El Assaad Family

El-Assaad or Al As'ad (Arabic: الأسعد) is a feudal political family/clan originally from Najd and a main branch of the anza tribe.[1] Unrelated to Syrian or Palestinian Al-Assads, El-Assaad dynasty that ruled most of South Lebanon for three centuries and whose lineage defended fellow denizens of history’s Jabal Amel (Mount Amel) principality – today southern Lebanon – for 36 generations, throughout the Arab caliphate by Sheikh al Mashayekh (Chief of Chiefs) Nasif Al-Nassar ibn Al-Waeli,[2] Ottoman conquest under Shbib Pasha El Assaad,[3] Ali Bek El Assaad ruler of Belad Bechara (Part of Jabal Amel), Ali Nassrat Bek. Advisor of the Court and a Superior in the Ministry of Foreign affairs in the Ottoman Empire, Moustafa Nassar Bek El Assaad Supreme Court Judge of Lebanon and colonial French administration by Hassib Bek—also supreme court Judge and grand speaker at halls across the Levant. El-Assaads are considered now "Bakaweit" (title of nobility plural of "Bek" granted to a few wealthy families in Lebanon in the early eighteenth century), and previously considered Princes, however titles have changed over time.[4][5]

The patriarchy originated when the Najdi (Saudi) traveling Bedouin Ali Al Saghir (Saghir, the Young).They were proclaimed as El Assaad (the Most Rejoiceful) by their adopting people of Jabal Amel after liberating Sidon & Tyre, its ancient and Biblical capitals, from Byzantine tyrants (wherefrom the term originated). Ali's tribe, the Anazzah (of Bani Wael)also the tribe of Al-Saud royalty, travelled northwest in search of arable farmland.

During the El-Assaad era, they, as provincial governors by consent, were given Khuwwa (brotherly voluntary crop-sharing) by local clans to finance protecting their co-operative trade from outside occupation, peacefully upholding the autonomy of a laborious few in the midst of one massive imperial taxation hegemony after another. This continued until contemporary domestic ideological belligerence, foreign interferences, and emergence of corruption led to rapid depredation of the El-Assaads’ ability to maintain control.[6]

Background

Family background

The Shia feudal dynasty, which was established by Ali Al-Saghir in the 17th century after the execution of the Druze leader Fakhreddine II by the Ottoman leadership.[7] The El-Assaad-clan of the Ali Al-Saghir-family went on to dominate the area of Jabal Amel (modern-day Southern Lebanon) for almost three centuries,[8] with their base originally in Tayibe, Marjeyoun District.

When the 1858 Ottoman Land reforms led to the accumulated ownership of large tracts of land by a few families upon the expense of the peasants, the El-Assaad descendants of the rural Ali al-Saghir dynasty expanded their fief holdings as the provincial leaders in Jabal Amel.[9][10]

During the French colonial ruler over Greater Lebanon (1920-1943) the mandatory regime gave Shiite feudal families like El-Assaad

"a free hand in enlarging their personal fortunes and reinforcing their clannish powers."[11]

Ali Al-Saghir Dynasty

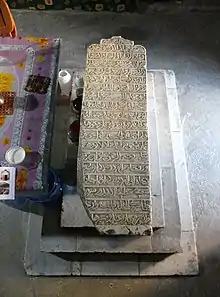

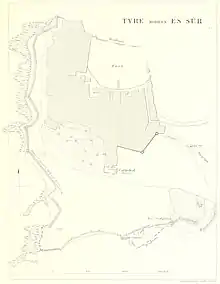

Ali al-Saghir – a leader of the discriminated Metwali, the Shia Muslims of what is now Lebanon – established a dynasty[12] that dominated the area of Jabal Amel for almost three centuries until the mid-twentieth century.[13] The scions of its El Assaad clan have continued to play a political role even into the 21st century, though of lately a rather peripheral one.[14] Around 1750, Jabal Amel's ruler from the Shiite dynasty of Ali al-Saghir (see above), Sheikh Nasif al-Nassar, initiated a number of construction projects to attract new inhabitants to the almost deserted town.[15] His representative in Tyre was the "tax-farmer and effective governor" Sheikh Kaplan Hasan. The main trade partners became French merchants, though both Hasan and Al-Nassar at times clashed with French authorities about the conditions of the commerce.[16]

