EgyptAir Flight 804

EgyptAir Flight 804 was a regularly scheduled international passenger flight from Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport to Cairo International Airport, operated by EgyptAir. On 19 May 2016 at 02:33 Egypt Standard Time (UTC+2), the Airbus A320 crashed into the Mediterranean Sea, killing all 56 passengers, 3 security personnel, and 7 crew members on board.

SU-GCC, the aircraft involved, seen in January 2016 | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 19 May 2016 |

| Summary | Under investigation, probable in-flight fire |

| Site | Mediterranean Sea 33.6757°N 28.7924°E[lower-alpha 1][1] |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Airbus A320-232 |

| Operator | EgyptAir |

| IATA flight No. | MS804 |

| ICAO flight No. | MSR804 |

| Call sign | Egypt Air 804 |

| Registration | SU-GCC |

| Flight origin | Charles de Gaulle Airport, Paris, France |

| Destination | Cairo International Airport, Cairo, Egypt |

| Occupants | 66 |

| Passengers | 56 |

| Crew | 10 |

| Fatalities | 66 |

| Survivors | 0 |

No mayday call was received by air traffic control, although signals that smoke had been detected in one of the aircraft's lavatories and in the avionics bay were automatically transmitted via ACARS shortly before the aircraft disappeared from radar. The last communications from the aircraft prior to its submersion were two transmissions from its emergency locator transmitter that were received by the International Cospas-Sarsat Programme. The cause of the disaster is under investigation.

Debris from the aircraft was found in the Mediterranean Sea approximately 290 km (180 mi) north of Alexandria. Nearly four weeks after the crash, several main sections of wreckage were identified on the seabed, and both flight recorders were recovered in a multinational search and recovery operation. On 29 June, Egyptian officials announced that the flight data recorder data indicated smoke in the aircraft, and that soot plus damage from high temperatures was found on some of the wreckage from the front section of the aircraft.[2]

In August 2016, French foreign minister Jean-Marc Ayrault criticized the fact that no further explanation for the reasons behind the crash had been given.[3] In December 2016, Egyptian officials said traces of explosives were found on the bodies[4] but in May 2017, French officials denied that.[5] On 6 July 2018, France's BEA stated that the most likely hypothesis was a fire in the cockpit that spread rapidly.[6]

A manslaughter investigation was started in France in June 2016; in April 2019 a report commissioned as part of the investigation stated the aircraft was not airworthy and should have never taken-off: recurring defects had not been reported by the crews, including alerts reporting potential fire hazards.

Aircraft

The aircraft involved was an Airbus A320-232,[lower-alpha 2] registration SU-GCC, MSN 2088.[7] It made its first flight on 25 July 2003, and was delivered to EgyptAir on 3 November 2003.[8] The aircraft was powered by two IAE V2527-A5 engines.

The flight was the aircraft's fifth that day, having flown from Asmara International Airport, Eritrea, to Cairo; then from Cairo to Tunis–Carthage International Airport, Tunisia, and back. The last completed flight of the aircraft, before its ultimate crash, was Flight 803 to Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport.[9]

Flight

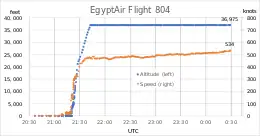

The aircraft departed for Cairo International Airport from Charles de Gaulle Airport on 18 May 2016 at 23:09 (all times refer to UTC+2, used in France and Egypt at the time).[10][11] It disappeared from radar while flying at flight level 370 (about 37,000 ft (11,300 m) in altitude) in clear weather, 280 km (170 mi; 150 nmi) north of the Egyptian coast,[12] and about the same distance from Kastellorizo, over the eastern Mediterranean on 19 May at 02:30.[13][14][15] The aircraft crashed into the sea around 2:33, when the last ACARS message was sent. The flight had lasted 3 hours 25 minutes.[16]

The aircraft was due to land at 03:05. It was originally reported that a distress signal from emergency devices was detected by the Egyptian military at 04:26, two hours after the last radar contact; officials later retracted this statement.[17]

On the day of the crash Panos Kammenos, the Greek defence minister, noted the aircraft changed heading 90 degrees to the left, then turned 360 degrees to the right while it dropped from Flight Level 370 to 15,000 feet (4,600 m).[18][19] This information was rejected on 23 May by an Egyptian official from the National Air Navigation Services Company, who stated that there was no change in altitude and no unusual movement before the aircraft disappeared from radar.[20] It is possible that Egyptian radars were unable to track the aircraft as accurately as Greek radars due to their distance from the aircraft.[21] On 14 June, Egyptian authorities confirmed the statements made by Greek officials.[22] According to a former investigator, the initial left turn could have exceeded computer-controlled flight protections, and might also have come close to or exceeded the structural design limits of the aircraft.[22]

