Eiger

The Eiger is a 3,967-metre (13,015 ft) mountain of the Bernese Alps, overlooking Grindelwald and Lauterbrunnen in the Bernese Oberland of Switzerland, just north of the main watershed and border with Valais. It is the easternmost peak of a ridge crest that extends across the Mönch to the Jungfrau at 4,158 m (13,642 ft), constituting one of the most emblematic sights of the Swiss Alps. While the northern side of the mountain rises more than 3,000 m (10,000 ft) above the two valleys of Grindelwald and Lauterbrunnen, the southern side faces the large glaciers of the Jungfrau-Aletsch area, the most glaciated region in the Alps. The most notable feature of the Eiger is its nearly 1,800-metre-high (5,900 ft) north face of rock and ice, named Eiger-Nordwand, Eigerwand or just Nordwand, which is the biggest north face in the Alps.[3] This huge face towers over the resort of Kleine Scheidegg at its base, on the homonymous pass connecting the two valleys.

| Eiger | |

|---|---|

The north face of the Eiger | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,967 m (13,015 ft) |

| Prominence | 362 m (1,188 ft) [1] |

| Parent peak | Mönch |

| Isolation | 2.0 km (1.2 mi) [2] |

| Listing | Great north faces of the Alps Alpine mountains above 3000 m |

| Coordinates | 46°34′39″N 8°0′19″E |

| Naming | |

| English translation | Ogre |

| Geography | |

Eiger Location in Switzerland | |

| Location | Canton of Bern, Switzerland |

| Parent range | Bernese Alps |

| Topo map | Swisstopo 1229 Grindelwald |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Limestone |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 11 August 1858 |

| Easiest route | basic rock/snow/ice climb (AD) |

The first ascent of the Eiger was made by Swiss guides Christian Almer and Peter Bohren and Irishman Charles Barrington, who climbed the west flank on August 11, 1858. The north face, the "last problem" of the Alps, considered amongst the most challenging and dangerous ascents, was first climbed in 1938 by an Austrian-German expedition.[4] The Eiger has been highly publicized for the many tragedies involving climbing expeditions. Since 1935, at least sixty-four climbers have died attempting the north face, earning it the German nickname Mordwand, literally "murder(ous) wall"—a pun on its correct title of Nordwand (North Wall).[5]

Although the summit of the Eiger can be reached by experienced climbers only, a railway tunnel runs inside the mountain, and two internal stations provide easy access to viewing-windows carved into the rock face. They are both part of the Jungfrau Railway line, running from Kleine Scheidegg to the Jungfraujoch, between the Mönch and the Jungfrau, at the highest railway station in Europe. The two stations within the Eiger are Eigerwand (behind the north face) and Eismeer (behind the south face), at around 3,000 metres. Since 2016 the Eigerwand station is not regularly served any more.

Etymology

The first mention of Eiger, appearing as "mons Egere", was found in a property sale document of 1252, but there is no clear indication of how exactly the peak gained its name.[6] The three mountains of the ridge are commonly referred to as the Virgin (German: Jungfrau – translates to "virgin" or "maiden"), the Monk (Mönch), and the Ogre (Eiger; the standard German word for ogre is Oger). The name has been linked to the Latin term acer, meaning "sharp" or "pointed".

Geographic setting and description

The Eiger is located above the Lauterbrunnen Valley to the west and Grindelwald to the north in the Bernese Oberland region of the canton of Bern.[7] It forms a renowned mountain range of the Bernese Alps together with its two companions: the Jungfrau (4,158 m (13,642 ft)) about 5.6 kilometres (3.5 mi) southwest of it and the Mönch (4,107 m (13,474 ft)) about in the middle of them.[8] The nearest settlements are Grindelwald, Lauterbrunnen (795 m (2,608 ft)) and Wengen (1,274 m (4,180 ft)). The Eiger has three faces: north (or more precisely NNW), east (or more precisely ESE), and west (or more precisely WSW). The northeastern ridge from the summit to the Ostegg (lit.: eastern corner, 2,709 m (8,888 ft)), called Mittellegi, is the longest on the Eiger. The north face overlooks the gently raising Alpine meadow between Grindelwald (943 m (3,094 ft)) and Kleine Scheidegg (2,061 m (6,762 ft)), a mountain railways junction and a pass, which can be reached from both sides, Grindelwald and Lauterbrunnen/Wengen – by foot or train.[7]

