Caravanserai

A caravanserai (or caravansary; /kærəˈvænsəˌraɪ/)[1] was a roadside inn where travelers (caravaners) could rest and recover from the day's journey.[2] Caravanserais supported the flow of commerce, information and people across the network of trade routes covering Asia, North Africa and Southeast Europe, most notably the Silk Road.[3][4] Although many were located along rural roads in the countryside, urban versions of caravanserais were also historically common in cities throughout the Islamic world, though they were often called by other names such as khan, wikala, or funduq.[5]

Terms and etymology

Caravanserai

The word کاروانسرای kārvānsarāy is a Persian compound word combining kārvān "caravan" with sarāy "palace", "building with enclosed courts".[6][3] Here "caravan" means a group of traders, pilgrims or other travellers, engaged in long-distance travel. The word is also rendered as caravansary, caravansaray, caravanseray, caravansara, and caravansarai.[4] In scholarly sources, it is often used as an umbrella term for multiple related types of commercial buildings similar to inns or hostels, whereas the actual instances of such buildings had a variety of names depending on the region and the local language.[5] However, the term was typically preferred for rural inns built along roads outside of city walls.[7]

The word serai is sometimes used with the implication of caravanserai. A number of place-names based on the word sarai have grown up: Mughal Serai, Sarai Alamgir and the Delhi Sarai Rohilla railway station for example, and a great many other places are also based on the original meaning of "palace".

Khan

The word khan (خان) derives from Middle Persian hʾn' (xān, “house”).[8][5] It typically referred to an "urban caravanserai" built within a town or a city.[5][9] In Turkish the word is rendered as han.[5] The same word was used in Bosnian, having arrived through Ottoman conquest. In addition to Turkish and Persian, the term was widely used in Arabic as well, and examples of such buildings are found throughout the Middle East from as early as the Ummayyad period.[5][9]

Funduq

The term funduq (Arabic: فندق; sometimes spelled foundouk or fondouk from the French transliteration) is frequently used for historic inns in Morocco and around western North Africa.[5] The word comes from Greek pandocheion, lit.: "welcoming all",[10][5] thus meaning 'inn', led to funduq in Arabic (فندق), pundak in Hebrew (פונדק), fundaco in Venice, fondaco in Genoa and alhóndiga[11] or fonda in Spanish (funduq is the origin of Spanish term fonda). In the cities of this region such buildings were also frequently used as housing for artisan workshops.[12][13][14]:318

Wikala

The Arabic word wikala (وكالة), sometimes spelled wakala or wekala, is a term found frequently in historic Cairo for an urban caravanserai which housed merchants and their goods and served as a center for trade, storage, transactions and other commercial activity.[15] The word wikala means roughly "agency" in Arabic, in this case a commercial agency,[15] which may also have been a reference to the customs offices that could be located here to deal with imported goods.[16] The term khan was also frequently used for this type of building in Egypt.[5]

History

Caravanserais were a common feature not only along the Silk Road, but also along the Achaemenid Empire's Royal Road, a 2,500-kilometre-long (1,600 mi) ancient highway that stretched from Sardis to Susa according to Herodotus: "Now the true account of the road in question is the following: Royal stations exist along its whole length, and excellent caravanserais; and throughout, it traverses an inhabited tract, and is free from danger."[17] Other significant urban caravanserais were built along the Grand Trunk Road in the Indian subcontinent, especially in the region of Mughal Delhi and Bengal Subah.

Throughout most of the Islamic period (7th century and after), caravanserais were a common type of structure both in the rural countryside and in dense urban centers across the Middle East, North Africa, and Ottoman Europe.[5] A number of 12th to 13th-century caravanserais or hans were built throughout the Seljuk Empire, many examples of which have survived across Turkey today[18][19] (e.g. the large Sultan Han in Aksaray Province) as well as in Iran (e.g. the Ribat-i Sharaf in Khorasan). Urban versions of caravanserais also became important centers of economic activity in cities across these different regions of the Muslim world, often concentrated near the main souq areas, with many examples still standing in the historic areas of Damascus, Aleppo, Cairo, Istanbul, Fes, etc.[20][21][22][23][14]