Passengers and crew

The 66 passengers and crew all died. They collectively held citizenship in 13 different countries.

| Citizenship | No. |

|---|---|

| Algeria | 1 |

| Belgium | 1 |

| Canada[24][lower-alpha 3] | 1 |

| Chad | 1 |

| Egypt | 30 |

| France | 15 |

| Iraq | 2 |

| Kuwait | 1 |

| Portugal | 1 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 |

| Sudan | 1 |

| United Kingdom[lower-alpha 4] | 1 |

| Crew | 10 |

| Some passengers had multiple citizenship. Counts are based on preliminary data. | |

Fifty-six passengers from twelve different countries were on board.[23] Three passengers were reported to be children, including two infants.[28] Some of the passengers held multiple citizenship.[27]

The crew of ten consisted of two pilots, five flight attendants, and three security personnel.[29] According to EgyptAir, captain Mohammed Shoqeir had 6,275 hours of flying experience, including 2,101 hours on the A320, while first officer Mohamed Assem had 2,766 hours.[30]

Search and recovery efforts

Initial efforts

The Egyptian Civil Aviation Ministry confirmed that search and rescue teams were deployed to look for the missing aircraft. Search efforts were carried out in coordination with Greek authorities. A spokesman for the Egyptian Civil Aviation Agency stated that the aircraft most likely crashed into the sea.[31] Greece and France sent aircraft and naval ships to the area to participate in search and rescue efforts.[32][33][34] The United Kingdom sent a naval ship, while the United States sent a naval aircraft.[35][36]

Search area

On 20 May, units of the Egyptian Navy and Air Force discovered debris, body parts, passengers' belongings, luggage, and aircraft seats at the crash site, 290 km (180 mi; 160 nmi) off the coast of Alexandria, Egypt. Two fields of debris were spotted from the air between 20 May at dusk and 23 May at dawn; one of them was 3 nmi (3.5 mi; 5.6 km) in radius.[37] At this time, the searched area measured nearly 14,000 km2 (5,400 sq mi),[37] with the sea being 2,440 to 3,050 metres (8,000 to 10,000 ft) deep there.[38]

| External image | |

|---|---|

The European Space Agency (ESA) announced on 20 May that it had possibly detected a 2 km-long fuel slick at 33°32′N 29°13′E, about 40 kilometres (25 mi) southeast of the last known location of Flight 804, on imagery captured by its Sentinel-1A satellite at 16:00 UTC on 19 May.[39]

On 26 May, it was reported that signals from the aircraft's emergency locator transmitter had been detected by satellite, which narrowed the area where the main wreckage was likely to be located on the seabed to within a radius of 5 kilometres (3 mi). An emergency locator transmitter usually activates at impact to send a radio distress signal; this is not the signal from an underwater locator beacon (ULB) attached to a flight recorder, which is an ultrasonic pulse.[40][41][42] The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration confirmed that the emergency locator transmitter signal was received by satellites minutes after the airliner disappeared from radar.[43] A "distress signal" received two hours after the disappearance of the aircraft, possibly originating from the emergency locator transmitter, had been reported already on 19 May; this report was denied by EgyptAir.[44][45]

At the beginning of June, after ultrasonic pulses from a ULB of one of the flight recorders had been detected, a "priority search area" 2 kilometres (1 mi) in radius[46] was established.[47][48]

The John Lethbridge,[49] a vessel belonging to Deep Ocean Search,[47] equipped with a remotely operated underwater vehicle that can detect signals in depths of up to 6,000 metres (20,000 ft), and map the seabed, was contracted by Egyptian authorities.[50][51] Capable of retrieving the flight recorders from the seabed, it left the Irish Sea on 28 May and, at that time, it was expected to arrive at the search area around 9 June, after stopping in the Egyptian Port of Alexandria to board Egyptian and French investigators.[52] The vessel was delayed, arriving in Alexandria on 9 June[53] and at the search area some time on or before 13 June.[22] On 15 June, Egyptian authorities announced that searchers on board the John Lethbridge had identified several main sections of wreckage on the seabed.[54] On 9 July, the Egyptian government reported it was extending the John Lethbridge's stay at the crash site, to 18 July.[55] The John Lethbridge concluded its mission to recover human remains and returned to the port of Alexandria on 16 July. On arrival, the recovered remains were transferred from the John Lethbridge to Egypt's Department of Forensic Medicine in Cairo for DNA analysis and processing.[56]

Flight recorders

On 22 May, an Egyptian remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV), owned by the country's Oil Ministry, was deployed to join the search for the missing aircraft. President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi stated that the ROV can operate at a depth of 3,000 metres (9,840 ft).[57][58][59] According to Egypt's chief investigator with the Civil Aviation Ministry, Ayman al-Moqadem, the ROV cannot detect signals from flight recorders.[60]

