French Gothic stained glass windows

French Gothic stained glass windows were an important feature of French Gothic architecture, particularly cathedrals and churches built between the 12th century and 16th century. While stained glass had been used in French churches in the Romanesque period, the Gothic windows were much larger, eventually filling entire walls. They were particularly important in the High Gothic cathedrals, most famously in Chartres Cathedral. Their function was to fill the interior with a mystical colored light, representing the Holy Spirit, and also to illustrate the stories of the Bible for the large majority of the congregation who could not read.[1]

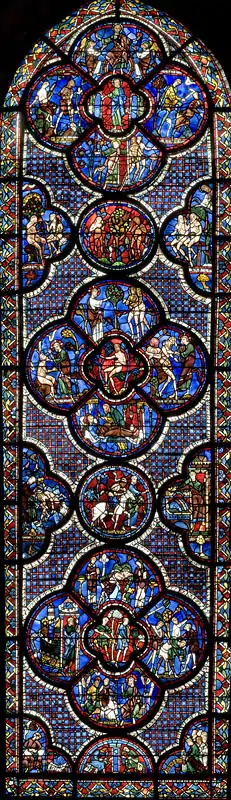

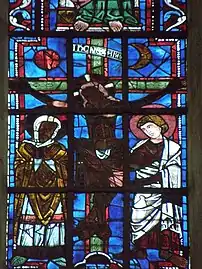

The Good Samaritan Window from Chartres Cathedral | |

| Years active | 12th to 15th century |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

The rose window was a particularly important feature of the major French cathedrals, beginning with Notre Dame de Paris. It was usually found over the portals on the west front, and frequently also on the transepts.

Over the years of the Gothic period, the windows became larger and larger, allowing in more light through grisaille glass, and the details on the painted glass became much finer, gradually resembling paintings. A large part of the original glass was destroyed in the centuries after the Middle Ages; much of the glass today is restored or a more modern replacement.[1]

Early Gothic (12th – early 13th centuries)

Basilica of Saint Denis

Basilica of Saint-Denis, Apse, axial chapel, The Annonciation, with Abbot Suger, the patron, depicted at the feet of the Virgin. (1140–1144)

Basilica of Saint-Denis, Apse, axial chapel, The Annonciation, with Abbot Suger, the patron, depicted at the feet of the Virgin. (1140–1144) Windows of the Chapel of the Virgin at the Basilica of Saint-Denis. The Tree of Jesse window is on the right

Windows of the Chapel of the Virgin at the Basilica of Saint-Denis. The Tree of Jesse window is on the right Detail of the Tree of Jesse window, Baslica of Saint-Denis (1140–44)

Detail of the Tree of Jesse window, Baslica of Saint-Denis (1140–44)

Only a very small amount of original 12th-century French stained glass remains. Much of it was destroyed, and replaced in the 19th century. The early windows were assemblages of very small pieces of glass, often of different thicknesses, often painted, which could only be seen from a distance. Their principal effect was their characteristic of constantly changing, depending upon the exterior light of the moment.[2]

The first important Gothic structure in France was the royal Basilica of Saint Denis (now the Cathedral of Saint Denis), the traditional sepulchre of the French Kings located just outside Paris. The Abbot Suger, a close advisor of the French King, who directed the government during the King's absence during the Crusades, rebuilt the ambulatory with Gothic rib vaults primarily to create greater space for stained glass windows.

The medieval French church, Following the doctrine of Saint Augustine, associated light with the power of God, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Suger was an admirer of the doctrines of the early Christian philosopher John Scotus Eriugena (c. 810–87) and Dionysus, or the Pseudo-Areopagite, who taught that light was a divine manifestation, and that all things were "material lights", reflecting the infinite light of God himself.[3] For Suger, stained glass became a way to create a glowing, unworldly light ideal for religious reflection.[4] Suger described the finished work at Saint-Denis as "a circular string of chapels, by virtue of which the whole church would shine with the wonderful and uninterrupted light of most luminous windows, pervading the interior beauty".[3] This continued to be the guiding reason for stained glass windows throughout the Gothic period. Pierre de Roissy, a dignitary of the Chapter of Chartres Cathedral, wrote in about 1200 that the stained glass windows being installed in the nave "would transmit the clarity of the sunlight, signifying the Holy Scriptures, which push evil away from us, as they illuminate us."[2]

One window at Saint-Denis illustrated the patron himself, Abbot Suger, at the feet of the Virgin Mary. The Abbey also had a Tree of Jessé window, depicting the genealogy of Christ, which became a common feature at Gothic cathedrals for the next century.

The early Gothic windows each had a theme or subject, such as "The Passion of Christ", illustrated by dozens of individual medallions. In tall lancet windows, there were one or two medallions on each level, three at the most. each no larger than a square meter. The circular medallions were separated by wide borders with geometric or floral decoration. The story of the window could be read from medallion to medallion, usually from the bottom to the top. The subject matter was not chosen by the artist, but by the ecclesiastical authorities of the cathedral. They illustrated the lives of the Saints and Christian martyrs, and the episodes of the New and Old Testament, for the large part of the congregation which could not read. Many windows included panels illustrating the work of the guild, such as the masons or bakers, which had financed them.[2]

Chartres Cathedral early period (12th c.)

