Field lacrosse

Field lacrosse is a full contact outdoor men's sport played with ten players on each team. The sport originated among Native Americans, and the modern rules of field lacrosse were initially codified by Canadian William George Beers in 1867. Field lacrosse is one of three major versions of lacrosse played internationally. The other versions, women's lacrosse (established in the 1890s) and box lacrosse (originated in the 1930s), are played under significantly different rules.

Kyle Harrison advancing, pursued by an opponent | |

| Highest governing body | World Lacrosse |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | Lax |

| First played | As early as the 12th century C.E., North America Codified in 1867 |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Full contact |

| Team members | 10 per team, including goaltender |

| Equipment | Ball, stick, helmet, gloves, shoulder pads, arm pads |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | Summer Olympics in 1904 and 1908. Demonstrated in 1928, 1932, and 1948 |

The object of the game is to use a lacrosse stick, or crosse, to catch, carry, and pass a solid rubber ball in an effort to score by shooting the ball into the opponent's goal. The triangular head of the lacrosse stick has a loose net strung into it that allows the player to hold the lacrosse ball. In addition to the lacrosse stick, players are required to wear a certain amount of protective equipment. Defensively the object is to keep the opposing team from scoring and to dispossess them of the ball through the use of stick checking and body contact. The rules limit the number of players in each part of the field. It is sometimes referred to as the "fastest sport on two feet".

Lacrosse is governed internationally by the 62-member World Lacrosse, which sponsors the World Lacrosse Championships once every four years. A former Olympic sport, attempts to reinstate it to the Olympics have been hampered by insufficient international participation and the lack of standard rules between the men's and women's games. Field lacrosse is played semi-professionally in North America by Major League Lacrosse and professionally by the Premier Lacrosse League. It is also played on a high amateur level by the National Collegiate Athletic Association in the United States, the Australian Senior Lacrosse Championship series, and the Canadian University Field Lacrosse Association.

History

Lacrosse is a traditional Native American game.[1][2] According to Native American beliefs, playing lacrosse is a spiritual act used for healing and giving thanks to the "Creator". Another reason to play the game is to resolve minor conflicts between tribes that were not worth going to war for, thus the name "little brother of war".[3] These games could last several days and as many as 100 to 1,000 men from opposing villages or tribes played on open plains, between goals ranging from 500 yards (460 m) to several miles apart.[4][5]

The first Europeans to observe it were French Jesuit missionaries in the St. Lawrence Valley in the 1630s.[1][2] The name "lacrosse" comes from their reports, which described the players' sticks as like a bishop's crosier—la crosse in French.[4][6] The Native American tribes used various names: in the Onondaga language it was called dehuntshigwa'es ("they bump hips" or "men hit a rounded object"); da-nah-wah'uwsdi ("little war") to the Eastern Cherokee; in Mohawk, tewaarathon ("little brother of war"); and baggataway in Ojibwe.[7][8][9] Variations in the game were not limited to the name. In the Great Lakes region, players used an entirely wooden stick, while the Iroquois stick was longer and was laced with string, and the Southeastern tribes played with two shorter sticks, one in each hand.[6][10]

In 1867, Montreal Lacrosse Club member William George Beers codified the modern game. He established the Canadian Lacrosse Association and created the first written rules for the game, Lacrosse: The National Game of Canada. The book specified field layout, lacrosse ball dimensions, lacrosse stick length, number of players, and number of goals required to determine the match winner.[6]

Rules

Field lacrosse involves two teams, each competing to shoot a lacrosse ball into the opposing team's goal. A lacrosse ball is made out of solid rubber, measuring 7.75 to 8 inches (19.7–20 cm) in circumference and weighing 5 to 5.25 ounces (140–149 g). Each team plays with ten players on the field: a goalkeeper; three defenders in the defensive end; three midfielders free to roam the whole field; and three attackers attempting to score goals in the offensive end. Players are required to wear some protective equipment, and must carry a lacrosse stick (or crosse) that meets specifications. Rules dictate the length of the game, boundaries, and allowable activity. Penalties are assessed by officials for any transgression of the rules.[11]