A French Navy D'Estienne d'Orves-class aviso ship, the Enseigne de vaisseau Jacoubet, equipped with sonar able to detect the underwater "pings" emitted by the ULBs of the flight recorders, arrived at the possible crash site on 23 May.[37][61] The French ship can deploy an ROV that can dive up to 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) and that is able to detect signals from ULBs but with limited depth range.[62]

On 26 May, Italian and French companies capable of executing deep-sea searches, including ALSEAMAR and the Mauritius-based Deep Ocean Search, were asked by Egypt to help locate the flight recorders.[63]

A more specialized French Navy ship, the oceanographic research ship Laplace, left the Corsican port of Porto-Vecchio for the search area on 27 May, according to French aircraft accident investigation body the Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la Sécurité de l'Aviation Civile (BEA). The vessel can deploy three towed Alseamar hydrophone arrays that are designed to detect a ULB from a distance of up to nearly 4 kilometres (2 mi).[64][65] On 1 June, the Egyptian Civil Aviation Ministry reported that "pings" from a ULB of one of the flight recorders had been detected by the Laplace.[47][48] This was confirmed by the BEA whose spokesperson announced the establishment of a "priority search area".[48]

The survey ship John Lethbridge was at the search area by 13 June.[22] The ULBs, which were activated on 19 May, are designed to last for at least 30 days;[22] the Egyptian board of inquiry said the signals would continue until 24 June.[53] On 16 June, Egyptian authorities announced that the searchers on the John Lethbridge had found the cockpit voice recorder (CVR), damaged, at a depth of 13,000 feet (4,000 m). The memory unit was retrieved intact and sent to Cairo[66] for investigation, following the transfer of the CVR to Egyptian civil aviation officials in Alexandria.[67] The next day it was announced that the John Lethbridge had been used to retrieve, in several pieces, the second flight recorder—the flight data recorder (FDR).[68] The memory unit was recovered from the damaged flight data recorder[69] but an Egyptian official stated that the flight recorders require extensive repair before they could be properly analyzed and accessed.[66]

On 19 June, Egypt's Aircraft Accident Investigation Committee announced that they, with the assistance of the Egyptian Armed Forces, had completed the drying procedure of the intact memory modules and started electrical testing of the memory modules from both the cockpit voice recorder and the flight data recorder.[70]

On 21 June, officials involved in the investigation disclosed that the memory chips from both recorders were damaged.[71][72] After the initial attempts to download data from both recorders failed,[73] the Egyptian investigative committee announced on 23 June that both recorders would be sent to France's BEA to have salt deposits from the memory chips removed; the recorders would then be returned to Egypt for analysis.[74]

On 27 June, the BEA announced that the FDR had been repaired and sent back to Cairo for data analysis by civil aviation safety authorities.[75]

Early responses

Initially, the disappearance and crash of Flight 804 was assumed to be linked to terrorism and insurgency in the region. Thus, for instance, the Egyptian Civil Aviation Ministry stated on 19 May that Flight 804 was probably attacked.[16][76] Two US officials believed the aircraft was downed by a bomb,[77] and a senior official said that monitoring equipment focused on the area at the time detected evidence of an explosion on board the aircraft; other officials from multiple US agencies said they had seen no evidence of an explosion in satellite imagery and another two intelligence officials stated there is nothing yet to indicate foul play.[78]

Investigation

According to Greek military radar data, Flight 804 veered off course shortly after entering the Egyptian flight information region. At Flight Level 370 (about 37,000 ft (11,300 m) in altitude), the aircraft made a 90-degree left turn, followed by a 360-degree right turn, and then began to descend sharply. Radar contact was lost at an altitude of about 10,000 ft (3,000 m).[79][80] This information was later denied on 23 May by an Egyptian official from the National Air Navigation Services Company, who stated there was no change in altitude and no unusual movement before the aircraft disappeared from radar.[20] On 14 June, Egyptian authorities confirmed the statements made by Greek officials.[22]

On 19 May, Greece's Ministry of National Defence reported that it was investigating the report of a merchant ship captain who claimed to have seen a "fire in the sky" 240 km (150 mi; 130 nmi) south of the island of Karpathos.[81]

Shortly after the disappearance, the French government began to investigate whether there had been a security breach at Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport.[82]