Politically, the Eiger (and its summit) belongs to the Bernese municipalities of Grindelwald and Lauterbrunnen. The Kleine Scheidegg (literally, the small parting corner) connects the Männlichen-Tschuggen range with the western ridge of the Eiger.[7] The Eiger does not properly form part of the main chain of the Bernese Alps, which borders the canton of Valais and forms the watershed between the Rhine and the Rhône, but constitutes a huge limestone buttress, projecting from the crystalline basement of the Mönch across the Eigerjoch. Consequently, all sides of the Eiger feed finally the same river, namely the Lütschine.[7]

Eiger's water is connected through the Weisse Lütschine (the white one) in the Lauterbrunnen Valley on the west side (southwestern face of the Eiger), and through the Schwarze Lütschine (the black one) running through Grindelwald (northwestern face), which meet each other in Zweilütschinen (lit.: the two Lütschinen) where they form the proper Lütschine.[7] The east face is covered by the glacier called Ischmeer, (Bernese German for Ice Sea), which forms one upper part of the fast-retreating Lower Grindelwald Glacier. These glaciers' water forms a short creek, which is also confusingly called the Weisse Lütschine, but enters the black one already in Grindelwald together with the water from the Upper Grindelwald Glacier.[7] Therefore, all the water running down the Eiger converges at the northern foot of the Männlichen (2,342 m (7,684 ft)) in Zweilütschinen (654 m (2,146 ft)), about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) northwest of the summit, where the Lütschine begins its northern course to Lake Brienz and the Aare (564 m (1,850 ft)).[7]

Although the north face of the Eiger is almost free of ice, significant glaciers lie at the other sides of the mountain. The Eiger Glacier flows on the southwestern side of the Eiger, from the crest connecting it to the Mönch down to 2,400 m (7,900 ft), south of Eigergletscher railway station, and feeds the Weisse Lütschine through the Trümmelbach. On the east side, the Ischmeer–well visible from the windows of Eismeer railway station–flows eastwards from the same crest then turns to the north below the impressive wide Fiescherwand, the north face of the Fiescherhörner triple summit (4,049 m (13,284 ft)) down to about 1,600 m (5,200 ft) of the Lower Grindelwald Glacier system.[7]

The massive composition of the Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau constitutes an emblematic sight of the Swiss Alps and is visible from many places on the Swiss Plateau and the Jura Mountains in the northwest. The higher Finsteraarhorn (4,270 m (14,010 ft)) and Aletschhorn (4,190 m (13,750 ft)), which are located about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) to the south, are generally less visible and situated in the middle of glaciers in less accessible areas. As opposed to the north side, the south and east sides of the range consist of large valley glaciers extending for up to 22 kilometres (14 mi), the largest (beyond the Eiger drainage basin) being those of Grand Aletsch, Fiesch, and Aar Glaciers, and is thus uninhabited. The whole area, the Jungfrau-Aletsch protected area, comprising the highest summits and largest glaciers of the Bernese Alps, was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001.[7]

In July 2006, a piece of the Eiger, amounting to approximately 700,000 cubic metres of rock, fell from the east face. As it had been noticeably cleaving for several weeks and fell into an uninhabited area, there were no injuries and no buildings were hit.[9]

North face

The Nordwand, German for "north wall" or "north face," is the north face of the Eiger (also known as the Eigernordwand: "Eiger north wall" or Eigerwand). It is one of the three great north faces of the Alps, along with the north faces of the Matterhorn and the Grandes Jorasses (known as 'the Trilogy') and also one of the biggest sheer face in Europe, between 1,600 m and 1,800 m (over a mile) high.[3] The face overlooks Kleine Scheidegg and the valley of Grindelwald. At 2,866 metres inside the mountain lies the Eigerwand railway station. The station is connected to the north face by a tunnel opening at the face, which has sometimes been used to rescue climbers. The Eiger Trail, at the base of the north face, runs from Eigergletscher to Alpiglen railway stations. The approach hike to the base of the face takes less than an hour from Eigergletscher.