Top of the Tree of Jessé Window, Chartres Cathedral (1150)

Top of the Tree of Jessé Window, Chartres Cathedral (1150) Detail of the stained glass window called Notre-Dame de la Belle Verierre

Detail of the stained glass window called Notre-Dame de la Belle Verierre Chartres Cathedral, Passion of Christ windows, (c. 1150)

Chartres Cathedral, Passion of Christ windows, (c. 1150)

A few important examples of 12th-century windows are found at Chartres Cathedral on the inside of the western facade, in three lancet windows under the rose window. These windows survived a devastating fire in the Cathedral in 1194, and are considered some of the best examples of 12th-century work in France.[5] They introduced the famous Chartres blue, glass colored with Cobalt(II) oxide, which cooled and balanced the vivid reds and yellows of the windows. Each of the windows also contains a medallion which illustrates its donors; the butchers for the Miracle of the Virgin Window, the water-carriers for the Story of Mary Magdalene window. The cathedral also has an early Tree of Jessé window, illustrating the genealogy of Christ in the shape of a family tree imagined in a dream by the prophet Jesse.[5]

High Gothic and Rayonnant (13th century)

The development of the rib vault and the flying buttress resulted in cathedrals that were higher and higher, with less need for thick walls and greater space for windows. The intermediate levels of the walls, occupied by galleries during the Romanesque period, were merged and given windows. As a result, the upper walls between the buttresses were gradually filled with larger and larger windows.[6]

The changes in architecture were accompanied by technical and artistic innovations in the making of the stained glass. The small early Gothic windows with their deep, rich colors were replaced by much larger and thinner windows that allowed in more light. They had simpler, more geometric designs and the figures more expressive faces, that could be visible from far below. The space around the figures was often left white or in grisaille, or decorated with vegetal or floral designs. Pale yellows and ochres, made with Silver stain (which gives the name to "stained glass"), became more common. and colors were more nuanced.[7]

Chartres Cathedral later period (13th century)

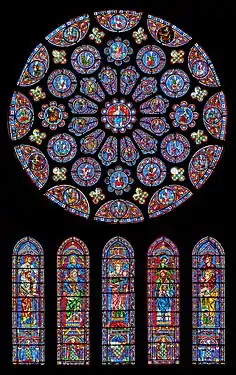

West rose window and lancets, Chartres Cathedral

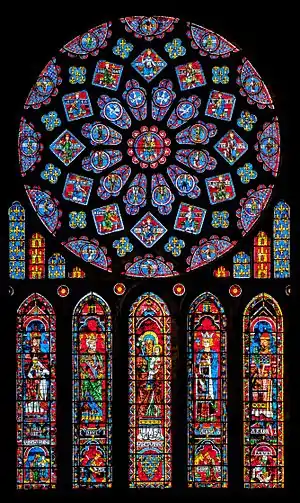

West rose window and lancets, Chartres Cathedral South rose window, Chartres Cathedral (1221–1230)

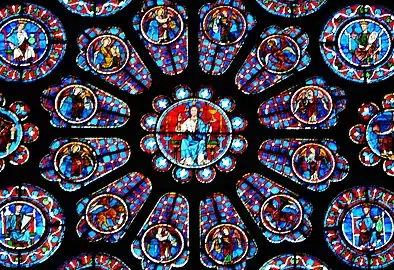

South rose window, Chartres Cathedral (1221–1230) Detail of the south rose window, Chartres

Detail of the south rose window, Chartres Chartres north rose window

Chartres north rose window

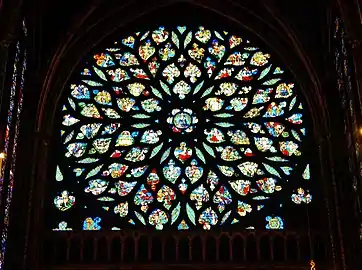

Following the destruction of a large portion of the Cathedral in 1194, a major fund-raising campaign began to rebuild it. The King of France contributed, as did his English enemy, Richard the Lion-Hearted. So did the merchants and guilds of Chartres, who sponsored new windows. The new cathedral was almost finished in the remarkably short time of twenty-five years, though it was not re-consecrated until 1260. As a result, the stained glass has a remarkable unity of style, exemplified by the windows of the nave, and particularly by the north and south rose windows, with their delicate balance of reds and blues.[5] In Chartres, thanks to the additional support provided by the new flying buttresses, the walls were made into a series of bays, each with a small rose window above and two lancet windows below.[8] Over the coming years in other cathedrals, such as Amiens in 1220, the space between the windows in each bay was gradually reduced until the windows occupied much of the wall.[8] The rebuilding also included the creation of two large new rose windows in the transepts. After reconstruction, Chartres had one hundred sixty windows and three rose windows, making the windows a dominant feature of the architecture. So many windows were created for new cathedrals in the early 12th century that multiple workshops, in different styles, were sometimes employed on the same Cathedral. Three different workshops were at work at Bourges Cathedral between 1210 and 1215. This marked the beginning of the High Gothic, or "Classique" style of French Gothic architecture and stained glass.[8]

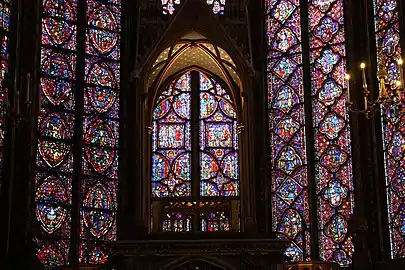

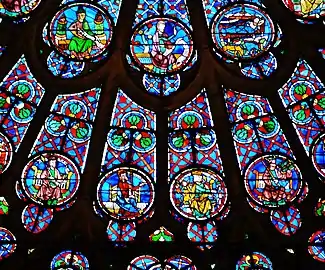

Rayonnant Gothic - Sainte-Chapelle

Devil kidnapping a woman, Sainte-Chapelle pane (mid-13th c.) (Now in Museum of Middle Ages, Paris)