.jpg.webp)

Amongst Al-Nassar's projects was a marketplace. While the former Maani palace was turned into a military garrison,[17] Al-Nassar commissioned the Serail at the Northern port as his own headquarters, which nowadays houses the police HQ. The military Al Mobarakee Tower from the Al-Nassar era is still well-preserved, too.

In 1752, construction of the Melkite cathedral of Saint Thomas was started thanks to donations from a rich merchant, George Mashakka – also spelled Jirjis Mishaqa[18] - in a place that had already housed a church during the Crusader period in the 12th century. The silk and tobacco trader had been persuaded by Al-Nassar to move from Sidon to Tyre. Numerous Greek Catholic families followed him there. Mashakka also contributed considerably to the construction of a great mosque, which is nowadays known as the Old Mosque.[19]

However, around the same time the resurgence of Tyre suffered some backlashes: the devastating Near East earthquakes of 1759 destroyed parts of the town and killed an unknown number of people as well. In 1781, Al-Nassar was killed in a power-struggle with the Ottoman governor of Sidon, Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar, who had the Shiite population decimated in brutal purges. Thus, the Shiite autonomy in Jabal Amel ended for a quarter century.

At the beginning of the 19th century though, another boom period set in: in 1810 a Caravanserai was constructed near the former palace of Emir Younes Maani and the marketplace area: Khan Rabu. A Khan was "traditionally a large rectangular courtyard with a central fountain, surrounded by covered galleries".[20] Khan Rabu (also transliterated Ribu) soon became an important commercial center. A few years later, the former Maani Palace and military garrison was transformed into a Caravanserai Khan as well.

In December 1831 Tyre fell under the rule of Mehmet Ali Pasha of Egypt, after an army led by his son Ibrahim Pasha had entered Jaffa and Haifa without resistance.[21] Two years later, Shiite forces under Hamad al-Mahmud from the Ali Al-Saghir dynasty (see above) rebelled against the occupation. They were supported by the British Empire and Austria-Hungary: Tyre was captured on 24 September 1839 after allied naval bombardments.[22] For their fight against the Egyptian invaders, Al-Mahmud and his successor Ali El-Assaad – a relative – were rewarded by the Ottoman rulers with the restoration of Shiite autonomy in Jabal Amel. However, in Tyre it was the Mamlouk family that gained a dominant position. Its head Jussuf Aga Ibn Mamluk was reportedly a son of the Anti-Shiite Jazzar Pasha (see above).

In 1865, Jabal Amel's ruler Ali El-Assaad died after a power struggle with his cousin Thamir al-Husain.

.jpg.webp)

The 1908 Young Turk Revolution and its call for elections to an Ottoman parliament triggered a power-struggle in Jabal Amel: on the one hand side Rida al-Sulh of a Sunni dynasty from Sidon, which had sidelined the Shia El-Assad clan of the Ali al-Saghir dynasty (see above) in the coastal region with support from leading Shiite families like the al-Khalil clan in Tyre. His opponent was Kamel El-Assaad from the Ali al-Saghir dynasty that still dominated the hinterland. The latter won that round of the power-struggle, but the political rivalry between al-Khalil and El Assaad would go on to be a main feature of Lebanese Shia politics for the next sixty years.

