary organisation, 1794-6". Irish Historical Studies. xxiv (96): 468.

- Martha McTier to Drennan, [March 1795]. Public Records Office Northern Ireland, Drennan Letters T.765/548, cited in Curtin (1985), p. 473

- Courtney, Roger (2013). Dissenting Voices: Rediscovering the Irish Progressive Presbyterian Tradition. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9781909556065.

- Curtin (1985) p. 473

- Curtin pp. 472–473

- William Bruce and Henry Joy, ed. (1794). Belfast Politics: or, A collection of the debates, resolutions, and other proceedings of that town in the years 1792, and 1793. Belfast: H. Joy & Co. p. 114.

- Curtin (1985), p. 471

- Gray, John (1998). The San Culottes of Belfast: The United Irishmen and the Men of No Property. Belfast: Belfast Trades Union Council and the United Irishmen Commemorative Society. pp. 13–18.

- Northern Star, 9 June & 13 June 1792

- Quinn, James (2002). "Thomas Russell, United Irishman". historyireland.com. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Madden, Robert (1900). Antrim and Down in '98 : The Lives of Henry Joy m'Cracken, James Hope, William Putnam m'Cabe, Rev. James Porter, Henry Munro. Glasgow: Cameron, Ferguson & Co. p. 108.

- R.B. McDowell (ed.) (1942), "Select documents—II: United Irish plans of parliamentary reform, 1793" in Irish Historical Society, iii, no.9 (March), pp. 40–41; Douglas to Mehean, 24 January 1794 (Public Records Office, Home Office, 100/51/98-100); cited in Cronin (1985) p. 465

- Quinn, James (1998). "The United Irishmen and Social Reform". Irish Historical Studies. 32 (122): 188–201. doi:10.1017/S0021121400013900. JSTOR 30008258.

- Curtin, Nancy (1985). "The Transformation of the Society of United Irishmen into a mass-based revolutionary organisation, 1794-6". Irish Historical Studies. xxiv (96): 464–492.

- quoted in Madden (1900), p. 149

- Courtney, Roger (2013). Dissenting Voices: Rediscovering the Irish Progressive Presbyterian Tradition. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation. p. 68. ISBN 9781909556065.

- Bew, John (2012). Castlereagh: A Life. London: Quercas. p. 127. ISBN 9780199931590.

- Clemmit, Pamela (2004). "Godwin, Women and the 'Collision of Mind with Mind'". The Wordsworth Circle. 35 (2): 72–76. doi:10.1086/TWC24044969. JSTOR 24044969. S2CID 150518429.

- Catriona Kennedy (2004), What Can Women Give But Tears': Gender, Politics and Irish National Identity in the 1790s (Submitted for the degree of PhD University of York, Department of History), p. 62. http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/10974/1/425459.pdf

- William Bruce and Henry Joy, ed. (1794). Belfast politics: or, A collection of the debates, resolutions, and other proceedings of that town in the years 1792, and 1793. Belfast: H. Joy & Co. pp. 135, 149.

- Whelan, Fergus (2020). May Tyrants Tremble: The Life of William Drennan, 1754–1820. Dublin: Irish Academic Press. pp. 73–75. ISBN 9781788551212.

- National Archives of Ireland, Dublin, Rebellion Papers, 620/20/1. William Drennan, 'Plan of Parliamentary Representation for Ireland'

- McNeill, Mary (1960). The Life and Times of Mary Ann McCracken, 1770–1866. Dublin: Allen Figgis & Co. pp. 126–127.

- Northern Star, 17 October 1776

- Kennedy, pp. 159-160

- National Archives of Ireland, Dublin, Rebellion Papers, 620/30/194. Thomas Whinnery to John Lees, 25 May 1797.

- PRONI, Pelham Manuscripts T755/5, Lake to Pelham, 9 June 1797

- McNeill, Mary (1960). The Life and Times of Mary Ann McCracken, 1770–1866. Dublin: Allen Figgis & Co. p. 127.

- Kennedy, Catriona (September 2004). 'What Can Women Give But Tears' : Gender, Politics and Irish National Identity in the 1790s (PDF). Submitted for the degree of PhD, University of York, Department of History. pp. 69–70. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- Madden, Richard (1843). The United Irishmen, Their Lives and Times. J. Madden & Company. p. 31.

- NAI, Dublin, Rebellion Papers, 620/18/14. Francis Higgins, 29 January 1797.

- Kennedy, p. 158

- NA1, Dublin, Rebellion papers, 620/30/211. 'Left Hand' to Secretary Pelham and Secretary Cooke, 27 May 1797; R. R. Madden, The United Irishmen their Lives and Times (New York, 1916 [184246]), vol.6 p. 18

- Kennedy, p. 168

- Smith, Michelle (23 May 2020). "Remembering the start of the 1798 rebellion through Irish heroine Betsy Gray". Irish Central. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Whelan, Fergus (2015). God-Provoking Democrat: The Remarkable Life of Archibald Hamilton Rowan. Stillorgan, Dublin: New Island. p. 45. ISBN 9781848404601.