In many parts of the Muslim world, caravanserais also provided revenues that were used to fund charitable or religious functions or buildings. These revenues and functions were managed through a waqf, a protected agreement which gave certain buildings and revenues the status of mortmain endowments guaranteed under Islamic law.[24][25][26] Many major religious complexes in the Ottoman and Mamluk empires, for example, either included a caravanserai building (like in the külliye of the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul) or drew revenues from one in the area (such as the Wikala al-Ghuri in Cairo, which was built to contribute revenues for the nearby complex of Sultan al-Ghuri).[23][27][28]

Caravanserai in Arab literature

Al-Muqaddasi the Arab geographer wrote in 985 CE about the hostelries, or wayfarers' inns, in the Province of Palestine, a province at that time listed under the topography of Syria, saying: "Taxes are not heavy in Syria, with the exception of those levied on the Caravanserais (Fanduk); Here, however, the duties are oppressive..."[29] The reference here being to the imposts and duties charged by government officials on the importation of goods and merchandise, the importers of which and their beasts of burden usually stopping to take rest in these places. Guards were stationed at every gate to ensure that taxes for these goods be paid in full, while the revenues therefrom accruing to the Fatimid kingdom of Egypt.

Architecture

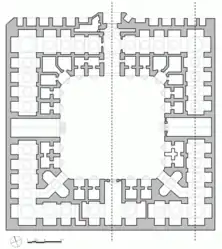

Most typically a caravanserai was a building with a square or rectangular walled exterior, with a single portal wide enough to permit large or heavily laden beasts such as camels to enter. The courtyard was almost always open to the sky, and the inside walls of the enclosure were outfitted with a number of identical animal stalls, bays, niches or chambers to accommodate merchants and their servants, animals, and merchandise.[30]

Caravanserais provided water for human and animal consumption, washing and ritual purification such as wudu and ghusl. Sometimes they had elaborate public baths (hammams), or other attached amenities such as a fountain or a sabil/sebil. They also kept fodder for animals and had shops for travellers where they could acquire new supplies. In addition, some shops bought goods from the travelling merchants.[31] Many caravanserais were also equipped with small mosques, such as the elevated examples in the Seljuk and Ottoman caravanserais in Turkey.[23][32][22]

In Cairo, starting in the Burji Mamluk period, wikalas (urban caravanserais) were frequently several stories tall and often included a rab', a low-income rental apartment complex, which was situated on the upper floors while the merchant accommodations occupied the lower floors.[33][21] In addition to making the best use of limited space in a crowded city, this also provided the building with two sources of revenue which were managed through the waqf system.[25][34]

Notable caravanserais

- Ağzıkara Han, Ağzıkarahan (Aksaray Province), Turkey

- Akbari Sarai, Lahore, Pakistan

- Büyük Han, Nicosia, Cyprus

- Büyük Valide Han, Istanbul, Turkey

- Büyük Yeni Han, Istanbul, Turkey

- Caravanserai of Sa'd al-Saltaneh, Qazvin, Iran

- Corral del Carbón, Granada, Spain

- Funduq Nejjarine, Fes, Morocco

- Funduq Sagha, Fes, Morocco

- Funduq Shamma'in, Fes, Morocco

- Funduq Staouniyyin, Fes, Morocco

- Garghabazar Caravanserai, Kharabakh, Azerbaijan

- Khan al-Tujjar, Nablus, West Bank

- Khan al-Tujjar (Mount Tabor)

