Finno-Ugric peoples

The Finno-Ugric peoples or Finno-Ugrian peoples, are the peoples of Northeast Europe, North Asia and the Carpathian Basin who speak Finno-Ugric languages – that is, speakers of languages of the Uralic family apart from the Samoyeds. Many Finno-Ugric peoples are surrounded by speakers of languages belonging to other language families. The concept of Finno-Ugric was originally a linguistic rather than ethnic one, but a sense of ethnic fraternity between Finno-Ugric–speaking peoples, especially Baltic Finns, developed during the 20th century.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~26,505,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 9,982,000 | |

| 5,500,000 | |

| 2,322,000 | |

| 2,288,100 | |

| 1,227,623 | |

| 936,000 | |

| 520,500 | |

| 507,600 | |

| ~450,000 | |

| 253,899 | |

| 156,600 | |

| 60,000–100,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Shamanism and Animism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Samoyedic peoples | |

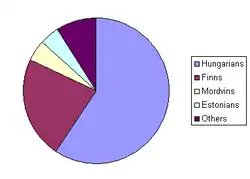

The four most numerous Finno-Ugric peoples are the Hungarians (13–14 million), Finns (6–7 million), Estonians (1.1 million) and Mordvins (744,000). The first three of these inhabit independent states – Hungary, Finland, and Estonia – whereas Mordovia is a republic within Russia.

Other Finno-Ugric peoples have autonomous republics within Russia: Karelians (Republic of Karelia), Komi (Komi Republic), Udmurts (Udmurt Republic), Mari (Mari El Republic), and Mordvins (Moksha and Erzya; Republic of Mordovia). The Khanty and Mansi peoples live in Khanty–Mansi Autonomous Okrug of Russia. The Komi subgroup Komi-Permyaks used to live in Komi-Permyak Autonomous Okrug, but today this area is a territory with special status within Perm Krai.

The traditional area of the indigenous Sami people is in Northern Fenno-Scandinavia and the Kola Peninsula in Northwest Russia and is known as Sápmi.

Peoples

Geographic distribution

Ethnic groups

Ethnic groups with extinct languages

International Finno-Ugric societies

In the Finno-Ugric countries of Finland, Estonia and Hungary that find themselves surrounded by speakers of unrelated tongues, language origins and language history have long been relevant to national identity.[3] In 1992, the 1st World Congress of Finno-Ugric Peoples was organized in Syktyvkar in the Komi Republic in Russia, the 2nd World Congress in 1996 in Budapest in Hungary, the 3rd Congress in 2000 in Helsinki in Finland, the 4th Congress in 2004 in Tallinn in Estonia, the 5th Congress in 2008 in Khanty-Mansyisk in Russia, and the 6th Congress in 2012 in Siófok in Hungary.[4][5][6][7] The members of the Finno-Ugric Peoples' Consultative Committee include: the Erzyas, Estonians, Finns, Hungarians, Ingrian Finns, Ingrians, Karelians, Khants, Komis, Mansis, Maris, Mokshas, Nenetses, Permian Komis, Saamis, Tver Karelians, Udmurts, Vepsians; Observers: Livonians, Setos.[8][9]

In 2007, the 1st Festival of the Finno-Ugric Peoples was hosted by President Vladimir Putin of Russia, and visited by Finnish President, Tarja Halonen, and Hungarian Prime Minister, Ferenc Gyurcsány.[10][11]

Beliefs

Shamanism has had a historically important influence on the mythologies of northern and central Eurasian peoples, including those speaking languages of the Uralic, Yeniseian, Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic language families. Among the Finno-Ugric peoples, though also in Indo-European and North American mythology, are found myths about a world tree or axis mundi, capped by the North Star, at the center of the world, which is encircled by a stream, the idea that asterisms were animal spirits, the idea that the land of the dead beneath the earth was also the home of spirits, and the earth-diver: a bird floating on the primary ocean that dives to bring up the land.[12][13]

Population genetics

A study of Population Genetics of Finno-Ugric speaking humans in North Eurasia carried out between 2002–2008 in the Department of Forensic Medicine at the University of Helsinki showed that most of the Finno-Ugric speaking populations possess an amalgamation of West and East Eurasian gene pools, genetic drift, and recurrent founder effects. North Eurasian Finno-Ugric-speaking populations were found to be genetically a heterogeneous group showing lower haplotype diversities compared to more southern populations. North Eurasian Finno-Ugric-speaking populations possess unique genetic features due to complex genetic changes shaped by molecular and population genetics and adaptation to the areas of Boreal and Arctic North Eurasia.[14]

The proposal of a Finno-Ugric language family has led to the postulation not just of an ancient Proto–Finno-Ugric people, but that the modern Finno-Ugric–speaking peoples are genetically related.[15] Such hypotheses are based on the assumption that heredity can be traced though linguistic relatedness.[16] However, Finno-Ugric has not been reconstructed linguistically; attempts to do so have been indistinguishable from Proto-Uralic.[17]

Like in any other human population, individual groups within the Finno-Ugric language family have a diverse array of cultural, environmental, and genetic influences. However, modern genetic studies have shown that the Y-chromosome haplogroup N3, and sometimes N2, having branched from haplogroup N, which, itself, probably spread north, then west and east from Northern China about 12,000–14,000 years ago from father haplogroup NO (haplogroup O being the most common Y-chromosome haplogroup in Southeast Asia), is almost a specific trait, though certainly not restricted, to Uralic- or Finno-Ugric-speaking populations, especially as high frequency or primary paternal haplogroup.[18]

A recent study has found that haplogroup NO of the Finno-Ugric peoples and their descendants probably spread north, then west and east from Northern China about 12,000–14,000 years ago from its father lineage and today is found in Eastern Europe. The Department of Forensic Medicine at the University of Helsinki showed that most of the Finno-Ugric speaking populations possess an amalgamation of West and East Eurasian gene pools, supporting the idea of mixed origins in these modern populations.