- from Jacques-Louis Bougrenet de La Tocnaye, Promenade d’un Français dans l’Irlande, published (in French) in Dublin in 1797, quoted in Denis Ireland (1936), From the Irish Shore: Notes on My Life and Times, Rich & Cowan, London, pp. 114–115

- Curtin (1985), p. 469

- David Rudland, "1798 and Freemasonry", History Ireland, Vol. 6, no. 4 (Winter 1998), Letters. https://www.historyireland.com/the-united-irishmen/1798-and-freemasonry/

- Harland-Jacobs, Jessica (2007). Builders of Empire: Freemasons and British Imperialism, 1717–1927. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 124–126. ISBN 9780807830888.

- Dawson, Kenneth (3 January 2020). "Moment of unite--Irish rebels and Freemasons". Irish News. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- John Lawless, ed. (1816). Belfast Politics: Enlarged, Being a Compendium of the Political History of Ireland for the Last Forty Years. Belfast: D. Lyons. p. 393.

- Jean Agnew, ed. (1998). The Drennan-McTier Letters 1776–1819, Vol. 2. Dublin: The Women's History Project/Irish Manuscripts Commission. p. 502.

- Bardon, Jonathan (1982). Belfast: An Illustrated History. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. p. 60. ISBN 0856402729.

- Courtney, Roger (2013). Dissenting Voices: Rediscovering the Irish Progressive Presbyterian Tradition. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation. p. 135. ISBN 9781909556065.

- Donnelly Jr, James (1980). "Propagating the Cause of the United Irishmen". Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. 69 (273): 5–23, 15. JSTOR 30090237.

- William Theobald Wolfe Tone, ed. (1826). Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, vol. 1. Washington D.C.: Gales and Seaton. p. 127.

- Society of United Irishmen of Dublin: Established November IX. MDCCXCI. "Let the Nation Stand.". Dubiln: Society of the United Irishmen of Dublin. 1794. p. 5.

- Curtin (1985), p. 475

- William Theobald Wolfe Tone, ed. (1826). Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, vol. 2. Washington D.C.: Gales and Seaton. p. 45. ISBN 9781108081948.

- Smyth, Jim (1992). The men of no property: Irish radicals and popular politics in the late eighteenth century. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 9780312075903.

- Curtin, Nancy (1985). "The Transformation of the Society of United Irishmen into a mass-based revolutionary organisation, 1794-6". Irish Historical Studies. xxiv (96): 467–477.

- Foster (1988), 272

- Curtin, Nancy (1985). "The Transformation of the Society of United Irishmen into a mass-based revolutionary organisation, 1794-6". Irish Historical Studies. xxiv (96): 478–479.

- Foster (1988), p. 272

- W. Bro. Larry Conlon. "Freemasonry in Meath and Westmeath". Navan and District Historical Society. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Smyth, Jim (1998). The Men of No Property, Irish Radicals and Popular Politics in the Late Eighteenth Century. London: Macmillan. pp. 118–119. ISBN 9781349266531.

- Charles Teeling (1838), History and Consequences of the Battle of the Diamond, Hodgson, Belfast

- Curtin, Nancy (1985). "The Transformation of the Society of United Irishmen into a mass-based revolutionary organisation, 1794-6". Irish Historical Studies. xxiv (96): 483, 486.

- Murtagh, Timothy (2016). "Hibernian Sans-Culottes? Dublin's Artisans and Radical Politics 1790–1798". La Révolution Française. 11 (11): 2. doi:10.4000/lrf.1643.

- John Keogh (1740–1817) www.ricorso.net

- Curtin (1985), p. 474

- Kelly, James (1987). "The Origins of the Act of Union: An Examination of Unionist Opinion in Britain and Ireland, 1650–1800". Irish Historical Studies. 25:99 (99): 236–263–85. doi:10.1017/S0021121400026614. JSTOR 30008541.

- Smith, Jim (1998). The Men of No Property: Irish Radicals and Popular Politics in the Late Eighteenth Century. London: St Martin's Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780333732564.

- Kennedy, W. Benjamin (December 1984). "Catholics in Ireland and the French Revolution". Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. 84 (3/4): 222. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- AN INSTALMENT OF EMANCIPATION (1790–1793) www.libraryireland.com

- Bew, John (2011). Castlereagh: Enlightenment, War and Tyranny. London: Quercus. pp. 96–98. ISBN 9780857381866.

- Fagan, Patrick (1998). "Infiltration of Dublin Freemason Lodges by United Irishmen and Other Republican Groups". Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an Dá Chultúr. 13: 65–85. JSTOR 30064326.

- Fergus Whelan (2014). God-Provoking Democrat: The Remarkable Life of Archibald Hamilton Rowan. Stillorgan, Dublin: New Island Books. pp. 96–100. ISBN 9781848404601.

