Canadian nationality law

Canadian nationality (French: Nationalité canadienne) is regulated by the Citizenship Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-29) since 1977.[1] The Act determines who is, or is eligible to be, a citizen of Canada. Having replaced the previous Canadian Citizenship Act (S.C., 1946, c. 15; R.S.C. 1970, c. C-19) in 1977,[1][2] the Act has gone through four significant amendments, in 2007, 2009, 2015, and 2017.

| Citizenship Act | |

|---|---|

| |

| Parliament of Canada | |

| |

| Citation | R.S.C., 1985, c. C-29 |

| Enacted by | 30th Canadian Parliament |

| Commenced | 1977 |

| Repeals | |

| Canadian Citizenship Act (R.S.C. 1970, c. C-19) | |

| Status: Current legislation | |

| Part of a series on |

| Canadian citizenship and immigration |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

Canadian citizenship is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in Canada; or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth abroad to at least one parent with Canadian citizenship or by adoption by at least one Canadian citizen. It can also be granted to a permanent resident who has lived in Canada for a given period of time through naturalization. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC; formerly known as Citizenship and Immigration Canada, CIC) is the department of the federal government responsible for citizenship-related matters, including confirmation, grant, renunciation, and revocation of citizenship.

On 19 June 2017, the Citizenship Act was amended for a fourth time by the 42nd Canadian Parliament. As result, a set of changes have taken effect throughout 2017 and 2018, mostly in regard to naturalization requirements and citizenship deprivation procedures.[3]

British nationality law in Canadian history

| British citizenship and nationality law |

|---|

|

| Introduction |

| Nationality classes |

|

| See also |

| Relevant legislation |

Canadian independence from Britain was obtained incrementally between 1867 (confederation and Dominion status within the Empire) and 1982 (patriation of the Canadian constitution).

Following the Confederation of Canada in 1867, the new Dominion's "nationality law" closely mirrored that of the United Kingdom, whereby all Canadians were classified as British subjects. Though having been passed by the British Parliament in London, section 91(25) of the Dominion's British North America Act, 1867 (now referred to as the Constitution Act, 1867) gave the Parliament of Canada explicit authority over "Naturalization and Aliens."

A few decades later, the Immigration Act, 1910 created the status of "Canadian citizen,"[4][5] distinguishing those British subjects who were born, naturalized, or domiciled in Canada from those who were not. However, it would only be applied for the purpose of determining whether someone was free of immigration controls.[6]

The Naturalization Act, 1914, increased the period of residence required to qualify for naturalization in Canada as a British subject from three years to five years.[7] A separate, additional status of "Canadian national" was subsequently created under the Canadian Nationals Act, 1921, with the immediate purpose of securing Canadian participation in the newly created Court of International Justice, as well as "to recognize who is a Canadian and who is not."[7]:36 More broadly, its purpose would be:[7]:36

…to define a particular class of British subjects who, in addition to having all the rights and all the obligations of British subjects, have particular rights because of the fact that they are Canadians.

In 1931, the Statute of Westminster provided that the United Kingdom would have no legislative authority over Dominions without the request and consent of that Dominion's government to have a British law become part of the law of the Dominion. The Statute also left the British North America Acts within the purview of the British parliament, as the federal government and the provinces could not agree on an amending formula for the Canadian constitution. (Similarly, the neighbouring Dominion of Newfoundland did not become independent because it never ratified the Statute.)

Evidently, Canada's naturalization laws within the 1930s consisted of a hodgepodge of confusing acts, still retaining the term "British subject" as the only nationality and citizenship of "Canadian nationals."[8] This would eventually conflict with the nationalism that arose following the First and Second World Wars, accompanied by the desire to have the Dominion of Canada's sovereign status reflected in distinct national symbols (such as flags, anthem, seal, etc.).[9] Such factors would ultimately prompt the enactment of the Canadian Citizenship Act, 1946, taking effect on 1 January 1947, after which Canadian citizenship would be conferred on British subjects who were born, naturalized, or domiciled in Canada. Subsequently, on 1 April 1949, the Act was extended to the former British Dominion of Newfoundland upon joining the Canadian confederation as the province of Newfoundland.

However, the Act did not remove preference for British immigrants or the special status of British subjects: not only would British citizens still be fast-tracked through the naturalization process, they would possess the ability to vote prior to becoming Canadian citizens. Additionally, while the Act had created a separate legal concept of 'Canadian citizenship,' Canadians still remained part of a wider status of 'British subject.' Specifically, article 26 of the Citizenship Act 1946 declared that “[a] Canadian Citizen is a British Subject.” The ability for British subjects to vote in Canada on the federal level would not be removed until 1975, after which it would still not be fully phased out in all provinces until 2006.[10][11][12]

The concept of the 'British Subject' would remain until the enactment of Citizenship Act, 1976, in which the label of would be replaced by the term 'Commonwealth citizen.' Bringing about substantial revisions to its predecessor, the new 1976 Act officially came into force on 15 February 1977, after which multiple citizenship would become legal. Those who had lost Canadian citizenship before the effectuation of the 1976 Citizenship Act did not automatically have it restored until 17 April 2009, when Bill C-37 came into law.[13]

In 1982, the British and Canadian parliaments produced the mutual Canada Act 1982 (UK) and Constitution Act 1982 (Canada), which included a constitutional amendment process. As result, the UK ceased to have any legislative authority whatsoever over Canada.

In 2009, Bill C-37 would limit the issuance of citizenship to children born outside of Canada to Canadian ancestors (jus sanguinis) to one generation abroad.[14] In 2015, Bill C-24 further granted Canadian citizenship to British subjects with ties to Canada but who did not qualify for Canadian citizenship in 1947 (either because they had lost British subject status prior to 1947, or did not qualify for Canadian citizenship in 1947 and had not yet applied for naturalization).[14]

Acquiring Canadian citizenship

There are four ways an individual can acquire Canadian citizenship: by birth on Canadian soil; by descent (being born to a Canadian parent); by grant (naturalization); and by adoption. Among these, only citizenship by birth is granted automatically with limited exceptions, while citizenship by descent or adoption is acquired automatically if specified conditions have been met. Citizenship by grant, on the other hand, must be approved by the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship.

By birth in Canada

In general, persons born in Canada on or after 1 January 1947 (or 1 April 1949 if born in Newfoundland and Labrador) automatically acquire Canadian citizenship at birth unless they fall into one of the exceptions listed below. Those born in Canada before 1947 automatically acquired Canadian citizenship either on 1 January 1947 (or 1 April 1949 for Newfoundland and Labrador residents) if they were British subjects on that day, or on 11 June 2015 if they had involuntarily lost their British subject status before that day. Despite being indigenous to Canada, many First Nations peoples (legally known as Status Indians) and Inuit born before 1947 did not acquire Canadian citizenship until 1956, when only those who met certain conditions were retroactively granted citizenship.

In 2012, Citizenship and Immigration Minister Jason Kenney proposed to modify the jus soli, or birthright citizenship, recognized in Canadian law as a means of discouraging birth tourism. The move had drawn criticism from experts who said that the proposal was based on overhyped popular beliefs and nonexistent data.[15] As of 2016, however, there is no plan to end birthright citizenship, according to an interview with Minister John McCallum.[16]

Current legislation

Under paragraph 3(1)(a) of the 1977 Act, any person who was born in Canada on or after 15 February 1977 acquires Canadian citizenship at birth. The Interpretation Act states that the term "Canada" not only includes Canadian soil, but also "the internal waters"—defined as including "the airspace above"—and "the territorial sea" of Canada.[17] Hence, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) considers all children who were born over Canadian airspace as Canadian citizens.[18] In one 2008 case, a girl born to a Ugandan mother aboard a Northwest Airlines flight from Amsterdam to Boston was deemed a Canadian citizen because she was born over Canadian airspace.[19]

In addition, the interpretation section of the Citizenship Act states that any person who was born on an aircraft registered in Canada, or a vessel registered in Canada, is considered to be born in Canada. There are only three exceptions to this rule, listed below.