Ottoman Empire

The El-Assaad Family had a major role in Ottoman Empire's Beyrut, Tyre and Sidon. Leaders like Kamel El Assaad (Turkish: Kâmil El Esad Bey) Ali El Assaad (Father), Shbib Pasha El Assaad (son) and Ali Nassar El Assaad (grandson) were important political figures in Ottoman's Lebanon in the 1900s, Kamel El Assaad was Mebus (Turkish) and was a part of III. Meclis-i Mebusan and represented Beyrut. Ali Bek El Assaad was the Ruler of Bishara Shbib Pasha El Assaad had a role in the meetings organized in the Levant between (1877-1878), when the Russian army occupied (Adana) and headed towards Istanbul, which threatened the region with falling under a new foreign occupation, so the notables and dignitaries in the Levant met to consult on the matter of their future in When this danger occurred, Jabal Amel was represented by Shabib Pasha Al-Asaad.[23] Through these meetings, they demanded the independence of Syria in the event that the country was in danger of a foreign takeover, as they saw in Prince Abdul Qadir al-Jazaery as president of the country.Ali Nassar Bek El Assaad was an inspector by the Ottoman Empire over the states of Aleppo and the Levant . During the French mandate, he became Minister of Agriculture and Supply in the government of Charles Al-Dabbas in 1926.

Post Ottoman Empire

After the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman rule started in 1916 and the Sharifian Army conquered the Levant in 1918 with support from the British Empire, the Jamal Amil feudal leader Kamel El Assaad of the Ali Al-Saghir dynasty, who had been an Ottomanist before, declared the area – including Tyre – part of the Arab Kingdom of Syria on 5 October 1918. However, the pro-Damascus regime in Beirut appointed Riad al-Sulh as governor of Sidon who in turn appointed Abdullah Yahya al-Khalil in Tyre as the representative of Faisal I.[24][25]

While the feudal lords of the As'ad / Ali al-Saghir and Sulh dynasties competed for power,[26] [27] their support for the Arab Kingdom put them immediately into conflict with the interests of the French colonial empire: on 23 October 1918, the joint British and French military regime of the Occupied Enemy Territory Administration was declared, with Jabal Amel falling under French control.[13]

Subsequently, the French Army used the historical garrison building of Khan Sour as a base, which had apparently been taken over as property by the Melkite Greek Catholic Archeparchy of Tyre from the Franciscan Fathers.In reaction, a guerrilla group started military attacks on French troops and pro-French elements in Tyre and the neighbouring areas, led by Sadiq al-Hamza from the Ali al-Saghir clan.[13]

In contrast, the most prominent organiser of nonviolent resistance against the French ambitions in Jabil Amel became the Shi'a Twelver Islamic scholar Sayyid Abdel Hussein Sharafeddine (born 1872), the Imam of Tyre.[8] He had played a decisive role in the 1908 power struggle between the El Assaad clan of the Ali Al-Saghir dynasty on the one hand side and the al-Sulh dynasty with their Tyrian allies of the al-Khalil family (see above) in favor of the former. His alliance with El Assad strengthened after WWI, as

"He achieved his prominent position in the community through his reputation as a widely respected 'alim [religious scholar] whose books were taught in prominent Shi'ite schools such as Najaf in Iraq and Qum in Iran."

On the first of September 1920, the French colonial rulers proclaimed the new State of Greater Lebanon under the guardianship of the League of Nations represented by France. The French High Commissioner in Syria and Lebanon became General Henri Gouraud. Tyre and the Jabal Amel were attached as the Southern part of the Mandate.[28]

Still in 1920, the first municipality of Tyre was founded, which was headed by Ismail Yehia Khalil from the Shia feudal dynasty of al-Khalil. The al-Khalil family had traditionally been allies of the al-Sulh clan, whereas Imam Sharafeddin supported the rival al-Asa'ad clan of the Ali al-Saghir dynasty since 1908 .

