Extraocular muscles

The extraocular muscles are the six muscles that control movement of the eye and one muscle that controls eyelid elevation (levator palpebrae). The actions of the six muscles responsible for eye movement depend on the position of the eye at the time of muscle contraction.

| Extraocular muscles | |

|---|---|

MRI scan showing lateral and medial rectus muscle. | |

| Details | |

| System | Visual system |

| Origin | Annulus of Zinn, maxillary and sphenoid bone |

| Insertion | Tarsal plate of upper eyelid, eye |

| Artery | Ophthalmic artery, lacrimal artery, infraorbital artery, anterior ciliary arteries, superior and inferior orbital veins |

| Nerve | Oculomotor, trochlear and Abducens nerve |

| Actions | See table |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Musculi externi bulbi oculi |

| MeSH | D009801 |

| TA98 | A04.1.01.001 |

| TA2 | 2041 |

| FMA | 49033 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

Structure

Since only a small part of the eye called the fovea provides sharp vision, the eye must move to follow a target. Eye movements must be precise and fast. This is seen in scenarios like reading, where the reader must shift gaze constantly. Although under voluntary control, most eye movement is accomplished without conscious effort. Precisely how the integration between voluntary and involuntary control of the eye occurs is a subject of continuing research.[1] It is known, however, that the vestibulo-ocular reflex plays an important role in the involuntary movement of the eye.

Origins and insertions

Four of the extraocular muscles have their origin in the back of the orbit in a fibrous ring called the annulus of Zinn: the four rectus muscles. The four rectus muscles attach directly to the front half of the eye (anterior to the eye's equator), and are named after their straight paths.[1] Note that medial and lateral are relative terms. Medial indicates near the midline, and lateral describes a position away from the midline. Thus, the medial rectus is the muscle closest to the nose. The superior and inferior recti do not pull straight back on the eye, because both muscles also pull slightly medially. This posterior medial angle causes the eye to roll with contraction of either the superior rectus or inferior rectus muscles. The extent of rolling in the recti is less than the oblique, and opposite from it.[1]

The superior oblique muscle originates at the back of the orbit (a little closer to the medial rectus, though medial to it), getting rounder as it[1] courses forward to a rigid, cartilaginous pulley, called the trochlea, on the upper, nasal wall of the orbit. The muscle becomes tendinous about 10mm before it passes through the pulley, turning sharply across the orbit, and inserts on the lateral, posterior part of the globe. Thus, the superior oblique travels posteriorly for the last part of its path, going over the top of the eye. Due to its unique path, the superior oblique, when activated, pulls the eye downward and laterally.[2]

The last muscle is the inferior oblique, which originates at the lower front of the nasal orbital wall, and passes under the LR to insert on the lateral, posterior part of the globe. Thus, the inferior oblique pulls the eye upward and laterally.[2][3][4]

The movements of the extraocular muscles take place under the influence of a system of extraocular muscle pulleys, soft tissue pulleys in the orbit. The extraocular muscle pulley system is fundamental to the movement of the eye muscles, in particular also to ensure conformity to Listing's law. Certain diseases of the pulleys (heterotopy, instability, and hindrance of the pulleys) cause particular patterns of incomitant strabismus. Defective pulley functions can be improved by surgical interventions.[5][6]

Blood supply

The extraocular muscles are supplied mainly by branches of the ophthalmic artery. This is done either directly or indirectly, as in the lateral rectus muscle, via the lacrimal artery, a main branch of the ophthalmic artery. Additional branches of the ophthalmic artery include the ciliary arteries, which branch into the anterior ciliary arteries. Each rectus muscle receives blood from two anterior ciliary arteries, except for the lateral rectus muscle, which receives blood from only one. The exact number and arrangement of these ciliary arteries may vary. Branches of the infraorbital artery supply the inferior rectus and inferior oblique muscles.