Devil kidnapping a woman, Sainte-Chapelle pane (mid-13th c.) (Now in Museum of Middle Ages, Paris) Upper windows

Upper windows Detail of South Bay window; the King

Detail of South Bay window; the King

Between about 1225–1230, a new style began to appear in the Ile-de-France and other regions, which was seen in architecture, sculpture and painting as well as stained glass. It was more graphic, more summary, with simplified forms, presented rigid stylisation of faces while the robes and clothing became more realistic. Historians later gave the period the name Rayonnant. Important early examples include the west rose window of Notre Dame de Paris, the chapel of the Virgin of the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Pres (destroyed in the 18th century, but some of the glass was preserved).[9]

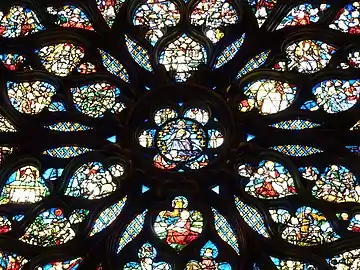

The most important and influential work in this style is the upper royal chapel of Sainte-Chapelle (1234–1244), built for Louis IX to display his recently acquired collection of sacred relics.[10] The single chapel contains 670 square meters of stained glass, not counting the later west rose window, and the walls, 20.4 meters high under the vault, appear entirely to made of glass. This was made possible by moving the supports of the wall, clusters of nine colonettes, to the exterior. In addition, the windows were supported by two series of iron bars, at mid-height and at the summit. The iron support bars are concealed by the bars of the tracery. Other metal supports for the windows are hidden under the eaves of the roof.[11]

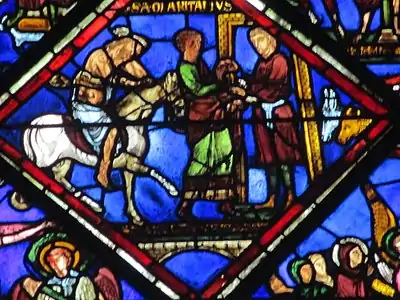

The iron bars of the window tracery formed trilobs, quadrilles, medallions, and other geometric shapes framing each scene. Because of this complex network, of frames, each panel was very small; the figures at the upper levels are nearly impossible to discern. The important figures and scenes are placed in additional quadrilateral settings of mosaic-like decoration, dominated by red and blue colors. Similar red-blue quadrilateral designs set off the images of heraldic shields, images of the castles of Castille, and especially the royal emblems, the Fleurs-des-Lis.[12]

The upper chapel has fifteen windows, composed of 1,113 panels of glass. Nearly two-thirds of the glass is original.[11]

Unlike the windows of most Gothic cathedrals, where the windows were primarily devoted to the lives of the Saints and Apostles, the windows of Sainte-Chapelle were primarily devoted to the relics preserved in the chapel; fragments believed to be from the True Cross and the Crown of Thorns from the Crucifixion of Christ. The windows depicted the history of the Hebrew people, and finally connected the Biblical Kings with the reign of the window's patron, Louis IX. The King was depicted in the windows carrying the crown of Christ.[13]

The windows of Sainte-Chapelle are believed to have been made by three different workshops, with slightly different styles.[13] Some seem to have been influenced by new developments in illuminated manuscripts. The designs of the glass displayed rich decoration, an elegance of figures and a precision of gestures not seen before in stained glass.[9][13]

The Sainte-Chapelle window styles found an immediate echo in the windows of other 13th century cathedrals and churches, notably Soissons Cathedral, made shortly after Sainte-Chapelle, likely by the same artists.[14]

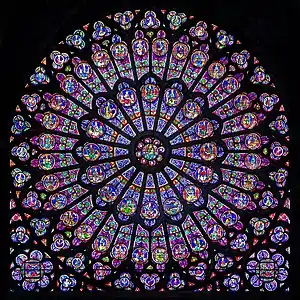

Notre Dame de Paris

North rose window of Notre Dame de Paris (about 1250)

North rose window of Notre Dame de Paris (about 1250) Detail of the south rose window

Detail of the south rose window Detail of window from St. George's chapel, Notre Dame de Paris (13th c.)

Detail of window from St. George's chapel, Notre Dame de Paris (13th c.)

Other major examples of Rayonnant stained glass are the great north and south rose windows of the transept of Notre-Dame de Paris, whose construction was sponsored by King Louis IX of France.

Saint-Denis

Another influential group of rayonnant windows was created for the Basilica of Saint-Denis by Suger's successor, the Abbot Eudes Clement. He preserved the original windows in the disambulatory, but reconstructed the central sanctuary and built a large new transept to replace the Carolingian nave. The new nave and transept had two important innovations. First, the traditional piers that supported the roof were replaced by pillars that grouped together colonettes. These collonettes connected directly with the pained arches of the vaults. Second, as a result, the pointed arches of the windows could entirely fill the upper wall. Two very large rose window entirely filled the upper ends of the north and south transepts. The rebuilt abbey was consecrated in 1281. The design of the Sant-Denis window, created by the radiating stone mullions, later gave the new style its name, "Rayonnant".[15]