In 1922, Kamel El-Assaad[29] returned from exile and started an uprising against the French occupation, but was quickly suppressed and died in 1924.[13]

Sadr managed to gradually break up the inherited power of Kamel El Assaad – a close ally of President Suleiman Frangieh – from the Ali Al-Saghir dynasty after almost three centuries, although El Assaad's list still dominated the South in the parliamentary elections of 1972 and the by-elections of 1974.[13][11]

In the 1992 elections, Kamel El Assaad from the feudal dynasty of Ali Al-Saghir headed a list that lost against Amal. Nasir al-Khalil, the son of Tyre's former longtime deputy Kazim al-Khalil who died in 1990, was not elected either and failed again in 1996.[25]

Ahmed El-Assaad

When President Camille Chamoun introduced a new electoral system in 1957, El Assaad for the first time lost the vote for deputy.[30] He had presented his candidacy in Tyre, the stronghold of his Shia rival Kazem al-Khalil, rather than in his traditional home constituency of Bint-Jbeil.[31]

1958 Lebanese Civil War

As a consequence, al-Asaad became a "major instigator of events against Chamoun" and his allies, primarily al-Khalil, who likewise was a long-time member of parliament and the scion of a family of large landowners ("zu'ama")[32] ruling through patronage systems:[33]

"The Khalils, with their age-old ways, [..] were known for being particularly rough and hard."[34]

During the 1958 crisis, Kazem al-Khalil was the only Shi'ite minister in the cabinet of Sami as-Sulh, to whose family the al-Khalil feudal dynasty was traditionally allied. Thus,

"Kazim's followers had a free hand in Tyre; they could carry Guns on the streets".

Then, after the formation of the United Arab Republic (UAR) under Gamal Abdel Nasser in February 1958, tensions escalated in Tyre between the forces of Chamoun and supporters of Pan-Arabism. Demonstrations took place – as in Beirut and other cities – that promoted pro-union slogans and protested against US foreign policy.[35] A US-Diplomat, who travelled to Southern Lebanon shortly afterwards, reported though that the clashes were more related to the personal feud between El Assaad and Al-Khalil than to national politics.

Still in February, five of its students were arrested and "sent to jail for trampling on the Lebanese flag and replacing it with that of the UAR."[36] On 28 March, soldiers and followers of Kazem al-Khalil opened fire on demonstrators and – according to some reports – killed three. On the second of April, four[37] or five protestors were killed and about a dozen injured.[35]

In May, the insurgents in Tyre gained the upper hand.[38] Ahmad El Assaad and his son Kamel al-Asaad supported them, also with weapons.[39] According to a general delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) who visited in late July, "heavy fighting went on for 16 days".[40] Kazem al-Khalil was expelled from the city and al-Asaad' allies took over control of the city. The crisis eventually dissolved in September, when Chamoun stepped down. Al-Khalil returned still in 1958, but was attacked several times by gunmen.[41]

Despite the victory of the El Assaad dynasty, its power soon began to crumble.

Kamel El Assaad

Kamel El Assaad served starting early 1960 as Deputy (Member of the Lebanese Parliament) of Bint Jbeil, succeeding his father late Ahmed Asaad and then held the parliamentary seat of Hasbaya-Marjayoun from 1964 and 1992. He was elected Speaker of the Lebanese Parliament several times, May to October 1964, May to October 1968, with his final stint from 1970 to 1984.[27] Assaad chaired the parliamentary sessions, which saw the election of presidents Elias Sarkis, Bachir Gemayel, and Amine Gemayel.

Assaad left politics in 1984 after Syria's intervention in Lebanon's internal political policies related to the ratification of the Agreement of May 17, 1984, between Israel and Lebanon, and the period of political crisis which followed.[42]

He was the founder and president of the Lebanese Social Democratic Party (Arabic: الحزب الديمقراطي الاشتراكي). He also had ministerial positions in two Lebanese governments serving as Minister of Education and Fine Arts from October 1961 to February 1964, and as Minister of Health and Minister of Water and Electricity Resources from April to December 1966.