The game has undergone significant changes since Beers' original codification. In the 1930s, the number of players on the field per team was reduced from twelve to ten, rules about protective equipment were established, and the field was shortened.[12][13]

Playing area

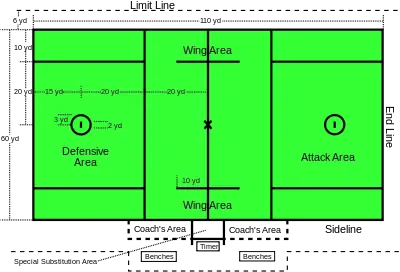

A standard lacrosse field is 110 yards (100 m) in length from each endline, and 60 yards (55 m) in width from the sidelines.[14][15]

Field lacrosse goals are centered between each sideline, positioned 15 yards (14 m) from each endline and 80 yards (73 m) apart from one another. Positioning the goals well within the endlines allows play to occur behind them. The goal is 6 feet (1.8 m) wide by 6 feet (1.8 m) tall, with nets attached in a pyramid shape. Surrounding each goal is a circular area known as the "crease," measuring 18 feet (5.5 m) in diameter.[15]

If a player enters the "crease" while shooting toward the goal, the referee will call a foul and the ball gets turned over to the other team.

A pair of lines, 20 yards (18 m) from both the midfield line and each goal line, divides the field into three sections. From each team's point of view, the one nearest its own goal is its defensive area, then the midfield area, followed by the attack or offensive area. These trisecting lines are called "restraining lines." A right angle line is marked 10 yards (9.1 m) from each sideline connecting each endline to the nearer restraining line, creating the "restraining box."[15][16] If an official deems that a team is "stalling," that is not moving with offensive purpose while controlling the ball, the possessing team must keep the ball within the offensive restraining box to avoid a loss-of-possession penalty.[17]

Field markings dictate player positioning during a face-off. A face-off is how play is started at the beginning of each period and after each goal. During a face-off, there are six players (without considering goalkeepers) in each of the areas defined by the restraining lines. Three midfielders from each team occupy the midfield area, while three attackmen and three of the opposing team's defensemen occupy each offensive area. These players must stay in these areas until possession is earned by a midfielder or the ball crosses either restraining line. Wing areas are marked on the field on the midfield line 10 yards (9.1 m) from each sideline. This line indicates where the two nonface-off midfielders per team lineup during a face-off situation. These players may position themselves on either side of the midfield line.[15] During a face-off, two players lay their sticks horizontally next to the ball, head of the stick inches from the ball and the butt-end pointing down the midfield line. Once the official blows the whistle to start play, the face-off midfielders scrap for the ball to earn possession and the other midfielders advance to play the ball. If possession is won by the face-off player, he may move the ball himself or pass to a teammate.[11]

The rules also require that substitution areas, a penalty box, coaches area, and team bench areas be designated on the field.[15]

Equipment

A field lacrosse player's equipment includes a lacrosse stick, and protective equipment, including a lacrosse helmet with face mask, lacrosse gloves, and arm and shoulder pads. Players are also required to wear mouthguards and athletic supporter with cup pocket and protective cup.[11] However, field players in the MLL and the PLL are not required to wear shoulder pads.

Each player carries a lacrosse stick measuring 40 to 42 inches (1.0–1.1 m) long (a "short crosse"), or 52 to 72 inches (1.3–1.8 m) long (a "long crosse"). In most modern circles the word crosse has been replaced by "stick" and the terms "short stick" and "long stick" or "pole" are used. On each team up to four players at a time may use a long crosse: the three defensemen and one midfielder. The crosse is made up of the head and the shaft (or handle). The head is roughly triangular in shape and is loosely strung with mesh or leathers and nylon strings to form a "pocket" that allows the ball to be caught, carried, and thrown. In field lacrosse, the pocket of the crosse is illegal if the top of the ball, when placed in the head of the stick, is below the bottom of the stick's sidewall.