Northern and western France

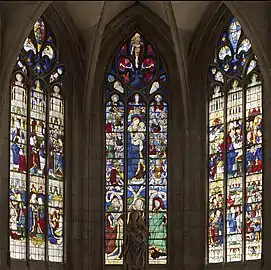

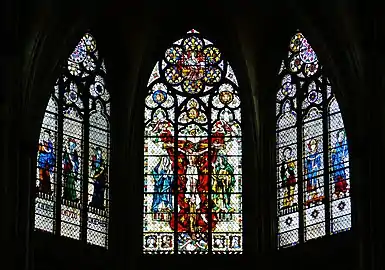

_Basilique_Saint-Urbain_Vitrail_de_la_Crucifixion.jpg.webp) Windows of Basilique Saint-Urbain de Troyes

Windows of Basilique Saint-Urbain de Troyes West window of Troyes Cathedral

West window of Troyes Cathedral Windows of Troyes Cathedral About 1270)

Windows of Troyes Cathedral About 1270) Crucifixion, Chalons Cathedral in Champagne 1230–1237)

Crucifixion, Chalons Cathedral in Champagne 1230–1237) The Good Samaritain, Sens Cathedral (13th century)

The Good Samaritain, Sens Cathedral (13th century)

The Cathedrals of Amiens, Troyes, Reims and Chalons-sur-Marne in northern France were among the first to adopt the new Rayonnant window styles, alongside windows in the earlier 1200 style. The new windows of Troyes Cathedral in the Champagne region featured intense colors.[16] The figures in the windows of the Cathedral of Chalons-sur-Marne (1240–45) detached themselves from the unified background. The windows of Reims Cathedral (1240–45) depicted the apostles atop edicules depicting the churches and bishops of Champagne.[17]

In western France, the change in style came later, not beginning until 1245–1250. At Le Mans Cathedral, the windows became more geometric, and the figures were reduced in size. Between 1255 and 1260 another new tendency appeared in French windows; large panels surrounding the colored figures were filled with grisaille, or grey or white glass. In the south, in Clermont-Ferrand, window-makers continued to used small panes of glass of a single color, while in other cathedrals, such as Tours Cathedral, multiple colors appeared in the same pane. Gradually, most new churches began to follow a uniform theme; the upper windows of the choir used solid colors, with the exception of the windows over the choir, whee the figures were surrounded by grisaille.[18]

Throughout France, The figures also evolved toward the style of mannerism. During the period of 1255–60, The windows began to follow the style used in the royal manuscripts painted after the return from captivity of Louis IX.[18]

In the second part of the 13th century, the grisaille portions were animated by quadrille panes illustrating biblical stories and bordered with delicate foliage. The figures were presented with their heads half-turned, the figures made highly expressive gestures. The new lighter colors and mannerist figures influenced windows beyond France. The Basilique Saint-Urbain de Troyes built by Urban IV beginning in 1262 at his birthplace, was a good example of the new style.[18]

Forty years later, in the 14th century, with the introduction of silver stain in the Ile-de-France and Normandy, the stained glass windows ceased to be mosaics of different colors, and came much closer to paintings, with equal luminosity throughout.[19]

Early Flamboyant style (14th century)

Windows of Tours Cathedral (14th century)

Windows of Tours Cathedral (14th century).JPG.webp) Window of Evreux Cathedral (14th century)

Window of Evreux Cathedral (14th century) Thomas Becket window at Saint-Ouen Abbey, Rouen

Thomas Becket window at Saint-Ouen Abbey, Rouen Detail of the Thomas Becket window, Saint-Ouen Abbey, Rouen, with architectural settings

Detail of the Thomas Becket window, Saint-Ouen Abbey, Rouen, with architectural settings Grisaille windows at Troyes Cathedral

Grisaille windows at Troyes Cathedral 14th century glass in Sens Cathedral

14th century glass in Sens Cathedral

In the Fourteenth century France was engaged in the Hundred Years War with England, and also faced a series of deadly epidemics of the Plague. The royal government, occupied with the war, reduced its patronage of the arts. Nonetheless, creation of stained glass continued, with continuous innovations, particularly of more grisaille to make the windows lighter, and more extensive use of silver stain and painting upon the glass. Much of the innovation took place in Normandy, at Rouen Cathedral and Evreux Cathedral.[20]

The earliest examples of using grisaille in upper windows existing today are from 1260 to 1270, in the high choir of Tours Cathedral, and on the upper level of the Chevet in Troyes cathedral. Other examples appeared in the clerestory windows of Chartres Cathedral. The upper part of the Choir of Chartres was pulled down in 1270 and rebuilt in the new style, with larger windows. The windows were finished by about 1300. Following the new style, a large part of the space surrounding the figures was filled with grisaille.[21] Other signs of the changing style appeared in the nave windows; the richness of colors of the early Chartres windows was still there, but the ornate medallions disappeared, and elaborate canopies and arches, similar to the architecture of the church, were placed over the figures to highlight them. This became a common characteristic of the flamboyant. Each vertical section of window usually contained two tall figures, one over the other, surrounded by grisaille.[21]

At Evreux Cathedral, whose windows date from the whole span of the 14th century, the figures often include small colored panels showing the donors of the windows with their patron saints. The decoration is largely made up of heraldry and variations of the fleur-de-lis design.[21] Other early examples appear at the Saint-Ouen Abbey, Rouen, which has one of the best collections of 14th-century glass in France. Its windows include the Thomas Becket window, illustrating the martyrdom of that Saint. Like other windows of the period, much of the window is grisaille, allowing in a maximum of light, while the figures are framed by elaborate architectural detail, matching the ornate architecture of the church itself. The Flamboyant windows gradually abandoned mosaic-like appearance of the early stained glass windows, and came more and more to resemble paintings.[21]