After serving as a Member of Parliament and its Speaker several times, Assaad later ran for public office but failed to get elected in the Lebanese elections in 1992, 1996 and 2000, in the face of pro-Syrian and pro-Iranian political groups Amal and Hezbollah lists, and called for a boycott of the elections in 2005. He died in 2010, at the age of 78.[43]

Lebanese Option Party

Lebanese Option Party حزب الإنتماء اللبناني | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Ahmad Kamel El-Assaad |

| Founded | 2007 (Movement) 2010 (Party) |

| Headquarters | Beirut, Lebanon |

| Ideology | Secularism Moderate Shia Islamism Liberalism Economic liberalism |

| Political position | Centre-right/Centre |

| National affiliation | March 14 Alliance |

| Website | |

| www.lebaneseoption.org | |

Lebanese Option Party (LOP) (Arabic: حزب الإنتماء اللبناني, in English Lebanese Option, French L'Option libanaise) is a Lebanese secular and an economically liberal party, which is also a predominantly Shia political movement established in 2007.[44] It is headed by Ahmad Kamel El-Assaad (Arabic: أحمد كامل الأسعد), the son of the former speaker of the Lebanese Parliament Kamel El-Assaad and the grandson of the former speaker of the Parliament Ahmad El-Assaad (Arabic: أحمد بك الأسعد).

Lebanese Option strongly protests the political hegemony of the two movements Hezbollah and Amal Movement on the Shi'ite community in Lebanon.[45] Its platform is more in line with the Lebanese majority March 14 Alliance and greatly opposed to mainstream Shi'ite movements allied with the March 8 Alliance, namely Hezbollah and Amal Movement. But the Lebanese Option is not an official part of the March 14 Alliance and keeps an independent secular status.[46]

Democratic Socialist Party

The Democratic Socialist Party is a Lebanese party founded and led by former Lebanese speaker of parliament Kamel Al-Assad.

The party is hostile to Hezbollah and Amal movement, and enjoys most of its support from the Lebanese Shi'a community.

Legacies

- El Assaads owned most of South Lebanon, and almost all lands bordering Palestine and Lebanon.[47]

- One of the Largest Armies in Lebanon between 1700-early 1900's were the El Assaad clan's army.

- The most influential Shia Leader in the 1700s was Nasif Al-Nassar.

- The largest dye trade in Lebanon in the Renaissance period was run by the El Assaads.

- Tebnin Castle, Maroun Castle and Doubiyeh Castle were owned by the El Assaads.

- El Assaads once ruled Tyre, Jabal Amel, Mount Hunin (Owned), Qana (Owned), Tebnin, taybe, Al-Shafiq, Al-Sa'abia, Nabatiyeh, Chamaa, Jbaa and Aabbassiyeh which was named after Abbas Al Nassar[48]

Family and tribal ties

- Al Tamer Family - direct branch (Lebanon)

- Al Salman Family - direct branch (Lebanon)

- Al Waeli Family - originated branch (Saudi Arabia)

- Al Enezi tribe - originated branch (Middle East)

- Al Qahtani clan - originated branch (Saudi Arabia)

- Al Amili Family - distant branch

- Al Shukr Family - ancestry branch

- Al Salmi Family - ancestry branch

- Bakr Bin Wael Tribe - original tribe

Notable individuals

- Nasif Al Nassar - most powerful Shia sheikh in Lebanon in the 18th century.

- Ali Al Saghir - a powerful leader of Jabal Amel.

- Prince Muhammad Al-Mahmoud - ruler of Jabal Amel.

- Prince Muhammad bin Hazaa Al-Waeli - ruler of Jabal Amel.

- Prince Hussain Al-Salman - ruler of Jabal Amel, inherited Mount Hunin and Qana.

- Prince Nassar Al-Ahmad - ruler of Jabal Amel.

- Prince Abbas Al-Muhammad - ruler of Tyre, owner of Maroun Castle, Al-Abbasiya town was named after him.