- Khan al-Umdan, Acre, Israel

- Khan As'ad Pasha, Damascus, Syria

- Khan Jaqmaq, Damascus, Syria

- Khan el-Khalili, Cairo, Egypt

- Khan Sulayman Pasha, Damascus, Syria

- Khan Tuman, Damascus, Syria

- Koza Han, Bursa, Turkey

- Kürkçü Han, Istanbul, Turkey

- Manuc's Inn, Bucharest, Romania

- Multani Caravanserai, Baku, Azerbaijan

- Rabati Malik, Uzbekistan

- Sultan Han, Sultanhanı (Aksaray Province), Turkey

- Sultan Han, Sultanhanı (Kayseri Province), Turkey

- Orbelian's Caravanserai, Armenia

- Nampally Sarai, Nampally, Hyderabad, India

- Shaki Caravanserai, Shaki, Azerbaijan

- Wikala al-Ghuri, Cairo, Egypt

- Wikala Qaytbay (at Bab al-Nasr), Cairo, Egypt

- Wikala Qaytbay (at al-Azhar), Cairo, Egypt

- Zeinodin Caravanserai, Zein-o-din, Yazd, Iran

Gallery

1850 drawing of Khan al-Tujjar, near Mount Tabor, Israel

1850 drawing of Khan al-Tujjar, near Mount Tabor, Israel

Khan al-Wazir, Aleppo, Syria

Khan al-Wazir, Aleppo, Syria Inside the Orbelian's Caravanserai, Armenia

Inside the Orbelian's Caravanserai, Armenia

Caravanserai of Shah Abbas, now Abbasi Hotel, in Isfahan, Iran. View is from the courtyard (sahn).

Caravanserai of Shah Abbas, now Abbasi Hotel, in Isfahan, Iran. View is from the courtyard (sahn). Abandoned caravanserai in Neyestānak, Iran

Abandoned caravanserai in Neyestānak, Iran

1823 etching of Bara Katra, or Great Caravanserai, in Dhaka, Bangladesh; built by the Mughal Prince Shah Shuja

1823 etching of Bara Katra, or Great Caravanserai, in Dhaka, Bangladesh; built by the Mughal Prince Shah Shuja.jpg.webp) 1817 sketch of the Choto Katra caravanserai in Dhaka, Bangladesh; built by the Mughal viceroy Shaista Khan

1817 sketch of the Choto Katra caravanserai in Dhaka, Bangladesh; built by the Mughal viceroy Shaista Khan.jpg.webp) Anderkilla in Chittagong, Bangladesh

Anderkilla in Chittagong, Bangladesh

See also

- Architecture of Azerbaijan

- Bedesten

- Caravan city

- Islamic architecture

- List of caravanserais

- List of caravanserais in Azerbaijan

- List of Seljuk hans and kervansarays in Turkey

- List of streets, hans and gates in Grand Bazaar, Istanbul

- Motel

- Persian architecture

- Rest area

- Roadhouse

- Turkish architecture

References

- "Dictionary.com – caravansary". Retrieved 31 Jan 2016.)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Caravanserais: cross-roads of commerce and culture along the Silk Roads | Silk Roads Programme". en.unesco.org. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- Society, National Geographic (2019-07-23). "Caravanserai". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Caravanserai". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press.

- "caravanserai | Origin and meaning of caravanserai by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- "Caravansary | building". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- MacKenzie, D. N. (1971), “xān”, in A concise Pahlavi dictionary, London, New York, Toronto: Oxford University Press, p. 93.

- "Khan | architecture". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- "Strong's Greek: 3829. πανδοχεῖον (pandocheion) -- an inn". biblehub.com.

- "alhóndiga in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española".

- Parker, Richard (1981). A practical guide to Islamic Monuments in Morocco. Charlottesville, VA: The Baraka Press.

- Touri, Abdelaziz; Benaboud, Mhammad; Boujibar El-Khatib, Naïma; Lakhdar, Kamal; Mezzine, Mohamed (2010). Le Maroc andalou : à la découverte d'un art de vivre (2 ed.). Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Royaume du Maroc & Museum With No Frontiers. ISBN 978-3902782311.

- Le Tourneau, Roger (1949). Fès avant le protectorat: étude économique et sociale d'une ville de l'occident musulman. Casablanca: Société Marocaine de Librairie et d'Édition.

- Hathaway, Jane (2008). The Arab Lands under Ottoman Rule: 1516-1800. Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 9780582418998.

- AlSayyad, Nezar (2011). Cairo: Histories of a City. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 143. ISBN 978-0-674-04786-0.