One distinctive feature of the flamboyant was a curvilinear design of the stone mullions within the arched top of windows which, with some imagination, resembled flames agitated by the wind. This design gave the style its name, flamboyant. It had two components; the upper element, called the soufflet, which resembled an elongated four-leaf clover; which was flanked by two mouchettes, undulating spindle-shaped forms decorated with cusps in designs. Variations of this design were found at the top of many flamboyant windows.[22]

The use of a light-coloured grisaille, and then a white background, became more and more common in the 14th century. Windows became more refined and had a broader range of colors. The walls of the cathedral interior were increasingly covered with dense tracery and decoration, competing with the windows. The figures in the windows were often surrounded by white glass to frame them and make them stand out. Superimposed medallions, in a form called "Legendaire", became a common feature. Lancet windows became another common feature of the windows. Instead of having multiple figures, lancet windows had only a single figure, surrounded by white.

The quality of the glass became much better in the fourteenth century, due to improvements in the materials and the process of glass-blowing. The white glass became lighter and more translucent.

A new technique was introduced, adding a thin layer of colored enamel paint to the outside of the windows. This could be delicately scraped with a stone instrument to give relief and variation to the color. The process of silver staining also was developed. The outside of the glass would have coloring of silver stain, while the artist painted the figures on the inside. The artist could employ several different colors and shades on a single pane of glass.[20]

The techniques of painting on the glass also improved. Figures became more realistic and more refined, as the artists followed the style of the illuminators of manuscripts.[23]

A new phase, called International Gothic, appeared in Europe in about 1360, as styles and innovations were shared between countries. One source of new ideas in France was the court of the Popes in Avignon, installed in 1309. The court helped introduce Renaissance artistic ideas such as realism and perspective into French art, including stained glass.[23]

Another important change to French stained glass took place in the 14th century. This was a change in the narrative style of the window. Prior to the 13th century, windows were of dozens of scenes from the life of a Saint or martyr, showing all the episodes of his life. In the 14th century, windows began to concentrate on one single important event of the martyr's life at a larger scale. Another innovation of the 14th century was the use of a medallion illustrating the donor of the window. Some donors had several medallions dedicated to them, and one, Raoul de Ferrieres, had an entire lancet window at Evreux Cathedral dedicated to him.[23]

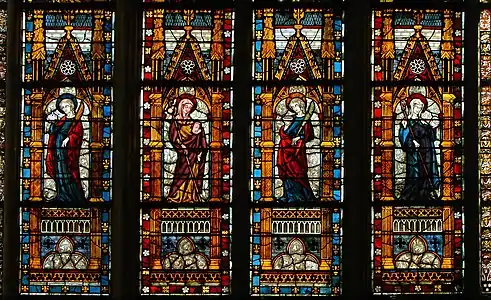

Later Flamboyant (15th century)

Window of Saint-Séverin Paris (15th century)

Window of Saint-Séverin Paris (15th century) Joseph and his brothers, Saint-Chapelle (15th century)

Joseph and his brothers, Saint-Chapelle (15th century) Rose window of Sainte-Chapelle (1485–98)

Rose window of Sainte-Chapelle (1485–98) Detail of the rose window of Sainte-Chapelle - the Apocalypse (1485–98)

Detail of the rose window of Sainte-Chapelle - the Apocalypse (1485–98)_-_Vision_of_7_candlesticks.jpg.webp) Drawing of Center of the rose window of Sainte-Chapelle – vision of the Seven Candlesticks (c. 1485) (see photo at left)

Drawing of Center of the rose window of Sainte-Chapelle – vision of the Seven Candlesticks (c. 1485) (see photo at left) Apse chapel of Evreux Cathedral (restored after World War II)

Apse chapel of Evreux Cathedral (restored after World War II) Detail of Evreux Cathedral window (15th c., restored)

Detail of Evreux Cathedral window (15th c., restored) Rose window of Church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen

Rose window of Church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen Flamboyant windows of the nave of the royal abbey-church of Saint-Ouen, Rouen (early 16th c.)

Flamboyant windows of the nave of the royal abbey-church of Saint-Ouen, Rouen (early 16th c.)

In the early 15th century, very little new stained glass was made in France; the country was in the midst of the Hundred Years war, preoccupied the disastrous defeat at Agincourt, the conquest of France by Henry V of England, and the liberation by Joan of Arc. Not until the English were expelled did French architecture regain its important position.[24]

In the second half of the 15th century, the art of stained glass revived dramatically in France, and approached closer and closer to that of painting, with the use of perspective and other painterly techniques. But before long France gradually lost its dominance, as International Gothic style, particularly in Germany and Flanders rose in prominence. The work of the Flemish Van Eyck brothers became the inspiration for windows across Europe.[25]

The general characteristics of French stained glass in this period include whole panels filled with decorative canopy work, almost all in white, with just touches of stain. The canopy designs were intricate patterns of line and form to accompany the intricate details of the Flamboyant interiors. An important innovation was the borrowing of methods of early Renaissance painting. In some cases the figures of the windows completely crossed the dividing mullions, occupying more than one panel of glass.[26]