The maximum width of the head at its widest point must be between 6 and 10 inches (15–25 cm).[14][15] From 1.25-inches up from the bottom of the head, the distance between the sidewalls of the crosse must be at least 3 inches. Most modern sticks have a tubular metal shaft, usually made of aluminum, titanium, or alloys, while the head is made of hard plastic. Metal shafts must have a plastic or rubber cap at the end.

The sport's growth has been hindered by the cost of a player's equipment: a uniform, helmet, shoulder pads, hand protection, and lacrosse sticks. Many players have at least two lacrosse sticks prepared for use in any contest.[18] Traditionally players used sticks made by Native American craftsman. These were expensive and, at times, difficult to find.[19][20] The introduction of the plastic heads in the 1970s gave players an alternative to the wooden stick,[4] and their mass production has led to greater accessibility and expansion of the sport.[21]

Goalkeeper

.jpg.webp)

The goalkeeper's responsibility is to prevent the opposition from scoring by directly defending the 6-foot-wide (1.8 m) by 6-foot-tall (1.8 m) goal.[15] A goalkeeper needs to stop shots that are capable of reaching over 100 miles per hour (160 km/h), and is responsible for directing the team's defense.[22][23]

Goalkeepers have special privileges when they are in the crease, a circular area surrounding each goal with a radius of 9 feet (2.7 m). Offensive players may not play the ball or make contact with the goalkeeper while he is in the crease. Once a goalkeeper leaves the crease, he loses these privileges.[24]

A goalkeeper's equipment differs from other players'. Instead of shoulder pads and elbow pads, the goalkeeper wears a chest protector. He also wears special "goalie gloves" that have extra padding on the thumb to protect from shots. The head of a goalkeeper's crosse may measure up to 15 inches (38 cm) wide, significantly larger than field players'.[15]

Defensemen

A defenseman is a player position whose responsibility is to assist the goalkeeper in preventing the opposing team from scoring. Each team fields three defensemen. These players generally remain on the defensive half of the field.[25] Unless a defenseman gets the ball and chooses to run up the field and try to score or pass, by doing this they will need to cross the midfield line and signal one midfielder to stay back. A defenseman carries a long crosse which provides an advantage in reach for intercepting passes and checking.[26][27]

Tactics used by defensemen include body positioning and checking. Checking is attempting to dispossess the opposition of the ball through body or stick contact. A check may include a "poke check", where a defenseman thrusts his crosse at the top hand or crosse of the opponent in possession of the ball (similar to a billiards shot), or a "slap check", where a player applies a short, two-handed slap to the hand or crosse of the opponent in possession of the ball.[28] A "body check" is allowed as long as the ball is in possession or a loose ball is within five yards of the opposing player and the contact is made to the front or side of the torso of the opposing player.[29] Defensemen preferably remain in a position relative to their offensive counterpart known as "topside", which generally means a stick and body position that forces a ball carrier to go another direction, usually away from the goal.[30]

Midfielders

Midfielders contribute offensively and defensively and may roam the entire playing area. Each team fields three midfielders at a time. One midfielder per team may use a long crosse,[25] and in this case is referred to as a "long-stick midfielder."[31] Long-stick midfielders are normally used for defensive possessions and face-offs but can participate in offense as long as they are not subbed off.

Over time, the midfield position has developed into a position of specialties. During play, teams may substitute players in and out freely, a practice known as "on the fly" substitution. The rules state that substitution must occur within the designated exchange area in front of the players' bench.[11] Teams frequently rotate the midfielder specialists off and on the field depending on the ball possession. Some teams have a designated face-off midfielder, referred to as a "fogo" midfielder (an acronym for "face-off and get-off"), who takes the majority of face-offs and is quickly substituted after the face-off.[32] Some teams also designate midfielders as "offensive midfielders" or "defensive midfielders" depending on their strengths and weaknesses.