- Prince Salman bin Salman - ruler of Tyre, Jabal Amel.

- Prince Hussain Al Salman - ruler of Jabal Amel, inherited Mount Hunin and Qana.

- Prince Thamer Al Salman - ruler of Jabal Amel, Tyre, Mount tibnin, Mount Hunin, Qana, Nabatiyeh, Jabaa.

- Hamad Bek El Assaad - ruler of Jabal Amel, poet.

- Ali Mahmoud Bek El Assaad - ruler of Jabal Amel.

- Khalil Bek El Assaad - appointed Ottoman Governor of Nablus, Al Balqa, Marjayoun, Tyre and Homs.

- Zeinab Ali Bek El Assaad - poet and writer.

- Fatima Assaad Khalil Nasif Al Nassar - poet and writer.

- Shbib Pasha El Assaad - minister of the Ottoman Empire, army leader.

- Ali Nasrat El Assaad - advisor of the Court and a Superior in the Ministry of Foreign affairs in the Ottoman Empire.

- Kamil Bey (Esad) El-Assaad - representative of the Ottoman Empire in Beyrut.[49][50]

- Ahmed El Assaad - 3rd Legislative Speaker of Lebanon.

- Hikmet El Assaad - classmate of Abulhamid II, also was poisoned by Abdulhamid II for what was said to be 'excessive pride'.

- Nezih El Assaad - head of the El Assaad Family after his father Shbib Pasha's passing, Leader of the clan.

- Kamel Bek El Assaad- 5th Legislative Speaker of Lebanon, Minister of Education, Minister of Water and Electricity, founder of Democratic Socialist Party (Lebanon).

- Moustafa Nassar Bek El Assaad - Supreme Court judge.

- Ahmad Kamel El Assaad - Lebanese Option Party founder, political candidate.

- Nael El Assaad - envoy for HM King Abdullah of Jordan and former husband of late Saudi magnate Adnan Khashoggi’s sister Soheir.

- Said El Assaad - former Lebanese Ambassador of Switzerland, France and Belgium and a former Member of Parliament.

- Bahija Al Solh El Assaad - wife of Said El Assaad, daughter of Prime Minister Riad Al Solh, aunt of Waleed Bin Talal.

- Nasrat El Assaad - ambassador of Lebanon to numerous countries.

- Riad El Assaad - businessperson, financier of the Together Towards Change syndicate of independents, political candidate, First cousin to Waleed Bin Talal.

- Maan El Assaad - human rights lawyer and propagator of the Tayyar El Assaadi.

- Haidar El Assaad - historian and among the first official delegates to visit the new People’s Republic of China in the 1960s following Ministerial civil service – later serving as a director at the FAO of the United Nations and consultant to TRW and the World Bank.

- Assaad El Assaad - Lebanese ambassador.

- Mohammed Nasrat El Assaad - Lebanese ambassador.

- Hani El Assaad - President of SITA

See also

- 1968 Lebanese general election in Marjeyoun-Hasbaya

- Kamel El Assaad

- List of legislative speakers of Lebanon

- Ahmed El Assaad

- Tebnine

- Belad Bechara

- Jabal Amel

- Chamaa

- Tyre, Lebanon

- Democratic Socialist Party (Lebanon)

- Lebanese Option Party

- Lebanese Shia Muslims

- Shia Dynasties

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Lebanon |

|

|

References

- Fouad Ajami, The Vanished Imam: Musa al-Sadr and the Shi'a of Lebanon (Itahac: Cornell University Press, 1986) p. 69

- Philipp, Thomas (2013). Acre: The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian City, 1730–1831. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231506038.

- M. Firro, Kais (2006). "The Shi'is in Lebanon: Between Communal 'Asabiyya and Arab Nationalism, 1908-21". .Middle Eastern Studies. 42 (4): 535–550. doi:10.1080/00263200600642175. JSTOR 4284474. S2CID 144197971.