- 00:26Z 3044 ANTI ICE R WINDOW

- 00:26Z 561200 R SLIDING WINDOW SENSOR

- 00:26Z 2600 SMOKE LAVATORY SMOKE

- 00:27Z 2600 AVIONICS SMOKE

- 00:28Z 561100 R FIXED WINDOW SENSOR

- 00:29Z 2200 AUTO FLT FCU 2 FAULT

- 00:29Z 2700 F/CTL SEC 3 FAULT

Seven messages sent via the Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) had been received from the aircraft between 02:26 and 02:29 local time;[33] contact was lost four minutes later at 02:33.[33][83] The data, confirmed by France's Bureau of Investigations and Analysis,[84] indicates that smoke may have been detected in the front of the airliner—in the front lavatory and the avionics bay beneath the cockpit.[83][85] Smoke detectors of the type installed on the aircraft can also be triggered by the condensation of water vapour, producing fog, in the event of a sudden loss of pressure inside the cabin. The aircraft's optical smoke detectors have been deemed more reliable than older models on Airbus aircraft, as they produced fewer false warnings, but were sensitive to dust and some aerosols.[86] The three windows mentioned in the data are cockpit windows, on the co-pilot's side.[87] The flight control unit (FCU) is a cockpit-fitted unit that the pilot uses to enter instructions into the two flight management guidance computers (FMGC); an FCU 2 fault indicates a loss of connection between the FCU and FMGC number 2. The spoiler elevator computer number 3 (SEC 3) is one of the three computers that controls the spoilers and elevator actuators.[88] Two pilots—one interviewed by The Daily Telegraph, the other writing for The Australian—interpreted the data as possible evidence of a bomb.[89][90]

At 02:36, seven minutes after the last ACARS message and the last ADS-B transmission, two transmissions from the aircraft's Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) were received by the international Cospas-Sarsat system. These transmissions indicated that they were initiated in "test" mode, suggesting either an unusual manipulation of the cockpit ELT switch, or an electrical fault in the switch's circuit. The transmissions were received by Cospas-Sarsat's then-experimental MEOSAR system, and subsequent data collection and analyses by the Cospas-Sarsat Secretariat and engineers at France's Centre national d'études spatiales (CNES) were successfully used to calculate the likely point of impact of the flight in the Mediterranean Sea.[91][92][93]

Aviation expert David Learmount of Flight International suggested that an electrical fire could have started in the aircraft's avionics compartment[94] and that the aircrew may have been too distracted to communicate their distress to air traffic control.[95]

On 22 May, the French television station M6 reported that, contrary to official statements, one of the pilots told Cairo air traffic control about smoke in the cabin, and decided to make an emergency descent.[96] Later that day, the report was dismissed as false by the Egyptian Civil Aviation Ministry.[97]

On 24 May, a forensics official from Egypt's investigative team said that the remains of the victims indicated an explosion on board.[98] The head of forensics denied the claim.[99]

At the beginning of June, France 3 and Le Parisien reported that the aircraft had performed three emergency landings in the hours before the crash—at Asmara, Tunis, and Cairo—followed by technical inspections, after ACARS messages "signalled anomalies on board shortly after takeoff from three airports".[46][100] On 2 June, Safwat Musallam, EgyptAir's chairman, denied the report.[46]

With investigations into the crash ongoing, Egyptian officials announced on 29 June that data recovered from the flight data recorder, as well as recovered wreckage from the plane, indicated that smoke had occurred on the aircraft, which matched previous information relayed by the plane's automated systems (ACARS).[2][101] Egyptian Civil Aviation Ministry experts have suggested that wreckage from the front section indicates high temperature combustion.[2][101][102] Also, the data showed that the flight data recorder recorded the smoke and fault alarms at the same moment that the aircraft's ACARS relayed messages about them to the ground station, and that the data recorder stopped recording at an altitude of 37,000 ft (11,300 m) above sea level.[103][104][105] Media reported that data from the cockpit voice recorder indicated one of the pilots had tried to extinguish the fire in the cockpit before the airplane crashed.[106] However, after these reports were released, the Egyptian Civil Aviation Authority urged "media to be cautious while issuing press releases about the accident and to only rely on official reports issued by the committee itself."[107] Later, on 16 July, the committee confirmed that the cockpit voice recording mentioned "the existence of a fire".[56]

On 22 July, investigators privately suggested that the aircraft might have broken up in mid-air.[108]

On 17 September 2016, Reuters relayed a 16 Sep report from the French news outlet Le Figaro that French forensic investigators visiting Cairo noted traces of the explosive TNT on the aircraft debris. According to Le Figaro's source, Egypt proposed a joint report with France announcing the discovery of evidence of an explosive, but France declined, alleging that Egyptian judicial authorities did not allow the French investigators "to carry out an adequate inspection to determine how the traces could have got there".[109]