Attackmen

Each team fields three attackmen at a time, and these players generally remain on the offensive half of the field.[25] An attackman uses a short crosse.[11]

Duration and tie-breaking methods

Duration of games depends upon the level of play. In international competition, college lacrosse, and Major League Lacrosse, the total playing time is 60 minutes, composed of four 15-minute quarters, plus a 15-minute intermission at halftime.[14][33] High school games typically consist of four 12-minute quarters but can be played in 30-minute halves, while youth leagues may have shorter games.[11] The clock typically stops during all dead ball situations such as between goals or if the ball goes out of bounds. The method of breaking a tie generally consists of multiple overtime periods of 5 minutes (4 in NCAA play, 10 in [MLL/PLL]) in which whoever scores a goal is awarded a sudden victory. A quicker variant of the sudden victory is the Braveheart method in which each team sends out one player and one goalie; it is then sudden victory.[33][34] International lacrosse plays two straight 5-minute overtime periods, and then applies the sudden victory rule if the score is still tied.[14]

Ball movement and out of play

Teams must advance the ball or be subjected to loss of possession. Once a team gains possession of the ball in their defensive area, they must move the ball over the midfield line within 20 seconds. If the goalkeeper has possession of the ball in the crease he must pass the ball or vacate the area within four seconds. Failure by the goalkeeper to leave the crease will result in the opposite team being given possession just outside the restraining box.[11] Once the ball crosses the midfield line, a team has 10 seconds to move the ball into the offensive area designated by the restraining box or forfeit possession to their opponents.[24] The term used to define moving the ball from the defensive to offensive area is to "clear" the ball. Offensive players are responsible for "riding" opponents, in other words attempting to deny the opposition a free "clear" of the ball over the midfield line.[11]

If a ball travels outside of the playing area, play is restarted by possession being awarded to the opponents of the team which last touched the ball, unless the ball goes out of bounds due to a shot or a deflected shot. In that case, possession is awarded to the player that is closest to the ball when it leaves the playing area.[11][14]

Penalties

For most fouls, the offending player is sent to the penalty box and his team has to play without him and with one fewer player for a short amount of time. Penalties are classified as either personal fouls or technical fouls.[17][29] Personal fouls are of a more serious nature and are generally penalised with a 1-minute suspension. Technical fouls are violations of the rules that are not as serious as personal fouls, and are penalised for 30 seconds or a loss of possession. Occasionally a longer penalty may be assessed for more severe infractions. Players penalised for 6 personal fouls must sit out the game.[11] The penalised team is said to be playing man down defense while the other team is on the man up, or playing "extra man offence." During a typical game, each team will have three to five extra man offence opportunities.[35]

Personal fouls

Personal fouls (PF) include slashing, tripping, illegal body checking, cross checking, unsportsmanlike conduct, unnecessary roughness, and equipment violations. While a stick-check (where a player makes contact with the opposition player's stick in order to knock the ball loose) is legal, a slashing violation is called when a player viciously makes contact with an opposing player or his stick. An illegal body check penalty is called for any contact where the ball is further than 5 yards (4.6 m) for high school and 3 yards (2.7 m)[36] for youth from the contact, the check is from behind, above the shoulders or below the knees, or was avoidable after the player has released the ball. Cross checking, where a player uses the shaft of his stick to push the opposition player off balance, is illegal in field lacrosse. Both unsportsmanlike conduct and unnecessary roughness are subject to the officiating crew's discretion, while equipment violations are governed strictly by regulations.[29] Any deliberate intent to injure opponents risks immediate disqualification. The substitute must serve out the 30 seconds.

Technical fouls

Technical fouls include holding, interference, pushing, illegal offensive screening (usually referred to as a "moving pick"), "warding off", stalling, and off-sides. A screen, as employed in basketball strategy, is a blocking move by an offensive player, by standing beside or behind a defender, to free a teammate to shoot, or receive a pass; as in basketball players must remain stationary when screening. Warding off occurs when an offensive player uses his free hand to control the stick of an opposing player.