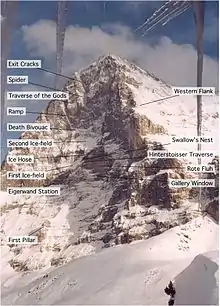

Some of the notable features on the north face are (from the bottom): First Pillar, Eigerwand Station, First Ice-field, Hinterstoisser Traverse, Swallow's Nest, Ice Hose, Second Ice-field, Death Bivouac, Ramp, Traverse of the Gods, Spider and Exit Cracks.

In 1938, Alpine Journal editor Edward Lisle Strutt calls the face "an obsession for the mentally deranged" and "the most imbecile variant since mountaineering first began."[10] In the same year, however, the north face was finally climbed on 24 July by Andreas Heckmair, Ludwig Vörg, Heinrich Harrer and Fritz Kasparek, a German–Austrian group. The group had originally consisted of two independent teams; Harrer and Kasparek were joined on the face by Heckmair and Vörg, who had started their ascent a day later and had been helped by the fixed rope that the lead group had left across the Hinterstoisser Traverse. The two groups, led by the experienced Heckmair, cooperated on the more difficult later pitches, and finished the climb roped together as a single group of four.

A portion of the upper face is called "The White Spider", as snow-filled cracks radiating from an ice-field resemble the legs of a spider. Harrer used this name for the title of his book about his successful climb, Die Weisse Spinne (translated into English as The White Spider: The Classic Account of the Ascent of the Eiger). During the first successful ascent, the four men were caught in an avalanche as they climbed the Spider, but all had enough strength to resist being swept off the face.

Since then, the north face has been climbed many times. Today it is regarded as a formidable challenge, not only because of its technical difficulties, exceeding those of some of the 8,000 m peaks in the Himalaya and Karakoram, but also because of the increased rockfall and diminishing ice-fields.[11] Climbers are increasingly electing to challenge the Eiger in winter, when the crumbling face is strengthened by ice.

Since 1935, at least sixty-four climbers have died attempting the north face, earning it the German nickname, Mordwand, or "murderous wall", a play on the face's German name Nordwand.[5]

Climbing history

While the summit was reached without much difficulty in 1858 by a complex route on the west flank, the battle to climb the north face has captivated the interest of climbers and non-climbers alike. Before it was successfully climbed, most of the attempts on the face ended tragically and the Bernese authorities even banned climbing it and threatened to fine any party that should attempt it again. But the enthusiasm which animated the young talented climbers from Austria and Germany finally vanquished its reputation of unclimbability when a party of four climbers successfully reached the summit in 1938 by what is known as the "1938" or "Heckmair" route.

The climbers that attempted the north face could be easily watched through the telescopes from the Kleine Scheidegg, a pass between Grindelwald and Lauterbrunnen, connected by rail. The contrast between the comfort and civilization of the railway station and the agonies of the young men slowly dying a short yet uncrossable distance away led to intensive coverage by the international media.