On 15 December 2016 Egyptian investigators announced that traces of explosives had been found on the victims, although a source close to the French investigation expressed doubts about Egypt's latest findings.[110][111] On 13 January 2017, French newspaper Le Parisien published an article claiming that unspecified "French authorities" believed the aircraft might have been brought down by a cockpit fire caused by an overheating phone battery; it noted parallels between the position where the co-pilot had stowed his iPad and iPhone 6S and data that suggested an accidental fire on the right-hand side of the flight deck, next to the co-pilot.[112]

On 7 May 2017, French officials stated that no traces of explosives had been found on the bodies of the victims.[5]

On 6 July 2018, France's BEA stated that the most likely hypothesis was a fire in the cockpit that spread rapidly.[6]

French manslaughter investigation

In June 2016, Paris prosecutor's office indicated that a preliminary investigation into the accident would begin, since no evidence of any act of terrorism had been found; the office had opened a manslaughter investigation instead.[113][114]

In April 2019, a report commissioned as part of the French investigation and seen by Le Parisien stated the aircraft was not airworthy. On at least four previous flights recurring defects were not reported by the crews and the aircraft was not checked according to procedure. Some twenty alerts (visual and audible) had been made by the ECAM system the day before the flight, including alerts reporting an electrical problem that could lead to a fire. Pilots instead reset circuit breakers and cleared the messages. More alerts had been noted as far back as 1 May 2016, but were ignored by the airline.[115]

The premises of BEA had to be searched under warrant as part of the investigation to obtain these data. The BEA claimed that under international aviation law they were not responsible for supplying information to French judicial investigators. While they at first denied having data-recorder data, they later explained that automatic back-ups had retained the data after the original files had been deleted.[116]

Crews on the flights preceding the crash told the investigators that they had not encountered any problems during their respective flights.[117] EgyptAir's CEO Ahmed Adel also rejected the French report, citing it as "misleading."[118]

Aftermath

EgyptAir retired the Flight 804 flight number and replaced it with Flight 802 for inbound flights from Paris to Cairo,[119] while the outbound flight number was changed from Flight 803 to Flight 801.[120]

Notes

- Last known location

- The aircraft was an Airbus A320-200 model, also known as the A320ceo to distinguish it from the newer A320neo; the infix -32 specifies it was fitted with IAE V2527-A5 engines.

- Two passengers had dual Egyptian–Canadian citizenship,[25] one of them was travelling on their Egyptian passport.[26]

- The passenger had dual British–Australian citizenship.[27]

References

- @Flightradar24 (19 May 2016). "Our last recorded point of contact with #MS804 is 33.6757, 28.7924 at 36,975 feet" (Tweet). Retrieved 20 May 2016 – via Twitter.

- Sanchez, Ray (29 June 2016). "EgyptAir 804: Recorder shows signs of smoke". CNN. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- Amr, Dina (6 August 2016). "French foreign minister calls for quicker investigations on EgyptAir MS804 crash". Daily News Egypt. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- "Breaking News Egypt Air Flight 804". Breaking News. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- "French investigators say no trace of explosives on EgyptAir victims: Le Figaro". Egypt Independent. 8 May 2017.

- "Fire 'likely cause' of EgyptAir crash". 6 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018 – via www.bbc.com.

- "SU-GCC Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir SU-GCC". Air Fleets. 18 May 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- "SU-GCC – Airbus A320-232 [2088]". Flightradar24. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir flight MS804 disappears from radar between Paris and Cairo – live updates". The Guardian. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir Flight MS804 from Paris has disappeared from radar, airline says". CBC News. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir flight MS804 disappears from radar between Paris and Cairo – live updates: Contact lost 280 km from Egyptian coast". The Guardian. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Karimi, Faith; Alkhshali, Hamdi (19 May 2016). "EgyptAir flight disappears from radar". CNN. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir Flight MS804 from Paris to Cairo 'disappears from radar'". BBC. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir flight MS804 disappears from radar between Paris and Cairo – live updates: Contact lost 280 km from Egyptian coast". The Guardian. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir flight MS804 crash: Plane 'fell 22,000 feet, spun sharply, then disappeared'". The Telegraph. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir flight MS804 disappears from radar between Paris and Cairo – live updates". The Guardian. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Noueihed, Lin; Knecht, Eric (19 May 2016). "EgyptAir flight from Paris to Cairo missing with 66 on board". Reuters. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir crash: Greek minister says flight 'turned 360 degrees right'". BBC News. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir: Crashed flight MS804 'did not swerve'". BBC News. 23 May 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- Ahmed-Ullah, Noreen (30 May 2016). "EgyptAir 804: U of T forensic expert explains what we know so far". News@UofT. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Kholaif, Dahlia; Wall, Robert; Pasztor, Andy (14 June 2016). "New EgyptAir 804 Findings Suggest No Sudden Midair Explosion". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- Nielsen, Kevin; Azpiri, Jon (19 May 2016). "EgyptAir flight from Paris to Cairo crashes in Mediterranean; Canadian among 66 on board". Toronto: Global News. The Canadian Press. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "Statement by Minister Dion on crash of EgyptAir flight MS804". Government of Canada. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Quan, Douglas (19 May 2016). "Saskatoon-born businesswoman one of two Canadians aboard downed EgyptAir plane". Edmonton Journal. Postmedia News. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "Egypt air crash: 2nd Canadian aboard plane ID'd as Medhat Tanious". CBC News. 23 May 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir flight MS804: Australian dual national on missing aircraft". Sydney Morning Herald. 20 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir: 5 questions you asked, answered". CNN. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Walsh, Declan (19 May 2016). "EgyptAir Plane Disappears Over Mediterranean, Airline Says". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir Flight MS804 latest updates". BBC News. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

