David Josiah Brewer

David Josiah Brewer (June 20, 1837 – March 28, 1910) was an American jurist and an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States for 20 years.

David Josiah Brewer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office December 18, 1889 – March 28, 1910 | |

| Nominated by | Benjamin Harrison |

| Preceded by | Stanley Matthews |

| Succeeded by | Charles Evans Hughes |

| Judge of the United States Circuit Court for the Eighth Circuit | |

| In office March 31, 1884 – December 18, 1889 | |

| Nominated by | Chester Arthur |

| Preceded by | George McCrary |

| Succeeded by | Henry Caldwell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 20, 1837 Smyrna, Ottoman Empire (now İzmir, Turkey) |

| Died | March 28, 1910 (aged 72) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Louise Landon

(m. 1861; died 1898)Emma Mott (m. 1901) |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | Wesleyan University Yale University (BA) Albany Law School (LLB) |

Early life

Brewer was born to American missionaries Emilia Field Brewer and Rev. Josiah Brewer, who at the time of his birth were running a school for Greeks in Smyrna, Ottoman Empire; Emilia Brewer's brother Stephen Johnson Field, a future Supreme Court colleague of Brewer, was living with the couple at the time.[1] His parents returned to the United States in 1838 and settled in Connecticut. Brewer attended college at Wesleyan University (1851–1854), where he was a member of the Mystical 7 Society, and he afterward attended Yale College, graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1856.[2][3][4] While at Yale, Brewer was a classmate of Chauncey Depew and Henry Billings Brown, and was "greatly influenced by the political scientist-protestant minister Theodore Dwight Woolsey."[1] After graduation, Brewer read law for one year in the office of his uncle David Dudley Field,[1] then enrolled at Albany Law School in Albany, New York, graduating in 1858.

Career

Upon graduating from law school, Brewer moved to Kansas City, Missouri and after attempting to start a law practice, left for Colorado in search of gold, returning empty-handed in 1859 to nearby Leavenworth, Kansas.[1] He was named Commissioner of the Federal Circuit Court in Leavenworth in 1861. He left that court to become a judge to the Probate and Criminal Courts in Leavenworth in 1862, and then changed courts again to become a judge to the First Judicial District of Kansas in 1865. He left that position in 1869 and became city attorney of Leavenworth. He was then elected to the Kansas Supreme Court in 1870, where he served for 14 years.[1]

On March 25, 1884, Brewer was nominated by President Chester A. Arthur to the United States circuit court for the Eighth Circuit, to a seat vacated by George Washington McCrary. This court later became the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. Brewer was confirmed by the United States Senate on March 31, and received commission the same day.

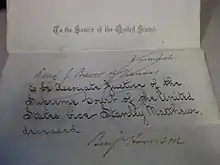

After 28 years on the bench, Brewer was nominated by Benjamin Harrison to the United States Supreme Court on December 4, 1889, to a seat vacated by Stanley Matthews.[1] Brewer was confirmed by the Senate on December 18, and received commission the same day, joining a court that included S. J. Field, his uncle. He served on the court for 20 years, until his death in 1910, being the last serving Supreme Court Justice appointed by President Harrison. In this regard, University of Texas professor and Supreme Court historian Lucas Powe has noted: "Brewer was one of the most influential justices [on] the court at the time. He was a vigorous defender of minority rights. In one case, he argued for stronger labor protections for women, while in other opinions he argued passionately for the rights of marginalized Chinese and Japanese immigrants."[5][6][7][8]

Brewer was an active member of the Supreme Court, writing often in both concurring and dissenting opinions. He was, in most cases, a moderate conservative. He was a major contributor to the doctrine of substantive due process, arguing that certain activities are entirely outside government control. In his time he frequently sided with the Court's majorities that struck down property rights restrictions.

Brewer was the author of the unanimous opinion of the Court in Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States (143 U.S. 457, 36 L.Ed. 226, 12 S. Ct. 511 February 29, 1892), which addressed a dispute over an employment contract between an Anglican priest and the titular church. Justice Brewer's statement in that opinion, "These, and many other matters which might be noticed, add a volume of unofficial declarations to the mass of organic utterances that this is a Christian nation" is often incorrectly cited as part of the controlling ruling in the matter, which is not the case. Indeed, Justice Brewer's book, The United States: A Christian Nation, published in 1905, contained the following passage:

But in what sense can [the United States] be called a Christian nation? Not in the sense that Christianity is the established religion or the people are compelled in any manner to support it. On the contrary, the Constitution specifically provides that 'congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.' Neither is it Christian in the sense that all its citizens are either in fact or in name Christians. On the contrary, all religions have free scope within its borders. Numbers of our people profess other religions, and many reject all. [...] Nor is it Christian in the sense that a profession of Christianity is a condition of holding office or otherwise engaging in public service, or essential to recognition either politically or socially. In fact, the government as a legal organization is independent of all religions.