Offside has a unique implementation in field lacrosse.[37] Instituted with rule changes in 1921, it limits the number of players that are allowed on either side of the midfield line.[13] Offside occurs when there are fewer than three players on the offensive side of the midfield line or when there are fewer than four players on the defensive half of the midfield line (note: if players are exiting through the special-substitution area, it is not to be determined an offside violation).[24]

A technical foul requires that the defenseman who fouled a player on the opposing team be placed in the penalty box for 30 seconds. As with a personal foul, until the penalty time expires, no replacement for the player is allowed and the team must play one man short. The player (or a replacement) is allowed to reenter the game once the time in the penalty box is over and the team is thus once again at full strength.

Domestic competition

College lacrosse, a spring sport in the United States, saw its earliest program established by New York University in 1877.[38] The first intercollegiate tournament was held in 1881 featuring four teams: New York University, Princeton University, Columbia University, and Harvard University. This tournament was won by Harvard.[6][39] The United States Intercollegiate Lacrosse Association (USILA) was created in 1885, and awarded the inaugural Wingate Memorial Trophy to the University of Maryland as national champions in 1936. The award was presented to the team (or teams) with the best record until the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) instituted a playoff system in 1971.[40][41] The NCAA sponsored its premier Men's Lacrosse Championship with the 1971 tournament where Cornell University defeated University of Maryland in the final.[42] In addition to the three divisions in the NCAA, college lacrosse in the United States is played by non-varsity Men's Collegiate Lacrosse Association and National College Lacrosse League club teams.[43][44][45]

Lacrosse was first witnessed in England, Scotland, Ireland and France in 1867 when a team of Native Americans and Canadians traveled to Europe to showcase the sport. The year after, the English Lacrosse Association was established.[6] In 1876, Queen Victoria attended an exhibition game and was impressed, saying, "The game is very pretty to watch."[46] Throughout Europe, lacrosse is played by numerous club teams and is overseen by the European Lacrosse Federation.[47] Lacrosse was brought to Australia in 1876.[48] The country sponsors various competitions among its states and territories that culminate in the annual Senior Lacrosse Championship tournament.[48]

In 1985, the Canadian University Field Lacrosse Association (CUFLA) was established, with twelve universities in the Ontario and Quebec provinces competing in the intercollegiate league. The league plays its season during the autumn. Unlike the NCAA, the CUFLA allows players that are professional box lacrosse players in the National Lacrosse League to participate, stating that "although stick skills are identical, the game play and rules are different".[49]

Professional field lacrosse made its first appearance in 1988 with the formation of the American Lacrosse League, which folded after five weeks of play.[50] In 2001, professional field lacrosse resurfaced with the inception of Major League Lacrosse (MLL),[51] whose teams, based in the United States and Canada, play during the summer.[52] The MLL modified its rules from the established field lacrosse rules of international, college, and high school programs. To increase scoring, the league employed a sixty-second shot clock, a two-point goal for shots taken outside a designated perimeter, and reduced the number of long sticks to three rather than the traditional four. Prior to the 2009 MLL season, after eight seasons, the league conformed to traditional field lacrosse rules and allowed a fourth long crosse.[31][53] In 2018, the Premier Lacrosse League launched with 140 players leaving the MLL to form a league with higher media exposure, salaries, healthcare, licensing access, and other benefits. These 140 players consisted of 86 All-Americans, 25 members of the U.S. national team, and 10 former Tewaaraton Award winners. [54]