R1a1a7-M458 R1a1a7-M458 frequency peaks among Slavic and Finno-Ugric (maximum - Karelians, maximum among R1a - Komi) peoples.[19]

Archaeology

See also

References and notes

- Korhonen, Mikko: Uralin tällä ja tuolla puolen. In the book Laakso, Johanna (edit.): Uralilaiset kansat, p. 23.

- Demoskop Weekly No 543-544 Archived October 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "A Paradigm Shift in Finnish Linguistic Prehistory". Merlijn de Smit. ButterfliesandWheels.com. 2003. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- "7th World Congress of the Finno-Ugric Peoples". World Congress of the Finno-Ugric Peoples. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "Statutes of the Consultative Committee of Finno-Ugrian peoples". Finno-Ugric Peoples' Consultative Committee. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- "The Congress of the Finno-Ugric Peoples". Russia. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "Fenno-Ugria". Estonia. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "Finno-Ugric Peoples' Consultative Committee, Members". World Congresses of the Finno-Ugric Peoples. Finno-Ugric Peoples' Consultative Committee. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura (in Finnish)". Finno-Ugrian Society (in English). Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "International Festival of the Finno-Ugric Peoples". Press Release from the Kremlin in Russia. 19 July 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "Press Statements by President Vladimir Putin, leaders of Finland and Hungary". Press Release from the Kremlin in Russia. July 19, 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Leeming, David Adams (2003), "The Finno-Ugrians", From Olympus to Camelot, Oxford University Press, pp. 134–137, ISBN 978-0-19-514361-4

- Vladimir Napolskikh. Earth-Diver Myth (А812) in northern Eurasia and North America: twenty years later

- Pimenoff, Ville (2008). "Living on the edge : Population genetics of Finno-Ugric-speaking humans in North Eurasia". University of Helsinki, Finland. Retrieved 12 April 2019.PhD thesis

- Gyarmathi, Sámuel (1 January 1983). Grammatical Proof of the Affinity of the Hungarian Language with Languages of Fennic Origin. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-0976-4.

- "FAQ about Finno-Ugricn Languages". Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "Problems in the Taxonomy of the Uralic languages in the Light of Modern Comparative Studies". Salminen, Tapani. 2002.

- "Article Abstract: A counter-clockwise northern route of the Y-chromosome haplogroup N from Southeast Asia towards Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "Separating the post-Glacial Coancestry of European and Asian Y Chromosomes Within haplogroup R1a". Nature.com. European Journal of Human Genetics. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

Further reading

- Mile Nedeljković, Leksikon naroda sveta, Beograd, 2001.

- People of Volga and Uralic regions. Komi-Zyrians. Komi-Permyaks. Mari. Mordvins. Udmurts. Moscow, 2000. (Russian: Народы Поволжья и Приуралья. Коми-зыряне. Коми-пермяки. Марийцы. Мордва. Удмурты. М., 2000.)

- Petrukhin, Vladimir. Myths of Finno-Ugric Peoples. Moscow, 2005. 463 p. (Russian: Петрухин В. Я. Мифы финно-угров. М., 2005. 463 с.)

- World Outlook of Finno-Ugric People. Moscow, 1990. (Russian: Мировоззрение финно-угорских народов. М., 1990.)

- "Early contacts (4000 BC – 1000AD) between Indo-European and Uralic speakers". Riho Grünthal, Volker Heyd, Mika Lavento, Johanna Nichols & Janne Saarikivi with the help of Satu Keinänen. Editing and layout by Bianca Preda. University of Helsinki.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Finno-Ugric peoples. |

- URALIC PEOPLES

- MORDVINS (Erzyas and Mokshas)

- MARIS or Cheremisses

- VEPSIANS

- The Information Center of Finno-Ugric Peoples (SURI)

- The Information Center of Finno-Ugric Peoples (SURI) Newsletter: "Uralic Contacts"

- Kindred Peoples Programme

- Etnofotu (Ethnofuturism)

- The International Congress of Finno-Ugric Writers

- The Youth Association of Finno-Ugric Peoples (MAFUN)

- International Expedition for high school, college and university students of the Finno-Ugric World

- Finno-Ugric Student's Seminar Camp

- Mari Association of Finno-Ugric Peoples

- Federal Finno-Ugric Cultural Center (Sykytyvkar, Komi Republic)

- Article on plans for new Federal Finno-Ugric Cultural Center in Sykytyvkar, Komi Republic

- International Finno-Ugric Students' Conference (IFUSCO)

- The International Festival of Theatres of Finno-Ugric Peoples

- World Championship of Kalevala Chanting & Ugric Rumble Ethno Music Festival

- Uralkult Festival: "Finno-Ugric culture now!"

- Ugriculture: Contemporary Finno-Ugric art at the Gallen Kallela Museum

- On the Banks of the Volga: "Life of a Finno-Ugrian people past and present"

- Bearslaying Theatre Festival: Theatre by Finno-Ugric Peoples

- Indiana University Bloomington |Central Eurasian Studies: Uralic Peoples

- Finno-Ugric media center