Exceptions

Subsection 3(2) of the Citizenship Act states that Canadian citizenship by birth in Canada is not granted to a child born in Canada if neither parent is a Canadian citizen or permanent resident, and either parent was recognized by Global Affairs Canada as employed by the following at the time of the child's birth:[20]

- a foreign government in Canada;

- an employee of the foreign government in Canada; or,

- a foreign organization which enjoys diplomatic immunity in Canada, including the United Nations.

In the decision of Canada v Vavilov,[21] the Federal Court of Appeal clarified that to qualify for one of such exceptions, the parent's status as an employee of a foreign government must be recognized first by Global Affairs Canada. The exceptions do not apply if the said parent is employed by a foreign state but never had that status recognized by the federal government.[22]

In a high-profile case in 2015, Deepan Budlakoti, a stateless man born in Ottawa, Ontario, was declared not to be a Canadian citizen because his parents were employed as domestic staffs by the High Commissioner of India in Canada and their contracts, which came with recognized diplomatic statuses, legally ended two months after his birth, despite the fact that they started to work for a non-diplomat well before their contracts ended and before Budlakoti was born.[23][24]

Previous legislation

Under section 4 and 5 of the 1947 Act, all persons who were born on Canadian soil or a ship registered in Canada on or after 1 January 1947 acquired Canadian citizenship at birth, while those who were born before that date on Canadian soil or Canadian ships acquired Canadian citizenship on 1 January 1947 if they had not yet lost their British subject status on that day. This Act was amended to include Newfoundland in 1949.[25]

Before 1950, a loophole existed in a way that section 5 of the 1947 Act did not mention any exceptions to this rule for persons born after 1947, making persons born to diplomats between this period also Canadian citizens by birth. This loophole was closed in 1950 when the first amendments to the 1947 Act went into effect, which specified that the jus soli rule does not apply to children with a "responsible parent" (father if born in wedlock; mother if born out of wedlock or has custody of the child) who was not a permanent resident and who also was:[26]

- a diplomatic or consular officer;

- an employee of a foreign government; or,

- a person employed by a diplomatic or consular officer.

Hence, between 1950 and 1977, it was possible for children born to foreign diplomat fathers and Canadian mothers not to be Canadian citizens.

First Nations and Inuit

Although the 1947 Act declared that British subjects who were born in Canada prior to 1947 acquired Canadian citizenship on 1 January 1947, First Nations and Inuit were left out of the 1947 Act because those who were born before 1 January 1947 were not British subjects.[26] It was not until 1956 when the legal loophole was closed by amending the 1947 Act to include Status Indians under the Indian Act and Inuit who were born prior to 1947. To be eligible for Canadian citizenship, they must have had Canadian domicile on 1 January 1947 and must have had resided in Canada for over ten years on 1 January 1956. Those qualified were deemed to be Canadian citizens from 1 January 1947.[27] In comparison, those born on or after 1 January 1947 acquired Canadian citizenship at birth on the same basis as any other person born in Canada.

Persons born in Canada before 1947

The 2015 amendment (Bill C-24) of the 1977 Act, which went into effect on 11 June 2015, granted Canadian citizenship for the first time to people who were born in Canada before 1 January 1947 (or 1 April 1949 if born in Newfoundland and Labrador), ceased to be British subjects before that day, and never became Canadian citizens after 1947 (or 1949). Under the 1947 Act, these people were never considered to be Canadian citizens because they had lost their British subject status before the creation of Canadian citizenship. Persons who had voluntarily renounced British subject status or had their British subject status revoked are not included in the grant.[28]

By descent

Whether a person is a Canadian citizen by descent depends on the legislation at the time of birth. Generally speaking, any person who was born to a parent born or naturalized in Canada who has not actively renounced their Canadian citizenship is a Canadian citizen by descent (known as first generations born abroad), regardless of the time of birth. (Such renunciation of Canadian citizenship is considered valid only if it is addressed to Canadian immigration authorities.) These persons either automatically acquired Canadian citizenship at birth, or on 17 April 2009 or 11 June 2015. A small number of persons who voluntarily obtained Canadian citizenship through special grant programs before 2004 were either retroactively granted citizenship since birth or gained citizenship on the day their application was approved.

Cases for children of first generations born abroad (known as second and subsequent generations born abroad) are more complicated. For such persons, only those who were born on or before 16 April 2009 may be Canadian citizens.

Current legislation

Under Bill C-37 which went into force on 17 April 2009, every person born outside of Canada as the first generation born abroad (i.e., born to a Canadian parent who derives their citizenship from birth or naturalization in Canada) on or after 17 April 2009 is automatically a Canadian citizen by descent at birth.

The Bill also automatically granted Canadian citizenship, for the first time, to children of former Canadian citizens whose citizenship was restored on that day (which was every person who involuntarily lost Canadian citizenship under the 1947 Act). On 11 June 2015, Bill C-24 further extended the automatic grant to children of British subjects who were born or naturalized in Canada but never acquired Canadian citizenship. The acquisition of citizenship under both bills is not retroactive to birth.[18]

Children born abroad on or after 17 April 2009 to Canadian citizens by descent, and children born abroad to Canadian citizens by descent who acquired their citizenship en masse on 17 April 2009 or 11 June 2015 are subject to the first generation rule and hence are not Canadian citizens. They must go through the naturalization or adoption process to become Canadian citizens.[18]

The "Crown servant" exceptions to the first-generation rule are:[18]

- at the time of the child's birth, a parent of the child is a Canadian citizen employed by a Canadian government (federal, provincial, or territorial), including the Canadian Armed Forces; or,

- at the time of the child's parent's birth, that parent's parent was a Canadian citizen employed by a Canadian government (federal, provincial, or territorial), including the Canadian Armed Forces.

2009 amendments

An Act to amend the Citizenship Act (S.C. 2008, c. 14; previously Bill C-37)[14] came into effect on 17 April 2009[lower-roman 1][29] and changed the rules for Canadian citizenship. Individuals born outside of Canada are Canadian citizens by descent only if one of their parents is a citizen of Canada either by having been born in Canada or by naturalization. The new law limits citizenship by descent to one generation born outside Canada.

In a scenario, the new rules would apply like this: A child is born in Brazil in 2005 (before the new rules came into effect) to a Canadian citizen father, who himself is a born abroad citizen by descent, and a Brazilian mother who is only a Permanent Resident of Canada. The child automatically becomes a Canadian citizen at birth. Another child born after 17 April 2009 in the same scenario would not be considered a Canadian citizen. The child is considered born past "first generation limitation" and the parents would have to sponsor the child to become a Permanent Resident. Once permanent residency is granted, a parent can apply for Canadian citizenship on behalf of the child under subsection 5(2) without the residency requirement.[14]

Children born on or after 17 April 2009 as second and subsequent generations born abroad have no claim to Canadian citizenship other than naturalization or adoption. Before Bill C-6's passage on 19 June 2017, such children might be stateless if without claim to any other citizenship. In one case, a toddler who was born in Beijing out of wedlock to a Chinese mother and a Canadian father who acquired his citizenship by descent was left de facto stateless for 14 months until she was registered for Irish citizenship because of her Irish-born grandfather.[30] Since 19 June 2017, parents of otherwise stateless children can apply for naturalization on the sole ground of being stateless without fulfilling any of the requirements for citizenship.

Previous provisions

Between 15 February 1977 and 16 April 2009, a child born abroad to a Canadian citizen would acquire Canadian citizenship automatically at birth, regardless of whether the parent was a Canadian citizen by descent.[31] During this period, the parent must have retained their Canadian citizenship at the time of their birth for them to be eligible for Canadian citizenship. Hence, those with a parent who involuntarily lost their citizenship under the 1947 Act (e.g., by naturalizing in another country) were not considered as Canadian citizens.