An EgyptAir source has confirmed to the BBC the names of pilot Mohammed Saeed Ali Ali Shoqeir and co-pilot Mohamed Ahmed Mamdouh Ahmed Assem. On Thursday, the airline said the pilot had 6,275 hours of flying experience, including 2,101 hours on the Airbus A320, while the co-pilot had 2,766 hours of flying experience.

- "EgyptAir flight MS804 disappears from radar between Paris and Cairo – live updates". The Guardian. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir flight from Paris to Cairo disappears with 66 on board". Los Angeles Times. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Hradecky, Simon (19 May 2016). "Crash: Egypt A320 over Mediterranean on May 19th 2016, aircraft found crashed, ACARS messages indicate fire on board". The Aviation Herald. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "La Marine Nationale déploie un de ses Falcon 50M au large de Karpathos" [The Navy deploys one of their Falcon 50Ms off Karpathos]. Avions Legendaires (in French). 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir Jet Disappears Over Mediterranean Sea". Sky News. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Thompson, Nick; Griffiths, James; Ap, Tiffany (19 May 2016). "EgyptAir missing plane MS804: Live updates". CNN. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ABC News. "EgyptAir 804 Black Boxes Remain Unrecovered: What We Know About the Hunt for Answers". ABC News. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir didn't swerve before crashing, Egyptian authorities say". CBC News. 23 May 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- "Sentinel-1A Spots Potential Oil Slick from Missing EgyptAir Plane". European Space Agency. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- Sirgany, Sarah; Abdelaziz, Salma; Park, Madison (26 May 2016). "Report: Signals detected from EgyptAir Flight 804 in Mediterranean". CNN. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- El-Ghobashy, Tamer; Kholaif, Dahlia; Wall, Robert (26 May 2016). "Searchers Detect Emergency Signal of EgyptAir Plane". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- "Underwater Locator Beacon (ULB)". skybrary.aero. Eurocontrol. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- "Distress signal from EgyptAir flight 804 confirmed by authorities in Cairo and US". The Guardian. 31 May 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- O'Rourke, Andi (19 May 2016). "Did EgyptAir Flight MS804 Send Out A Distress Signal? There Are Mixed Reports Coming From EgyptAir Officials". Bustle. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Fahim, Kareem; Youssef, Nour (19 May 2016). "Distress Signal Received From Missing Plane". New York Times. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Noueihed, Lin; Lough, Richard; Young, Sarah (2 June 2016). "EgyptAir black box search zone narrows after signal detected". Reuters India. Cairo. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- Noueihed, Lin; Labbé, Chine; Williams, Alison (1 June 2016). "French vessel detects signals likely from EgyptAir jet black box". Reuters. Cairo. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "EgyptAir crash: Black box signals heard by search teams". BBC News. 1 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "Vessel details for: JOHN LETHBRIDGE (Research/Survey Vessel) – IMO 6525131, MMSI 353177000, Call Sign H8PY Registered in Panama". MarineTraffic. 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- Viscusi, Gregory; Levin, Alan; Rothman, Andrea (28 May 2016). "Egypt brings in specialized deep search ship for Egyptair hunt". Chicago Tribune. Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- "French vessel joins EgyptAir black box search". Aljazeera. 28 May 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir flight MS804: Black boxes impossible to recover before 12 days, investigators say". ABC News (Australia). Agence France-Presse. 30 May 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir black box signals will soon cease". Middle East Eye. 13 June 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- Michael, Maggie (15 June 2016). "Egypt Says It Has Found Plane Wreckage". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- تقرير رقم (24) الصادر عن لجنة التحقيق المصرية فى حادثة طائرة مصر للطيران [Investigation Progress Report (24) by the Egyptian Aircraft Accident Investigation Committee]. Ministry of Civil Aviation (Egypt) (in Arabic). 9 July 2016. Archived from the original on 19 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- تقرير رقم (25) الصادر عن لجنة التحقيق المصرية فى حادثة طائرة مصر للطيران [Investigation Progress Report (25) by the Egyptian Aircraft Accident Investigation Committee]. Ministry of Civil Aviation (Egypt) (in Arabic). 16 July 2016. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- "EgyptAir: Submarine searches for missing flight data recorders". BBC News. 22 May 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- "Egyptian submarine to visit plane crash site". CTV News. Associated Press. 