- "The History - Herodotus" - http://classics.mit.edu/Herodotus/history.mb.txt

- "Seljuk Caravanserais". Archnet. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Seljuk Caravanserais on the route from Denizli to Dogubeyazit". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- "Khans of Damascus". Archnet. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- Williams, Caroline (2018). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide (7th ed.). Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

- Kuban, Doğan (2010). Ottoman Architecture. Antique Collectors' Club.

- Sumner-Boyd, Hilary; Freely, John (2010). Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (Revised ed.). Tauris Parke Paperbacks.

- "Waḳf". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill. 2012.

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. 2007. Cairo of the Mamluks: A History of Architecture and its Culture. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

- Çelik, Jennifer (2015-06-09). "Waqf: The backbone of Ottoman beneficence". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- Kuban, Doğan (2010). Ottoman Architecture. Antique Collectors' Club.

- "Wakala Qansuh al-Ghawri". ArchNet. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- Mukaddasi, Description of Syria, Including Palestine, ed. Guy Le Strange, London 1886, pp. 91, 37

- Sims, Eleanor. 1978. Trade and Travel: Markets and Caravansary.' In: Michell, George. (ed.). 1978. Architecture of the Islamic World - Its History and Social Meaning. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 101.

- Ciolek, T. Matthew. 2004-present. Catalogue of Georeferenced Caravansaras/Khans Archived 2005-02-07 at the Wayback Machine. Old World Trade Routes (OWTRAD) Project. Canberra: www.ciolek.com - Asia Pacific Research Online.

- Freely, John (2008). Storm on Horseback: The Seljuk Warriors of Turkey. I. B. Tauris.

- Yeomans, Richard (2006). The Art and Architecture of Islamic Cairo. Reading: Garnet. pp. 230-231. ISBN 978-1-85964-154-5.

- Denoix, Sylvie; Depaule, Jean-Charles; Tuchscherer, Michel, eds. (1999). Le Khan al-Khalili et ses environs: Un centre commercial et artisanal au Caire du XIIIe au XXe siècle. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Vladimir Braginskiy. Tourist Attractions in the USSR: A Guide. Raduga Publishers, 1982. 254 pages. Page 104.

The whole of the centre of Sheki has been proclaimed a reserve protected by the state. To take you back to the time of the caravans, two large eighteenth-century caravanserais have been preserved with spacious courtyards where the camels used to rest, cellars where goods were stored, and rooms for travellers.

Further reading

- Branning, Katharine. 2018. turkishhan.org, The Seljuk Han in Anatolia. New York, USA.

- Cytryn-Silverman, Katia. 2010. The Road Inns (Khans) in Bilad al-Sham. BAR (British Archaeological Reports), Oxford. ISBN 9781407306711

- Kīānī, Moḥammad-Yūsuf; Kleiss, Wolfram (1990). "Caravansary". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 7. pp. 798–802.

- Erdmann, Kurt, Erdmann, Hanna. 1961. Das anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 3 vols. Berlin: Mann, 1976, ISBN 3-7861-2241-5

- Hillenbrand, Robert. 1994. Islamic Architecture: Form, function and meaning. NY: Columbia University Press. (see Chapter VI for an in depth overview of the caravanserai).

- Kiani, Mohammad Yusef. 1976. Caravansaries in Khorasan Road. Reprinted from: Traditions Architecturales en Iran, Tehran, No. 2 & 3, 1976.

- Schutyser, Tom. 2012. Caravanserai: Traces, Places, Dialogue in the Middle East. Milan: 5 Continents Editions, ISBN 978-88-7439-604-7

- Yavuz, Aysil Tükel. 1997. The Concepts that Shape Anatolian Seljuq Caravansara. In: Gülru Necipoglu (ed). 1997. Muqarnas XIV: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 80–95. [archnet.org/library/pubdownloader/pdf/8967/doc/DPC1304.pdf Available online as a PDF document, 1.98 MB]

External links

| Look up caravanserai in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caravanserais. |

- Shah Abbasi Caravanserai, Tishineh

- Caravansara Pictures

- Consideratcaravanserai.net, Texts and photos on research on caravanserais and travel journeys in Middle East and Central Asia.

- Caravanserais (Kervansaray) in Turkey

- The Seljuk Han in Anatolia

.jpg.webp)