However, a Canadian citizen who was born outside Canada after the first generation between 15 February 1977 and 16 April 1981 was required to apply for the retention of Canadian citizenship before their 28th birthday. Otherwise, their Canadian citizenship would be automatically lost.[31]

Between 1947 and 1977, a person born to a Canadian citizen parent would only acquire Canadian citizenship if his or her birth was registered at a Canadian embassy, consulate or high commission. Canadian citizenship between this period could only be passed down by Canadian fathers when born in wedlock, or Canadian mothers when born out of wedlock.[25] Although the 1947 Act had mandated that a child must be registered within two years from the date of the child's birth, the 1977 Act abolished the mandatory period so that eligible persons and their children born before 1977 could be registered at any age after 15 February 1977 up until 14 August 2004.[32] This provision, known as delayed registration, was retroactive to birth, so children born to these citizens would automatically acquire Canadian citizenship by descent if born between the period of 15 February 1977 to 16 April 2009 and would have to apply for retention if falling under the retention rules (i.e., born between 1977 and 1981).[31]

Although married women were unable to pass down citizenship to their children under the 1947 Act, a provision in the 1977 Act (paragraph 5(2)(b)), before it was repealed on 17 April 2009, also allowed children born to Canadian mothers in wedlock before 1977 to apply for Canadian citizenship through a special grant before 14 August 2004.[33] Unlike that of the delayed registration provision, the grant of citizenship under this provision was not retroactive to birth, and hence children born to such parents would not be Canadian citizens by descent if they were born before their parents' citizenship was granted, because the parents were not yet Canadian citizens at the time of their birth. This special grant was also available for non-Canadian children born to Canadian fathers out of wedlock between the period of 17 May and 14 August 2004 after a court ruling. Those who were born after the parent's citizenship was granted also had to apply for retention if falling under the retention rules.[31]

Those who failed to register or apply for a grant before 14 August 2004 would see their citizenship granted on 17 April 2009 if they were the first generation born abroad. Unlike those registered for or granted citizenship before the 2004 deadline, however, their children will not be able to acquire Canadian citizenship by descent, regardless of the time of birth.

Through naturalization

A person may apply for Canadian citizenship by naturalization under section 5 of the Act if the outlined conditions are met. In certain cases, some or all of the requirements may be waived by the Minister.

General provision

Under subsection 5(1), a person of any age may apply for Canadian citizenship if he or she:[34]

- is a permanent resident or a Status Indian[35] (not required for foreign military members); and,

- has been physically in Canada for no less than 1,095 days (i.e., 3 years) during the five years preceding application for citizenship as a permanent resident or a Status Indian (including each day in Canada as a temporary resident or a protected person prior to becoming a permanent resident, which counts as a half-day as a permanent resident for a maximum period of 365 days as a permanent resident); or,

- has completed at least 1,095 days (i.e., 3 years) of service out of six years (2,190 days) in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), including times served as a Regular or Reserved Force member of CAF, or a foreign military member attached or seconded to CAF;[36] and,

- files income tax, if required under the Income Tax Act, during the required period of residence (not required for foreign military members); and,

- is not serving a conditional sentence (or being paroled) at the time of application (period of the entire sentence also does not count toward the physical presentation period);[3] and,

- is not a subject to any criminal prohibitions; and,

- is not a war criminal.[37]

In addition, any applicant between the age of 18 and 54 must:[34]

- pass the Canadian Citizenship Test; and,

- demonstrate sufficient knowledge in English or French, either by passing a language test (administered by the federal or provincial government, or a third party), or providing transcripts that indicate the completion of secondary or post-secondary education in English or French.

Subsection 5(1) does not apply to minors with a Canadian citizen parent or guardian, who must follow subsection 5(2) which has fewer requirements.[38]

Prior to 2015's Bill C-24, the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act, the requirement for time spent in Canada was 1095 days over four years including at least two as a permanent resident (time spent in Canada as a temporary resident could count as one year of residence at most). The language and knowledge requirement applied only to persons aged 18 to 54.[39] Between 17 June 2015 and 11 October 2017, the physical residence period was prolonged to four out of six years, and applicants must spend more than 183 days in Canada each year for at least four years before the day they submit their application. Their time spent in Canada as a temporary resident or a protected person also did not count toward the residence period.

Applications submitted before 11 October 2017 were subject to the longer physical residence requirement. However, knowledge and language requirements no longer apply to persons who were under 18 or over 54 at the time they signed their application, even when their applications were submitted before that date.[40]

The age requirement and the requirement to declare the applicant's intention to reside in Canada or continue the service with the CAF was repealed when Bill C-6 became law on 19 June 2017. Before this date, only those over 18 can apply for naturalization under subsection 5(1).[3] Furthermore, the residence period was changed to three out of five years on 11 October 2017, and applicants are no longer required to reside in Canada for 183 days per year. Once again, time spent as a temporary resident or a protected person is allowed to count toward the period of permanent residence, and the language and knowledge tests no longer apply to persons under 18 or over 54.

All applicants are required to maintain the requirements for citizenship from the day they submit the applications to the day they take the oath.[3]

Special provision for children with a Canadian parent or guardian

Since 19 June 2017, a minor under 18 can apply for citizenship individually under subsection 5(1) if they meet all requirements. In other circumstances, however, the minor child's parent or guardian can apply for Canadian citizenship on their behalf under subsection 5(2). Citizenship will be granted under subsection 5(2) if:[34][41]

- the child is a permanent resident; and,

- a parent of the child is a Canadian citizen or is in the process of applying for Canadian citizenship.

The parent who applies on the child's behalf does not have to be the one with Canadian citizenship. For example, a permanent resident child's non-citizen father can apply for citizenship on their behalf if the mother of the child is a Canadian citizen.[34]

The period of residence requirement does not apply to those applying under subsection 5(2).[3] Minors under 14 years old also do not need to take the oath of citizenship or attend a citizenship ceremony.

Applicants who submitted their applications before 11 October 2017 are no longer required to meet language and knowledge requirements as they no longer apply to any person under 18 years of age.[42]

Stateless children of Canadian citizens by descent

When Bill C-37 became law in 2009, a new provision, subsection 5(5), was also added to provide a path to citizenship for stateless children born to Canadian parents who acquired citizenship by descent. To qualify, the applicants must:[43]

- be born outside Canada on or after 1 April 2009;

- have at least one parent who is a Canadian citizen by descent;

- meet the residency requirement (1,095 days in four years);

- have been stateless since birth (i.e., cannot have a claim to citizenship of another country, and cannot renounce or lose the citizenship of another country); and,

- be less than 23 years of age at the time of application.

Unlike subsections 5(1) and 5(2), subsection 5(5) does not require the applicant to hold permanent resident status to apply (as long as the residence requirement has been met). Additionally, they do not need to attend a ceremony or take the Oath of Citizenship. Other conditions, such as the income tax filing, also do not apply to them.

After 19 June 2017, it is possible for such children to apply for a discretionary grant under subsection 5(4) on the sole ground of being stateless and bypass all requirements, although subsection 5(5) is left intact as a part of the Act.[3]

Compassionate and discretionary cases

Under subsection 5(3), the Minister may waive the following requirements on compassionate or humanitarian grounds:

- the language requirement; and,

- the requirement of taking the Canadian Citizenship Test.

The Minister may further waive the oath requirement for persons with disabilities.

Moreover, under subsection 5(4), the Minister may grant citizenship to individuals who:[3]

- are subject to "special and unusual hardship";

- have rendered services "of an exceptional value to Canada"; or,

- are stateless.

Such persons do not need to fulfill any of the requirements.