In the 15th century, the names of stained glass artists became known, and artists began to travel from city to city to make windows. Stained glass workshops were located in the major European cities, and began to dedicate more and more of their time to the maintenance of existing windows. The makers of stained glass were declared exempt from taxes at the end of the 15th century by King Charles V of France.[25] Stained glass artists also began to have a wider variety of clients; not only kings but also wealthy aristocrats and merchants. Windows were made not only for cathedrals but also for town halls and palatial residences. The Duc Jean de Berry, brother of King Charles V, commissioned stained glass windows for his residence in Bourges. As paper became more common, drawings of prominent windows circulated around Europe, and the same design could be used in several different cities.[25]

Important windows made in France during this period include the rose window on the west facade of Sainte-Chapelle (1485–98), which used paint on glass with exceptional realism and fantasy to depict the Apocalypse. the Church of Saint Severin in Paris is another example.[25] Rouen was an important center for making late Gothic glass; an exceptional collection of windows from this period is found at the Church of Saint-Maclou in Rouen.[27]

Bourges Cathedral

Bourges Cathedral, window of the Apostles (15th century)

Bourges Cathedral, window of the Apostles (15th century) Bourges Cathedral, Scenes from the life of Saint Denis (15th century)

Bourges Cathedral, Scenes from the life of Saint Denis (15th century) Bourges Cathedral, Chapel of Jacques Coeur, The Announciation (1448–1450)

Bourges Cathedral, Chapel of Jacques Coeur, The Announciation (1448–1450)

Bourges, under The Duke Jean du Berry, the brother of King Charles V of France, was a major center for stained glass in the 15th century. It had its own Sainte-Chapelle, which was destroyed in the French Revolution. A few of the windows survived and were reinstalled in Bourges Cathedral in the 19th century. Following the style of the 15th century, the windows frequently portrayed the figures of saints and patrons against a dark background, while the higher parts of the windows were filled with very elaborate arches and other architectural features, usually in white, which fit with the interior decoration of the church.

Transition to Renaissance (16th century)

16th-century windows in Nave at Troyes Cathedral

16th-century windows in Nave at Troyes Cathedral 16th-century windows at Troyes Cathedral

16th-century windows at Troyes Cathedral 16th-century window in church Saint-Pierre de Dreux

16th-century window in church Saint-Pierre de Dreux

Patrons

Windows were very expensive to make, and most cathedral windows were financed by donors, ranging from Kings and nobles to the craftsmen of the guilds of the city. King Louis IX directly financed the rose windows at Notre-Dame de Paris and all of the windows at Sainte-Chapelle, which are filled with symbols of his reign.

The first stained glass window to portray its patron is at the Basilica of Saint Denis, where an image of the Abbot Suger is shown at the feet of Christ. But later in the 12th and 13th centuries, the practice became very common. The patrons were frequently pictured in the windows that they funded, either praying or, in the case of the craft guilds, shown at work. Windows depicted bakers, butchers, tanners, furriers, money-changers, and other professions at work.[21] The rose window of the south transept of Chartres Cathedral contains the coats of arms of its patron, Peter I, Duke of Brittany, in the trefoil of the rose and the central lancet, along with portraits of his wife and his son and daughter, kneeling.[21]

Peter I, Duke of Brittany, patron of the south rose window of Chartres Cathedral, portrayed in the window.

Peter I, Duke of Brittany, patron of the south rose window of Chartres Cathedral, portrayed in the window..JPG.webp) Patrons of a window at Évreux Cathedral

Patrons of a window at Évreux Cathedral Cloth workers, patrons of a window at the Collegiate church of Semur-en-Auxois (about 1460)

Cloth workers, patrons of a window at the Collegiate church of Semur-en-Auxois (about 1460) Shoemakers, among the patrons of the Good Samaritan window of Chartres Cathedral

Shoemakers, among the patrons of the Good Samaritan window of Chartres Cathedral

Symbolism

The cathedral was intended to represent the Kingdom of Heaven on earth, and every element of the stained glass was rich with Christian symbolism.[28] The walls of glass corresponded with the walls of the celestial city, ornamented with jewels and filled with divine light, as it was described in the Book of Revelation. The scenes within the windows were full of symbols. A panel of workers with a background or frame of elaborate arches and columns indicated that they were not in an ordinary workshop, but laboring in a celestial workshop. Even the decorative elements had a meaning. The climbing ivy which surrounded many of the scenes represented the renewal of the Garden of Eden on earth.[28]

The Apostles and Saints were generally portrayed with objects associated with them, so viewers could recognise them, in the same fashion as Gothic sculptures. A female figure with a crown represented the Church. A seraphim or angel putting away a sword represented either the Angel who guards the gates of paradise, or the peace made between God and man by the atonement of the Crucifixion.[29]

Technique

Making the glass

The technique of making stained glass windows in the early Gothic was essentially the same as in the Romanesque period. The glass was made at a separate site, usually near a forest, where abundant firewood for melting the glass was available. One variety of the process was described in detail at the beginning of the 12th century by the monk Theophile in a tract called "Schedula Diversarum Artium" or "Treatise on the Diverse Arts".[30]

In the technique described by Theophile, called "By Manchon", the ingredients, a mixture of two-thirds vegetal ashes, which provided potassium, was combined with a third of river sand, which provided silicon. This method was most commonly used for making bottles and glasses. The glass was blown at the end of a tube into a spherical bubble, which while hot was rolled into a cylinder shape. While it was still hot, the ends were then cut off the cylinder, and it was flattened with a wooden spatula into a flat rectangle.[30]

The French used a variation of this plan, called "Plateau" or "Cive" glass. In this method, the glass was first blown into a bubble as in the preceding method. Then, while the bubble was still hot, a second tube was inserted at the other end of the bubble, and the first tube was detached. The glass was continually rotated and gradually pushed and flattened into a circular disk or plate, with a slight rise in the center where the tube had been inserted.[30]