22 May 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- "Egypt sends submarine to hunt for crashed EgyptAir jet". Reuters. 22 May 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- "Signals detected from EgyptAir Flight 804". NBC 11 News. Associated Press. 27 May 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- "Disparition du vol d'EgyptAir: La marine française mobilisée" [The disappearance of the EgyptAir flight: The French Navy mobilises]. Mer et Marine (in French). 20 May 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- Pearson, Michael (24 May 2016). "EgyptAir Flight 804: Conflicting reports over final moments". CNN. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- Staff and agencies in Cairo (26 May 2016). "EgyptAir flight 804: deep-sea hunt for 'black boxes' as week passes since crash". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir crash: French naval ship to join search". BBC News. 27 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Clark, Nicola; Walsh, Declan; Youssef, Nour (27 May 2016). "Investigators Race to Find EgyptAir Jet's Black Boxes". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir Black Boxes Badly Damaged, Likely to Prolong Probe". The New York Times. 17 June 2016. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Peter Yeung (16 June 2016). "EgyptAir crash: Black box cockpit voice recorder from flight MS804 'found in Mediterranean Sea'". The Independent. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- "EgyptAir crash: Second flight recorder recovered". BBC News. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- Pearson, Michael; Brascia, Lorenza (17 June 2016). "Egyptair Wreckage Found". CNN. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- Gubash, Charlene; Gittens, Hasani (19 June 2016). "Investigators Begin Examining EgyptAir Flight MS804 Black Boxes". NBC News. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- Ansari, Azadeh; Sirgany, Sarah (21 June 2016). "EgyptAir Flight 804: Memory chips damaged". CNN. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- "Damaged memory chips of EgyptAir Flight 804 being repaired". New Kerala. 21 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- "EgyptAir MS804 flight recorders: efforts to extract data fail | World news". The Guardian. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- "EgyptAir Flight MS804 recorders to go to Paris for repairs". BBC News. 19 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Wall, Robert (2 July 2016). "EgyptAir Flight 804 Cockpit Recorder Successfully Repaired". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- "Egyptair flight MS804: 'Terrorism more likely than technical failure', says Egypt – live". The Guardian. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "U.S. officials believe EgyptAir brought down by bomb". CNN. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "Hunt for EgyptAir Flight MS804 ongoing as mystery surrounds events on plane". CNBC. 20 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "Π. Καμμένος: Στα 10.000 πόδια χάθηκε η εικόνα του airbus – Συνεχίζονται οι έρευνες" [P. Kammenos: At 10,000 feet [was] lost the image of the Airbus – Ongoing investigation] (in Greek). YouTube. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir flight MS804 crash: Plane 'swerved' suddenly before dropping off radar over Mediterranean Sea". The Independent. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Noueihed, Lin; Knecht, Eric (19 May 2016). "EgyptAir flight from Paris to Cairo missing with 66 on board". Reuters Africa. Cairo. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- "EgyptAir flight MS804: What we know". BBC News. 20 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir: 'Smoke detected' inside cabin before crash". BBC News. 20 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- Harding, Luke; Smith, Helena (21 May 2016). "EgyptAir MS804 crash still a mystery after body part and seats found". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir crash: 'Smoke alerts' in cabin before crash". The Local. 21 May 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Pasztor, Andy (27 May 2016). "Smoke Alerts Like That on Flight 804 Have Raised Questions in the Past". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- Sanchez, Raf (21 May 2016). "Smoke in the cabin: what does the data from EgyptAir MS804's sensors mean?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir flight MS804 wreckage found". ITV. 20 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "Smoke in the cabin: what does the data from EgyptAir MS804's sensors mean?". The Telegraph. 21 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir Flight 804: absence of pilot mayday points to bomb blast". The Australian. 21 May 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016. (subscription required)

- The Guardian newspaper, "Distress signal from EgyptAir flight 804 confirmed by authorities in Cairo and US"

- Bloomberg press, "Satellites Captured Doomed EgyptAir Jet’s Distress Signals"

- New York Times, "Black Box from Missing EgyptAir Flight 804 is Said to be Detected"