Since 1977, naturalization under subsection 5(4) has been used for over 500 times, and in many cases they were used to naturalize professional athletes so they can represent Canada at world events. Several notable athletes naturalized under this clause include Eugene Wang, Kaitlin Weaver and Piper Gilles.[44]

Citizenship ceremonies

All applicants for naturalization aged 14 or over (except for those naturalizing under subsection 5(5) or those with the requirement waived by the minister) must attend a citizenship ceremony as the final stage of their application. After taking the Oath of Citizenship, they will be given a paper citizenship certificate as the legal proof of Canadian citizenship.[45] Before February 2012, applicants would receive a wallet-sized citizenship card and a paper commemorative certificate, but only the citizenship card served as the conclusive proof of Canadian citizenship.[46]

By adoption

Prior to 2007, there was no provision in the Act for adopted persons to become Canadian citizens without going through the process of immigration and naturalization. In May 2006 the federal government introduced draft legislation, Bill C-14: An Act to Amend the Citizenship Act (Adoption), which was designed to allow adopted children the right to apply for citizenship immediately after the adoption without having to become a permanent resident. This bill received Royal Assent on 22 June 2007.[47]

After the passage of the bill, a person who is adopted by a Canadian citizen is entitled to become a Canadian citizen under section 5.1 of the Citizenship Act if

- the adoption takes place on or after 1 January 1947 (1 April 1949 for Newfoundland residents); or,

- the adoption took place before 1 January 1947 (or 1 April 1949 for Newfoundland residents) and the adoptive parent became a Canadian citizen on that day; and,

- the adoption follows the applicable laws of both countries; and,

- the adoption is not for the sole purpose of obtaining Canadian citizenship; and,

- the adoptive parent(s) with Canadian citizenship did not acquire their citizenship by descent or adoption (unless falling into one of the exceptions listed below).

In addition, for adoptees over 18 years old, evidence must be submitted to show that the adoptive parents and the adoptee have a "genuine relationship between parent and child" before the adoptee turned 18.

For Quebec adopters, the adoption must also be approved by the Government of Quebec.

Unlike the execution of citizenship by descent provisions which automatically grants citizenship to first-generation born abroad, the exercise of adoption provisions is voluntary, and adoptees may become Canadian citizens either by immediately applying for Canadian citizenship under section 5.1 or through naturalization under section 5 after the adoptees become permanent residents.[48]

However, those adopted by one or both parents who derived their citizenship by descent or under the adoption provisions are not eligible for citizenship under section 5.1 and must apply for naturalization under section 5, unless the parent concerned, at the time of adoption,

- is serving in the Canadian forces or employed by the federal or provincial government; or,

- was born to or adopted by a parent who was serving in the Canadian forces or employed by the federal or provincial government at the time of birth.

Furthermore, those who acquired citizenship under section 5.1 cannot pass down citizenship to their future offspring born outside Canada through jus sanguinis, while an adoptee who acquired citizenship through naturalization may pass down citizenship to future children born abroad.

Although not included in section 5.1, persons who were adopted before 1 January 1947 were also granted Canadian citizenship on 11 June 2015 if their adoptive parents can pass down citizenship by descent and they had never received Canadian citizenship.[14]

In a 2013 case, the Federal Court ruled that a person applying under section 5.1 has an entitlement to Canadian citizenship if all criteria have been met, even when they are otherwise ineligible for citizenship under naturalization rules (e.g., criminal offences or outstanding deportation orders).

Retention of Canadian citizenship

Currently, there is no longer a requirement to file for retention of Canadian citizenship before a person's 28th birthday after the repeal of section 8 of the Act on 17 April 2009.[14]

Under the 1977 Act

Prior to Bill C-37 entered into force, all Canadians who acquired their Canadian citizenship by descent through a Canadian parent who also acquired Canadian citizenship by descent (known as the second and subsequent generations born abroad) would automatically lose their Canadian citizenship on their 28th birthday under section 8 of the 1977 Act, unless they applied for retention of citizenship.

Retention of citizenship would only be approved for applicants who had satisfied one of the following conditions:[31]

- they had resided in Canada for over one year immediately before the application prior to attaining 28 years of age; or,

- they had provided proof of "substantial connections" with Canada between the age of 14 and 28 (including English and French language test results, proof of attendance at a Canadian school, or proof of employment of the federal or provincial government).

Applications would be considered by a citizenship judge and, if rejected, could be filed again after the applicant had met the requirements. Successful applicants would be issued a citizenship card and a certificate of retention, and both serve as the legal proof of citizenship.[31]

This provision was formally repealed on 17 April 2009 when Bill C-37 came into effect, and those who attained 28 years of age on or after the date no longer has a requirement to retain citizenship. Thus, only those who were born between the period of 15 February 1977 (the day that the 1977 Act went into effect) and 16 April 1981 were required to retain citizenship and, if had not taken steps to do so, would lose their Canadian citizenship between 15 February 2005 and 16 April 2009. However, a child born to such parent would still be a Canadian citizen and no longer had to apply for retention, if he or she was born after 16 April 1981 but before 17 April 2009 and the parent had not formally lost Canadian citizenship at the time of the child's birth. The parent, nevertheless, would face the loss of citizenship if he or she had not successfully filed for retention.

The retention clause of the Act had negatively affected a number of people, many of whom were residing in Canada at the time when their citizenship was stripped. On 4 December 2016, the Vancouver Sun reported that some individuals who were subject to the automatic loss of citizenship had only discovered that they were no longer Canadian citizens while dealing with the federal government.[49] These people would become de jure stateless if also holding no other nationalities or citizenship, and would also have no legal immigration status in Canada after the loss of citizenship. Accordingly, they must take steps to restore their Canadian citizenship under section 11 of the Act.[31] It is worth noting that neither Bill C-37 nor Bill C-24 restored these persons' citizenship, and those affected must take voluntary action or may face legal consequences as illegal immigrants with respect to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act.

Under the 1947 Act

Under section 6 the original 1947 Act in force until 1970, Canadian citizens by descent were required to renounce all foreign citizenship and make a declaration of retention after they attained 21 years of age. Failing to do so before their 22nd birthday would cause the loss of Canadian citizenship on that day.[50]

This requirement was relaxed in 1970. Subsection 5(2) of the 1947 Act, as amended in 1970, specified that Canadian citizens by descent would not lose their Canadian citizenship until their 24th birthday, as opposed to their 22nd birthday under the original clause. Retention of citizenship would be granted to any person who had Canadian domicile on their 21st birthday or those who had submitted a declaration of retention of Canadian citizenship before their 24th birthday. The requirement for them to renounce their foreign citizenship under the original 1947 Act was also repealed.[27]

Unlike that of the 1977 Act which required the affected persons to make an application with the possibility of being refused, the 1947 Act's retention clauses merely required those affected to make a declaration. The clauses also did not make a distinction between the first-generation born abroad to Canada-born or naturalized parents, and second and subsequent generations born abroad. However, under Bill C-37, only those who were the first generation born abroad were able to have their Canadian citizenship restored, while second and subsequent generations born abroad remain foreign if they had failed to retain their Canadian citizenship under the 1947 Act.[14]

The complete replacement of the 1947 Act in 1977 meant that only those who were born on or before 14 February 1953 were subject to the 1947 Act's retention rules. Those born between 15 February 1953 and 14 February 1977 were able to retain their Canadian citizenship without taking any actions.

Loss of Canadian citizenship

Involuntary loss of citizenship

Since Bill C-37 came into force in 2009, there is no provision for involuntary loss of Canadian citizenship, except when in certain circumstances the Minister may initiate court proceedings to revoke a person's citizenship.

Between 1947 and 1977, a number of Canadian citizens had involuntarily lost their citizenship under the 1947 Act, mostly by acquiring the nationality or citizenship of another country.[28] These persons' citizenships were restored en masse on 17 April 2009.

Under the 1977 Act, there were no automatic losses of Canadian citizenship until the period between 2005 and 2009 when some Canadians lost their citizenship due to their failure to file for retention of citizenship.

While there now are no grounds for involuntary loss of citizenship, voluntary loss of citizenship, or renunciation, is permitted.

Lost Canadians and involuntary loss of citizenship under the 1947 Act

The term "Lost Canadians" are used to refer to persons who believed themselves to be Canadian citizens but have lost or never acquired Canadian citizenship due to the legal hurdles in the 1947 Act.