The colors were created by adding metal oxides; usually iron oxide, copper and manganese, to the molten glass. Cobalt created the famous blue of the Chartres windows. Copper could make a yellow, a green or a blue. Red was the most difficult color to make, since the red coloring let very little light pass through. In this case, the hot blown glass was dipped into vessel containing red colorant, which fused to the glass.[30]

Near the end of the 13th century, glass makers began to add layers of different colors to the glass, which could then be ground or engraved away to achieve more varied shades and combinations of color. Gradually the glass colors became more and more like the colors used in painting.[31]

Making the window

The first step in making the window was the design, a colored drawing about one-tenth of full size, made for the approval of the master builder and the patron of the windows. This plan showed the design of the lead and iron framework that held the glass together, and the colors of each piece. The peintre verrier, or glass painter, selected the colors, choosing from small sample colored pieces provided by the glassmaker. Once the plan was approved, An exact copy of the plan, in full size, was drawn in charcoal on the top of a large table covered with plaster. The position and color of each piece was noted and numbered.[12][31]

Copies of each section of the window, showing each piece of glass, were carefully traced and given to the terrier, or glassmaker. He carefully cracked off the pieces he needed from larger pieces of colored glass, using a heated iron tool in the early period, and a diamond cutter in the later period.

Painting the window

Painted details of Sampson and the lion, from Sainte-Chapelle (now in the National Museum of the Middle Ages, Paris

Painted details of Sampson and the lion, from Sainte-Chapelle (now in the National Museum of the Middle Ages, Paris

The painter would add details of clothing and faces and other details. The "paint" in early Gothic was an enamel, a mixture of iron oxide or copper oxide powder with water and gum arabic that made a dark brown or grey. It was more or less diluted to vary its transparency.[12] The color was mixed with "soft" glass, a kind of glass with a low melting point, which would allow the mixture to be fused directly with the glass of the windows.[21]

The painters placed the window section on an open easel placed before a window, or put the glass flat onto a transparent table, so the artist could see the effect of the light coming through the glass. Once the painting of a pane was finished, it was baked at 600 degrees Celsius to fix the color.[32]

In the Flamboyant period, artists developed the use of matt shading, which allowed the creation of shadows and the appearance of three dimensions. This was done by putting a layer of semi-transparent enamel over the whole surface of the glass, and, when it was dry, but before it was fired, using a small stiff hog's hair brush to brush out the graded lights and half-tones. This allowed much greater realism and detail, and moved stained glass art even closer to painting.[21]

Assembly

The pieces were then trimmed, and then fit into the slots of thin lead strips that held them together. Gaps between the glass and lead were filled with resin, and the edges were sealed with wax. The lead strips were soldered together to complete the panel. The window was then placed into the bay of the wall, and secured with iron bars fixed into the masonry.[31][32]

Lead strips and iron bars of Thomas Becket window at Canterbury Cathedral (Late 12th – early 13th c.)

Lead strips and iron bars of Thomas Becket window at Canterbury Cathedral (Late 12th – early 13th c.)

Silver stain

Painted angel colored with silver stain, (14th c.), the Louvre

Painted angel colored with silver stain, (14th c.), the Louvre Glass colored with yellow silver stain surrounds and highlights the figures in a Flamboyant window at Toulouse Cathedral

Glass colored with yellow silver stain surrounds and highlights the figures in a Flamboyant window at Toulouse Cathedral

Beginning in the 1300s, windows were often given additional nuances of color using Silver stain, a mixture of salts of silver ground finely, mixed with yellow ochre, and diluted with water. This was the ingredient the gave rise to the term "stained glass". The stain was applied on the outside face the window, while the details were painted on the inside. Silver stain was used to produce a range of colors from yellow to orange and brown shades. It could produce green, if painted onto blue glass. This made it possible to give greater nuances to colors and shades. Small touches could give a particular brilliance to the window; a gold color in windows was usually created with silver stain.[33]

Silver stain had been used in Egypt as early as the 8th century to color vases, and was adapted by Arab artists and introduced into Spain. It was first used in Normandy in about 1300 and in England in 1310. With the use of silver stain, the windows gradually lost the appearance of a mosaic of colored glass pieces and increasingly looked like illustrations of illuminated manuscripts.[34]

Flashed glass

At the end of the 13th century, window artists also applied additional layers of colored glass to their windows, then engraved the upper layers to reveal the colors beneath. This provided even more subtle and delicate shades, and gradually moved the art of stained glass closer and closer to that of painting. But it also destroyed some of the purity and mystical quality of the earlier stained glass, where the color was provided entirely by light passing through glass.[35]

Color

12th-century glass, the Burning Bush from the Life of Moses, at Basilica of Saint-Denis (12th century)

12th-century glass, the Burning Bush from the Life of Moses, at Basilica of Saint-Denis (12th century) Grisaille and silver stain (used for the gold color) in window from Chartres Cathedral (13th century)

Grisaille and silver stain (used for the gold color) in window from Chartres Cathedral (13th century) Saint-Ouen Abbey, Rouen (completed 15th century) had a full range of colors, set against a white background.

Saint-Ouen Abbey, Rouen (completed 15th century) had a full range of colors, set against a white background.