Nevertheless, we constantly speak of this republic as a Christian nation—in fact, as the leading Christian nation of the world. This popular use of the term certainly has significance. It is not a mere creation of the imagination. It is not a term of derision but has a substantial basis—one which justifies its use. Let us analyze a little and see what is the basis.

Justice Brewer discusses numerous evidences from public and private life including citations from the Federal and Several state Constitutions before concluding as follows:

But I must not weary you. I could go on indefinitely, pointing out further illustrations both official and non-official, public and private; such as the annual Thanksgiving proclamations, with their following days of worship and feasting; announcements of days of fasting and prayer; the universal celebration of Christmas; the gathering of millions of our children in Sunday Schools, and the countless volumes of Christian literature, both prose and poetry. But I have said enough to show that Christianity came to this country with the first colonists; has been powerfully identified with its rapid development, colonial and national, and to-day exists as a mighty factor in the life of the republic. This is a Christian nation, ...

While Justice Brewer's decision was not a binding legal pronouncement reflecting an official acceptance of Christianity and did not say that its laws or policies should reflect solely Christian concerns and beliefs, he did outline the influence Christianity had on the history and culture of the United States. It was this influence that caused Brewer to state many times that this is a Christian nation.

Brewer temporarily took a leave from his Supreme Court duties to serve as president of the U.S. Commission on the Boundary Between Venezuela and British Guiana,[1] established by Congress to arbitrate in the Venezuela Crisis of 1895.

Brewer was the author of the unanimous opinion of the Court in Muller v. Oregon (1908) in support of a law restricting working hours for women. He was also the author of In re Debs, upholding federal injunctions to suppress labor strikes. Along with Justice Harlan, Brewer dissented in Giles v. Harris (1903), a case challenging grandfather clauses as applied to voting rolls.

In April 1896, due to the unexpected death of his daughter, Brewer left for his Leavenworth home on the day that Plessy v. Ferguson was argued before the Court, and did not participate in that 7-1 decision.[9][10] However, "[a]s a judge in Reconstruction era Kansas, he had authored one of the first judicial opinions upholding the right of an African-American citizen to vote in a general election, and as the superintendent of schools in Leavenworth, he had helped establish the first schools for blacks in the state."[11]

In 1904, he served as president of the Universal Congress of Lawyers and Jurists held in conjunction with that year's Louisiana Purchase Exposition.[1] In 1906, Brewer was one of the 30 founding members of the Simplified Spelling Board, founded by Andrew Carnegie to make English easier to learn and understand through changes in the English language.[12]

Bibliography

- Brewer, David J. (1897). The Pew to the Pulpit. New York City: Fleming H. Revell. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- Brewer, David J. (1905). American Citizenship. New York City: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- Brewer, David J. (1905). The United States: A Christian Nation. Philadelphia: John C. Winston. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- Brewer, David J. (1910). The Mission of the United States in the Cause of Peace. Boston: International School of Peace. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

See also

- List of Justices of the United States Supreme Court

References

- General

- Data drawn in part from the Supreme Court Historical Society and the Oyez Project.

- David Josiah Brewer at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Specific

- Hylton, J. Gordon (April 4, 2008). "Why David Josiah Brewer Is a Neglected Justice". 2008 Judicial Reputation Conference. Vanderbilt University Law School. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "Supreme Court Justices Who Are Phi Beta Kappa Members" (PDF). Phi Beta Kappa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- David Josiah Brewer; Edward Archibald Allen; William Schuyler (1899). "The World's best orations: from the earliest period to the present time". Books.google.com. p. 9. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

- "David Josiah Brewer". Robinsonlibrary.com. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

- "News & latest headlines from AOL". Aolnews.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-05. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2012-03-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Thepolitical Philosophy Of Supreme Court" (PDF). Libinfo.uark.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

- "David Josiah Brewer - Further Readings - Court, Rights, United, and Kansas - JRank Articles". Law.jrank.org. 1910-03-28. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

- "Plessy V. Ferguson | Findlaw". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

- Hylton, J. Gordon (Fall 1991). "The Judge Who Abstained in Plessy: Justice David Josiah Brewer and the Problem of Race". Mississippi Law Journal. Mississippi Bar Association. 61: 315.

- "Article: The Judge Who Abstained In Plessy v. Ferguson: Justice David Brewer And The Problem Of Race". Litigation-essentials.lexisnexis.com. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

- "Carnegie Assaults the Spelling Bee". The New York Times. March 12, 1906. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to David Josiah Brewer. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: David Josiah Brewer |

- Works by David Josiah Brewer at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about David Josiah Brewer at Internet Archive

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by George McCrary |

Judge of the United States Circuit Court for the Eighth Circuit 1884–1889 |

Succeeded by Henry Caldwell |

| Preceded by Stanley Matthews |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1889–1910 |

Succeeded by Charles Hughes |