Under the 1947 Act, a person must be a British subject on 1 January 1947 for them to acquire Canadian citizenship. Hence certain persons who were born, naturalized or domiciled in Canada before the enactment of the 1947 Act were ineligible for Canadian citizenship, which included the following groups:[28]

- Any person born, naturalized or domiciled in Canada who had lost their British subject status on or before 31 December 1946 (mostly by naturalizing in a country outside the British Empire);

- Any person born, naturalized or domiciled in Newfoundland who had lost their British subject status on or before 31 March 1949, unless they already acquired Canadian citizenship;

- Any woman who had married a non-British subject man between 22 May 1868 and 14 January 1932 (loss was automatic even when the woman did not acquire her husband's citizenship);

- Any women who had married a non-British subject between 15 January 1932 and 31 December 1946 when she acquired her husband's nationality; and,

- First Nations and Inuit.

After the enactment of the 1947 Act, Canadian citizenship could be automatically lost between 1 January 1947 and 14 February 1977, by the following acts:[28][27]

- voluntarily (i.e., other than marriage) acquiring citizenship of any other country, including a Commonwealth country (loss of citizenship would happen even when the acquisition of another citizenship took place on Canadian soil);

- absenting from Canada for over six years (unless qualified for an exemption) for naturalized Canadians (before 1953) or ten years (before 1967);

- loss of citizenship of the responsible parent (father when born in wedlock; mother when born out of wedlock or when having custody) when the person was a minor (only when he or she is a citizen of another country or has received foreign citizenship along with the parent); or,

- if not residing in Canada, failing to apply for retention of Canadian citizenship before the age of 24 (for persons born outside Canada before 15 February 1953) or 22 (for those born in 1948 or earlier).

The loss of British subject status or Canadian citizenship could occur even when the person was physically in Canada.

Certain Canadian residents born before 1977, including but not limiting to war brides and persons who were born outside Canada to Canadian citizens (primarily those who were born to Canadian servicemen or in U.S. hospitals along the Canada–United States border who automatically acquired U.S. citizenship at birth), also do not possess Canadian citizenship, because it was not possible to automatically acquire Canadian citizenship without voluntarily applying for naturalization (for war brides) or registering at a Canadian mission (for children of Canadians). Some of those people have been living in Canada for their entire lives with little knowledge of their lack of Canadian citizenship. To solve this problem, the federal government had undertaken several legislative processes to reduce and eliminate these cases.

The problem first arose in February 2007, when the House of Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration held hearings on so-called Lost Canadians,[51] who found out on applying for passports that, for various reasons, they may not be Canadian citizens as they thought. Don Chapman, a witness before the committee, estimated that 700,000 Canadians had either lost their citizenship or were at risk of having it stripped.[52] However, Citizenship and Immigration Minister Diane Finley said her office had just 881 calls on the subject. On 19 February 2007, she granted citizenship to 33 such individuals. Some of the people affected reside in towns near the border, and hence were born in American hospitals.[53] Others, particularly Mennonites, were born to Canadian parents outside Canada.[54] An investigation by the CBC, based on Canadian census data, concluded that the problem could affect an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 individuals residing in Canada at the time.[55]

On 29 May 2007, Canadian Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Diane Finley announced her proposal to amend the 1977 Act for the first time. Under the proposal, which eventually became Bill C-37, anyone naturalized in Canada since 1947 would have citizenship even if they lost it under the 1947 Act. Also, anyone born since 1947 outside the country to a Canadian mother or father, in or out of wedlock, would have citizenship if they are the first generation born abroad.[56] Appearing before the Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration, Finley asserted that as of 24 May 2007, there were only 285 cases of individuals in Canada whose citizenship status needs to be resolved.[57] As persons born prior to 1947 were not covered by Bill C-37, they would have to apply for special naturalization before Bill C-24's passage in 2015.[58]

Under Bill C-37 and Bill C-24 which went into effect on 17 April 2009 and 11 June 2015, respectively, Canadian citizenship was restored or granted for those who have involuntarily lost their Canadian citizenship under the 1947 Act or British subject status before 1947, as well as their children.

The aftermath of the 1947 Act continues to affect people today. In July 2017, Larissa Waters, an Australian Senator born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, was disqualified on the ground that she has dual Canadian and Australian citizenship. Section 44 of the Australian Constitution was frequently interpreted by Australian courts as a ban on the ability to run for political office by persons with multiple citizenship. Waters, who was born to Australian parents a week before the 1977 Act went into effect, claimed that she was unaware of the changes in Canadian legislation and was also misinformed by her parents, who told her that she would cease to be a Canadian when she turns 21.[59] However, her claim runs afoul with nationality laws of both countries.[60]

Revocation of citizenship and nullification of renunciation

Under section 10 the Act, the Minister has the power to initiate proceedings to revoke a person's Canadian citizenship or renunciation of citizenship.

Current legislation

Under subsection 10(1) of the Act, the Minister may initiate proceedings to revoke a person's citizenship or nullify the person's renunciation of citizenship if they are satisfied that the person has obtained, retained, renounced or resumed citizenship by:[61]

- "false representation" (e.g., forging the residence period in Canada);

- fraud; or,

- knowingly concealing material circumstances.

Revocation of citizenship under subsection 10(1) applies typically to naturalized Canadians. However, it may also be applied to those who had retained their citizenship. Persons whose citizenship was revoked may become stateless if they do not have citizenship or nationality of another country at the time of the final decision.[61]

Since 11 January 2018, all revocation cases must be decided by the Federal Court unless the person in question explicitly requests the Minister to make the final decision. Otherwise, the Minister no longer has the authority to unilaterally revoke a person's citizenship without going through court proceedings. However, from December 2018, citizenship officers were given "clear authority" to seize and detain any document that was deemed fraudulent, without the need of involvement of other law enforcement agencies.[62] Such documents will then be used as evidence against the person in proceedings.

After revocation, a person's status in Canada may be a Canadian citizen (for those who renounced their citizenship with fraud), a permanent resident (for those who restored or acquired citizenship with fraud), or a foreign national with no status in Canada (for other revocations). Those who become foreign nationals will be subject to deportation, while those with permanent resident status may be issued deportation orders by federal courts on the grounds of security, human rights violations, or organized crime.[61]

Previous legislation

Before 2015, revocation only applied to naturalized citizens, and the Governor in Council had to have been notified about the revocation without exception.[61]

Between 2015 and 2017, the revocation of citizenship became streamlined. More powers were vested in the Department and the Minister, who could unilaterally revoke a person's citizenship without involving the Governor in Council.[61] After the change of procedure, revocations increased nearly tenfold compared to 2014.[63]

Before 19 June 2017, subsection 10(2), as amended in 2014 by Bill C-24, included grounds for when the Minister could revoke a person's citizenship, including but not limited to:[61]

- lifetime imprisonment due to conviction for treason;

- at least five years' imprisonment due to conviction for terrorism in a Canadian court; or,

- at least five years' imprisonment due to conviction for terrorism in a foreign court.

Revocations under subsection 10(2) only applied to those with citizenship or nationality in another country.

The subsection was repealed on the day Bill C-6 received Royal Assent.[3] Zakaria Amara, a dual Jordanian-Canadian citizen whose Canadian citizenship was revoked in 2015 because of his involvement in the 2006 Ontario terrorism plot, has had his citizenship reinstated when Bill C-6 became law.[64] Amara remains the only person whose citizenship was revoked under subsection 10(2) before it was repealed.

Between 10 July 2017 and 10 January 2018, all revocation clauses in the Act were deemed inoperable until the amendments of the Act took effect on 11 January 2018. This was because in May 2017 the Federal Court had ruled in Hassouna v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) that subsections 10(1), 10(3) and 10(4) violated the Canadian Bill of Rights in a way that deprived a person's right to a fair hearing. After the suspension of the ruling had lapsed on 10 July 2017, no subsection under section 10 was enforceable until the 2017 amendments to the Act came into effect. On the same day, a federal judge had nullified the citizenship revocation of 312 people.[65]

The last part of Bill C-6, which was scheduled to take effect in 2018, included the following changes:[3]

- IRCC officers gained the power to seize all documentation relating to the investigation.