After World War II, the north face was climbed twice in 1947, first by a party of two French guides, Louis Lachenal and Lionel Terray, then by a Swiss party consisting of H. Germann, with Hans and Karl Schlunegger.[12]

First ascent

In 1857, a first attempt was made by Christian Almer, Christian Kaufmann, Ulrich Kaufmann guiding the Austrian alpinist Sigismund Porges. They did manage the first ascent of neighboring Mönch instead. Porges, however, successfully made the second ascend of the Eiger in July 1861 with the guides Christian Michel, Hans and Peter Baumann.[13]

The first ascent was made by the western flank on August 11, 1858 by Charles Barrington with guides Christian Almer and Peter Bohren. On the previous afternoon, the party walked up to the Wengernalp hotel. From there they started the ascent of the Eiger at 3:30 a.m. Barrington describes the route much as it is followed today, staying close to the edge of the north face much of the way. They reached the summit at about noon, planted a flag, stayed for some 10 minutes and descended in about four hours. Barrington describes the reaching of the top, saying, "the two guides kindly gave me the place of first man up." After the descent, the party was escorted to the Kleine Scheidegg hotel, where their ascent was confirmed by observation of the flag left on the summit. The owner of the hotel then fired a cannon to celebrate the first ascent. According to Harrer's The White Spider, Barrington was originally planning to make the first ascent of the Matterhorn, but his finances did not allow him to travel there as he was already staying in the Eiger region.[14]

Mittellegi ridge

Although the Mittellegi ridge had already been descended by climbers (since 1885) with the use of ropes in the difficult sections, it remained unclimbed until 1921. On the 10th of September of that year, Japanese climber Yuko Maki, along with Swiss guides Fritz Amatter, Samuel Brawand and Fritz Steuri made the first successful ascent of the ridge. The previous day, the party approached the ridge from the Eismeer railway station of the Jungfrau Railway and bivouacked for the night. They started the climb at about 6:00 a.m. and reached the summit of the Eiger at about 7:15 p.m., after an over 13 hours gruelling ascent. Shortly after, they descended the west flank. They finally reached Eigergletscher railway station at about 3:00 a.m. the next day.[15]

1935

In 1935 two young German climbers from Bavaria, Karl Mehringer and Max Sedlmeyer, arrived at Grindelwald to attempt to climb the face. They waited a long time for good weather and when the clouds finally cleared they started. The two climbers reached the height of the Eigerwand station and made their first bivouac. On the following day, because of the greater difficulties, they gained little height. On the third day they made hardly any vertical ground. That night a storm broke and the mountain was hidden in fog, and then it began to snow. Avalanches of snow began to sweep the face and the clouds closed over it. Two days later, there was a short moment when the clouds cleared and the mountain was visible for a while. The two men were glimpsed, now a little higher and about to bivouac for the fifth time. Then the fog came down again and hid the climbers. A few days later the weather finally cleared, revealing a completely white north face. The two climbers were found later frozen to death at 3,300 m, at a place now known as "Death Bivouac".[12][16]

1936

The next year ten young climbers from Austria and Germany came to Grindelwald and camped at the foot of the mountain. Before their attempts started one of them was killed during a training climb, and the weather was so bad during that summer that, after waiting for a change and seeing none on the way, several members of the party gave up. Of the four that remained, two were Bavarians, Andreas Hinterstoisser and Toni Kurz, and two were Austrians, Willy Angerer and Edi Rainer. When the weather improved they made a preliminary exploration of the lowest part of the face. Hinterstoisser fell 37 metres (121 ft) but was not injured. A few days later the four men finally began the ascent of the face. They climbed quickly, but on the next day, after their first bivouac, the weather changed; clouds came down and hid the group to the observers. They did not resume the climb until the following day, when, during a break, the party was seen descending, but the climbers could be seen only intermittently from the ground. The group had no choice but to retreat, since Angerer had suffered serious injuries from falling rock. The party became stuck on the face when they could not recross the difficult Hinterstoisser Traverse, from which they had taken the rope they had first used to climb it. The weather then deteriorated for two days. They were ultimately swept away by an avalanche, which only Kurz survived, hanging on a rope. Three guides started on an extremely perilous rescue attempt. They failed to reach him but came within shouting distance and learned what had happened. Kurz explained the fate of his companions: one had fallen down the face, another was frozen above him, and the third had fractured his skull in falling and was hanging dead on the rope.[12]