- "Possibility of fire aboard EgyptAir flight raised as body parts, debris found in Mediterranean". Fox News. 21 May 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- Jamieson, Alastair (21 May 2016). "Smoke Detected on EgyptAir MS804 Before Crash: French Investigators". NBC News. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- Lichfield, John (22 May 2016). "EgyptAir flight MS804 pilot spoke with air traffic control 'for several minutes before crash'". The Independent. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- "بيان عاجل من الشركة الوطنية لخدمات الملاحة الجوية" [Urgent statement from the National Air Navigation Services Company]. Egyptian Ministry of Civil Aviation. 22 May 2016. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- Dearden, Lizzie (24 May 2016). "EgyptAir crash: Human remains retrieved from flight MS804 crash site 'point to an explosion on board'". The Independent. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- "EgyptAir crash: Forensics chief denies explosion claim". BBC News. 24 May 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- Steven Hopkins (2 June 2016). "EgyptAir Flight MS804 Made 'Three Emergency Landings' In 24 Hours Before Crashing into The Mediterranean Sea". The Huffington Post UK. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- تقرير رقم (19) الصادر عن لجنة التحقيق المصرية فى حادثة طائرة مصر للطيران [Investigation Progress Report (19) by the Egyptian Aircraft Accident Investigation Committee]. Ministry of Civil Aviation (Egypt) (in Arabic). 29 June 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- Brascia, Lorenzia; Shoichet, Catherine E. (6 July 2016). "EgyptAir Voice Recorder Indicates Fire on Doomed Plane". Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Pasztor, Andy; Kholaif, Dahlia; Wall, Robert (29 June 2016). "Wreckage, 'Black Box' Data Point to Fire Aboard EgyptAir Flight 804". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- "EgyptAir crash: Flight MS804 black box 'confirms smoke'". BBC News. BBC. 29 June 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- Ali, Randa; Dooley, Erin (29 June 2016). "EgyptAir Flight 804 Data Recorder Indicates Smoke in Bathroom". ABC News. ABC News. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- "EgyptAir black box data reveals pilot tried to put out a fire on board". The Independent. 5 July 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- تقرير رقم (22) الصادر عن لجنة التحقيق المصرية في حادث طائرة مصر للطيران [Report No. (22) Issued by Egyptian Investigative Committee for the Aircraft Accident of EgyptAir]. Egyptian Civil Aviation Ministry (in Arabic). 5 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- Youssef, Nour; Stack, Liam (22 July 2016). "EgyptAir Flight 804 Broke Up in Midair After a Fire, Evidence Suggests". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Rosemain, Mathieu (17 September 2016). "TNT traces on EgyptAir plane debris split investigators – Le Figaro". Reuters UK. Paris. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "EgyptAir crash: Explosives found on victims, say investigators". BBC. 15 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- "Traces of explosives found on EgyptAir crash victims, say authorities". The Guardian. 15 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Overheating phone in cockpit may have caused fire that brought down EgyptAir flight MS804". International Business Times. 13 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "EgyptAir crash: Flight data recorder repaired – investigators". BBC News. BBC. 28 June 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- "Egypt says flight 804 'black box' fixed as France opens manslaughter case". The Guardian. 28 June 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- "L'Airbus A320 d'Egypt Air qui s'est écrasé en 2016 n'était pas en état de voler" [The EgyptAir Airbus A320 that crashed in 2016 was not able to fly]. Le Monde (in French). Agence France-Presse. 2 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Vérier, Vincent (2 April 2019). "Crash d'EgyptAir : le prestigieux Bureau d'enquêtes et d'analyses perquisitionné". leparisien.fr. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Point.fr, Le (2 April 2019). "Crash d'EgyptAir : la transparence du BEA pose question" [EgyptAir crash: BEA transparency raises questions]. Le Point (in French). Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Rivers, Martin. "EgyptAir Set For Restructuring As Questions Linger Over 2016 Crash". Forbes. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "MS802 Flight, EgyptAir, Paris to Cairo". www.flightr.net. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- Sanchez, Raf; Samaan, Magdy (22 May 2016). "EgyptAir crash: Flight data points to 'internal explosion' on plane once daubed with graffiti saying 'We will bring this plane down'". The Telegraph. Cairo: Telegraph Media Group. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to EgyptAir Flight 804. |

- Archived live updates (no longer updated) – The Guardian

- Archived live updates (no longer updated) – BBC News

- EgyptAir MS 804 Paris Cairo (Alt link at Emergency Page) – EgyptAir

- Statements regarding the loss of Egyptair Flight 804 – Airbus, the manufacturer of the aircraft involved

- Accident to the Airbus A320, registered SU-GCC and operated by Egyptair and Accident to the Airbus A320, registered SU-GCC and operated by Egyptair, on 05/19/2016 in cruise off the Egyptian coast – the French Bureau of Investigation and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety

- (in English and Arabic) Press releases – Egyptian Ministry of Civil Aviation