Nerve supply

| Cranial nerve | Muscle |

|---|---|

| Oculomotor nerve (N. III) |

Superior rectus muscle

Inferior rectus muscle Medial rectus muscle Inferior oblique muscle |

| Levator palpebrae superioris muscle | |

| Trochlear nerve (N. IV) |

Superior oblique muscle |

| Abducens nerve (N. VI) |

Lateral rectus muscle |

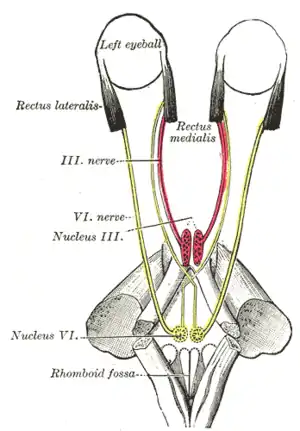

The nuclei or bodies of these nerves are found in the brain stem. The nuclei of the abducens and oculomotor nerves are connected. This is important in coordinating the motion of the lateral rectus in one eye and the medial action on the other. In one eye, in two antagonistic muscles, like the lateral and medial recti, contraction of one leads to inhibition of the other. Muscles show small degrees of activity even when resting, keeping the muscles taut. This "tonic" activity is brought on by discharges of the motor nerve to the muscle.[1]

Development

The extraocular muscles develop along with Tenon's capsule (part of the ligaments) and the fatty tissue of the eye socket (orbit). There are three centers of growth that are important in the development of the eye, and each is associated with a nerve. Hence the subsequent nerve supply (innervation) of the eye muscles is from three cranial nerves. The development of the extraocular muscles is dependent on the normal development of the eye socket, while the formation of the ligament is fully independent.

Function

Movements

Below is a table of each of the extraocular muscles and their innervation, origins and insertions, and the primary actions of the muscles (the secondary and tertiary actions are also included, where applicable).[7]

| Muscle | Innervation | Origin | Insertion | Primary action | Secondary action | Tertiary action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial rectus | Oculomotor nerve (inferior branch) |

Annulus of Zinn | Eye (anterior, medial surface) |

Adduction | ||

| Lateral rectus | Abducens nerve | Annulus of Zinn | Eye (anterior, lateral surface) |

Abduction | ||

| Superior rectus | Oculomotor nerve (superior branch) |

Annulus of Zinn | Eye (anterior, superior surface) |

Elevation | Incyclotorsion | Adduction |

| Inferior rectus | Oculomotor nerve (inferior branch) |

Annulus of Zinn | Eye (anterior, inferior surface) |

Depression | Excyclotorsion | Adduction |

| Superior oblique | Trochlear nerve | Sphenoid bone via the Trochlea |

Eye (posterior, superior, lateral surface) |

Incyclotorsion | Depression | Abduction |

| Inferior oblique | Oculomotor nerve (inferior branch) |

Maxillary bone | Eye (posterior, inferior, lateral surface) |

Excyclotorsion | Elevation | Abduction |

| Levator palpebrae superioris | Oculomotor nerve | Sphenoid bone | Tarsal plate of upper eyelid | Elevation/retraction

of the upper eyelid |

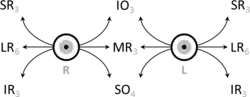

Movement coordination

Intermediate directions are controlled by simultaneous actions of multiple muscles. When one shifts the gaze horizontally, one eye will move laterally (toward the side) and the other will move medially (toward the midline). This may be neurally coordinated by the central nervous system, to make the eyes move together and almost involuntarily. This is a key factor in the study of strabismus, namely, the inability of the eyes to be directed to one point.

There are two main kinds of movement: conjugate movement (the eyes move in the same direction) and disjunctive (opposite directions). The former is typical when shifting gaze right or left, the latter is convergence of the two eyes on a near object. Disjunction can be performed voluntarily, but is usually triggered by the nearness of the target object. A "see-saw" movement, namely, one eye looking up and the other down, is possible, but not voluntarily; this effect is brought on by putting a prism in front of one eye, so the relevant image is apparently displaced. To avoid double vision from non-corresponding points, the eye with the prism must move up or down, following the image passing through the prism. Likewise conjugate torsion (rolling) on the anteroposterior axis (from the front to the back) can occur naturally, such as when one tips one's head to one shoulder; the torsion, in the opposite direction, keeps the image vertical.