Renunciation of citizenship

A Canadian citizen who wishes to voluntarily renounce his or her citizenship for any reason must make an application directly to the federal government, and he or she ceases to be a Canadian citizen only after the federal government has approved such request. Renouncing Canadian citizenship to a foreign government (such as by taking the Oath of Allegiance to the United States) is not sufficient in itself to be considered as a voluntary renunciation of Canadian citizenship.

In general, there are two forms of renunciations: subsection 9(1) of the Act, for all renunciations, and section 7.1 of the Citizenship Regulations, for persons who acquired citizenship in 2009 and 2015 due to the changes of law.

All renunciations are subject to approval by the Governor in Council, who has the power to refuse an application on national security grounds.

General renunciation

Under subsection 9(1), a person renouncing citizenship must:[66]

- be 18 or over;

- be a citizen or national of another country;

- reside outside Canada; and

- understand the implications of renunciation.

The person may be required to attend an interview.

In some cases, the Minister may waive the residence and implication understanding requirements. A person may not renounce his or her citizenship when the revocation of citizenship is in action.[66]

Special renunciation

Section 7.1 of the Regulations provides a simpler way for those whose citizenship was restored in 2009 and 2015 to renounce their citizenship. To qualify, the applicant must have acquired or reacquired his or her citizenship under the 2009 and 2015 amendments, and:[67]

- is a citizen of another country; and

- understands the implications of renunciation.

The implication understanding requirement can also be waived by the Minister.

Persons renouncing under section 7.1 do not need to attend an interview, and there is no fee for renunciation.[67]

Resumption of Canadian citizenship

Under subsection 11(1) of the Act, a former Canadian citizen who voluntarily renounced his or her citizenship under Canadian law is generally required to satisfy a number of conditions before he or she can resume Canadian citizenship. The conditions are:[68]

- being a permanent resident;

- having physically been in Canada for no less than 365 days immediately before application; and,

- filing income taxes.

The income taxes and residence intention requirements were added on 11 June 2015 when Bill C-24 became law. The residence intention requirement, however, was repealed on 19 June 2017 when Bill C-6 received Royal Assent.[3]

Former citizens who lost their citizenship by revocation are not eligible to resume their citizenship. They must follow naturalization procedures if not permanently prohibited from doing so.[68]

Automatic mass resumption and special grants

On 17 April 2009, Bill C-37 resumed Canadian citizenship to all of those who have obtained Canadian citizenship on or after 1 January 1947 by birth or naturalization in Canada but have involuntarily lost it under the 1947 Act, and their first generation descendants born abroad were also granted Canadian citizenship on that day.

On 11 June 2015, Bill C-24 further granted citizenship for the first time to those who were born or naturalized in Canada but had lost British subject status before 1947 and their first generation descendants born abroad.[14]

On 22 September 1988, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney agreed to a redress package for Japanese-Canadians deported from Canada between 1941 and 1946 (about 4,000 in total) and their descendants. The package authorized a special grant of Canadian citizenship for any such person. All descendants of deported persons were also eligible for the grant of citizenship provided that they were living on 22 September 1988, regardless of whether the person deported from Canada was still alive.

Women who lost British subject status before 1947

Although Bill C-24 covered the majority of ex-British subjects who would have acquired citizenship in 1947, a certain number of female ex-British subjects were excluded from the Bill, mainly those born in another part of the British Empire other than Canada, had been residing in Canada long enough to qualify for citizenship under the 1947 Act, but had lost their British subject status either by marrying a foreign man before 1947, or losing British subject status when her spouse naturalized in another country. These people can acquire Canadian citizenship under subsection 11(2) of the 1977 Act by a simple declaration made to the IRCC. There are no additional requirements other than the declaration.[69]

Multiple citizenship

The attitude toward multiple citizenship in Canada has changed significantly over time. Between 1 January 1947 and 14 February 1977, multiple citizenship was only allowed under limited circumstances. On 15 February 1977, the restrictions on multiple citizenship ended.

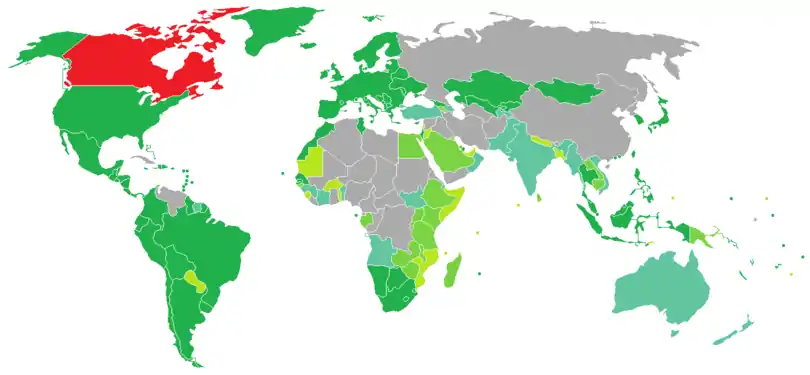

The number of Canadians with multiple citizenship is difficult to determine because of the changes in Canadian and foreign laws. In 2006, around 863,000 Canadian citizens residing in Canada reported in census to hold at least one more citizenship or nationality of another country.[70] The actual figure, however, is substantially higher, as the federal government does not maintain statistics on persons with multiple citizenship who reside abroad. The en masse citizenship grant and restoration in 2009 and 2015 further increased the number of Canadians with multiple citizenship, as Canadian citizenship was restored or granted to most of the people who lost their Canadian citizenship or British subject status by acquiring citizenship of another country. These people, as well as their descendants, are de jure Canadians with multiple citizenship even when they do not exercise citizenship rights (e.g., travelling on a Canadian passport).

Although not a legal requirement, Canadian citizens with multiple citizenship are required to carry a Canadian passport when boarding their flights to Canada since November 2016 unless they are dual Canadian-American citizens carrying a valid United States passport. This is caused by the amended visa policy, which imposed a pre-screening requirement on visa-exempt nationalities.[71] Those entering Canada by land or sea are not subject to this restriction.

Under the current Act and its amendments

The 1977 Act removed all restrictions on multiple citizenship and Canadian citizens acquiring another citizenship on or after 15 February 1977 would no longer lose their Canadian citizenship.

Those who lost their Canadian citizenship or British subject status under the 1947 Act or the British 1914 Act regained or gained Canadian citizenship in 2009 and 2015, respectively. The grant and resumption under Bill C-37 and Bill C-24 included these people's children.

Under the 1947 Act

Although multiple citizenship was severely restricted under the 1947 Act, it was still possible to be a citizen of Canada and another country so long as the acquisition of the other citizenship or nationality is involuntary. A person may involuntarily acquire citizenship of another country when:[50][27]

- they were born in a country with jus soli citizenship law and they were also registered as a Canadian citizen (e.g., the United States);

- they became a citizen of another country because of a change of law in that country (e.g., on 1 January 1949 the United Kingdom conferred Citizenship of the United Kingdom and Colonies, or CUKC status, on any person born in the United Kingdom, and these people later became British citizens in 1983);

- they acquired the other citizenship by formal marriage to a foreign man (e.g., Italy prior to 1983);

- they were naturalized as a Canadian citizen and did not lose their foreign citizenship under their own country's nationality law (e.g., New Zealand).