In the morning the three guides came back, traversing the face from a hole near the Eigerwand station and risking their lives under incessant avalanches. Toni Kurz was still alive but almost helpless, with one hand and one arm completely frozen. Kurz hauled himself off the cliff after cutting loose the rope that bound him to his dead teammate below and climbed back onto the face. The guides were not able to pass an unclimbable overhang that separated them from Kurz. They managed to give him a rope long enough to reach them by tying two ropes together. While descending, Kurz could not get the knot to pass through his carabiner. He tried for hours to reach his rescuers who were only a few metres below him. Then he began to lose consciousness. One of the guides, climbing on another's shoulders, was able to touch the tip of Kurz's crampons with his ice-axe but could not reach higher. Kurz was unable to descend further and, completely exhausted, died slowly.[12]

1937

An attempt was made in 1937 by Mathias Rebitsch and Ludwig Vörg. Although the attempt was unsuccessful, they were nonetheless the first climbers who returned alive from a serious attempt on the face. They started the climb on 11 August and reached a high point of a few rope lengths above Death Bivouac. A storm then broke and after three days on the wall they had to retreat. This was the first successful withdrawal from a significant height on the wall.[17]

First ascent of the north face

The north face was first climbed on July 24, 1938 by Anderl Heckmair, Ludwig Vörg, Heinrich Harrer and Fritz Kasparek in a German–Austrian party. The party had originally consisted of two independent teams: Harrer (who did not have a pair of crampons on the climb) and Kasparek were joined on the face by Heckmair and Vörg, who had started their ascent a day later and had been helped by the fixed rope that the lead team had left across the Hinterstoisser Traverse. The two groups, led by the experienced Heckmair, decided to join their forces and roped together as a single group of four. Heckmair later wrote: "We, the sons of the older Reich, united with our companions from the Eastern Border to march together to victory."[12]

The expedition was constantly threatened by snow avalanches and climbed as quickly as possible between the falls. On the third day a storm broke and the cold was intense. The four men were caught in an avalanche as they climbed "the Spider," the snow-filled cracks radiating from an ice-field on the upper face, but all possessed sufficient strength to resist being swept off the face. The members successfully reached the summit at four o'clock in the afternoon. They were so exhausted that they only just had the strength to descend by the normal route through a raging blizzard.[12]

Other notable events

- 1864 (Jul 27): Fourth ascent, and first ascent by a woman, Lucy Walker, who was part of a group of six guides (including Christian Almer and Melchior Anderegg) and five clients, including her brother Horace Walker[13]

- 1871: First ascent by the southwest ridge, 14 July (Christian Almer, Christian Bohren, and Ulrich Almer guiding W. A. B. Coolidge and Meta Brevoort).

- 1890: First ascent in winter, Ulrich Kaufmann and Christian Jossi guiding C. W. Mead and G. F. Woodroffe.

- 1924: First ski ascent and descent via the Eiger glacier by Englishman Arnold Lunn and the Swiss Fritz Amacher, Walter Amstutz and Willy Richardet.

- 1932: First ascent of the northeast face ("Lauper route") by Hans Lauper, Alfred Zürcher, Alexander Graven and Josef Knubel[13]

- 1970: First ski descent over the west flank, by Sylvain Saudan.

- 1986: Welshman Eric Jones becomes the first person to BASE jump from the Eiger.

- 1988: Original Route (ED2), north face, Eiger (3970m), Alps, Switzerland, first American solo (nine and a half hours) by Mark Wilford.[18]

- 1991: First ascent, Metanoia Route, North Face, solo, winter, without bolts, Jeff Lowe.

- 1992 (18 July): Three BMG/UIAGM/IFMGA clients died in a fall down the West Flank: Willie Dunnachie; Douglas Gaines; and Phillip Davies. They had ascended the mountain via the Mittellegi Ridge.