International competition

World Lacrosse is the international governing body of lacrosse and it oversees field, women's and box lacrosse competitions. In 2008, the International Lacrosse Federation and the International Federation of Women's Lacrosse Associations merged to form the Federation of International Lacrosse.[55] The former International Lacrosse Federation was founded in 1974 to promote and develop the game of men's lacrosse throughout the world. In May 2019, FIL changed its name to World Lacrosse.[56]World Lacrosse sponsors the World Lacrosse Championship and Under-19 World Lacrosse Championships which are played under field lacrosse rules. It also oversees the World Indoor Lacrosse Championship played under box lacrosse rules, and the Women's Lacrosse World Cup and an under-19 championship under women's lacrosse rules.[55]

Olympic Games

Lacrosse at the Olympics was a medal-earning sport in the 1904 Summer Olympics and the 1908 Summer Olympics.[57] In 1904, three teams competed in the games held in Saint Louis, Missouri. Two Canadian teams, the Winnipeg Shamrocks and a team of Mohawk people from the Iroquois Confederacy, and an American team represented by the local St. Louis A.A.A. lacrosse club participated, and the Winnipeg Shamrocks captured the gold medal.[58][59] The 1908 games held in London, England, featured only two teams, representing Canada and Great Britain. The Canadians again won the gold medal in a single championship match by a score of 14–10.[60]

.jpg.webp)

In the 1928 Summer Olympics, 1932 Summer Olympics, and the 1948 Summer Olympics, lacrosse was a demonstration sport.[61] The 1928 Olympics featured three teams: the United States, Canada, and Great Britain.[62] The 1932 games featured a three-game exhibition between a Canadian All-star team and the United States.[63] The United States was represented by Johns Hopkins Blue Jays lacrosse in both the 1928 and 1932 Olympics. In order to qualify, the Blue Jays won tournaments in the Olympic years to represent the United States.[64][65] The 1948 games featured an exhibition by an "All-England" team organized by the English Lacrosse Union and the collegiate lacrosse team from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute representing the United States. This exhibition ended in a 5–5 tie.[66]

There are obstacles to reestablishing lacrosse as an Olympic sport. One hurdle was resolved in 2008, when the international governing bodies for men's and women's lacrosse merged to form the Federation of International Lacrosse, which was later renamed World Lacrosse.[67] Another obstacle is insufficient international participation. In order to be considered as an Olympic sport the game must be played on four continents, and with at least a total of 75 countries participating. According to one US Lacrosse representative in 2004, "it’ll take 15-20 years for us to get there."[68] For the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia and 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney, Australia, efforts were made to include lacrosse as an exhibition sport, but these failed.[65][68]

World Lacrosse Championships

The World Lacrosse Championship began as a four-team invitational tournament in 1967 sanctioned by the International Lacrosse Federation.[68] The 2006 World Lacrosse Championship featured a record twenty-one competing nations. The 2010 World Lacrosse Championship took place in Manchester, England. Only United States, Canada, and Australia have finished in the top two places of this tournament.[48] Since 1990, the Iroquois Nationals, a team consisting of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy members, have competed in international competition. This team is the only Native American team sanctioned to compete in any men's sport internationally.[69] The Federation of International Lacrosse also sanctions the Under-19 World Lacrosse Championships. The 2008 Under-19 World Lacrosse Championships included twelve countries, with three first-time participants: Bermuda, Finland, and Scotland.[70][71]

Other regional international competitions are played including the European Lacrosse Championships, sponsored by the twenty-one member European Lacrosse Federation, and the eight team Asian Pacific Lacrosse Tournament.[48][72]

Attendance records

Lacrosse attendance has grown with the sport's popularity.[73] The 2008 NCAA Division I Men's Lacrosse Championship was won by Syracuse University, beating Johns Hopkins University 13–10, in front of a title game record crowd of 48,970 fans at Gillette Stadium.[74] The 2007 NCAA Division I Men's Lacrosse Championship weekend held at M&T Bank Stadium in Baltimore, Maryland, was played in front of a total crowd of 123,225 fans for the three-day event.[75] The current attendance record for a regular season lacrosse-only event was set by the 2009 Big City Classic, a triple-header at Giants Stadium which drew 22,308 spectators.[76] The Denver Outlaws hold the professional field lacrosse single-game attendance record by playing July 4, 2015 in front of 31,644 fans.[77]

At the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles, California, over 145,000 spectators watched the three-game series between the United States and Canada, including 75,000 people who witnessed the first game of the series while in attendance to watch the final of the marathon.[63][64][65]

References

Footnotes

- Vennum, p. 9

- Liss, p. 13.