Before 1947

Like peoples of all other British colonies and Dominions at the time, those born in Canada before 1947 were British subjects by nationality under the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914. The term "Canadian citizen", however, was first created under the Immigration Act 1910 to identify a British subject who was born in Canada or who possessed Canadian domicile, which could be acquired by any British subject who had lawfully resided in Canada for at least three years.[72] At that time, "Canadian citizenship" was solely an immigration term and not a nationality term, hence "Canadian citizens" under the Immigration Act would be subject to the same rules on acquisition and loss of British subject status under the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914.[73] Under the Immigration Act 1910, "Canadian citizenship" would be lost for any person who had ceased to be a British subject, as well as non-Canadian born or naturalized British subjects who "voluntarily [reside] outside Canada".[72] While the former would lose "Canadian citizenship" and British subject status simultaneously, the latter would only stop being a "Canadian citizen". Canadian-born or naturalized British subjects would not lose their Canadian domicile by residing outside Canada.

The only circumstance in which a British subject could acquire de jure dual citizenship was by birth to a British subject father in a country which offered birthright citizenship (e.g., the United States).[74] However, "Canadian citizens" may acquire de facto dual citizenship by residing in another British Dominion, protectorate, or colony, as they would simultaneously have "Canadian citizenship" and, if residing long enough to meet the requirements, the domicile of that Dominion, protectorate, or colony.

To further separate British subjects domiciled in Canada from other British subjects, the term "Canadian National" was created by the Canadian Nationals Act 1921 on 3 May of that year. The status was bestowed on all holders of "Canadian citizenship" and their wives, but also included all children born outside Canada to Canadian National fathers, regardless of whether possessing British subject status at the time of birth. This 1921 Act also provided a path for certain Canadian Nationals who were born outside Canada, or who were born in Canada but had the domicile of the United Kingdom or another Dominion at birth or as a minor, to relinquish their Canadian Nationality and domicile.[75] Before the passage of the 1921 Act, "Canadian citizens" who were born in Canada had no course to abandon their Canadian domicile without having to relinquish their British subject status altogether. As Canadian Nationality was also independent of their British subject status, the renunciation under the 1921 Act would not affect their British subject status, although they would also not become Canadian citizens on 1 January 1947 when it was first created.

The Royal Family

Though she resides predominantly in the United Kingdom and it is uncertain whether a monarch is subject to his or her own citizenship laws,[76] the Queen of Canada is considered Canadian.[76][77][78] She and those others in the Royal Family who do not meet the requirements of Canadian citizenship (there are five Canadian citizens within the Royal Family) are not classified by either the government or some constitutional experts as foreigners to Canada;[79][80] in the Canadian context, members of the Royal Family are subjects specifically of the monarch of Canada.[81][82]

The Department of National Defence, in its Honours, Flags and Heritage Structure of the Canadian Forces manual, separates the monarch of Canada and Canadian Royal Family from "foreign sovereigns and members of reigning foreign families, [and] heads of state of foreign countries..."[83] Further, in 2013, the constitution of the Order of Canada was changed so as to add, along with the pre-existing "substantive" (for Canadian citizens only) and "honorary" (for foreigners only), a new category of "extraordinary" to the order's three grades, available only to members of the Royal Family and governors general.[84]

Members of the Royal Family have also, on occasion, declared themselves to be Canadian and called Canada "home."[76] Princess Elizabeth, Duchess of Edinburgh, said in 1951 that, when in Canada, she was "amongst fellow countrymen."[85][86] In 1983, before departing the US for Canada, now-Queen Elizabeth said "I'm going home to Canada tomorrow."[87] Likewise, in 2005, she said she agreed with the statement earlier made by her mother, Queen Elizabeth, that Canada felt like a "home away from home."[88] Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, refused honorary appointment to the Order of Canada on the grounds that, as the royal consort of the Queen, he was Canadian, and thus entitled to a substantive appointment.[89]

Judicial review of Citizenship Act provisions

Definition of "residence requirement"

There have been a number of court decisions dealing with the subject of Canadian citizenship. In particular, the interpretation of the 3-year (1,095-day) residence requirement enacted by the 1977 Citizenship Act, which does not define the term "residence" and, further, prohibits an appeal of a Federal Court decision in a citizenship matter to the Federal Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court, has "led to a great deal of mischief and agony"[90] and generated considerable judicial controversy.

Over the years two principal schools of thought with respect to residence have emerged from the Federal Court.

Early on, Associate Chief Justice Arthur L. Thurlow in Papadogiorgakis (Re), [1978] 2 F.C. 208,[91] opined that residency entails more than a mere counting of days. He held that residency is a matter of the degree to which a person, in mind or fact, settles into or maintains or centralizes his or her ordinary mode of living, including social relations, interests and conveniences. The question becomes whether an applicant's linkages suggest that Canada is his or her home, regardless of any absences from the country.

In Re Koo,[92] Justice Barbara Reed further elaborated that in residency cases the question before the Court is whether Canada is the country in which an applicant has centralized his or her mode of existence. Resolving such a question involves consideration of several factors:

- Was the individual physically present in Canada for a long period prior to recent absences which occurred immediately before the application for citizenship?

- Where are the applicant's immediate family and dependents (and extended family) resident?

- Does the pattern of physical presence in Canada indicate a returning home or merely visiting the country?

- What is the extent of the physical absences—if an applicant is only a few days short of the 1095-day total it is easier to find deemed residence than if those absences are extensive?

- Is the physical absence caused by a clearly temporary situation such as employment as a missionary abroad, following a course of study abroad as a student, accepting temporary employment abroad, accompanying a spouse who has accepted temporary employment abroad?

- What is the quality of the connection with Canada: is it more substantial than that which exists with any other country?

The general principle is that the quality of residence in Canada must be more substantial than elsewhere.

In contrast, a line of jurisprudence flowing from the decision in Re Pourghasemi (1993), 62 F.T.R. 122, 19 Imm. L.R. (2d) 259, emphasized how important it is for a potential new citizen to be immersed in Canadian society and that a person cannot reside in a place where the person is not physically present. Thus, it is necessary for a potential citizen to establish that he or she has been physically present in Canada for the requisite period of time.

In the words of Justice Francis Muldoon:

It is clear that the purpose of paragraph 5(1)(c) is to ensure that everyone who is granted precious Canadian citizenship has become, or at least has been compulsorily presented with the everyday opportunity to become "Canadianized." This happens by "rubbing elbows" with Canadians in shopping malls, corner stores, libraries, concert halls, auto repair shops, pubs, cabarets, elevators, churches, synagogues, mosques and temples – in a word wherever one can meet and converse with Canadians – during the prescribed three years. One can observe Canadian society for all its virtues, decadence, values, dangers and freedoms, just as it is. That is little enough time in which to become Canadianized. If a citizenship candidate misses that qualifying experience, then Canadian citizenship can be conferred, in effect, on a person who is still a foreigner in experience, social adaptation, and often in thought and outlook... So those who would throw in their lot with Canadians by becoming citizens must first throw in their lot with Canadians by residing among Canadians, in Canada, during three of the preceding four years, in order to Canadianize themselves. It is not something one can do while abroad, for Canadian life and society exist only in Canada and nowhere else.