- Gharbieh, Hussein M (1996). "bPolitical awareness of the Shi'ites in Lebanon : the role of Sayyid #Abd al-Husain Sharaf al-Din and Sayyid Musa al-Sadr". Durham Theses, Durham University (1): 3–293.

- Nucho, Emile N. (1972). "The Shi'i Matawila of Lebanon: A Study of their Political Development in Historical Perspective". McGill University. Institute of Islamic Studies (1): 15,134.

- Grimblat, Francis (1988). "LA Communauté Chiite Libanaise et Le Mouvement National Palestinien 1967–1986". Guerres Mondiales et Conflits Contemporains. 151 (151): 71–91. JSTOR 25730511.

- Winter, Stefan (2010). The Shiites of Lebanon under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1788. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 126, 129–134, 140, 177–178. ISBN 9780521765848.

- Gharbieh, Hussein M. (1996). Political awareness of the Shi'ites in Lebanon: the role of Sayyid 'Abd al-Husain Sharaf al-Din and Sayyid Musa al-Sadr (PDF) (Doctoral). Durham: Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, University of Durham. pp. 121, 127.

- Abisaab, Rula Jurdi; Abisaab, Malek (2017). The Shi'ites of Lebanon: Modernism, Communism, and Hizbullah's Islamists. New York: Syracuse University Press. pp. 9–11, 16–17, 24, 107. ISBN 9780815635093.

- http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1521/1/1521.pdf?EThOS%20(BL) |page= 43,44,45,46|

- Firro, Kais (2002). Inventing Lebanon: Nationalism and the State Under the Mandate. London and New York: I. B. Tauris. pp. 159, 166. ISBN 978-1860648571.

- Winter, Stefan (2010). The Shiites of Lebanon under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1788. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 126, 129–134, 140, 177–178. ISBN 9780521765848.

- Gharbieh, Hussein M. (1996). Political awareness of the Shi'ites in Lebanon: the role of Sayyid 'Abd al-Husain Sharaf al-Din and Sayyid Musa al-Sadr (PDF) (Doctoral). Durham: Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, University of Durham.

- Chalabi, Tamara (2006). The Shi'is of Jabal 'Amil and the New Lebanon: Community and Nation-State. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403982940.

- Badawi, Ali Khalil (2018). "TYRE". Al-Athar Magazine. 4th: 46–49.

- Winter, Stefan (2010). The Shiites of Lebanon under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1788. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 126, 129–134, 140, 177–178. ISBN 9780521765848

- Jaber, Kamel (2005). Memory of the South. Beirut: South for Construction. pp. 94, 96–97.

- Jidejian, Nina (2018). TYRE Through The Ages (3rd ed.). Beirut: Librairie Orientale. pp. 272–277. ISBN 9789953171050.

- Sajdi, Dana (2013). "The Barber of Damascus: Nouveau Literacy in the Eighteenth-Century Ottoman Levant". Stanford University Press. 1 (1): 77–114. JSTOR j.ctvqsf20g.

- "The Souks and Khan el Franj". Al Mashriq (the Levant). Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- Aksan, Virginia (2014). Ottoman Wars, 1700–1870: An Empire Besieged. New York: Routledge. pp. 370–371. ISBN 9780582308077.

- Farah, Caesar E. (2000). Politics of Interventionism in Ottoman Lebanon, 1830–61. Oxford / London: I.B.Tauris / Centre for Lebanese Studies. p. 42. ISBN 978-1860640568.

- Winter, Stefan (2010). The Shiites of Lebanon under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1788. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 126, 129–134, 140, 177–178. ISBN 9780521765848.

- Chalabi, Tamara (2006). The Shi'is of Jabal 'Amil and the New Lebanon: Community and Nation-State, 1918–1943. New York: Springer. pp. 25, 62–63. ISBN 9781349531943.