- Rock, Tom (November–December 2002). "More Than a Game". Lacrosse Magazine. US Lacrosse. Archived from the original on May 25, 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- "Lacrosse History". STX Lacrosse. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- Vennum, p. 183

- Pietramala, pp. 8-10

- Hochswender, Woody (April 20, 2008). "Growing Fast, Lacrosse Brings Out the Gladiator". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- Byers, Jim (Jul 22, 2006). "Iroquois keeping the faith". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 2012-04-16. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- Hoxie, Frederick E. (1996). Encyclopedia of North American Indians. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 323. ISBN 0-395-66921-9. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- Vennum Jr., Thomas. "The History of Lacrosse". US Lacrosse. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "Men's Lacrosse 2017 and 2018 Rules" (PDF). National Collegiate Athletic Association. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- Fisher, pp. 131-132

- Pietramala, p. 14

- "2017-2018 Rules of Men's Field Lacrosse" (PDF). Federation of International Lacrosse. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- NCAA Rulebook, Rule 1

- Morris, p. 29

- NCAA Rulebook, Rule 6

- Fisher, p. 163

- Fisher, p. 258

- Vennum, p. 286

- Fisher, p. 262

- Donovan, Mark (April 25, 1977). "Joy Is Having No Red Bruises". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- Pietramala, p. 130

- NCAA Rulebook, Rule 4

- NCAA Rulebook, Rule 2

- Morris, p. 39

- Pietramala, p. 154

- Pietramala, p. 113

- NCAA Rulebook, Rule 5

- LAXICON - the Lacrosse Dictionary

- "League announces expansion of rosters to 19 and addition of fourth long crosse for 2009". Inside Lacrosse. October 22, 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-10-25. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- Yeager, John M (2005). Our Game: The Character and Culture of Lacrosse. NPR Inc. pp. 17–18. ISBN 1-887943-99-4. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- NCAA Rulebook, Rule 3

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-12-27. Retrieved 2013-11-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Pietramala, p. 151

- "How it Works: Illegal Body Checking Rule in Boys Lacrosse". US Lacrosse. 2015-10-13. Retrieved 2020-03-13.

- Pietramala, p. 35

- Pietramala, p. 4

- Lydecker, Irving B. (May 23, 1925). "Lydecker tells history of lacrosse from time of Indian to present day". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- Pietramala, pp. 15-16

- John, Forbes (December 7, 1969). "Playoff to Determine Champion Of U.S. College Lacrosse in '71". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- Carry, Peter (June 14, 1971). "Big Red Votes Itself No. 1". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- Pietramala, p. 19

- "About". Men’s Collegiate Lacrosse Association. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- "Eligibility". National College Lacrosse League. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- Thompson, Jonathan (October 14, 2001). "Your sport Lacrosse; Think it sounds a bit soft? Think again". The Independent Sunday. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- "Map of European Clubs". European Lacrosse Federation. Archived from the original on 2009-03-05. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- "This is Lacrosse Australia" (PDF). Lacrosse Australia. July 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-27.