- 2006 (14 June): François Bon and Antoine Montant make the first speedflying descent of the Eiger.[19][20]

- 2006 (15 July): Approximately 700,000 cubic metres (20 million cubic feet) of rock from the east side collapses. No injuries or damage were reported.[21]

- 2015 (23 July): A team of British Para-Climbers reached the summit via the West Flank Route. The team included John Churcher, the world's first blind climber to summit the Eiger, sight guided by the team leader Mark McGowan. Colin Gourlay enabled the ascent of other team members, including Al Taylor who has multiple sclerosis, and the young autistic climber Jamie Owen from North Wales. The ascent was filmed by the adventure filmmakers Euan Ryan & Willis Morris of Finalcrux Films.

Books and films

- The 1959 book The White Spider by Heinrich Harrer describes the first successful ascent of the Eiger north face.

- Eiger Direct, 1966, by Dougal Haston and Peter Gillman, London: Collins, also known as Direttissima; the Eiger Assault

- The 1971 novel The Ice Mirror by Charles MacHardy describes the second attempted ascent of the Eiger north face by the main character.[22][23]

- The 1972 novel The Eiger Sanction is an action/thriller novel by Rodney William Whitaker (writing under the pseudonym Trevanian), based around the climbing of the Eiger. This was then made into a 1975 film starring Clint Eastwood and George Kennedy. The Eiger Sanction film crew included very experienced mountaineers (e.g., John Cleare, Dougal Haston, and Hamish MacInnes, see Summit, 52, Spring 2010) as consultants, to ensure accuracy in the climbing footage, equipment and techniques.

- The Eiger, 1974, by Dougal Haston, London: Cassell

- The 1982 book Eiger, Wall of Death by Arthur Roth is an historical account of first ascents of the north face.[24]

- The 1982 book Traverse of The Gods by Bob Langley is a World War II spy thriller where a group escaping from Nazi Germany is trapped and the only possible exit route is via the Nordwand.

- Eiger Dreams, a collection of essays by Jon Krakauer, begins with an account of Krakauer's own attempt to climb the north face.

- The IMAX film The Alps features John Harlin III's climb up the north face in September 2005. Harlin's father, John Harlin II, set out 40 years earlier to attempt a direct route (the direttissima) up the 6,000-foot (1,800 m) face, the so-called "John Harlin route". At 1300 m, his rope broke, and he fell to his death. Composer James Swearingen created a piece named Eiger: Journey to the Summit in his memory.

- The 2007 docu/drama film The Beckoning Silence featuring mountaineer Joe Simpson, recounting—with filmed reconstructions—the ill-fated 1936 expedition up the north face of the Eiger and how Heinrich Harrer's book The White Spider inspired him to take up climbing. The film followed Simpson's eponymous 2003 book. Those playing the parts of the original climbing team were Swiss mountain guides Roger Schäli (Toni Kurz), Simon Anthamatten (Andreas Hinterstoisser), Dres Abegglen (Willy Angerer) and Cyrille Berthod (Edi Rainer). The documentary won an Emmy Award the subsequent year.

- The 2008 German historical fiction film Nordwand is based on the 1936 attempt to climb the Eiger north face. The film is about the two German climbers, Toni Kurz and Andreas Hinterstoisser, involved in a competition with an Austrian duo to be the first to scale the north face of Eiger.

- The 2010 documentary Eiger: Wall of Death by Steve Robinson.

See also

References

- Retrieved from the Swisstopo topographic maps. The key col is the Nördliches Eigerjoch (3,605 m).

- Retrieved from Google Earth. The nearest point of higher elevation is northeast of the Mönch.

- Venables, Stephen (2014). "The Big Alpine Walls". First Ascent. London: Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1554074037.

