Félix Éboué

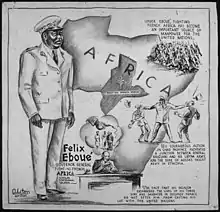

Adolphe Sylvestre Félix Éboué (French: [adɔlf silvɛstʁ feli ebwe]; 1 January 1884 – 17 May 1944) was a French colonial administrator and Free French leader. He was the first black French man appointed to a high post in the French colonies, when appointed as Governor of Guadeloupe in 1936.

Félix Éboué | |

|---|---|

Éboué welcomes Charles de Gaulle to Chad in October 1940 | |

| Governor of Guadeloupe | |

| In office 1936 – 1938 | |

| Personal details | |

| Pronunciation | French: [adɔlf silvɛstʁ feli ebwe] |

| Born | Adolphe Sylvestre Félix Éboué 1 January 1884 Cayenne, French Guiana |

| Died | 17 March 1944 (aged 60) Cairo, Egypt |

| Resting place | Panthéon, Paris, France 48°50′46″N 2°20′45″E |

| Spouse(s) | Eugenié Tell (1889–1971) |

| Relations | Léopold Sédar Senghor (son-in-law) |

| Alma mater | École nationale de la France d'Outre-Mer |

| Allegiance | |

As governor of Chad (part of French Equatorial Africa) during most of World War II, he helped build support for Charles de Gaulle's Free French in 1940,[1] leading to broad electoral support for the Gaullist faction after the war. He supported educated Africans and placed more in the colonial administration, as well as supporting preservation of African culture. He was the first black person to have his ashes placed at the Pantheon in Paris after his death in 1944.

Early life and education

Born in Cayenne, French Guiana, the grandson of slaves, Félix was the fourth of a family of five brothers. His father, Yves Urbain Éboué, was a gold digger, and his mother, Marie Josephine Aurélie Leveillé, was a shop owner born in Roura. She raised her sons in the Guiana Créole tradition.

Éboué won a scholarship to study at secondary school in Bordeaux. Éboué was also a keen footballer, captaining his school team when they travelled to games in both Belgium and England. He graduated in law from the École nationale de la France d'Outre-Mer (called École coloniale for short), one of the grandes écoles in Paris.[2]

Career

Éboué served in colonial administration in Oubangui-Chari for twenty years, and then in Martinique. In 1936 he was appointed governor of Guadeloupe, the first man of black African descent to be appointed to such a senior post anywhere in the French colonies.

Two years later, with conflict on the horizon, he was transferred to Chad, arriving in Fort Lamy on 4 January 1939. He was instrumental in developing Chadian support for the Free French in 1940. This ultimately gave Charles de Gaulle's faction control of the rest of French Equatorial Africa.[2]

New indigenous policy for the French empire

As governor of the whole of French Equatorial Africa between 1940 and 1944, Éboué published The New Indigenous Policy for French Equatorial Africa, which set out the broad lines of a new policy that advocated respect for African traditions, support for traditional leaders, the development of existing social structures and the improvement of working conditions. The document served as a basis for the Brazzaville conference of French colonial governors, held in 1944, that sought to introduce major improvements for the peoples of the colonies.[3]

He classified 200 educated Africans as "notable évolués" and reduced their taxes, as well as placing some Gabonese civil servants into positions of authority. He also took an interest in the careers of individuals who would later become significant in their own rights, including Jean-Hilaire Aubame and Jean Rémy Ayouné.

Personal life

Éboué married Eugénie Tell. In 1946 one of their daughters, Ginette, married Léopold Sédar Senghor, the poet and future president of independent Senegal.

In 1922, Éboué was initiated as a freemason at "La France Équinoxiale" lodge in Cayenne. During his life he frequented "Les Disciples de Pythagore" and "Maria Deraismes" lodges. He is considered to be the first freemason to have joined the Resistance.[4] Eugénie his wife was initiated at Droit Humain in Martinique[5] and his daughter Ginette at Grande Loge Féminine de France.[6]

Éboué died in 1944 of a stroke while in Cairo. After cremation, his ashes were placed in the Panthéon in Paris, where he was the first black French man to be honored in the manner.[2][7]

Legacy and honours

Éboué was awarded an Officer of the Legion of Honour, decorated in 1941 with the Cross of the Liberation and was made a member of the Council of the Order of the Liberation.

In 1961, the Banque Centrale des États de l’Afrique Équatoriale et du Cameroun (Central Bank of Equatorial African States and Cameroon) issued a 100-franc banknote featuring his portrait. The French colonies in Africa also brought out a joint stamp issue in 1945 honouring his memory.[8]

Within France, a square, Place Félix-Éboué, in 12th arrondissement of Paris is named for him, as is the adjacent Paris Métro station Daumesnil Félix-Éboué. A primary school in Le Pecq bears his name and offers bilingual English/French education. A small street near La Défense was named for him.

The main airport of Cayenne, French Guyana, which was previously named after the comte de Rochambeau, was named in his honor in 2012.

The Lycée Félix Éboué in N'Djamena is one of Chad's oldest secondary schools. Founded in 1958 as a general education college, it was made a lycée in 1960, the year that Chad became an independent country. In 2002, it was split into two separate schools, each with about 3000 students.[9]

References

- Shillington, Kevin (4 July 2013). Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set. 1 A–G. Routledge. p. 448. ISBN 978-1-135-45669-6. OCLC 254075497. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

There was much support for the Vichy regime among French colonial personnel, with the exception of Guianese-born governor of Chad, Félix Éboué, who in September 1940 announced his switch of allegiance from Vichy to the Gaullist Free French movement based in London. Encouraged by this support for his fledgling movement, Charles de Gaulle traveled to Brazzaville in October 1940 to announce the formation of an Empire Defense Council and to invite all French possessions loyal to Vichy to join it and continue the war against Germany; within two years, most did.

- Barry, Françoise. "ÉBOUÉ FÉLIX - (1884-1944)". Encyclopædia Universalis [en ligne]. Encyclopædia Universalis France. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ÉBOUÉ, Félix. "La nouvelle politique indigène pour l'Afrique équatoriale française". cvce.eu by uni.lu. Toulon: Office Français d'Édition. 08-11-1941. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- Dictionnaire universelle de la Franc-Maçonnerie, page 253 (Marc de Jode, Monique Cara and Jean-Marc Cara, ed. Larousse , 2011)

- Dictionnaire de la Franc-Maçonnerie, page 380 (Daniel Ligou, Presses Universitaires de France, 2006)

- Joseph Badila, La franc-maçonnerie en Afrique noire: un si long chemin vers la liberté, l'égalité, la fraternité, Detrad, 2004, p. 142)

- "Archives d'Outre-mer - 20 mai 1949 : Félix Éboué entre au Panthéon". le portail des Outre-Mer. France TV. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- https://www.catawiki.com/catalog/stamps/collections/2106857-1945-governor-general-felix-eboue?page=1&field=SO_45&order=a&external=0&view=g&page=1&vg=all&type=s&language=en&area_id=2106857&user_id=&stamp_filter=&filters%5Bin_wish_list%5D=&filters%5B7839%5D=&filters%5B7845%5D=&filters%5B7857%5D=&filters%5B7855%5D=&filters%5B7849%5D=&filters%5B8103%5D=&filters%5Byear_from%5D=&filters%5Byear_to%5D=&filters%5Btitle%5D=&filters%5Bsearch_key%5D=

- "Présentation du Lycée Félix Eboué I". Memoire Online. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

Further reading

- Weinstein, Brian (1972). Éboué. Oxford University Press: New York. ISBN 0195014677.