- Shanahan, Rodger (2005). The Shi'a of Lebanon – The Shi'a of Lebanon Clans, Parties and Clerics (pdf). London and New York: Tauris Academic Studies. pp. 16, 41–42, 46–48, 80–81, 104. ISBN 9781850437666.

- Shanahan, Rodger (2005). The Shiʻa of Lebanon: clans, parties and clerics. I.B.Tauris. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-85043-766-6.

- (in Arabic)Republic of Lebanon - House of Representatives History

- Hamzeh, Ahmad Nizar (2004). In the Path of Hizbullah. New York: Syracuse University Press. pp. 11, 82, 130, 133. ISBN 978-0815630531.

- "La Situation Poltique Au Liban". Studia Diplomatica. 33 (1/2): 91–98. 1980. JSTOR 44834490.

- http://www.cedarsrevolution.net/jtphp/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=857&Itemid=30

- Nir, Omri (November 2004). "The Shi'ites during the 1958 Lebanese Crisis". Middle Eastern Studies. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. 40 (6): 109–129. doi:10.1080/0026320042000282900. JSTOR 4289955. S2CID 145378237 – via JSTOR.

- Habachy, Saba (1964). "The Republican Institutions of Lebanon: Its Constitution". The American Journal of Comparative Law. 13 (4): 594–604. doi:10.2307/838431. JSTOR 838431.

- Shaery-Eisenlohr, Roschanack (2011). Shiite Lebanon: Transnational Religion and the Making of National Identities. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0231144278.

- Ajami, Fouad (1986). The Vanished Imam: Musa al Sadr and the Shia of Lebanon. London: I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd. pp. 42–45, 85–86. ISBN 9781850430254.

- Attié, Caroline (2004). Struggle in the Levant: Lebanon in the 1950s. London - New York: I.B.Tauris. pp. 155, 158, 162–163. ISBN 978-1860644672.

- Sorby, Karol (2000). "Lebanon: The Crisis of 1958" (PDF). Asian and African Studies. 9: 88, 91 – via Slovenská Akadémika Vied.

- Qubain, Fahim Issa (1961). Crisis in Lebanon. Washington D.C.: The Middle East Institute. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-1258255831.

- Cobban, Helena (1985). The making of modern Lebanon. Boulder: Westview Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0813303079.

- "July - July 1958 : US Marines in Beirut". monthlymagazine.com. July 5, 2013. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- Bugnion, François; Perret, Françoise (2018). From Budapest to Saigon, 1956-1965 - History of the International Committee of the Red Cross (PDF). Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross. p. 372. ISBN 978-2-940396-70-2.

- Blanford, Nicholas (2011). Warriors of God: Inside Hezbollah's Thirty-Year Struggle Against Israel. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 9780679605164.

- "aoun les negociations avec israel doivent se limiter a laspect technique".

- "Former Speaker Kamel El Assaad dies at age 78".

- Lebanese Shiite Political Party Statement on Hezbollah (from The Daily Star

- YaLibnan article: Ahmad El-Assaad: An alternative to Hezbollah in Lebanon Archived 2009-11-27 at the Wayback Machine

- El Husseini, Rola (2015). "Cracks in the Hezbollah monopoly". Washington Post (1). Washington Post.

- https://dra.american.edu/islandora/object/0910capstones%3A157/datastream/PDF/view |pages 12,13 |

- Yovitchitch, Cyril (2016). "Between Antiquity and Modernity: The Castle of Doubiyeh in South Lebanon". Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies. 4 (1): 98–119. doi:10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.4.1.0098. S2CID 164101345.

- (In Turkish)https://www.tbmm.gov.tr/tutanaklar/TUTANAK/MECMEB/mmbd03icf01c001/mmbd03icf01c001ink002.pdf

- (In Turkish)https://www.tbmm.gov.tr/tutanaklar/TUTANAK/MECMEB/mmbd02ic01c002/mmbd02ic01c002ink033.pdf