The North Face of the Eiger is the biggest sheer face in Europe, over a mile high

- Reinhold Messner, The Big Walls: From the North Face of the Eiger to the South Face of Dhaulagiri, p. 41

- Venables, Stephen (2006-08-27). "The Eiger is my kind of therapy". London: The Sunday Times. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- Gillman, Peter and Leni (2016). Extreme Eiger: The Race to Climb the Eiger Direct. London: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781471134609.

The name first appeared as 'mons Egere' in a document in 1252 and is a contentious topic among philologists and etymologists. One argues that since the document was a land deed, the name was that of the farmer who first settled the meadows below the face, one Agiger or Aiger, which was later shaded into Eiger. Another proposes that Eiger is based on Latin and/or Greek words meaning sharp, pinnacle or peak. A third suggests that it derives from a German dialect phrase dr hej Ger - a ger being a sharp spear used in warfare. - Chapter 2, The Redoubtable Beufoys

- "3 - Suisse sud-ouest" (Map). Eiger Mönch Jungfrau (2014 ed.). 1:200 000. National Map 1:200'000. Wabern, Switzerland: Federal Office of Topography – swisstopo. ISBN 978-3-302-00003-9. Retrieved 2018-02-02 – via map.geo.admin.ch.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/11/travel/alps-glaciers-climate-change.html

- The Associated Press (2008-07-14). "Massive chunk falls from Swiss mountain". NBC News. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- From Strutt's Presidential Valedictory Address, 1938, in Alpine Journal, Vol. L, reprinted in Peaks, Passes and Glaciers, ed. Walt Unsworth, London: Allen Lane, 1981, p. 210

- 10 Hardest Mountains to Climb in the World

- Claire Eliane Engel, A History of Mountaineering in the Alps, 1950

- Daniel Anker and Rainer Rettner, Chronology of the Eiger from 1252 to 2013

- Gillman, Peter; Gillman, Leni (2016). "The Redoubtable Beaufoys". Extreme Eiger: The Race to Climb the Eiger Direct. Mountaineers Books. ISBN 9781680510515.

At 3.30 a.m. they set off up the Eiger's West Flank

- First Ascent of the Eiger's Mittellegi Ridge

- The north face of the Eiger mountainzone.com. Retrieved on 2010-03-04

- Alptraum der Alpen einestages.spiegel.de. Retrieved on 2010-03-04

- Alpinist Magazine. "Mark Wilford, Faces".

- "Acro-base.com video". Archived from the original on 2009-06-01. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- "Ski-Gliding the Eiger". YouTube.

- Michael Hopkin. "Eiger loses face in massive rockfall". BioEd Online. Archived from the original on 2009-04-06. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- https://www.merilibrary.com/The-Ice-Mirror/ItemId-ERD2013080039

- https://www.alpinejournal.org.uk/Contents/Contents_1980_files/AJ%201980%20121-129%20Pokorny%20Fiction.pdf

- Roth, Arthur (1982) "Eiger, wall of death". Norton. ISBN 0-393-01496-7 and (2000) Adventure Library. ISBN 1-885283-19-9.

Works cited

- Anker, Daniel (2000). Eiger: The Vertical Arena. Seattle: The Mountaineers.

- Harrer, Heinrich (1959). The White Spider: The History of the Eiger's North Face (in German) (3rd ed.). London.

- Pagel, David (1999). "My Dinner with Anderl". Ascent. Golden, Colorado: AAC Press: 13–26.

- Simpson, Joe (2002). The Beckoning Silence. London: Jonathan Cape Publishers. ISBN 0-09-942243-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eiger. |

- The Eiger on Summitpost

- "Eiger". Peakware.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. - photos

- The Eiger on Hikr

- The Eiger on Flickr

- Live webcam view of the Eiger north face

- New and Old Explorations of the Eiger, Photos & Video

- Ueli Steck wins inaugural Eiger Award 2008

- Are you still here? A bagman's view of climbing the Eigerwand, by Charles Sherwood.

- Obituary of Anderl Heckmair, The Independent, Feb. 3, 2005

- West face of Eiger