- "FAQ's". Canadian University Field Lacrosse Association. Archived from the original on May 19, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- Fisher, pp. 289-290

- "History". Major League Lacrosse. Archived from the original on 2006-12-16. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- Kelly, Morgan (March 3, 2009). "Canadian players thrilled to join Nationals". Major League Lacrosse. Archived from the original on March 22, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- "Rules". Major League Lacrosse. Archived from the original on 2009-02-23. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- "PAUL RABIL'S PREMIER LACROSSE LEAGUE LAUNCHES". U.S. Lacrosse Magazine. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- Logue, Brian (August 13, 2008). "ILF, IFWLA Merge to Form FIL". Lacrosse Magazine. US Lacrosse. Archived from the original on February 23, 2009. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- Mackay, Duncan (5 May 2019). "Lacrosse launches new name and logo at SportAccord Summit as continues Olympic push". Inside the Games. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- "Lacrosse results from the 1904 & 1908 Summer Olympics". DatabaseOlympics.com. Archived from the original on 2007-02-05. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- "1904 Winnipeg Shamrocks". The Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame & Museum. Archived from the original on 2008-11-09. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- Brownell, Susan (2008). The 1904 Anthropology Days and Olympic Games. University of Nebraska Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-8032-1098-1. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- Owen, David (April 25, 2008). "David Owen on the 1908 Olympic celebration". Inside the Games. Archived from the original on May 2, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- "Olympic sports of the past". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- "Official Report Of The Olympic Games Of 1928 Celebrated At Amsterdam" (PDF). The Netherlands Olympic Committee. 1928. pp. 899–903. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- "Official Report Of The Xth Olympiade Committee in Los Angeles 1932" (PDF). Xth Olympiade Committee. 1932. pp. 763–766. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 7, 2010. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- Pietramala, pp. 201-202

- "Lacrosse on the Olympic Stage". Lacrosse Magazine. US Lacrosse. September–October 2004. Archived from the original on 2007-10-23. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- "1948 Official Olympic ReportThe Official Report of the Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad" (PDF). Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad. 1948. pp. 716–717. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- "Historic Meeting Moves IFWLA and ILF Closer Together". US Lacrosse. Archived from the original on 2008-09-07. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- "International Lacrosse History". US Lacrosse. Archived from the original on 2008-09-20. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- Fryling, Kevin (July 27, 2006). "Nike deal promotes Native American wellness, lacrosse". University of Buffalo Reporter. Archived from the original on September 6, 2006. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- "2008 Under-19 World Lacrosse Championships". International Lacrosse Federation. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- McLaughlin, Kiel (July 1, 2008). "U-19 World Games Breakdown: Red Division". Inside Lacrosse. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- "Welcome". European Lacrosse Federation. Archived from the original on 2009-01-13. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- Wolff, Alexander (April 25, 2005). "Get On The Stick". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on June 21, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- "Syracuse takes 13-10 win over Johns Hopkins for 10th NCAA title". Inside Lacrosse. May 26, 2008. Archived from the original on May 28, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- "Attendance Figures for the NCAA Men's Championships". Lax Power. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- Inside Lacrosse Big City Classic sets attendance record for regular-season lacrosse event Archived April 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Inside Lacrosse, April 6, 2009.

- "MLL News & Notes Week 9, 2008". Major League Lacrosse. Archived from the original on 2010-01-03. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

Bibliography

- Fisher, Donald M. (2002). Lacrosse: A History of the Game. JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-6938-2. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- Liss, Howard (1970). Lacrosse. Funk & Wagnalls.

- Morris, Michael (2005). The Confident Coach's Guide to Teaching Lacrosse. Globe Pequot. ISBN 1-59228-588-0. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- "Men's Lacrosse 2017 and 2018 Rules" (PDF). National Collegiate Athletic Association. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- Pietramala, David G.; Grauer, Neil A.; Scott, Bob; Van Rensselaer, James T. (2006). Lacrosse: Technique and Tradition. JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-8410-1. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- Vennum, Thomas; Vennum, Jr, Thomas (2008). American Indian Lacrosse: Little Brother of War. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8764-2. Retrieved 2009-03-27.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Field lacrosse. |

![]() Works related to Lacrosse: The National Game of Canada at Wikisource

Works related to Lacrosse: The National Game of Canada at Wikisource

- This is Lacrosse - video presented by US Lacrosse