The co-existence of such disparate, yet equally valid approaches has led some judges to comment that:

- the "[citizenship] law is in a sorry state;"[93]

- "there cannot be two correct interpretations of a statute;"[94]

- "it does not engender confidence in the system for conferring citizenship if an applicant is, in the course of a single application, subjected to different legal tests because of the differing legal views of the Citizenship Court;"[95]

- there's a "scandalous incertitude in the law;"[96] and that

- "there is no doubt that a review of the citizenship decisions of this Court, on that issue, demonstrates that the process of gaining citizenship in such circumstances is akin to a lottery."[97]

In 2010, it seemed that a relative judicial consensus with respect to decision-making in residence cases might emerge. In several Federal Court decisions it was held that the citizenship judge must apply a hybrid two-test approach by firstly ascertaining whether, on the balance of probabilities, the applicant has accumulated 1,095 days of physical presence. If so, the residency requirement is considered to have been met. If not, then the judge must additionally assess the application under the "centralized mode of existence" approach, guided by the non-exhaustive factors set out in Koo (Re).[98][99][100]

However, most recently, this compromise formula was rejected by Federal Court judges, who continued to plead for legislative intervention as the means to settle the residency requirement debacle.[101][102][103]

Other significant cases

| Case | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Glynos v. Canada,* 1992 | [104] | The Federal Court of Appeal ruled that the child of a Canadian mother had the right to be granted Canadian citizenship, despite one of the parents responsible (i.e. the father) having been naturalized as a U.S. citizen before 15 February 1977 and thus renouncing his Canadian citizenship.[104]:56–9 |

| Benner v. Canada (Secretary of State), 1997 | [105] | The Supreme Court ruled that children born of Canadian mothers abroad prior to 15 February 1977 were to be treated the same as those of Canadian fathers (i.e., granted citizenship upon application without the requirements of a security check or Oath of Citizenship). |

| Canada (Attorney General) v. McKenna, 1998 | [106] | The Federal Court of Appeal ruled that the Minister must establish a bona fide justification pursuant to § 15(g) of the Canadian Human Rights Act[107] regarding the discriminatory practice on adoptive parentage. More specifically, a child born abroad to Canadian citizens would obtain "automatic" citizenship whereas a child adopted abroad must gain admission to Canada as permanent residents, as mandated by paragraph 5(2)(a) of the Citizenship Act, which incorporates, by reference, the requirements imposed by the Immigration Act pertaining to permanent resident status.

However, this case also declared that the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal had (a) overreached itself in declaring that the granting of citizenship was a service customarily available to the general public; and (b) breached the rules of natural justice by failing to notify the Minister that the provisions of the Citizenship Act were being questioned. After the amendment in 2007, most adopted persons now automatically acquire citizenship after the finalization of adoption, even if the adoption itself took place prior to the amendment, as the previous ruling is no longer relevant. |

| Taylor v. Canada,* 2007 | [108] | In September 2006, the Federal Court had ruled that an individual born abroad and out of wedlock to a Canadian serviceman father and a non-Canadian mother acquired citizenship upon arrival in Canada after World War II without having subsequently lost their citizenship whilst living abroad.[108]

In November 2007, this was reversed by the Federal Court of Appeal, holding that the pursuant (Taylor) had lost his Canadian citizenship under § 20 of the 1947 Act (i.e., absence from Canada for 10 consecutive years), and therefore the court could not grant his request. However, he was now able to request a grant of citizenship under §5(4) of the current Act (i.e., special cases). Citizenship was subsequently granted to Taylor in December 2007.[109] |

| Canada** v. Dufour, 2014 | [110] | The Federal Court of Appeal ruled that the citizenship officer cannot unreasonably deny a person's citizenship application made under paragraph 5.1(3) if the Quebec government had fully validated the person's adoption. Moreover, in order to render a Quebec adoption as an adoption of convenience, the officer must prove, with tangible evidence, that the Quebec legal system was defrauded by the citizenship applicant.

The respondent, Burou Jeanty Dufour, a Haitian citizen who was adopted by a Quebec man, was deemed as an adoptee by convenience. Dufour was thus denied citizenship under paragraph 5.1(3)(b) after a citizenship officer found that (a) his adoption was not approved by the appropriate department within the Haitian government; and (b) Dufour arrived in Canada on a visitor's visa instead of a permanent resident visa, even when his adoption was later approved by a Quebec court. The Court of Appeal believed that the officer had failed to validate the genuineness of the adoption by failing to correspond with the relevant Quebec authorities. Hence, there was no evidence to prove that the adoption was indeed an adoption of convenience. |

| Canada** v. Kandola, 2014 | [111] | The Federal Court of Appeal clarified that for a child to be considered a Canadian citizen by descent, a genetic link must be proven to the Canadian parent through a DNA test. In this case, a person who was born to a Canadian citizen father outside of Canada with assisted human reproduction (AHR) technology, but with no genetic links to the father, was declared not to be a Canadian citizen by descent. |

| Hassouna v. Canada,** 2017 | [112] | The Federal Court of Canada ruled in a judicial review that §§ 10(1), 10(3), and 10(4) of the Act—all regarding revocation of citizenship—violated § 2(e) of the Canadian Bill of Rights in a way that "[deprived] a person of the right to a fair hearing in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice for the determination of his rights and obligations," due to the fact that those who had their citizenship revoked under these subsections did not have a right to present their cases to the court.

All eight applicants' revocation notices were quashed, and the three subsections of the Act are deemed inoperable as of 10 July 2017 after the suspension of the ruling has expired until their formal repeal on 11 January 2018, when revocation is now a matter of the Federal Court, whereafter the Minister can no longer make unilateral decisions. |

| Vavilov v. Canada,** 2017 | [113] | The Federal Court of Appeal and, later, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) ruled that children born in Canada to a parent who is employed by a foreign government, but is not recognized by Global Affairs Canada as an employee of a foreign government, are Canadian citizens by birth and are not subject to the exceptions under § 3(2). This would be because only employees of foreign governments with "diplomatic privileges and immunities certified by the Minister of Foreign Affairs" are exempted from the jus soli rule.

The appellant, Vavilov, a man who was born in Canada to Russian sleeper agents, was previously declared not to be a Canadian citizen by the Federal Court, as his parents, who were arrested in a 2010 crackdown of Russian agents in the US, were employees of a foreign government at the time of his birth. Moreover, none of his parents were ever Canadian citizens since they only assumed the identities of two deceased Canadians.[114] On 10 May 2018, the federal government's leave to appeal was granted by the SCC, who would examine whether the man and his elder brother, who won a similar case in April that year, would fall under § 3(2) of the Act.[115] On 19 December 2019, the SCC ruled in Alex and Timothy Vavilov's favour and affirmed their status as Canadian citizens.[21][116][117] |

| Halepota v. Canada,** 2018 | [118] | The Federal Court ruled that exceptional service to the United Nations (UN) and its agencies is considered as "service of exceptional value to Canada" just as well, due to Canada's UN membership.

In this case, a senior-level IRCC decision-maker determined that the appellant, Halepota, a permanent resident and a senior director of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), was ineligible for naturalization under § 5(4) as she had made no notable contribution to Canada "for the purposes of granting Canadian citizenship." Though her work was "commendable" and "aligns with Canada’s humanitarian assistance mandate," it was noted that the majority of her work with the UNHCR was done outside of Canada. However, the judge ruled that, due to Canada's commitment to the mandate and goals of the UN, exceptional services to the UN must be considered as exceptional service to Canada for citizenship applications. As a result, the court quashed the decision-maker's decision and the application was sent to another decision-maker for consideration with respective to the ruling. |

| *Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration); **Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) | ||

Rights, responsibilities, and privileges of citizens

In addition to the rights afforded to people in Canada in general, Canadian citizens are granted additional rights, which are inaccessible to permanent residents (PRs) or otherwise.[119] Permanent residents, however, have the same ability as a Canadian citizens to petition to receive a grant of armorial bearings.[120]

Along with the exclusive privileges granted to them, Canadian citizens must also take the responsibility of completing jury duty when called to do so, and failure to respond or appear may warrant legal consequences. Permanent residents, on the other hand, are legally ineligible to serve as jurors and, hence, are not required to do so.[121]

Some of the exclusive privileges afforded to Canadian citizens include the right to:[119]

- obtain a Canadian passport for travel and to seek consular protection when outside Canada, including full consular services offered by Australia under the Canada–Australia Consular Services Sharing Agreement in certain countries without a Canadian mission. In contrast, permanent residents are ineligible for a Canadian passport and must travel with passports issued by their country of nationality. They are also not entitled to consular services and must seek protection from their country of nationality.

- live outside of Canada indefinitely while retaining the right to return to Canada. In comparison, one may lose their permanent residency if the Immigration and Refugee Board has determined that a PR did not meet the residency obligation in Canada.

- pass on Canadian citizenship to children born outside Canada (first generation only). In contrast, children of permanent residents must first apply to immigrate to Canada in order to reside in Canada.

- avoid deportation from within Canada. Contrastly, permanent residents may be subject to deportation orders for violating Canadian laws.