- Smith, A.W (1995). "Irish Rebels and English Radicals 1798-1820. Past & Present". JSTOR 650175. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kennedy, Catriona (2004). "'Womanish Epistles?' Martha McTier, Female Epistolarity and Late Eighteenth-Century Irish Radicalism". Women's History Review. 13 (1): 660. doi:10.1080/09612020400200404. S2CID 144607838. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Davis, Michael (2009). "United Englishmen/ United Britons". The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest. Wiley Online Library. The International Encyclopaedia of Revolution and Protest (2009). pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp1500. ISBN 9781405198073. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Davis, Michael (2008). "United Scotsmen". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/95551. Retrieved 10 November 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Davis, Michael. "United Englishmen". OxfordDNB. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Keogh, Dáire (1998). "An Unfortunate Man". 18th–19th - Century History. 6 (2). Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Booth, Alan (1986). "The united Englishmen and Radical Politics in the Industrial North West of England, 1795-1803". International Review of Social History. 31 (3): 271–297. doi:10.1017/S0020859000008221. JSTOR 44582816. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Jay, Mike (2005). The Unfortunate Colonel Despard. Bantam Press.

- Dugan, James (1965). The Great Mutiny. London: the Trinity Press. pp. 420–425. ISBN 9787070012751.

- Cole, G. D. H.; Postgate, Raymond (1945). The Common People, 1746-1938 (Second ed.). London: Methuen & Co. Ltd. p. 162.

- Manwaring, George; Dobree, Bonamy (1935). The Floating Republic: An Account of the Mutinies at Spithead and the Nore in 1797. London: Geoffrey Bles. p. 101.

- Richard Madden (18960), The United Irishmen, Lives and Times. London, The Catholic Publishing and Bookselling Company. p. 29.

- Barnett, Len. "Valentine Joyce--Naval Mutineer of 1797" (PDF). Reality behind a Myth - the life of a Spithead Mutineer of 1797. Barnett Maritime. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- Corbett, Julian (1816). Private Pater of George, Second Earl of Spencer. London: Publication of the Navy Records Society. pp. 119–120.

- Dugan (1965), p. 425

- TNA ADM 1/5346 - Court martial papers

- Featherstone, David (2013). "'We will have equality and liberty in Ireland': The Contested Geographies of Irish Democratic Political Cultures in the 1990s" (PDF). Historical Geography. 41: 128–130. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- Curtin (1985), p. 488

- Baines, Edward (1817). History of the Wars of the French Revolution ..., Volume 1. London: Longman, Herst, Bees, Orme & Brown. p. 225.

- Bew, John (2011). Castlereagh: Enlightenment, War and Tyranny. London: Quercus. p. 107. ISBN 9780857381866.

- Brendan Clifford, ed. (1991). Billy Bluff and the Squire [1796] and Other Writing by Re. James Porter. Belfast: Athol Books. p. 80. ISBN 9780850340457.

- Bew, John (2011). Castlereagh: Enlightenment, War and Tyranny. London: Quercus. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9780857381866.

- Curtin, Nancy J. (2000). "The Magistracy and Counter-Revolution in Ulster, 1795-1798". In Smyth, Jim (ed.). Revolution, Counter-Revolution and Union: Ireland in the 1790s. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 0521661099.

- Clifford, Brendan (1992). Prison Adverts and Potatoe Diggings: Materials from the Public Life of Antrim and Down During the Years of Government Terror Which Led to the Rebellion of 1798. Belfast: Athol Book.

- Bennell, Anthony S. (2004). "Lake, Gerard, first Viscount Lake of Delhi (1744–1808)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1998). The Year of Liberty: The Great Irish Rebellion of 1798 (Special Bicentennial ed.). New York: Times Books. pp. 36–38.

- Beckett (1966), p. 264

- Woods, J.C. (2006). "Historical revision: was O'Connell a United Irishman?". Irish Historical Studies. 35 (138): 173–174. doi:10.1017/S0021121400004879. JSTOR 20547427.

- Ó hÓgartaigh, Margaret (2010). Edward Hay: Historian of 1798. Dublin: The History Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9781845889920.

- Hay, Edward (1803). History of the Insurrection of the County of Wexford, A. D. 1798. Dublin: John Stockdale. p. 57.

- Ó hÓgartaigh (2010), p.44

- Gahan, D. "The Scullabogue Massacre, 1798", History Ireland, v4 (1996), 3

- Swords, L. (1997) Protestant, Catholic, and Dissenter: The Clergy and 1798, Columbia Press, p. 176

- Pakenham, Thomas (1998). The Year of Liberty: The Great Irish Rebellion of 1798 (Special Bicentennial ed.). New York: Times Books. p. 44.

- quoted McNeill (1960), p. 169

- Francis Plowden (1806). An Historical View of the State of Ireland... Vol. IV. Philadelphia: William McLaughlin. p. 254.

- Proudfoot L. (ed.) Down History and Society (Dublin 1997) chapter by Nancy Curtin at p.289. ISBN 0-906602-80-7

- "Author on the hunt for local tales as he pens new book on the Battle of Antrim". Antrim Guardian. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- Blackstock, Alan: A Forgotten Army: The Irish Yeomanry. History Ireland, Vol 4. 1996

- Joy, Henry (1817). Historical collections relative to the town of Belfast: from the earliest period to the Union with Great Britain). Belfast: George Gerwick. pp. xi.

- Harwood, Philip (1844). History of the Irish Rebellion. London: Chapman & Elcoate. p. 235.