In the 12th century early Gothic, the dominant colors were a deep and rich blue, and a ruby red. The colors were often uneven and streaky, but the intensity of the color, particularly in the small windows, was greater than in later windows.[21] These colors were used for all of the backgrounds of the figures, and were rarely painted upon. The enamel paints were used mostly for the decoration of white and other paler glass. Only in the early 13th century did the artists begin covering the blue backgrounds with painted designs. White glass was used sparingly, like a thread woven into the design.[21]

In the 13th and 14th centuries, a wider variety of colors and shades became available, through the use of grisaille, silver stain and flashing. The colors were more consistent, but less rich and deep than the early Gothic colors. Part of this resulted from optics; in the dark churches of the 12th century, the colors of the small windows, with their thick glass, and greater contrast and seemed more vivid. In the 13th and 14th centuries, the artists concentrated the colors in the figures, to make them stand out against the light backgrounds.[21]

Tracery

Plate tracery. Early Gothic plate tracery, west rose window of Chartres Cathedral (12th century)

Plate tracery. Early Gothic plate tracery, west rose window of Chartres Cathedral (12th century) Rayonnant north rose window of Notre-Dame de Paris (13th century)

Rayonnant north rose window of Notre-Dame de Paris (13th century) Flamboyant west rose window of Sainte-Chapelle (late 15th century)

Flamboyant west rose window of Sainte-Chapelle (late 15th century)

As the windows became larger and larger, this led to the development of tracery, a network of stone ribs or mullions, reinforced by iron bars, that framed the lights, or sections of glass.[36]

Early Gothic windows were small, and each light was set into a separate opening of the stone wall. This was called Plate tracery, and it was used most famously in the Early Gothic rose window of Chartres Cathedral.[35]

By the end of the 12th century, as the windows became larger, it was necessary to devise a new system to give the glass greater resistance to the wind. Each panel of glass was inserted into a framework, originally of wood, later of iron bars, placed at right angles. An example is the Tree of Jessé window at Saint-Denis (see image above).

The larger rose windows of the 13th century, particularly those of Chartres Cathedral and Notre-Dame de Paris, required a different kind of tracery. The mullions and bars were modified into curvilinear forms, outlining the panels of the glass, creating elaborate designs within the window. The mullions of Notre-Dame de Paris spread outwards from the center like the rays of the sun, giving Rayonnant style its name. In later Gothic the tracery frames, seen from the outside, merged with the tracery decoration of the Cathedral facades.[35]

See also

Notes and citations

- Brisac 1994, p. 7–11.

- Brisac 1994, p. 13.

- Watkin 1986, p. 128.

- Watkin 1986, p. 126–128.

- Houvet 2019, p. 67–68.

- Brisac 1994, p. 34.

- Brisac 1994, p. 33–34.

- Brisac 1994, p. 33.

- Brisac 1994, p. 60–64.

- de Finance 2012, p. 31.

- de Finance 2012, p. 34.

- de Finance 2012, p. 46.

- de Finance 2012, p. 46–48.

- de Finance 2012, p. 48.

- Mignon 2017, p. 125.

- Balcon & Philippot 2001.

- Brisac 1994, p. 66.

- Brisac 1994, p. 66–67.

- Brisac 1994, p. 67.

- Brisac 1994, p. 89.

- Arnold 1913, Chapter XI.

- Ducher 1988, p. 61.

- Brisac 1994, p. 84.

- Arnold 1913, Chapter XIII.

- Brisac 1994, p. 105.

- Arnold 1913, Chapter XV.

- Brisac 1994, p. 120.

- McNamara 2017, p. 222.

- Arnold 1913, Chapter VI.

- Brisac 1994, p. 182.

- Brisac 1994, p. 185.

- de Finance 2012, p. 46–47.

- Brisac 1994, p. 83-84.

- Brisac 1994, p. 83–84.

- Brisac 1994, p. 184–85.

- Tracery at the Encyclopædia Britannica

Bibliography

- Arnold, Hugh (1913). Stained Glass of the Middle Ages in England and France. London: Adam and Charles Black.

- Balcon, Sylvie; Philippot, Jacques (2001). La cathédrale Saint-Pierre-et-Saint-Paul de Troyes. Paris: Centre des monuments nationaux, Monum (Éditions du Patrimoine). ISBN 978-2-85822-615-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brisac, Catherine (1994). Le Vitrail (in French). Paris: La Martinière. ISBN 2-73-242117-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chastel, Robert (2000). L'Art Français- Pré-Moyen Âge- Moyen Âge (in French). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-012298-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Day, Lewis (1897). Windows- a book about Stained and Painted Glass. London: B.T. Brastford.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ducher, Robert (1988). Caractéristique des Styles (in French). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-011539-1.

- de Finance, Laurence (2012). La Sainte-Chapelle - Palais de la Cité (in French). Paris: Éditions du patrimoine, Centre des monuments nationaux. ISBN 978-2-7577-0246-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Houvet, Etienne (2019). Chartres - Guide of the Cathedral. Chartres. ISBN 978-2-909575-65-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martindale, Andrew (1967). Gothic Art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 2-87811-058-7.

- McNamara, Denis (2017). Comprendre L'Art des Églises (in French). Larousse. ISBN 978-2-03-589952-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mignon, Olivier (2015). Architecture des Cathédrales Gothiques (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-6535-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mignon, Olivier (2017). Architecture du Patrimoine Française - Abbayes, Églises, Cathédrales et Châteaux (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-27373-7611-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.

- Wenzler, Claude (2018). Cathédales Cothiques - un Défi Médiéval (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-7712-9.

- Le Guide du Patrimoine en France (in French). Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux. 2002. ISBN 978-2-85822-760-0.