The muscles show little inertia - a shutdown of one muscle is not due to checking of the antagonist, so the motion is not ballistic.[1]

Clinical significance

Examination

The initial clinical examination of the extraoccular eye muscles is done by examining the movement of the globe of the eye through the six cardinal eye movements. When the eye is turned out (temporally) and horizontally, the function of the lateral rectus muscle is tested. When the eye is turned in (nasally) and horizontally, the function of the medial rectus muscle is being tested. When turning the eye down and in, the inferior rectus is contracting. When turning it up and in the superior rectus is contracting. Paradoxically, turning the eye up and out uses the inferior oblique muscle, and turning it down and out uses the superior oblique. All of these six movements can be tested by drawing a large "H" in the air with a finger or other object in front of a patient's face and having them follow the tip of the finger or object with their eyes without moving their head. Having them focus on the object as it is moved in toward their face in the midline will test convergence, or the eyes' ability to turn inward simultaneously to focus on a near object.

To evaluate for weakness or imbalance of the muscles, a penlight is shone directly on the corneas. Expected normal results of the corneal light reflex is when the penlight's reflection is located in the centre of both corneas, equally.[8]

Gallery

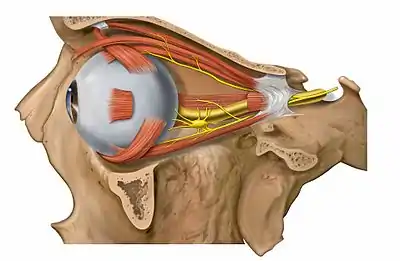

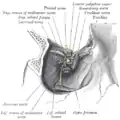

Nerves of the orbit. Seen from above.

Nerves of the orbit. Seen from above. Figure showing the mode of innervation of the Recti medialis and lateralis of the eye.

Figure showing the mode of innervation of the Recti medialis and lateralis of the eye. Dissection showing origins of right ocular muscles, and nerves entering by the superior orbital fissure.

Dissection showing origins of right ocular muscles, and nerves entering by the superior orbital fissure. View of the orbit from the front, with nerves and extraocular muscles.

View of the orbit from the front, with nerves and extraocular muscles. Extraocular muscles

Extraocular muscles

See also

References

- "eye, human."Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD 2009

- Ahmed HU (2002). "A case of mistaken muscles". BMJ. 324 (7343): 962. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7343.962. ISSN 0959-8138. S2CID 71166629.

- Carpenter, Roger H.S. (1988). Movements of the eyes (2nd ed., rev. and enl. ed.). London: Pion. ISBN 0-85086-109-8.

- Westheimer G, McKee SP (July 1975). "Visual acuity in the presence of retinal-image motion". J Opt Soc Am. 65 (7): 847–50. doi:10.1364/josa.65.000847. PMID 1142031.

- Demer JL (April 2002). "The orbital pulley system: a revolution in concepts of orbital anatomy". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 956: 17–32. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02805.x. PMID 11960790. S2CID 28173133.

- Demer JL (March 2004). "Pivotal role of orbital connective tissues in binocular alignment and strabismus: the Friedenwald lecture". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45 (3): 729–38, 728. doi:10.1167/iovs.03-0464. PMID 14985282.

- Yanoff, Myron; Duker, Jay S. (2008). Ophthalmology (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Mosby. p. 1303. ISBN 978-0323057516.

- Lewis SL, Heitkemper MM, Dirkson SR, O'Brien PG, Bucher L, Barry MA, Goldsworthy S, Goodridge D (2010). Medical-Surgical Nursing in Canada. Toronto: Elsevier Canada. p. 464. ISBN 9781897422014.

Further reading

- Eldra Pearl Solomon; Richard R. Schmidt; Peter James Adragna (1990). Human anatomy & physiology. Saunders College Publishing. ISBN 978-0-03-011914-9.

External links

- neuro/637 at eMedicine - "Extraocular Muscles, Actions"

- Atlas image: eye_13 at the University of Michigan Health System

- Animations of extraocular cranial nerve and muscle function and damage (University of Liverpool)